Business

Cut corporate income taxes massively to increase growth, prosperity

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

Business groups are justifiably opposed to the federal government’s June 25 increase of the inclusion rate for capital gains tax. But there is another corporate income tax increase looming. It will come in the form of a 2018 corporate tax reduction that is set to expire starting this year. Ottawa ironically intended it to make Canada more competitive amid the 2018 tax reform and cut in the United States.

According to a study by Trevor Tombe at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, Canada’s corporate income tax rate on new investments will jump from 13.7 percent to 17 percent by 2027. Even worse, for Canada’s high-value-added manufacturing sector, taxation will triple. Higher corporate income taxes, in a nation experiencing difficulties in encouraging domestic or foreign investment in new plant equipment, will struggle to reverse meagre productivity growth—a problem noted by the Bank of Canada.

Heavier taxation will hinder future improvement in incomes and the standard of living, making it a serious issue. Increasing income tax on businesses and investment will not increase prosperity and personal income. The legislation to make the 2018 provisions permanent is, alarmingly, not urgent to politicians.

At least one policy could make Canada more attractive to business, investors, and hard-pressed ordinary citizens. It would be to slash corporate income taxes substantially. Another is to make paying taxes easier, as Magna Corporation founder Frank Stronach suggested. It may surprise some Canadians, but Ottawa’s take from corporate income taxes is a relatively small. However, it is a fast-rising proportion of federal overall revenue: 21 percent in fiscal 2022–23, according to the government, up from 13 percent in fiscal 2000–21, notes the OECD.

Letting companies pay taxes and reducing the tax burden on ordinary people might seem OK to some. However, what happens is that every corporate expense, including taxes, reduces cash flow that reaches individuals. The money remaining in the hands of businesses could either be reinvested or paid out as dividends to owners. Let’s remember that owners are founding families, pension fund beneficiaries (employees, citizens), and ordinary individuals.

As there are fewer available funds, there will be a reduced capacity for capital investment. Investment is required to replace existing equipment, or add new equipment, devices, software, and vehicles for businesses. It only keeps companies competitive and makes employees more productive. This, in turn, makes the whole economy more profitable, thereby increasing taxes paid to governments.

As for the questionable reason for the tax increase, aiming to generate more revenue, recent experience in the United States is informative. The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act reduced corporate income tax from 39 percent of pre-tax income to 21 percent. It resulted in U.S. federal corporate income tax revenue rising 25 percent from 2017 to 2021. Capital investment rose dramatically too, by 20 percent, a key goal of many Canadian policymakers.

Until recently, the Republic of Ireland had a corporate income tax rate of 12.5 percent, a key selling point in its successful efforts to attract foreign investment over the past several decades. Ireland, with few natural resources, is one of the richest and fastest-growing of the OECD nations, despite a bad real estate crash 15 years ago. Near the lowest in the OECD in tax burden, it nevertheless has a high quality of life and services.

If anything, Canada should cut corporate income taxes to below the levels of its main trading partners and rivals. To do so, it will have to extricate itself from the ill-conceived international treaty that compels signatory nations and territories to have a floor rate of at least 15 percent of pre-tax income. Ottawa seems enamoured of multinational agreements and organizations, so it may be highly reluctant to abrogate membership in this growth-dampening arrangement. The statutory federal corporate income tax rate in Canada is 15 percent, but all provincial governments impose their own levies on top of that, ranging from 8 percent in Alberta to 16 percent in Prince Edward Island.

By cutting taxes, we can pave the way for a brighter economic future, marked by increased productivity and the prosperity we all yearn for. This move will also ensure our international competitiveness, a goal we are currently struggling to achieve with our current 25 percent rate (OECD). Canada has a hard time attracting investors. Raising taxes will neither attract more of them nor encourage more investment from existing Canada-domiciled entrepreneurs and companies.

Ian Madsen is senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Business

The world is no longer buying a transition to “something else” without defining what that is

From Resource Works

Even Bill Gates has shifted his stance, acknowledging that renewables alone can’t sustain a modern energy system — a reality still driving decisions in Canada.

You know the world has shifted when the New York Times, long a pulpit for hydrocarbon shame, starts publishing passages like this:

“Changes in policy matter, but the shift is also guided by the practical lessons that companies, governments and societies have learned about the difficulties in shifting from a world that runs on fossil fuels to something else.”

For years, the Times and much of the English-language press clung to a comfortable catechism: 100 per cent renewables were just around the corner, the end of hydrocarbons was preordained, and anyone who pointed to physics or economics was treated as some combination of backward, compromised or dangerous. But now the evidence has grown too big to ignore.

Across Europe, the retreat to energy realism is unmistakable. TotalEnergies is spending €5.1 billion on gas-fired plants in Britain, Italy, France, Ireland and the Netherlands because wind and solar can’t meet demand on their own. Shell is walking away from marquee offshore wind projects because the economics do not work. Italy and Greece are fast-tracking new gas development after years of prohibitions. Europe is rediscovering what modern economies require: firm, dispatchable power and secure domestic supply.

Meanwhile, Canada continues to tell itself a different story — and British Columbia most of all.

A new Fraser Institute study from Jock Finlayson and Karen Graham uses Statistics Canada’s own environmental goods and services and clean-tech accounts to quantify what Canada’s “clean economy” actually is, not what political speeches claim it could be.

The numbers are clear:

- The clean economy is 3.0–3.6 per cent of GDP.

- It accounts for about 2 per cent of employment.

- It has grown, but not faster than the economy overall.

- And its two largest components are hydroelectricity and waste management — mature legacy sectors, not shiny new clean-tech champions.

Despite $158 billion in federal “green” spending since 2014, Canada’s clean economy has not become the unstoppable engine of prosperity that policymakers have promised. Finlayson and Graham’s analysis casts serious doubt on the explosive-growth scenarios embraced by many politicians and commentators.

What’s striking is how mainstream this realism has become. Even Bill Gates, whose philanthropic footprint helped popularize much of the early clean-tech optimism, now says bluntly that the world had “no chance” of hitting its climate targets on the backs of renewables alone. His message is simple: the system is too big, the physics too hard, and the intermittency problem too unforgiving. Wind and solar will grow, but without firm power — nuclear, natural gas with carbon management, next-generation grid technologies — the transition collapses under its own weight. When the world’s most influential climate philanthropist says the story we’ve been sold isn’t technically possible, it should give policymakers pause.

And this is where the British Columbia story becomes astonishing.

It would be one thing if the result was dramatic reductions in emissions. The provincial government remains locked into the CleanBC architecture despite a record of consistently missed targets.

Since the staunchest defenders of CleanBC are not much bothered by the lack of meaningful GHG reductions, a reasonable person is left wondering whether there is some other motivation. Meanwhile, Victoria’s own numbers a couple of years ago projected an annual GDP hit of courtesy CleanBC of roughly $11 billion.

But here is the part that would make any objective analyst blink: when I recently flagged my interest in presenting my research to the CleanBC review panel, I discovered that the “reviewers” were, in fact, two of the key architects of the very program being reviewed. They were effectively asked to judge their own work.

You can imagine what they told us.

What I saw in that room was not an evidence-driven assessment of performance. It was a high-handed, fact-light defence of an ideological commitment. When we presented data showing that doctrinaire renewables-only thinking was failing both the economy and the environment, the reception was dismissive and incurious. It was the opposite of what a serious policy review looks like.

Meanwhile our hydro-based electricity system is facing historic challenges: long term droughts, soaring demand, unanswered questions about how growth will be powered especially in the crucial Northwest BC region, and continuing insistence that providers of reliable and relatively clean natural gas are to be frustrated at every turn.

Elsewhere, the price of change increasingly includes being able to explain how you were going to accomplish the things that you promise.

And yes — in some places it will take time for the tide of energy unreality to recede. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be improving our systems, reducing emissions, and investing in technologies that genuinely work. It simply means we must stop pretending politics can overrule physics.

Europe has learned this lesson the hard way. Global energy companies are reorganizing around a 50-50 world of firm natural gas and renewables — the model many experts have been signalling for years. Even the New York Times now describes this shift with a note of astonishment.

British Columbia, meanwhile, remains committed to its own storyline even as the ground shifts beneath it. This isn’t about who wins the argument — it’s about government staying locked on its most basic duty: safeguarding the incomes and stability of the families who depend on a functioning energy system.

Resource Works News

Business

High-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City a costly boondoggle for Canadian taxpayers

“It’s a good a bet that high-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City isn’t even among the top 1,000 priorities for most Canadians.”

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation is criticizing Prime Minister Mark Carney for borrowing billions more for high-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City.

“Canadians need help paying for basics, they don’t need another massive bill from the government for a project that only benefits one corner of the country,” said Franco Terrazzano, CTF Federal Director. “It’s a good a bet that high-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City isn’t even among the top 1,000 priorities for most Canadians.

“High-speed rail will be another costly taxpayer boondoggle.”

The federal government announced today that the first portion of the high-speed rail line will be built between Ottawa and Montreal with constructing starting in 2029. The entire high-speed rail line is expected to go between Toronto and Quebec City.

The federal Crown corporation tasked with overseeing the project “estimated that the full line will cost between $60 billion and $90 billion, which would be funded by a mix of government money and private investment,” the Globe and Mail reported.

The government already owns a railway company, VIA Rail. The government gave VIA Rail $1.9 billion over the last five years to cover its operating losses, according to the Crown corporation’s annual report.

The federal government is borrowing about $78 billion this year. The federal debt will reach $1.35 trillion by the end of this year. Debt interest charges will cost taxpayers $55.6 billion this year, which is more than the federal government will send to the provinces in health transfers ($54.7 billion) or collect through the GST ($54.4 billion).

“The government is up to its eyeballs in debt and is already spending hundreds of millions of dollars bailing out its current train company, the last thing taxpayers need is to pay higher debt interest charges for a new government train boondoggle,” Terrazzano said. “Instead of borrowing billions more for pet projects, Carney needs to focus on making life more affordable and paying down the debt.”

-

Business2 days ago

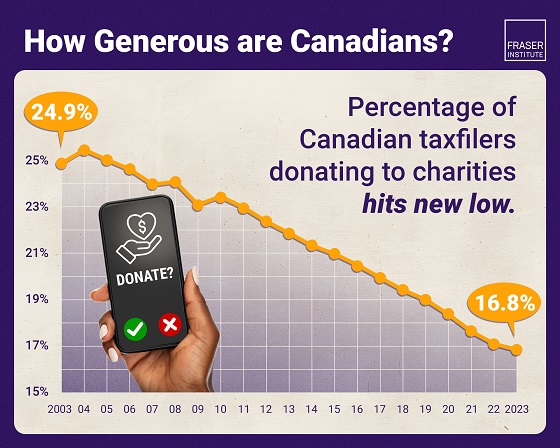

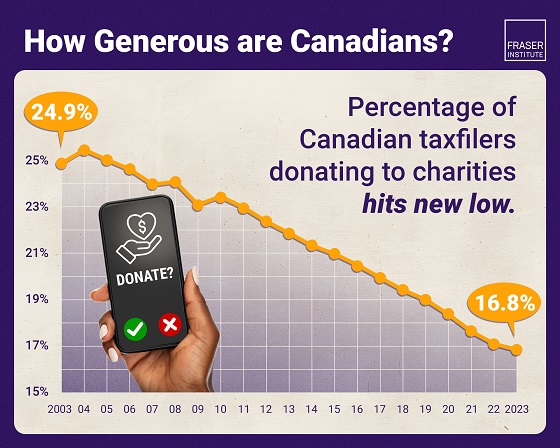

Business2 days agoAlbertans give most on average but Canadian generosity hits lowest point in 20 years

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoOttawa’s New Hate Law Goes Too Far

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoCarney Hears A Who: Here Comes The Grinch

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTaxpayers Federation calls on politicians to reject funding for new Ottawa Senators arena

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoClaims about ‘unmarked graves’ don’t withstand scrutiny

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoMeet REEF — the massive new export engine Canadians have never heard of

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoCanada’s free speech record is cracking under pressure

-

Digital ID1 day ago

Digital ID1 day agoCanada considers creating national ID system using digital passports for domestic use