Business

Carbon tariff proposal carries risks and consequences for Canada

A carbon tariff—a policy that would impose fees on imported goods based on their carbon emissions—is built on the idea that Canada should penalize foreign producers for not adhering to stringent climate policies. While this may sound like a strong stance on climate action, the reality is that such a policy carries major risks for Canada’s economy. As a resource-rich nation that exports carbon-intensive products like oil, natural gas, and minerals, Canada stands to lose more than it gains from this approach.

Mark Carney, who is competing for the federal Liberal leadership, has made the introduction of a carbon tariff the number two promise in his 16-point industrial competitiveness strategy.

Key problems with a carbon tariff in Canada

1. Retaliation from other countries

A carbon tariff (also known as a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM) would not go unchallenged by Canada’s trading partners. Major exporters to Canada, such as the United States and China, are unlikely to accept this policy without a response. They could retaliate by imposing tariffs on Canadian goods, making it significantly harder for Canadian businesses to compete in international markets. This could be particularly damaging for key industries like oil and gas, mining, and manufacturing, which rely heavily on exports. A trade war over carbon tariffs could weaken the Canadian economy and lead to job losses across multiple sectors.

2. Canada is an exporting nation

Canada exports far more carbon-intensive goods than it imports. By introducing a carbon tariff on foreign products, Canada is effectively inviting other countries to do the same, targeting Canadian exports with similar carbon-based tariffs. This would make Canadian goods more expensive on the global market, reducing demand for them and harming the very industries that drive Canada’s economy. The result? A weaker economy, job losses, and higher costs for businesses that depend on trade.

3. Big business paying for consumers’ emissions

The Carney plan also proposes to make large businesses bear the cost of helping individual households lower their carbon emissions. While this may sound like a fair approach, in practice, these costs will be passed down to consumers. Businesses will need to offset these additional expenses, leading to higher prices on everyday goods and services. In the end, it is Canadian families who will bear the financial burden, facing increased living costs, higher taxes, and fewer job opportunities as businesses struggle to absorb the additional costs.

CBAM in context: implications for Canada

Has this been tried elsewhere?

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is currently in effect. It entered its transitional phase on October 1, 2023, during which importers of certain carbon-intensive goods are required to report the embedded emissions of their imports without incurring financial liabilities. This phase is set to last until the end of 2025. The definitive regime, where importers will need to purchase CBAM certificates corresponding to the carbon emissions of their imported goods, is scheduled to begin in 2026.

However, Europe is not Canada’s largest trading partner—that is the United States. With Donald Trump back in the presidency, there is no chance that the U.S. will implement a CBAM of its own. If Canada were to move forward with a unilateral carbon tariff, if anyone prepared to argue that it would not face significant economic punishment from the Trump White House?

Moreover, with 91 percent of the world having no carbon tariff, other countries would impose countermeasures, leaving Canadian businesses struggling to remain competitive.

This raises the question: is the push for a carbon tariff in Canada more about political positioning than economic pragmatism? Given the unlikelihood of U.S. participation, a Canadian CBAM would amount to a unilateral economic sacrifice. While this may appeal to certain voter bases, the reality is that such a policy would carry immense risks without global coordination. Policymakers should carefully consider whether pursuing this path makes sense in a world where Canada’s largest trading partner is unlikely to follow suit.

Where do others stand?

Chrystia Freeland, the former finance minister and current Liberal leadership candidate, has not explicitly detailed her stance on carbon tariffs. However, she has emphasized the importance of defending Canadian interests against U.S. economic nationalism, particularly in response to potential tariffs from the U.S.

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre is a vocal critic of carbon pricing mechanisms, including carbon taxes, and has pledged to repeal such measures if elected.

Elizabeth May, leader of the Green Party, has consistently advocated for strong environmental policies, including carbon pricing, but has not specifically addressed carbon tariffs in recent statements.

What it means to consumers

Here are some relatable examples of carbon-intensive exports and imports for the average Canadian:

Carbon-Intensive Exports from Canada

Oil & Gas – Canada is a major exporter of crude oil, natural gas, and refined petroleum products, particularly to the U.S. If a carbon tariff were applied to these products, it could make them more expensive and less competitive in global markets, affecting jobs in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland.

Lumber & Pulp – Canada is a leading exporter of forestry products, including lumber, paper, and pulp, which require significant energy and emissions to produce. If tariffs are imposed on Canadian wood products, the forestry sector could suffer.

Agricultural Products – Fertilizers, beef, and grain production all have significant carbon footprints. If trading partners retaliate with tariffs, Canadian farmers may struggle to compete in global markets.

Carbon-Intensive Imports into Canada

Steel & Aluminum – Canada imports a large amount of steel, primarily from China and the U.S., which is essential for industries like construction, manufacturing, and automotive production. A carbon tariff would drive up costs for these industries.

Consumer Goods from China – Many everyday products (electronics, clothing, appliances) are imported from countries with high-carbon electricity grids. A carbon tariff could increase the price of these goods for Canadian consumers.

Food Products – Imported produce, meats, and packaged foods from countries like the U.S. and Mexico often have high transportation-related emissions. A carbon tariff could increase grocery bills.

Business

Closing information gaps to strengthen Canada’s border security and track fentanyl

By Sean Parker, Dawn Jutla, and Peter Copeland for Inside Policy

To promote better results, we lay out a collaborative approach

Despite exaggerated claims about how much fentanyl is trafficked across the border from Canada to the United States, the reality is that our detection, search, and seizure capacity is extremely limited.

We’re dealing with a “known unknown”: a risk we’re aware of, but don’t yet have the capacity to understand its extent.

What’s more, it may be that the flow of precursor chemicals—ingredients used in the production of fentanyl—is where much of the concern lies. Until we enhance our tracking, search, and seizure capacity, much will remain speculative.

As border security is further scrutinized, and the extent of fentanyl production and trafficking gets brought into sharper focus, the role of the federal government’s Precursor Chemical Risk Management Unit (PCRMU)—announced recently by Health Canada—will become apparent.

Ottawa recently took action to enhance the capabilities of the PCRMU. It says the new unit will “provide better insights into precursor chemicals, distribution channels, and enhanced monitoring and surveillance to enable timely law enforcement action.” The big question is, how will the PCRMU track the precursor drugs entering into Canada that are used to produce fentanyl?

Key players in the import-export ecosystem do not have the right regulatory framework and responsibilities to track and share information, detect suspect activities, and be incentivized to act on it. That’s one of the reasons why we know so little about how much fentanyl is produced and trafficked.

Without proper collaboration with industry, law enforcement, and financial institutions, these tracking efforts are doomed to fail. To promote better results, we lay out a collaborative approach that distributes responsibilities and retools incentives. These measures would enhance information collection capabilities, incentivize system actors to compliance, and better equip law enforcement and border security services for the safety of Canadians.

Trade-off bottleneck: addressing the costs of enhanced screening

To date, it’s been challenging to increase our ability to detect, search, and seize illegal goods trafficked through ports and border crossings. This is due to trade-offs between heightened manual search and seizure efforts at ports of entry, and the economic impacts of these efforts.

In 2024, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) admitted over 93 million travelers. Meanwhile, 5.3 million trucks transported commercial goods into Canada, around 3.6 million shipments arrived via air cargo, nearly 2 million containers were processed at Canadian ports, roughly 1.9 million rail cars carried goods into the country, and about 145.7 million courier shipments crossed the border. The CBSA employs a risk-based approach to border security, utilizing intelligence, behavioral analysis, and random selection to identify individuals or shipments that may warrant additional scrutiny. This triaging process aims to balance effective enforcement with the facilitation of legitimate travel and trade.

Exact percentages of travelers subjected to secondary inspections are not publicly disclosed, but it’s understood that only a small fraction undergo such scrutiny. We don’t learn about the prevalence of these issues through our border screening measures, but in crime reporting data—after it’s too late to avert.

It’s key to have an approach that minimizes time and personnel resources deployed at points of entry. To be effective without being economically disruptive, policymakers, law enforcement, and border security need to strengthen requirements for information gathering, live tracking, and sharing. Legislative and regulatory change to require additional information of buyers and sellers—along with stringent penalties to enforce non-compliance—is a low-cost, logistically efficient way of distributing responsibility for this complex and multifaceted issue. A key concept explored in this paper is strengthening governance controls (“controls”) over fentanyl supply chains through new processes and data digitization, which could aid the PCRMU in their strategic objectives.

Enhanced supply chain controls are needed

When it comes to detailed supply chain knowledge of fentanyl precursor chemicals moving in and out of Canada, regulator knowledge is limited.

That’s why regulatory reform is the backbone of change. It’s necessary to ensure that strategic objectives are met by all accountable stakeholders to protect the supply chain and identify issues. To rectify the issues, solutions can be taken by the PCRMU to obtain and govern a modern fentanyl traceability system/platform (“platform”) that would provide live transparency to regulators.

A fresh set of supply chain controls, integrated into a platform as shown in Fig. 1, could significantly aid the PCRMU in identifying suspicious activities and prioritizing investigations.

Our described system has two distinctive streams: one which leverages a combination of physical controls such as package tampering and altered documentation against a second stream that looks at payment counterparties. Customs agencies, transporters, receivers, and financial institutions would have a hand in ensuring that controls in the platform are working. The platform includes several embedded controls to enhance supply chain oversight. It uses commercially available Vision AI to assess packaging and blockchain cryptography to verify shipment documentation integrity. Shipment weight and quantity are tracked from source to destination to detect diversion, while a four-eyes verification process ensures independent reconciliation by the seller, customs, and receiver. Additionally, payment details are linked to shipments to uncover suspicious financial activity and support investigations by financial institutions and regulators like FINTRAC and FINCEN.

A modern platform securely distributes responsibility in a way that’s cost effective and efficient so as not to overburden any one actor. It also ensures that companies of all sizes can participate, and protects them from exploitation by criminals and reputational damage.

In addition to these technological enhancements and more robust system controls, better collaboration between the key players in the fentanyl supply chain is needed, along with policy changes to incentivize each key fentanyl supply chain stakeholder to adopt the new controls.

Canadian financial institutions: a chance for further scrutiny

Financial institutions (FIs) are usually the first point of contact when a payment is being made by a purchaser to a supplier for precursor chemicals that could be used in the production of fentanyl. It is crucial that they enhance their screening and security processes.

Chemicals may be purchased by wires or via import letters of credit. The latter is the more likely of the two instruments to be used because this ensures that the terms and conditions in the letter of credit are met with proof of shipment prior to payment being released. Payments via wire require less transparency.

Where a buyer pays for precursor chemicals with a wire, it should result in further scrutiny by the financial institution. Requests for supporting documentation including terms and conditions, along with proof of shipment and receipt, should be provided. Under new regulatory policy, buyers would be required to place such supporting documentation on the shared platform.

The less transparent a payment channel is in relation to the supply chain, the more concerning it should be from a risk point of view. Certain payment channels may be leveraged to further mask illicit activity throughout the supply chain. At the onset of the relationship the seller and buyers would link payment information on the platform (payment channel, recipient name, recipient’s bank, date, and payment amount) to each precursor or fentanyl shipment. The supplier, in turn, should record match payment information (payment channel, supplier name, supplier’s bank, date, and payment amount).

Linking payment to physical shipment would enable data analytics to detect irregularities. An irregularity is flagged when the amounts and/or volume of payments far exceed the value of the received goods or vice versa. The system would be able to understand which fentanyl supply chains tend to use a particular set of FIs. This makes it possible to conduct real-time mapping of companies, their fentanyl and precursor shipments and receipts, and the payment institutions they use. With this bigger picture, FIs and law enforcement could connect the dots faster.

Live traceability reporting

Today, suppliers of fentanyl precursors are subject to the Pre-Export Notification Online (PEN Online) database. This database enables governments to monitor international trade in precursor chemicals by sending and receiving pre-export notifications. The system helps prevent the diversion of chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of drugs by allowing authorities to verify the legitimacy of shipments before they occur.

To further strengthen oversight, the platform utilizes immutability technologies—such as blockchain or secure immutable databases—which can be employed to encrypt all shipping documents and securely share them. This presents an auditable form of chain-of-custody and makes any alterations apparent. Customs and buyers would have the capability to verify the authenticity of the originating documents in a way that doesn’t compromise business confidentiality. With the use of these technologies, law enforcement can narrow down their investigations.

An information gap currently exists as the receivers of the shipments don’t share their receipts information with PEN. To strengthen governance on fentanyl supply chains, regulatory policy and legislative changes are needed. The private sector should be mandated to report received quantities of fentanyl or its precursors, as well as suspicious receiving destinations. This could be accomplished on the platform which would embed the receiving process, a reconciliation process of the transaction, the secure upload and sharing of documents, and would be minimally disruptive to business processes.

Additionally, geo-location technology embedded in mobile devices and/or shipments would provide real-time location-based tracking of custody transactions. These geo-controls would ensure accountability across the fentanyl supply chain, in particular where shipments veer off or stop too long on regular shipping routes. Canadian transporters of fentanyl and its precursor chemicals should play an important role in detecting illicit diversion/activities.

Digital labelling

Licensed fentanyl manufacturers could add new unique digital labels to their shipments to get expedited clearance. For example, immutable digital labelling platforms enable tamper-proof digital labels for legitimate fentanyl shipments. This would give pharmacies, doctors, and regulators transparency into the fentanyl’s:

- Chemical composition and concentrations (determining legitimate vs. adulterated versions of the drug)

- Manufacturing facility ID, batch ID, and regulatory compliance status

- Intended buyer authentication (such as licensed pharmaceutical firms or distributors)

Immutable digital labelling platforms offer secure role-based access control. They can display customized data views according to time of day, language, and location. Digital labels could enable international border agencies and law enforcement to receive usable data, allowing legal shipments through faster while triggering closer shipment examinations for those without of a digital label.

International and domestic transporter controls

Transporters act as intermediaries in the supply chain. Their operations could be monitored through a regulatory policy that mandates their participation in the platform for fentanyl and precursor shipments. The platform would support a mobile app interface for participants on-the-move, as well as a web portal and application programming interfaces (APIs) for large-size supply chain participants. Secure scanning of packaging at multiple checkpoints, combined with real-time tracking, would provide an additional layer of protection against fraud, truckers taking bribes, and unauthorized alterations to shipments and documents.

Regulators and law enforcement participation

Technology-based fentanyl controls for suppliers, buyers, and transporters may be reinforced by international customs and law enforcement collaboration on the platform. Both CBSA and law enforcement could log in and view alerts about suspicious activities issued from the FIs, transporters, or receivers. The reporting would allow government personnel to view a breakdown of fentanyl importers, the number of import permit applications, and the amount of fentanyl and its precursors flowing into the country. Responsible regulatory agencies—such as the CBSA and PCRMU—could leverage the reporting to identify hot spots.

The platform would use machine learning to support CBSA personnel in processing an incoming fentanyl or precursor shipment. Machine learning refers to AI algorithms and systems that improve their knowledge with experience. For example, an AI assistant on the traceability system could use machine learning to predict and communicate which import shipments arriving at the border should be passed. It can base these suggestions on criteria like volume, price, origin of raw materials, and origin of material at import point. It can also leverage data from other sources such as buyers, sellers, and banks to make predictions. As an outcome, the shipment may be recommended to pass, flagged as suspicious, or deemed to require an investigation by CBSA.

It’s necessary to keep up to date on new precursor chemicals as the drug is reformulated. Here, Health Canada can play a role, using its new labs and tests—expected as part of the recently announced Canadian Drug Analysis Centre—to provide chemical analysis of seized fentanyl. This would inform which additional chemical supply chains should be tracked in the PCRMU’s collaborative platform, and all stakeholders would widen their scope of review.

These new tools would complement existing cross-border initiatives, including joint U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico crackdowns on illicit drug labs, as well as sovereign efforts. They have the potential to play a vital role in addressing fentanyl trafficking.

A robust, multi-pronged strategy—integrating existing safeguards with a new PCRMU traceability platform—could significantly disrupt the illegal production and distribution of fentanyl. By tracking critical supply chain events and authenticating shipment data, the platform would equip law enforcement and border agencies in Canada, the U.S., and Mexico with timely, actionable intelligence. The human toll demands urgency: from 2017 to 2022, the U.S. averaged 80,000 opioid-related deaths annually, while Canada saw roughly 5,500 per year from 2016 to 2024. In just the first nine months of 2024, Canadian emergency services responded to 28,813 opioid-related overdoses.

Combating this crisis requires more than enforcement. It demands enforceable transparency. Strengthened governance—powered by advanced traceability technology and coordinated public-private collaboration—is essential. This paper outlines key digital controls that can be implemented by global suppliers, Canadian buyers, transporters, customs, and financial institutions. With federal leadership, Canada can spearhead the adoption of proven, homegrown technologies to secure fentanyl supply chains and save lives.

Sean Parker is a compliance leader with well over a decade of experience in financial crime compliance, and a contributor to the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Dawn Jutla is the CEO of Peer Ledger, the maker of a traceability platform that embeds new control processes on supply chains, and a professor at the Sobey School of Business.

Peter Copeland is deputy director of domestic policy at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

2025 Federal Election

Don’t double-down on net zero again

From the Fraser Institute

In the preamble to the Paris Agreement, world leaders loftily declared they would keep temperature rises “well below 2°C” and perhaps even under 1.5°C. That was never on the cards—it would have required the world’s economies to effectively come to a grinding halt.

The truth is that the “net zero” green agenda, based on massive subsidies and expensive legislation, will likely cost more than CAD$38 trillion per year across the century, making it utterly unattractive to voters in almost every nation on Earth.

When President Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement for the first time in 2017, then-Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was quick to claim the moral high ground, declaring that “we will continue to work with our domestic and international partners to drive progress on one of the greatest challenges we face as a world.”

Trudeau has now been swept from the stage. On his first day back in office, President Trump signed an executive order that again begins the formal, twelve-month-long process of withdrawing the United States from the Paris Agreement.

It will be tempting for Canada to step anew into the void left by the United States. But if the goal is to make effective climate policy, whoever is Canada’s prime minister needs to avoid empty virtue signaling. It would be easy for Canada to declare again that it’ll form a “coalition of the willing” with Europe. The truth is that, just like last time, that approach would do next to nothing for the planet.

Climate summits have generated vast amounts of attention and breathless reporting giving the impression that they are crucial to the planet’s survival. Scratch the surface, and the results are far less impressive. In 2021, the world promised to phase-down coal. Since then, global coal consumption has only gone up. Virtually every summit has promised to cut emissions but they’ve increased almost every single year, and 2024 reached a new high.

Way before the Paris Agreement was inked, the Kyoto Protocol was once sold as a key part of the solution to global warming. Yet studies show it achieved virtually nothing for climate change.

In the preamble to the Paris Agreement, world leaders loftily declared they would keep temperature rises “well below 2°C” and perhaps even under 1.5°C. That was never on the cards—it would have required the world’s economies to effectively come to a grinding halt.

The truth is that the “net zero” green agenda, based on massive subsidies and expensive legislation, will likely cost more than CAD$38 trillion per year across the century, making it utterly unattractive to voters in almost every nation on Earth.

The awkward reality is that emissions from Canada, the EU, and other countries pursuing climate policies matter little in the 21st century. Canada likely only makes up about 1.5 per cent of the world’s emissions. Add together Canada’s output with that of every single country of the rich-world OECD, and this only makes up about one-fifth of global emissions this century, using the United Nations’ ‘middle of the road’ forecast. The other four-fifths of emissions come mostly from China, India and Africa.

Even if wealthy countries like Canada impoverish themselves, the result is tiny — run the UN’s standard climate model with and without Canada going net-zero in 2050, and the difference is immeasurable even in 2100. Moreover, much of the production and emissions just move to the Global South—and even less is achieved.

One good example of this is the United Kingdom, which—like Prime Minister Trudeau once did—has leaned into climate policies, suggesting it would lead the efforts for strong climate agreements. British families are paying a heavy price for their government going farther than almost any other in pursuing the climate agenda: just the inflation-adjusted electricity price, weighted across households and industry, has tripled from 2003 to 2023, mostly because of climate policies. This need not have been so: the US electricity price has remained almost unchanged over the same period.

The effect on families is devastating. Had prices stayed at 2003 levels, an average family-of-four would now be spending CAD$3,380 on electricity—which includes indirect industry costs. Instead, it now pays $9,740 per year.

Rising electricity costs make investment less attractive: European businesses pay triple US electricity costs, and nearly two-thirds of European companies say energy prices are now a major impediment to investment.

The Paris Treaty approach is fundamentally flawed. Carbon emissions continue to grow because cheap, reliable power, mostly from fossil fuels, drives economic growth. Wealthy countries like Canada, the US, and European Union members have started to cut emissions—often by shifting production elsewhere—but the rest of the world remains focused on eradicating poverty.

Poor countries will rightly reject making carbon cuts unless there is a huge flow of “climate aid” from rich nations, and want trillions of US dollars per year. That won’t happen. The new US government will not pay, and the other rich countries cannot foot the bill alone.

Without these huge transfers of wealth, China, India and many other developing countries will disavow expensive climate policies, too. This potentially leaves a rag-tag group led by a few Western European progressive nations, which can scarcely afford their own policies and have no ability to pay off everyone else.

When the United States withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2017, Canada’s doubling down on the Paris Treaty sent the signal that it would be worthwhile spending hundreds of trillions of dollars to make no real difference to temperatures. We fool ourselves if we pretend that doing so for a second time will help the planet.

We need to realize that fixing climate change isn’t about sanctimonious summits, lofty speeches, and bluster. In coming weeks I’ll outline the case for efficient policies like innovation, adaptation and prosperity.

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoLiberals Replace Candidate Embroiled in Election Interference Scandal with Board Member of School Flagged in Canada’s Election Interference Inquiry

-

Alberta16 hours ago

Alberta16 hours agoIs Canada’s Federation Fair?

-

Alberta15 hours ago

Alberta15 hours agoProvince introducing “Patient-Focused Funding Model” to fund acute care in Alberta

-

espionage18 hours ago

espionage18 hours agoU.S. Experts Warn Canada Is Losing the Fight Against PRC Criminal Networks—Washington Has Run Out of Patience

-

Alberta11 hours ago

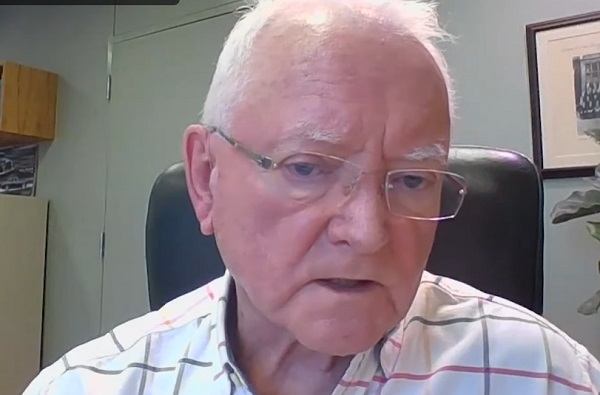

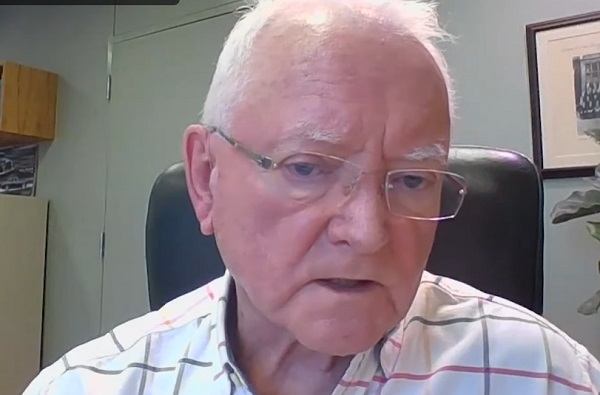

Alberta11 hours agoMedical regulator stops short of revoking license of Alberta doctor skeptic of COVID vaccine

-

Automotive19 hours ago

Automotive19 hours agoTesla Vandals Keep Running Into The Same Problem … Cameras

-

International12 hours ago

International12 hours agoUN committee urges Canada to repeal euthanasia for non-terminally ill patients

-

COVID-195 hours ago

COVID-195 hours agoMassive new study links COVID jabs to higher risk of myocarditis, stroke, artery disease