Fraser Institute

Yes, B.C.’s Land Act changes give First Nations veto over use of Crown Land

From the Fraser Institute

By Bruce Pardy

Nathan Cullen says there’s no veto. Cullen, British Columbia’s Minister of Water, Land, and Resource Stewardship, plans to give First Nations joint decision-making authority over Crown land. His NDP government recently opened consultations on its proposal to amend the B.C. Land Act, under which the minister grants leases, licences, permits, rights-of-way and land sales. The amendments will give legal effect to agreements with Indigenous governing bodies. Those agreements will share decision-making power “through joint or consent models” with some or all of B.C.’s more than 200 First Nations.

Yes, First Nations will have a veto.

Cullen denies it. “There is no veto in these amendments,” he told the Nanaimo News Bulletin last week. He accused critics of fearmongering and misinformation. “My worry is that for some of the political actors here on the right, this is an element of dog-whistle politics.”

But Cullen has a problem. Any activity that requires your consent is an activity over which you have a veto. If a contract requires approval of both parties before something can happen, “no” by one means “no” for both. The same is true in other areas of law such as sexual conduct, which requires consent. If you withhold your consent, you have vetoed the activity. “Joint decision-making,” “consent,” and “veto” come out to the same thing.

Land use decisions are subject to the same logic. The B.C. government will give First Nations joint decision-making power, when and where agreements are entered into. Its own consultation materials say so. This issue has blown up in the media, and the government has hastily amended its consultation webpage to soothe discontent (“The proposed amendments to the Land Act will not lead to broad, sweeping, or automatic changes (or) provide a ‘veto.’”) Nothing to see here folks. But its documentation continues to describe “shared decision-making through joint or consent models.”

These proposals should not surprise anyone. In 2019, the B.C. legislature passed Bill 41, the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA). It requires the government to take “all measures necessary” to make the laws of British Columbia consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP).

UNDRIP is a declaration of the U.N. General Assembly passed in 2007. It says that Indigenous people have “the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired… to own, use, develop and control.”

On its own, UNDRIP is non-binding and unenforceable. But DRIPA seeks to incorporate UNDRIP into B.C. law, obligating the government to achieve its aspirations. Mere consultation with First Nations, which Section 35 of the Constitution requires, won’t cut it under UNDRIP. Under Section 7 of DRIPA, agreements to be made with indigenous groups are to establish joint decision-making or to require consent of the Indigenous group. Either Cullen creates a First Nations veto or falls short of the goalposts in DRIPA. He is talking out of both sides of his mouth.

Some commentators warned against these dangers long ago. For example, shortly after DRIPA was passed in 2019, Vancouver lawyer Robin Junger wrote in the Vancouver Sun, “It will likely be impossible for government to live up to the expectations that Indigenous groups will now reasonably hold, without fundamentally affecting the rights and interests of third parties.” Unfortunately, few wanted to tackle that thorny question head on at the time. All three political parties in B.C. voted in favour of DRIPA, which passed unanimously.

For a taste of how Land Act changes could work, ask some B.C. residents who have private docks. In Pender Harbour, for instance, the shishalh Nation and the province have jointly developed a “Dock Management Plan” to try and impose various new and onerous rules on private property owners (including red “no go” zones and rules that will make many existing docks and boat houses non-compliant). Property owners with long-standing docks in full legal compliance will have no right to negotiate, to be consulted, or to be grandfathered. Land Act amendments may hardwire this plan into B.C. law.

Yet Cullen insists that no veto will exist since aggrieved parties can apply to a court for judicial review. “[An agreement] holds both parties—B.C. and whichever nation we enter into an agreement (with)—to the same standard of judicial review, administrative fairness, all the things that courts protect when someone is going through an application or a tendering process,” he told Business in Vancouver.

This is nonsense on stilts. By that standard, no government official has final authority under any statute. All statutory decisions are potentially subject to judicial review, including decisions of Cullen himself as the minister responsible for the Land Act. He doesn’t have a veto? Of course he does. Moreover, courts on judicial review generally defer to statutory decision-makers. And they don’t change decisions but merely send them back to be made again. The argument that First Nations won’t have a veto because their decisions can be challenged on judicial review is legal jibber jabber.

When the U.N. passed UNDRIP in 2007, people said they can’t be serious. When the B.C. legislature passed DRIPA in 2019, people said they can’t be serious. The B.C. government now proposes to give First Nations a veto over the use of Crown land. Don’t worry, they can’t be serious.

Author:

Alberta

New pipeline from Alberta would benefit all Canadians—despite claims from B.C. premier

From the Fraser Institute

The pending Memorandum of Understanding between the Carney government and the Alberta governments will reportedly support a new oil pipeline from Alberta’s oilsands to British Columbia’s tidewater. But B.C. Premier David Eby continues his increasingly strident—and factually challenged—opposition to the whole idea.

Eby’s arguments against a new pipeline are simply illogical and technically incorrect.

First, he argues that any pipeline would pose unmitigated risks to B.C.’s coastal environment, but this is wrong for several reasons. The history of oil transport off of Canada’s coasts is one of incredible safety, whether of Canadian or foreign origin, long predating federal Bill C-48’s tanker ban. New pipelines and additional transport of oil from (and along) B.C. coastal waters is likely very low environmental risk. In the meantime, a regular stream of oil tankers and large fuel-capacity ships have been cruising up and down the B.C. coast between Alaska and U.S. west coast ports for decades with great safety records.

Next, Eby argues that B.C.’s First Nations people oppose any such pipeline and will torpedo energy projects in B.C. But in reality, based on the history of the recently completed Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) pipeline, First Nations opposition is quite contingent. The TMX project had signed 43 mutual benefit/participation agreements with Indigenous groups along its route by 2018, 33 of which were in B.C. As of March 2023, the project had signed agreements with 81 out of 129 Indigenous community groups along the route worth $657 million, and the project had resulted in more than $4.8 billion in contracts with Indigenous businesses.

Back in 2019, another proposed energy project garnered serious interest among First Nations groups. The First Nations-proposed Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor, aimed to connect Alberta’s oilpatch to a port in Kitimat, B.C. (and ultimately overseas markets) had the buy-in of 35 First Nations groups along the proposed corridor, with equity-sharing agreements floated with 400 others. Energy Spirit, unfortunately, died in regulatory strangulation in the Trudeau government’s revised environmental assessment process, and with the passage of the B.C. tanker ban.

Premier Eby is perfectly free to opine and oppose the very thought of oil pipelines crossing B.C. But the Supreme Court of Canada has already ruled in a case about the TMX pipeline that B.C. does not have the authority to block infrastructure of national importance such as pipelines.

And it’s unreasonable and corrosive to public policy in Canada for leading government figures to adopt positions on important elements of public policy that are simply false, in blatant contradiction to recorded history and fact. Fact—if the energy industry is allowed to move oil reserves to markets other than the United States, this would be in the economic interest of all Canadians including those in B.C.

It must be repeated. Premier Eby’s objections to another Alberta pipeline are rooted in fallacy, not fact, and should be discounted by the federal government as it plans an agreement that would enable a project of national importance.

Business

Taxpayers paying wages and benefits for 30% of all jobs created over the last 10 years

From the Fraser Institute

By Jason Childs

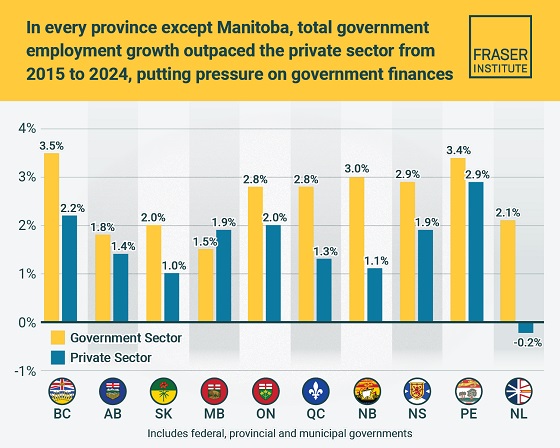

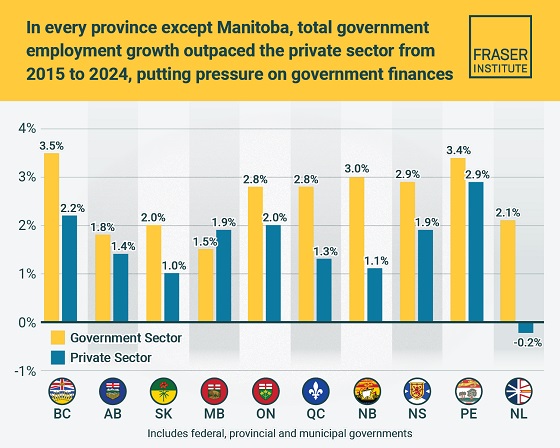

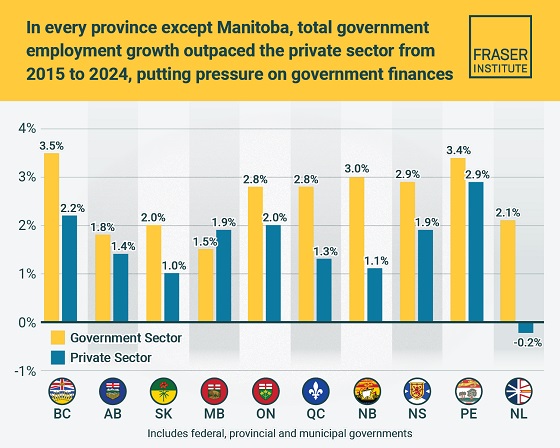

From 2015 to 2024, the government sector in Canada—including federal, provincial and municipal—added 950,000 jobs, which accounted for roughly 30 per cent of total employment growth in the country, finds a new study published today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“In Canada, employment in the government sector has skyrocketed over the last 10 years,” said Jason Childs, a professor of economics at the University of Regina, senior fellow at the Fraser Institute and author of Examining the Growth of Public-Sector Employment Since 2015.

Over the same 10-year period (2015-2024), government-sector employment grew at an annual average rate of 2.7 per cent compared to only 1.7 per cent for the private sector. The study also examines employment growth by province. Government employment (federal, provincial, municipal) grew at a higher annual rate than the private sector in every province except Manitoba over the 10-year period.

The largest gaps between government-sector employment growth compared to the private sector were in Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Quebec and British Columbia. The smallest gaps were in Alberta and Prince Edward Island.

“The larger government’s share of employment, the greater the ultimate burden on taxpayers to support government workers—government does not pay for itself,” Childs said.

A related study (Measuring the Cost to Canadians from the Growth in Public Administration, also authored by Childs) finds that, from 2015 to 2024, across all levels of government in Canada, the number of public administrators (many of who

work in government ministries, agencies and other offices that do not directly provide services to the public) grew by more than 328,000—or 3.5 per cent annually (on average).

“If governments want to reduce costs, they should look closely at the size of their public administration,” Childs said.

Examining the Growth of Public Sector Employment Since 2015

-

COVID-1923 hours ago

COVID-1923 hours agoCrown seeks to punish peaceful protestor Chris Barber by confiscating his family work truck “Big Red”

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoHealth Canada suggests MAiD expansion by pre-approving ‘advance requests’

-

Agriculture11 hours ago

Agriculture11 hours agoHealth Canada indefinitely pauses plan to sell unlabeled cloned meat after massive public backlash

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoPremier Danielle Smith says attacks on Alberta’s pro-family laws ‘show we’ve succeeded in a lot of ways’

-

Indigenous1 day ago

Indigenous1 day agoCanadian mayor promises to ‘vigorously defend’ property owners against aboriginal land grab

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTaxpayers paying wages and benefits for 30% of all jobs created over the last 10 years

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoOrgan donation industry’s redefinitions of death threaten living people

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoEXCLUSIVE: Here’s An Inside Look At The UN’s Disastrous Climate Conference