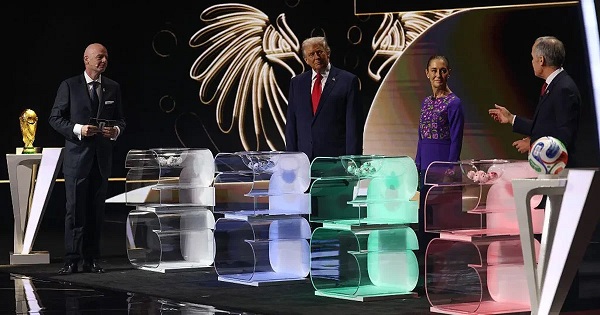

Spectacular fiascos: Canada’s “front end” international reputation has been in decline throughout the Liberals’ nine years in office – thanks to, among other incidents, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s odd sartorial decisions during his 2018 visit to India (top), Canada’s disintegrating military (middle), and the foreign policy establishment’s failure to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2020 (bottom). But what happens in the “back end” – like foreign aid – is equally important. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Sean Kilpatrick; (middle) Canadian Army; (bottom) IAEA Imagebank, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Spectacular fiascos: Canada’s “front end” international reputation has been in decline throughout the Liberals’ nine years in office – thanks to, among other incidents, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s odd sartorial decisions during his 2018 visit to India (top), Canada’s disintegrating military (middle), and the foreign policy establishment’s failure to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2020 (bottom). But what happens in the “back end” – like foreign aid – is equally important. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Sean Kilpatrick; (middle) Canadian Army; (bottom) IAEA Imagebank, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

When foreign affairs do get noticed, typically the front-facing actions of the prime minister, foreign affairs minister or defence minister are scrutinized. And why not, since it’s a target-rich environment, with Canada experiencing some spectacular failures over the Liberals’ nine years in office. In 2020, after an intense and costly push, Canada failed to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council that its foreign policy establishment had long craved. A year later, Canada was left out of AUKUS, a new defence and security pact among the United States, United Kingdom and Australia intended to counter China’s expansionism. Just last month, 23 U.S. senators from both parties issued a letter deeply critical of Canada’s parsimonious defence spending. And then there’s the symbolic damage wrought by Canada’s performative prime minister, such as his cringeworthy decision on a 2018 state visit to India to dress himself and his family in traditional Indian wedding garb.

A largely unexamined though arguably even more important feature of foreign policy, however, is the back end, the foreign assistance administered and funded through Global Affairs Canada. Under the Justin Trudeau government, assistance diplomacy has been transformed – and in ways at least as worrisome and damaging as the more high-profile examples cited above.

The words “development assistance” probably conjure up images of Canadian specialists overseeing the provision of clean water in dirt-poor rural areas, conducting immunizations of vulnerable children, building roads, planning much-needed energy infrastructure in regions that still use dung fires and candle-light, constructing new schools, fighting forest fires, or organizing and staffing colleges that turn out agronomists, foresters, hydrologists, engineers and so on. In other words, doing the things needed to, first, address crises that are killing people and shortening lives, and second, providing poor countries the tools needed to lift themselves out of poverty over the long term.

But if these were ever the priorities, they have been deliberately cast aside. In 2017, then Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland and Minister of International Development Marie-Claude Bibeau produced a 77-page policy document, Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy. The paper is explicitly calibrated to the United Nations-sponsored Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Agenda, a multilateral agreement signed by Canada in 2015, describes itself as “a global blueprint…to achieve gender equality, reach net zero emissions, halt and reverse nature loss, build resilient and inclusive societies and economies, and make sure everyone has access to quality education and health care.”

Sharing whose “values”? Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, unveiled in 2017 by then Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland (left) and Minister of International Development Marie-Claude Bibeau (right), places “the right to access safe and legal abortions” “at the core” of Canada’s foreign policy, accompanied by a $14-billion budget over a 10-year period. (Sources of photos: (left) OEA-OAS, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; (right) The Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld)

Sharing whose “values”? Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, unveiled in 2017 by then Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland (left) and Minister of International Development Marie-Claude Bibeau (right), places “the right to access safe and legal abortions” “at the core” of Canada’s foreign policy, accompanied by a $14-billion budget over a 10-year period. (Sources of photos: (left) OEA-OAS, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; (right) The Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld)

Like the 2030 Agenda, Canada’s Feminist Foreign Policy advocates an “intersectionality” that ties together climate action and feminism. Bibeau described it as a “new vision for international assistance” and proclaimed that Canada should play “a leading international role.” In her preface to the document, Freeland wrote that, “Canadians are safer and more prosperous when more of the world shares our values.” For the average Canadian, the word “values” probably brings to mind things like a commitment to democracy, individual equality, tolerance of minorities and religions, or being left at liberty to pursue a livelihood and build a family. But those are apparently not the most important values of the people who plan and implement Canada’s foreign assistance effort.

Freeland performed a nifty conceptual shuffle by moving from the innocuous statement that “women’s rights are human rights” to an explication that those rights include “sexual and reproductive rights – and the right to access safe and legal abortions,” and then to the pronouncement that, “These rights are at the core of our foreign policy.” In Freeland’s world Canadian “values” – and the values Canada seeks to transmit to other countries – are focused in very particular areas and skew towards a particular end of the ideological spectrum. Whatever your view is on contraception and abortion rights, the idea that sexual and reproductive “health and rights” are top-tier Canadian values, should drive foreign assistance funding and lie at the “core” of the nation’s foreign policy should surely all be matters for serious public scrutiny and debate.

‘Far from deploying Canadian aid workers to African countries to listen, learn and craft policies that promote development in line with local goals and aspirations,’ former ambassador Mulroney says, ‘Canada simply transfers funds to its likeminded partners in multilateral organizations, progressive foundations, and the big abortion providers.’

The money was fairly quick to follow the policy directives flowing from the 2017 paper. In 2019, Trudeau announced that Canada would spend $14 billion to “support women and girls’ health around the world”, with half of the funds earmarked for sexual and reproductive health and rights. The funding envelope was to extend for 10 years. The $1.4 billion per year represents 9 percent of the approximately $16 billion Canada spent on foreign assistance in fiscal 2023 and 79 percent of the amount allocated to health. The Liberals’ most recent budget includes a further $4.2 billion over six years for the provision of contraception and abortion globally. This funding was included in the section of the budget document entitled “Upholding Canadian Values Around the World.”

It appears the ideological commitment to what is always termed “modern contraception” and abortion as the tickets to women’s freedom and economic independence precedes engagement with the countries in which Global Affairs is involved. David Mulroney, Canada’s former ambassador to China under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, has consistently hammered away at this point. “Far from deploying Canadian aid workers to African countries to listen, learn and craft policies that promote development in line with local goals and aspirations,” Mulroney said in an e-mail interview, “Canada simply transfers funds to its likeminded partners in multilateral organizations, progressive foundations, and the big abortion providers like Planned Parenthood.”

Billion-dollar business: A foreign aid effort that once focused on roads, bridges, immunization and schooling – and did not discriminate among favoured identity groups – now lavishes billions of dollars on sex-ed, contraception and abortion – couched euphemistically as support for “women and girls’ health around the world”. (*Sexual and reproductive health and rights.) (Source of graph: Global Affairs Canada)

Billion-dollar business: A foreign aid effort that once focused on roads, bridges, immunization and schooling – and did not discriminate among favoured identity groups – now lavishes billions of dollars on sex-ed, contraception and abortion – couched euphemistically as support for “women and girls’ health around the world”. (*Sexual and reproductive health and rights.) (Source of graph: Global Affairs Canada)

In many cases, Global Affairs is not doing the development work but outsources it to agenda-driven, left-leaning non-governmental organizations (NGO) whose missions align with that of the current government. A quick search of the government grant site gets 48 hits on the keywords “Planned Parenthood”. Many of these are smaller grants to local Planned Parenthood Canada offices through the government’s Summer Jobs program, but the search shows that close to $78 million has been provided to International Planned Parenthood or Action Canada through Global Affairs programming.

Given the level of funding that many of these organizations receive, and the close ideological affinity between the two parties, they cross the line from NGO to QUANGO, or quasi-non-governmental organization (better terms might be “pseudo-governmental organization” or “government proxy”). One example is Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights, also known as Planned Parenthood Canada. The organization disclosed in its 2022-2023 financial statements that close to 60 per cent of its annual funding is derived from government sources.

Global Affairs Canada delegates much of the program implementation to like-minded organizations such as Planned Parenthood, whose Canadian program funding is used to produce sex-ed (top) and school learning material with explicit (and wildly promotional) sexual content, and whose international branches distribute similar material in developing countries.

Global Affairs Canada delegates much of the program implementation to like-minded organizations such as Planned Parenthood, whose Canadian program funding is used to produce sex-ed (top) and school learning material with explicit (and wildly promotional) sexual content, and whose international branches distribute similar material in developing countries.

Much of the program funding is designated for sex-ed, which is couched in grant-writing language as a matter of access to reproductive rights. But the curriculum developed for these subsidized programs is not comprised of straightforward biology lessons with age-appropriate information about available forms of contraception. The keyword is “comprehensive” sexual education (CSE), which follows a “pleasure-based” methodology. The “right” to sexual pleasure – to “satisfy yourself”, as a Zambian government document aimed at children puts it – is now one of the reproductive rights children are being taught they are entitled to.

In 2020, Global Affairs funded a four-year, $11 million project with Action Canada and the International Planned Parenthood Federation entitled “Rights from the Start” that targeted four South American countries: Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana and Peru. To take a few selected development indicators, less than 20 percent of Ecuador’s road system is paved. The average life expectancy in Bolivia was 63.6 years in 2021 – and falling. Guyana’s was slightly higher – but also falling. Peru ranks 129th worldwide in the number of motor vehicles per capita.

Coercive diplomacy in action: Canada’s “Rights from the Start” project pushes unrestricted abortion access along with “gender equality outcomes” in Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana and Peru – countries where abortion is illegal or severely restricted and opposed by large proportions of the population. Shown, anti-abortion demonstrations in Quito, Ecuador (top) and La Paz, Bolivia (bottom). (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Dolores Ochoa; (bottom) AP Photo/Juan Karita)

Coercive diplomacy in action: Canada’s “Rights from the Start” project pushes unrestricted abortion access along with “gender equality outcomes” in Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana and Peru – countries where abortion is illegal or severely restricted and opposed by large proportions of the population. Shown, anti-abortion demonstrations in Quito, Ecuador (top) and La Paz, Bolivia (bottom). (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Dolores Ochoa; (bottom) AP Photo/Juan Karita)

But these nuts and bolts issues aren’t of any concern to the Action Canada project, which instead lists a number of expected “gender equality outcomes”, including the “strengthened capacity of partner organizations to develop and implement advocacy plans for the fulfilment of human rights comprehensive sexuality education.”

Abortion, interestingly, is illegal in Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, except for cases of rape, incest or endangerment to the mother’s life, and illegal after eight weeks’ gestation in Guyana. It is not a big leap to conclude that the choice of those four countries upon which to push unrestricted abortion is not accidental and that Global Affairs is essentially funding an activist group to lobby a foreign government to effect legal and political changes there. Whatever one thinks of abortion and how freely available it should be, such programs appear to cross the line from “development assistance” to ideologically driven political agitation.

The queer-nexus (aka LGBTQ2SI) funding also sees Global Affairs outsourcing program delivery to advocacy groups. In 2019 – the year Trudeau announced the $14 billion for women’s health – Bibeau announced $30 million over five years and $10 million in every subsequent year “to advance human rights and improve socio-economic outcomes for LGBTQ2 people in developing countries.” We are now a very long way from building the proverbial water well in the poor village – let alone one that’s available to every villager. Canada is instead targeting its expertise and its taxpayers’ funds at particular types of people deemed worthy of help – and they happen to be the very sorts of people the Trudeau Liberals also favour in their domestic policies.

One might think it would be hard to tie feminism, sexual liberation, queer- and transgenderism, foreign policy and climate policy all together but, according to the Government of Canada, ‘environment and climate action is a pillar of’ the Feminist International Assistance Policy.

Under an agreement entitled LGBTI Pathways, Global Affairs last year granted over $1 million to ILGA World (the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association) “to improve the lives of LGBTI persons across the world.” How was this goal to be achieved? Largely, it seems, by teaching global LGBTI organizations how to lobby for more funding. The project’s two expected outcomes were “enhanced awareness of donors on the priorities, strategies, and funding gaps of the international and regional LGBTI movements…and an increased capacity of LGBTI-led organizations…to advocate with donors to influence policy making and funding strategies.”

The same year, Global Affairs gave nearly $500,000 to Égides, a Francophone non-profit, to advance the “Rights and Well-being of LBTQI+ Women and Girls in West Africa and International Spaces.” Also in 2023, a Global Affairs-funded agreement with Rainbow Railroad, a U.S. and Canada based non-profit that “helps at-risk LGBTQI+ people get to safety worldwide,” provided $700,000 to conduct a meta-analysis, convene roundtables and hold a “3-day conference on policy issues related to forced displacements in a Global South transit country.”

One might think it would be hard to tie feminism, sexual liberation, queer- and transgenderism, foreign policy and climate policy all together but, according to the Government of Canada, “environment and climate action is a pillar of” the Feminist International Assistance Policy. Why would that be? “Research has shown,” the document continues, “that climate change and environmental degradation disproportionately affect women and girls, and that women and girls can be powerful agents of change if given access and control over environmental resources. Since the introduction of the [Feminist Policy], Canada has strengthened its work at the nexus of gender and climate action.” This has become a standard intersectional verbal slide of ministers and apparatchiks.

Improbable nexus: The Trudeau government’s foreign aid effort has somehow merged feminism, sexual liberation, transgenderism and climate-change policies – by, for example, claiming that “climate change and environmental degradation disproportionately affect women and girls.” (Sources of photos: (left) agroffman, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; (right) Julie Gorecki, retrieved from The Feminist Wire)

Improbable nexus: The Trudeau government’s foreign aid effort has somehow merged feminism, sexual liberation, transgenderism and climate-change policies – by, for example, claiming that “climate change and environmental degradation disproportionately affect women and girls.” (Sources of photos: (left) agroffman, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; (right) Julie Gorecki, retrieved from The Feminist Wire)

The Liberal policy also is being pushed by Canada’s left-wing opposition parties. In late May, NDP MP Laurel Collins addressed the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development, saying (at 16:00 in the linked video for May 23), “Climate emergencies are not gender neutral. The degradation of ecosystems disproportionately impacts women and girls, and I am wildly emotional. This is the existential crisis of our time.”

Whether it is actually occurring or not, this “existential crisis” is certainly costly, already resulting in the transfer of large amounts of money from taxpayers in the Frozen North. Canada is currently on the tail end of a five-year, $5.3 billion International Climate Finance Program that encourages recipient countries to adopt practices that may not even be to their benefit.

A portion of those billions was, for example, allotted to the Canadian Foodgrains Bank, which received $35 million to undertake a project entitled “Nature Positive Food Systems for Climate Change Adaptation.” The project “aims to improve low carbon, climate-resilient economies in rural areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique and Zimbabwe for enhanced well-being of communities, especially women, girls, and other vulnerable groups.”

Canada’s $35-million “Nature Positive Food Systems for Climate Change Adaptation” project seeks to enhance “well-being of communities, especially women, girls, and other vulnerable groups” in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique and Zimbabwe – countries where men live far shorter lives than women. Shown are rural areas of Ethiopia (top) and Kenya (bottom). (Sources of photos: (top) Rod Waddington, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; (bottom) ELIX, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Canada’s $35-million “Nature Positive Food Systems for Climate Change Adaptation” project seeks to enhance “well-being of communities, especially women, girls, and other vulnerable groups” in Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique and Zimbabwe – countries where men live far shorter lives than women. Shown are rural areas of Ethiopia (top) and Kenya (bottom). (Sources of photos: (top) Rod Waddington, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; (bottom) ELIX, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The average life expectancy at birth in these four countries is, incidentally, five-and-a-half to seven years longer for women than men, suggesting men might actually be the “vulnerable group”. Instead, men presumably will be left to fend for themselves in the allegedly hotter, drier, more hostile and unpredictable climate that is to come. Who knows, perhaps simply by stealing some of that delicious “nature-positive food” that will be grown by all those aid-receiving, longer-lived women and girls.

Even were we to stipulate that women and girls in certain developing countries are in greater need of Canadian largesse than their shorter-lived male compatriots, the evidence doesn’t appear to matter one way or the other, as the Liberals are immune to facts that undermine their woke agenda. Consider war-torn Ukraine, a country whose men are exposed to nearly all the risks of combat, do nearly all the fighting and dying – with 200,000 killed or wounded (many of them permanently crippled) since Russia’s invasion in February 2022 – and are subject to special laws preventing men aged 18-60 from leaving Ukraine, while over 6 million Ukrainian women and girls have sought safety abroad.

Among its aid programs, Canada in February announced it would contribute $4 million to help Ukraine remove some of the millions of dangerous mines sown during the war. But instead of focusing on the technical aspects of doing this difficult job safely and efficiently, i.e., getting the most mines removed for the effort expended, Canada has pressured Ukraine to ensure there are plenty of demining jobs for members of designated groups – namely women and transgenders. Along with this “gender-inclusive demining” aid, multiple other Canadian aid programs also explicitly tell the Ukrainian recipient agencies to focus “in particular [on] women and vulnerable groups” (other than men, of course).

“There is no Western nation that developed minus oil, minus [natural] gas,” says Jusper Machogu (top), a Kenyan engineer, farmer and advocate of modern agriculture and fossil fuel development in Africa, which he argues should be far higher priorities than worrying about the threat of future climate change. At bottom, Kenyan farm workers process maize in Uasin Gishu County. (Source of bottom photo: Jen Watson/Shutterstock)

“There is no Western nation that developed minus oil, minus [natural] gas,” says Jusper Machogu (top), a Kenyan engineer, farmer and advocate of modern agriculture and fossil fuel development in Africa, which he argues should be far higher priorities than worrying about the threat of future climate change. At bottom, Kenyan farm workers process maize in Uasin Gishu County. (Source of bottom photo: Jen Watson/Shutterstock)

Returning to the issue of climate, there are plenty of Africans who believe their continent is facing bigger and more immediate problems than the threat of future climate change. Jusper Machogu, for example, is a young Kenyan man who uses social media to advocate “fossil fuels for Africa” because he believes Africans above all need access to reliable, affordable energy. “Most people over here don’t really know what [the UN’s] Sustainable Development Goals are about or what the UN is truly doing in Africa,” Machogu says in a lengthy interview. “They say that there are these 17 big problems that Africans, or developing countries are facing. I’m surprised to see climate change as one of those problems.”

Machogu bristles at the hypocrisy of prosperous aid-giving countries now expecting Africa to develop in an ideologically prescribed – and, he argues, ineffective – manner. “There is no western nation that developed minus oil, minus [natural] gas,” he notes. “The four pillars of modern civilization are cement, fertilizer, plastics and steel.” This is the core argument made in How the World Really Works, the 2022 book by Vaclav Smil, Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Manitoba (Smil specifically cited ammonia, a key constituent of fertilizer). Machogu says Africa requires much more of each pillar – and all four in turn depend on large amounts of plentiful, affordable and reliable energy to produce (with fertilizer and steel also containing a fossil fuel as an ingredient).

Machogu remains unconvinced that solar and wind power – which are expensive, intermittent and unreliable – are the solution for Africa. ‘What’s going to make an average African rich?’ he asks rhetorically. ‘Solving agriculture.’

In addition, natural gas and propane are much cleaner-burning fuels than the wood and dung still used by millions for cooking and heating. There’s even a gender-equity dimension, notes journalist Anthony Furey in a recent column: millions of African women and girls spend hours each day walking in search of wood fuel and carrying it back home. Making fossil fuels widely available at reasonable cost could begin to liberate them from this drudgery while improving air quality in homes and villages.

But instead of helping Africa develop more of its significant oil and natural gas potential, Western nations and multilateral institutions are relentlessly pushing wind and solar power. “They say we’re going to get you loans, but if we’re going to give you a loan, you must invest in renewable energy,” says Machogu. “When they say renewable energy, they don’t mean hydro or geothermal. Power usually means solar and wind.”

“If we’re going to give you a loan, you must invest in renewable energy”: Global Affairs Canada and other globalist institutions seek to control Africa’s development by agreeing to sponsor only solar and wind energy. Shown at left, solar panels outside shacks in a remote village with no electricity in rural Woqooyi Galbeed region, Somalia; at right, a wind and solar power installation on a farm in Upington, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. (Sources of photos: (left) Voyage View Media/Shutterstock; (right) Grobler du Preez/Shutterstock)

“If we’re going to give you a loan, you must invest in renewable energy”: Global Affairs Canada and other globalist institutions seek to control Africa’s development by agreeing to sponsor only solar and wind energy. Shown at left, solar panels outside shacks in a remote village with no electricity in rural Woqooyi Galbeed region, Somalia; at right, a wind and solar power installation on a farm in Upington, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. (Sources of photos: (left) Voyage View Media/Shutterstock; (right) Grobler du Preez/Shutterstock)

He is certainly right about Global Affairs Canada. A recent analysis by the Epoch Times shows that aid for renewable energy was the fastest-rising category of foreign assistance, reaching $555 million in fiscal 2023, and expected to rise further in the coming years. Virtually zero was allocated to natural gas or even nuclear energy, which emits no carbon dioxide while generating electricity. Meanwhile, spending on traditional bread-and-butter areas like transportation, storage and disaster risk reduction has been cut sharply in recent years.

Machogu remains unconvinced that solar and wind power – which are expensive, intermittent and unreliable – are the solution for Africa. “What’s going to make an average African rich?” he asks rhetorically. “Solving agriculture. Today about six to seven out of 10 Africans rely on agriculture for their livelihood. How do we solve agriculture? Of course, we need fossil fuels. We need farm machinery. We need irrigation. We need nitrogenous fertilizers. That’s what the crop needs to grow or to do better.”

The West’s climate fixation means that oil and natural gas development in Africa remains woefully underfunded, and hydroelectric facilities receive much of their capital from Communist China. Shown at top, liquefied natural gas project at Cabo Delgado, Mozambique; middle, the Mukuyu-1 exploration well in Zimbabwe’s Cabora Bassa Basin; bottom, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which will generate 5,100 megawatts of electricity on the Blue Nile. (Sources of photos: (top) Sigrid Ekman, retrieved from African Arguments; (middle) The Africa Report; (bottom) Daily News Egypt)

The West’s climate fixation means that oil and natural gas development in Africa remains woefully underfunded, and hydroelectric facilities receive much of their capital from Communist China. Shown at top, liquefied natural gas project at Cabo Delgado, Mozambique; middle, the Mukuyu-1 exploration well in Zimbabwe’s Cabora Bassa Basin; bottom, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which will generate 5,100 megawatts of electricity on the Blue Nile. (Sources of photos: (top) Sigrid Ekman, retrieved from African Arguments; (middle) The Africa Report; (bottom) Daily News Egypt)

But on this issue, Canada is as stubborn as the EU, the World Bank and other international organizations with which its policies are aligned, refusing to provide any loans or other financial assistance for oil and natural gas development in Africa. As Machogu notes, even hydroelectric dams – a foundation of the electricity networks in numerous Western countries, especially Canada – are now virtually anathema. Ethiopia, for example, recently began producing power from the enormous Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the fabled Blue Nile, and wishes to build several more dams on other rivers. It seems a reasonable goal, as barely half of its population has access to electricity.

And yet while this dam site was originally surveyed using U.S. aid money in the 1960s, Western nations bowed out of the project one by one, while environmental groups as well as neighbouring Egypt fought vehemently against it, and the World Bank now stubbornly pushes only wind, solar and geothermal power. So Ethiopia had to scratch together funding from its own meagre public finances, from crowd-funding, investment by dam employees and, finally, a $1 billion loan from China. China unapologetically uses aid to advance its geopolitical agenda while enriching Chinese construction companies and equipment manufacturers to which some of the loan funds are tied. The story has been similar on several other recent Ethiopian dam projects. These are foreign policy win-wins for China, Ethiopia gets its dams – and Western nations look arrogant and inept.

Canada’s Liberal Party prides itself on its woke bona fides. From the early days of Trudeau’s appointment of a gender-equitable Cabinet “because it’s 2015” to its intimate ties with Canada 2020, the self-described “upstart think-tank for Canada’s progressive community”, the current government understands itself as a standard-bearer of progressivism. Most Canadians know that by now; but most perhaps don’t know that this agenda extends to pretty much every South American or African village where Canadian aid money finds its way.

To Ekeocha, the 21st century coercive diplomacy and haughty ideological conditions evoke sinister overtones of relations in past centuries. ‘Many Western leaders have revealed themselves to be modern colonial masters, threatening to withdraw aid from countries such as Nigeria and Uganda unless they accept their global sexual agenda,’ she writes.

After one recovers from the eye-watering – and rising – amounts of money that the federal government is spending on climate, contraception and the queer-nexus triad, the next question is, is it money well-spent? Even if you are ideologically aligned with the goals, are the people Canada’s government favours in developing countries – women, girls and LGBTQI+ – less poor than they were before? More climate-resilient? Eating nature-positive foods? Where is any bang for the billions of Canadian bucks? In what world could this magic be brought into effect, one where reducing the carbon footprint, providing contraception and changing the mores in developing countries increases the safety and wealth not only of the (sometimes unwilling) recipients, but of Canadians (as Freeland claimed her policy aims to do)?

The experience of other aid-giving countries suggests such an approach does not work and eventually may even backfire in the donor country. Freeland and Bibeau may have taken their lead in crafting the 2017 Feminist International Assistance Program from Sweden, which in 2014 had adopted a similar policy directive. Perhaps Global Affairs Canada should look once more to the Nordic country, because in 2022 Sweden announced it was abandoning its feminist foreign policy. Tobias Billström, Sweden’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, that year told the newspaper Aftonbladet that, “Gender equality is a fundamental value in Sweden and also for this government, but we’re not going to continue with a feminist foreign policy because the label obscures the fact the Swedish foreign policy must be based on Swedish values and Swedish interests.”

Pushback from aid-receiving countries: “Many Western leaders have revealed themselves to be modern colonial masters,” asserts Nigerian scientist Obianuju Ekeocha, who warns of the West’s manipulative tactics to impose the globalist agenda on Africa. (Source of photo: Catholic Digest)

Pushback from aid-receiving countries: “Many Western leaders have revealed themselves to be modern colonial masters,” asserts Nigerian scientist Obianuju Ekeocha, who warns of the West’s manipulative tactics to impose the globalist agenda on Africa. (Source of photo: Catholic Digest)

Something needs to give in Canada as well, because not only is the current approach not working, there’s at least some evidence it’s angering more and more people in aid-receiving countries. Groups have been founded, in fact, specifically to oppose Western aid if it comes with too high an ideological price.

Obianuju Ekeocha is a Nigerian scientist and founder of Culture of Life Africa, an organization that seeks to push back against what it terms “unbelievable cultural pressure that is beginning to erode and alter the trajectory of the African cultural values of life, marriage, motherhood, family and faith.” She has written and spoken extensively on the misalignment between the actual needs and desires of African women and the funding priorities of Western nations. To her, the 21st century coercive diplomacy and haughty ideological conditions evoke sinister overtones of relations in past centuries. “Many Western leaders have revealed themselves to be modern colonial masters, threatening to withdraw aid from countries such as Nigeria and Uganda unless they accept their global sexual agenda,” Ekeocha writes in her 2018 book Target Africa: Ideological Neo-Colonialism Of The Twenty-First Century.

Machogu, for his part, goes even further. “I think it boils down to [a goal of] depopulation,” is his stark assessment. “They’re trying to keep Africa poor.”

Anna Farrow is a Montreal-based journalist for The Catholic Register.

Source of main image: Shutterstock.