Opinion

Conversation with Jordy Smith, about Wards and Gasoline Alley?

From: Jordy Smith

To: gjmarks

Sent: Mon, 09 Oct 2017 14:02:40 -0600 (MDT)

Subject: Re: Missed opportunities and possibles?

Thanks for the thoughts, Garfield:

I’ve been observing and studying to find out what Red Deer needs to do if we are to retain residences and businesses from moving to Gasoline Alley. The main thing I keep on finding is how we need to make our city into a more appealing destination in and of itself. Making the Hazlett Lake area into a district with amenities, shopping, etc, is a fantastic idea and one we should go with.

One thing I noticed regarding the conversation of how to keep businesses from moving to Gasoline Alley is how little of an advantage Red Deer has over it. Think about it, many candidates have said that businesses will come to Red Deer because we are in a prime location between Edmonton and Calgary… but so is Gasoline Alley. Some say we will attract more businesses because we have an airport (which is county owned), or because we may be getting a University, but Gasoline Alley can take advantage of these opportunities as well. The only advantage Red Deer has is through developing more high density destination locations like Hazlett Lake.

What are your thoughts on our ‘advantages’ over Gasoline Alley?

Thanks, Garfield:

As you may know, I am in favour of ward system. I have already written extensively on the subject. Here I will include the short Facebook article I wrote entitled, “A Case for Wards.”

When you hear the word ‘wards’ what do you think? Some people picture prison wards, some think of hospital wards, and many don’t know what to think. In this context, wards are districts city councilors represent at City Hall. Places such as Calgary and Edmonton have 12-14 wards, while other locations such as Red Deer and Lethbridge have none. In the latter examples, these cities have at-large elections where everybody votes for multiple candidates according to the number of seats available. (For example, Red Deer has eight council seats, so each voter selects a maximum of eight people.) Red Deer has always used this at-large system for elections, but I advocate for switching to a ward system.

Wards provide direct representation within the city council. They allow anyone who sees an issue in the city to go to their particular councilor and voice their concern. In this situation, the councilor ensures the person’s, and their district’s, voice is heard. If they don’t represent their community well, their constituents can vote for a new councilor in the next election. In our current system, a person can reach out to some or all of Red Deer’s councilors, but if the issue isn’t prevalent across the entire city, it is unlikely to enter the council meeting. Important neighbourhood issues may take a backseat to other matters in distant parts of the city. This scenario isn’t always a problem in at-large systems, but it often favours certain parts of a city more than others. This issue is especially true when a majority of councillors all live in a similar part of the city. In Red Deer, seven of our eight councillors live on the South-East side of the river; in fact, many of our past councils have had disproportionate representation from the South-East side. A ward system gives each part of Red Deer direct representation and a voice in council decisions.

A ward system facilitates a simplified election process for citizens. We have 29 people running for city council; this is the second highest number of candidates the city has ever had (the most was the 2013 election with 30 candidates). Having 29 candidates means every citizen must research and understand the positions of 29 different people to make an informed decision. The sheer amount of options encourages voters to pick people they know, names they recognize, or randomly selected candidates. These reasons for voting aren’t good for our democratic process because they put popularity ahead of platforms and solutions. In comparison, citizens of Calgary only have to consider, at most, nine councillor candidates; Edmontonians only need to research, at the most, 13. Each Red Deer citizen needs to be aware of over twice as many candidates than the two largest cities in Alberta! Wards simplify the election process for citizens, ensuring the most qualified candidates are selected based on the issues and solutions they bring.

Lastly, wards help prevent underqualified candidates with certain advantages to win elections. It takes a strong campaign for candidates to run successfully, and the at-large system makes it more challenging. In a ward system, every candidate only campaigns within their district; this contrasts an at-large system where a candidate must reach the entire city. The at-large system gives two types of candidates an advantage: incumbents, and those with financial resources. Incumbents are current councilors who are running for another term; their advantage comes from successfully running in previous elections. They already have signs, name recognition, more opportunities to talk with the press, and strong networking connections. None of these are bad, but it makes it difficult for new candidates with great ideas to win against incumbents who have already been on council for two, three, or four terms. Candidates with financial resources also have an advantage; they can mobilize and advertise their campaign to the entire city in a short period. Contrast this with other potentially great candidates who don’t have the resources to bring their message to a city of 100,000. Now, the best financial support comes from interest groups; often they have a particular agenda, so they back the candidate who helps them achieve it. This situation is problematic because it allows candidates to be elected whose interests are tied to their financiers, rather than the city. A candidate who lacks these advantages is unlikely to win, even if they are the best person for the position. Wards make it easier for candidates to run; they don’t require as many resources because they only compete in their ward. The incumbents still have some advantage, but the smaller community creates a more even competition.

Some argue Red Deer is too small to have wards, but cities such as Brandon, Manitoba, and other smaller cities in Ontario have had wards for decades. Others believe ward systems make city council more divisive and less focused on the city as a whole. Red Deer can resolve this concern by adopting a three or four-ward system, each with multiple councillors. This idea gives each ward more representation on the council, and encourages councillors to consider more than just one-eighth of the city when making decisions.

Every city begins with an at-large system. With it, Red Deer has grown to its current size. Our councillors work well with each other, making the city a better place. But Red Deer is facing new challenges, and developing wards is a part of overcoming them.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Censorship Industrial Complex

Frances Widdowson’s Arrest Should Alarm Every Canadian

Speech Crimes on Campus

Frances Widdowson, a former colleague professor at Mount Royal University, was arrested this past week on the University of Victoria campus. Her offence? Walking, conversing, and asking questions on a university campus. She was not carrying a megaphone, making threats, organizing a protest, or waving foreign flags. She was planning quietly to discuss, with whoever wished it, a widespread claim that has curiously evaded forensic scrutiny in Canada for five years: that the remains of 215 Indigenous children lie beneath the grounds of the former Kamloops Residential School.

UVic Campus security did not treat her as a scholar. Nor even as a citizen. They treated her as a contaminating source.

The director of security, a woman more reminiscent of a diversity consultant than a peace officer, almost shaking, presented Widdowson with papers and told her to vacate “the property.” When Widdowson questioned the order, citing her Charter rights and the university’s public nature, she was told to leave. She refused, and she was arrested. No force, no defiance, only a refusal to concede that inquiry is trespass.

Widdowson is no provocateur in the modern sense. She is not a shock-jock in a cardigan. She is a once-tenured academic with a long record of challenging orthodoxies in Indigenous policy, identity politics, and campus culture.

In 2008, she co-authored Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry, a book that deconstructed the bureaucratic machinery that profits from preserving Indigenous dependency. The book was methodical, sourced, and daring enough to be labelled heretical in some quarters, but simultaneously boringly Marxist materialistic.

Her arguments have made people uncomfortable for a long time. When I assigned her book to my political science students in the Department of Policy Studies, where Frances also taught, I was summoned by the department head’s office. Someone in my class complained about the book, though I ignored what was said, and the technocratic colleague, as chair of the department, had prepared a host of arguments to chastise me for assigning the book.

Widdowson was good enough to be hired as a colleague of that department, but they were all afraid of her ideas, and perhaps her manner. I have often wondered if the folks in the Mount Royal hiring committee had bothered to read her book. Hey, they had a female Marxist applying for a teaching job. Knowing how they operate makes me think they made giant assumptions about Frances.

My bureaucratic colleague relented. I got the impression that the department head was putting on a show, going through motions he didn’t want to engage in, but which he had to perform for administrative purposes. He had to act on the complaint, though the complaint had no substance. He tried to tell me that the ideas in the book might offend some students, and then went on with the typical dribble about being caring, but agreed that protecting feelings was not the objective of an education, nor the job of a professor.

Haultain’s Substack is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Try it out.

I went to my campus office after the conversation with the department head, typed up a memo detailing our discussion, and emailed it to him to ensure there was a record of my viewpoint. The email got no response. He never mentioned it again, and to this day, 15 or 16 years later, we still haven’t spoken about it.

Some academic arguments are meant to shake things up. That is the purpose of scholarship: to stir the sediment of consensus. To challenge conventional views. Marxist or no, scholars are supposed to push the envelope. Expand the boundaries of our understanding. But in today’s academic culture, discomfort is treated as injury and dissent as violence. So, Widdowson was treated as a threat merely by walking and speaking.

Was the university within its legal rights to remove her? Possibly. Universities can invoke property rights, ironically in Cowichan territory, and provincial legislation sometimes grants them a curious status: publicly funded yet selectively private. But the question is not merely legal. It is cultural and constitutional.

The University of Victoria is a publicly funded institution, governed under provincial authority and subsidized by taxpayers. Its grounds, though some claim they are on unceded Indigenous territory, are functionally administered by the Crown. The university is not a monastery. While it is not a temple to be kept free of doubt, it is not a temple to be torched either. It is a civic institution. An institution of higher learning. When it uses its resources to shield ideology and expel dissenters, it forfeits its academic character.

Consider the contrast. On this same campus, as on many others across the country, protests have called for the destruction of Israel and the extermination of Jews. Banners are waved, slogans chanted, and genocidal euphemisms like “from the river to the sea” are uttered without hesitation. These demonstrations, some of which praise Hamas or glorify martyrdom, proceed unimpeded. Security stands down. The administration issues boilerplate statements about inclusion and respect.

But when a female academic arrives to ask whether the number “215” refers to actual remains or mere radar anomalies, she is marched off by police. The imbalance is not accidental. It is a product of institutional capture.

Contemporary universities have adopted a new moral vocabulary. Terms like “safety,” “inclusion,” and “harm” are now treated as constitutional categories. But their terms are undefined, fluid, shaped by ideology rather than principle. “Safety” no longer refers to bodily security, but has become an emotional preference. “Inclusion” does not mean openness to different ideas and people, but a validation of specific identities. “Harm” is not an act, but a feeling.

Under this logic, Widdowson’s presence becomes a form of injury. Her questions are recast as wounds. And because feelings have been elevated to rights, her removal becomes a public good.

This ideology has structure. It is not random. It rests on a model of revolutionary politics in which dissent must not be part of the conversation. A differing opinion is an obstacle to be cleared. The new inclusivity has become a form of exclusion. It uses the language of welcome to police belief, and the rhetoric of tolerance to enforce conformity.

Charter rights were once the guardrails of public life. They are not supposed to vanish down the rabbit holes when one steps onto that university lawn. The right to free expression, to peaceful assembly, and to enter public space are not conditional on popularity. They are not subject to the feelings of a security director or the preferences of a DEI office.

Widdowson is testing this principle. She did not resist arrest, nor did she make a spectacle of herself. She acted as a citizen asserting a constitutional right. The courts may eventually rule on whether her rights were infringed. But the deeper issue is already visible.

If our public institutions can exile peaceful critics while accommodating radical political agitators who cheer for foreign terror movements, we are not in a neutral society. We are in an elite-managed consensus.

This consensus is enforced by policy. It does not need debate. The consensus managers already know what is true and treat challenges as threats. In this environment, universities are no longer places where young minds wrestle with the pangs of uncertainty. They are enforcing temples of doctrine. Their priests wear lanyards. Their rituals involve land acknowledgments. Their blasphemies include asking inconvenient questions about graves that no one has bothered to exhume.

Frances Widdowson may not be universally admired. No one is. Her conclusions are sharp. Her manner is uncompromising. But that is precisely why her treatment should alarm us. The test of a free society is not how it treats the agreeable, but how it tolerates the disagreeable, to paraphrase Bernard Crick.

When universities lose the confidence to host dissent, they cease to be universities in any meaningful sense. They become echo chambers with fancy libraries. They educate students in the same way a treadmill provides runners with travel: motion without movement.

We are at a moment of reckoning for universities and for Canadian liberal democracy. When citizens cannot openly raise questions without fear of removal, the Charter becomes ornamental. If the test of allowable speech is whether it affirms prevailing narrative and myths, then neither truth nor inquiry has a place among us.

Widdowson’s arrest is not an isolated event. It is a signal that tells us who is welcome in the public square and who is not. It tells us that the basic right to question popular opinions is now conditional. And it affirms for us what we already know: that the guardians of inclusion are, in practice, the agents of exclusion.

No democracy can afford such arbiters. Certainly not one that still calls itself liberal.

Haultain’s Substack is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Try it out.

Energy

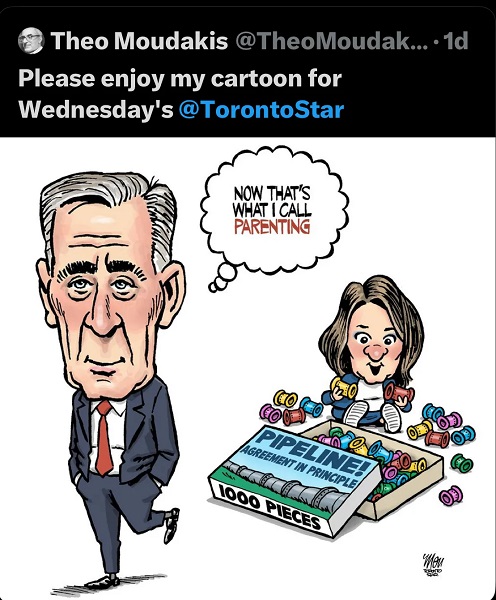

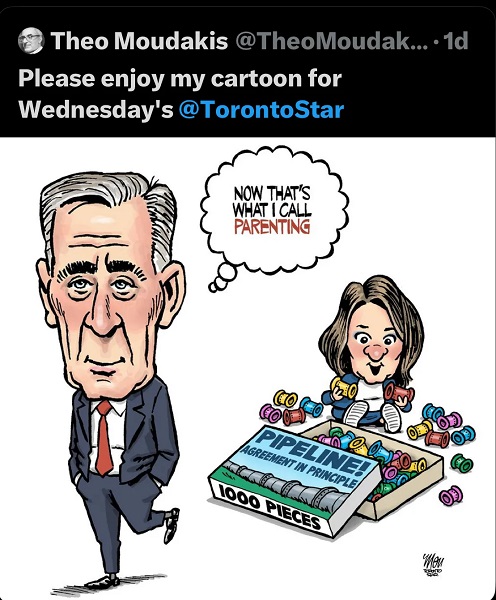

The Trickster Politics of the Tanker Ban are Hiding a Much Bigger Reckoning for B.C.

From Energy Now

By Stewart Muir

For years, a conservation NGO supported by major foreign foundations has taken on the guise of Indigenous governance authority on British Columbia’s north coast. Meanwhile, rights-holding First Nations with an economic agenda are reshaping the region, yet their equal weight is overlooked. A clash of values has resulted.

For more than a decade, British Columbians have been told — mostly by well-meaning journalists and various pressure groups — that an organization called Coastal First Nations speaks with authority for the entire coast. The name sounds official. It sounds governmental. It sounds like a coalition of Indigenous governments with jurisdiction over marine waters.

It isn’t any of those things.

Coastal First Nations (CFN) is a non-governmental organization, incorporated under the BC Societies Act as The Great Bear Initiative Society. It doesn’t hold Indigenous rights or title. It has no legislated role to provide benefits or services to First Nations members. It has no jurisdiction over shipping, marine safety, forestry, fisheries, energy development, or environmental regulation. Yet its statements are frequently treated as if they carry the weight of sovereign authority.

It’s time to say out loud what many leaders — municipal, Indigenous, and industry — already know: CFN is an advocacy group, not a government. Case in point, a recent news story with the following lede: “B.C.’s Coastal First Nations say they will use ‘every tool in their toolbox’ to keep oil tankers out of the northern coastal waters.” A spokesperson claimed to represent “the Rights and Title Holders of the Central and North Coast and Haida Gwaii,” yet notwithstanding the rights of any individual First Nation, CFN does not hold any formal authority.

Here’s why this matters. The truth is, Alberta has already struck its grand bargain with the rest of Canada. Now it’s time to confront the uncomfortable truth that the country is still one bargain short of a functioning national deal.

In 2026, with Canadians increasingly alert to who is shaping national conversations, there is a reasonable expectation that debates affecting our economic future should be led and conducted by Canadians — not by foreign foundations, not by out-of-country campaign strategists, and not by NGOs built to advance someone else’s policy objectives.

Where the confusion came from

CFN’s rise in public visibility traces back to the “Great Bear Rainforest” era, when U.S. philanthropic foundations poured large sums of money into environmental campaigns in British Columbia. A Senate of Canada committee document notes that the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation alone provided approximately $25 million directly to Coastal First Nations, delivered as twenty-five nearly $1 million installments.

CFN also played a central role in the Great Bear Rainforest negotiations, which were financed by a coalition of foreign philanthropies including the Packard Foundation, Hewlett Foundation, Wilburforce Foundation, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Nature Conservancy/Nature United, and Tides Canada Foundation. These foundations collectively contributed tens of millions of dollars to the “conservation financing” model that anchored CFN’s operating environment.

This history isn’t speculative. It’s well documented in foundation reports, Canadian Parliamentary evidence, and the publicly disclosed financial architecture behind the Great Bear Rainforest. For a generation, well-funded U.S. environmental campaigns have worked to make Canadians afraid of their own shadow by seeding doubt, stoking paralysis, and teaching a resource nation to second-guess the very wealth that built it.

Between 2010 and 2018, an independent forensic accounting review by Deloitte Forensic (backed by the Alberta government) found that foreign foundations provided roughly $788.1 million in grants for Canadian environmental initiatives. The largest single category — by a wide margin — was marine-based initiatives, totalling $297.2 million. In Deloitte’s categorization, “marine-based” overwhelmingly refers to coastal campaigns: Great Bear Rainforest–related advocacy, anti-tanker/shipping activism, marine-use regulation campaigns, marine ecological programs, and other coastal political work.

Land-based initiatives were the second-largest category ($191 million), followed by wildlife preservation ($173 million).

The forensic review also showed that of the $427.2 million that physically entered Canada, 82% — approximately $350.3 million — was spent in British Columbia, with the dominant share directed specifically toward coastal and marine initiatives.

Taken together, these findings confirm that foreign-funded environmental activity in Canada has been geographically concentrated in British Columbia and thematically concentrated on the coast – exactly the domain where CFN has been positioned as a public-facing authority.

The real authority lies with the nations themselves

If British Columbians want to understand who truly governs the coast, they should look to the Indigenous governments that hold rights, title, citizens, and accountability — not NGOs that comment from the sidelines. That means not overlooking:

- Haisla Nation, leaders of Cedar LNG

- Nisga’a Nation, co-developers of Ksi Lisims LNG

- Gitxaala Nation, asserting legal and territorial authority

- Kitselas and Kitsumkalum, both shaping regional development

These governments are also coastal First Nations. They negotiate major economic partnerships, steward lands and waters, and make decisions grounded in their own legal orders. Moreover, representation is the key measure of accountability in a democracy: First Nations governing councils are elected by their members. The CFN is not elected. The nations are accountable to their own people — not to U.S. philanthropies or to the strategic objectives of foreign-backed environmental campaigns.

The Haisla Nation once belonged to CFN, but quit in protest in 2012 when the body opposed LNG. The Haisla council went on to fully embrace economic development via liquefied natural gas and own the upcoming Cedar LNG project.

Meanwhile, the central and northern coastal regions where CFN has opposed numerous economic opportunities continue to suffer the worst child poverty in British Columbia.

In the delicate politics of the region’s First Nations alliances, relationships are constantly in motion and governed by inviolable traditions of mutual respect. From these threads, it has to be said that the CFN’s strategy of weaving the appearance of unanimity is truly a fabrication. In point of fact, CFN represents just one half of the story. My data source tells the story, by drawing together the latest available economic and demographic information for 216 British Columbia First Nations:

- Status Indian residents of CFN communities on the north coast number 5,484, with a total membership near and far of 20,447.

- The pro-development group noted earlier numbers 5,505 living local out of a total membership of 16,830.

In other words, virtually equal. Hence it’s obvious that any media report citing CFN as the singular authority for local First Nations interests is a misleading one. CFN speaks for only a slice of the North Coast, not the whole, and the numbers make that impossible to ignore.

When a CFN motion opposing responsible resource development was adopted by the Assembly of First Nations (see Dec. 2 news), it was further evidence that the deck is stacked against First Nations that are accountable and position themselves as having broad responsibilities, including but not limited to raising the standard of living of their members.

The future belongs to the nations

The politics of LNG on the North Coast can’t be grasped without staring directly at the tanker ban — not as scripture, but as the political curiosity it has become. Anyone who knows these waters understands it’s mostly theatre: it doesn’t question letting Alaska oil tanker ships transit our exclusive economic zone when we cannot, and it doesn’t touch the real risks coastal people actually worry about. Yet waving it away is naïve. The ban behaves like a trickster spirit in our public life — capricious, emotionally loaded, and capable of turning a routine policy debate into a cultural conflagration with barely a flick of its tail.

This is why Coastal First Nations retain such gravitational pull. For years, the ban has served as the moral architecture of their Great Bear Sea campaign. CFN represents a long-game strategy — build legitimacy, occupy the moral high ground, and shape the destiny of a nation by holding the symbolic centre. Their concerns seem genuine and rooted in lived stewardship – yet were shaped by Madison Avenue minds hired by American philanthropists to affect our politics. But a near equal number of coastal nation residents unified by a different outlook also have skin in the game. They are charting futures grounded in prosperity, environmental care, and sovereignty on their own terms, and their authority is the real thing — born of title, law, and accountability to their own people.

And here is the irony worth heeding: the tanker ban’s pageantry masks a solution. It is dragging into daylight a conversation the province has avoided for decades — a conversation that will soon prove inevitable as court rulings unsettle the very foundation of property rights in British Columbia. This is the hinge that the moment turns on.

Canada cannot resolve its growing national contradictions without moving its energy to global markets. Alberta has already made its grand bargain with the country. Now British Columbia must craft its own — harnessing the prosperity of energy development to discharge political debts and finally settle the title question that has defined the province’s modern era.

Stewart Muir

-

National12 hours ago

National12 hours agoMedia bound to pay the price for selling their freedom to (selectively) offend

-

Bruce Dowbiggin11 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin11 hours agoSometimes An Ingrate Nation Pt. 2: The Great One Makes His Choice

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoUniversity of Colorado will pay $10 million to staff, students for trying to force them to take COVID shots

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOil tanker traffic surges but spills stay at zero after Trans Mountain Expansion

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoAlberta will use provincial laws to stop Canadian gov’t from trying to confiscate legal firearms

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoELZABETH MAY HAS IT WRONG: An Alberta to Prince Rupert Oil Pipeline Will Contribute to Greater Global Oil Tanker Safety

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoJustice Centre campaigning Canadian provinces to follow Alberta’s lead protecting professionals

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoCanadian legislator introduces bill to establish ‘Freedom Convoy Recognition Day’ as a holiday