Health

Was football player Terrance Howard really dead? His parents didn’t think so.

From LifeSiteNews

The Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) states that there must be an irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain for a declaration of brain death. The way doctors currently diagnose brain death does not comply with the law under the UDDA.

North Carolina Central University football player Terrance Howard died recently after a car accident reportedly left him “brain dead.” But his family disputed this diagnosis and requested that their son be transferred to another facility for treatment of his brain injury, leading to conflict with Terrance’s doctors and hospital. According to News One, his parents claimed that Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center wanted to kill their son for his organs, and accused doctors of snickering and laughing while refusing to help him. His father, Anthony Allen, told News One that the hospital removed Terrance from life support against his family’s wishes and forcibly ejected his family from his room. The family posted videos on social media of apparent police officers entering Terrance’s hospital room, and said that the hospital threatened them with criminal action for trespassing.

If these allegations are true, the Howard family has every right to be outraged at the disrespectful treatment they received at Atrium Health. Especially now, as the legitimacy of brain death is coming under increasing scrutiny, it is outrageous that hospitals and doctors continue being so heavy-handed. The National Catholic Bioethics Center (NCBC), formerly a staunch supporter of “brain death,” released a statement in April 2024, saying:

Events in the last several months have revealed a decisive breakdown in a shared understanding of brain death (death by neurological criteria) which has been critical in shaping the ethical practice of organ transplantation. At stake now is whether clinicians, potential organ donors, and society can agree on what it means to be dead before vital organs are procured.

The NCBC statement was prompted by the newest brain death guideline which explicitly allows people with partial brain function to be declared brain dead. But the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) states that there must be an irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain for a declaration of brain death. The way doctors currently diagnose brain death does not comply with the law under the UDDA.

Terrance Howard’s story is reminiscent of the mistreatment of another Black teenager, Jahi McMath. In 2013, Jahi was a quiet, cautious teenager with sleep apnea who underwent a tonsillectomy and palate reconstruction to improve her airflow while sleeping. An hour after the surgery, she started spitting up blood. Her parents requested repeatedly to see a doctor without success. Her mother, Nailah Winkfield, said, “No one was listening to us, and I can’t prove it, but I really feel in my heart: if Jahi was a little white girl, I feel we would have gotten a little more help and attention.”

Jahi continued to bleed until she had a cardiac arrest just after midnight. She was pulseless for ten minutes during her “code blue” resuscitation. Two days later, her electroencephalogram (EEG) was flatline, and it was clear that Jahi had suffered a severe brain injury which was worsening. But rather than treating these findings aggressively, her doctors proceeded toward a diagnosis of brain death. Three days after her surgery, her parents were informed that their daughter was “dead” and that Jahi could now become an organ donor. The family was stunned. How could Jahi be dead? She was warm, she was moving occasionally, and her heart was still beating. As a Christian, Nailah believed her daughter’s spirit remained in her body as long as her heart continued to beat. While the family sought medical and legal assistance, Children’s Hospital Oakland doubled down, refusing to feed Jahi for three weeks. The hospital finally agreed to release Jahi to the county coroner for a death certificate, following which her family would be responsible for her.

On January 3, 2014, Jahi received a death certificate from California, listing her cause of death as “Pending Investigation.” Why was the hospital so adamant about insisting Jahi was dead, even to the point of issuing a death certificate? Possibly because California’s Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act limits noneconomic damages to $250,000. If Jahi was “dead,” the hospital and its malpractice insurer would only be liable for $250,000. But if Jahi was alive, there would be no limit to the amount her family could claim for her ongoing care.

After Jahi was transferred to New Jersey, the only US state with a religious exemption to a diagnosis of brain death, she began to improve. After noticing that Jahi’s heart rate would decrease at the sound of her mother’s voice, the family began asking her to respond to commands, and videoed her correct responses. Jahi went through puberty and began to menstruate — something not seen in corpses! By August 2014 she was stable enough to move into her mother’s apartment for continuing care. Subsequently Jahi was examined by two neurologists (Dr. Calixto Machado and Dr. D. Alan Shewmon) who found that she had definitely improved: she no longer met the criteria for brain death and was in a minimally conscious state. Jahi continued responding to her family in a meaningful way until her death in June 2018 from complications of liver failure.

How could Jahi McMath, who was declared brain dead by three doctors, who failed three apnea tests, and who had four flatline EEGs and a radioisotope scan showing no intracranial blood flow, go on to recover neurologic function? Very likely, due to a condition called Global Ischemic Penumbra, or GIP. Like every other organ, the brain shuts down its function when its blood flow is reduced in order to conserve energy. At 70 percent of normal blood flow, the brain’s neurological functioning is reduced, and at a 50 percent reduction the EEG becomes flatline. But tissue damage doesn’t begin until blood flow to the brain drops below 20 percent of normal for several hours. GIP is a term doctors use to refer to that interval when the brain’s blood flow is between 20 and 50 percent of normal. During GIP the brain will not respond to neurological testing and has no electrical activity on EEG, but still has enough blood flow to maintain tissue viability — meaning that recovery is still possible. During GIP, a person will appear “brain dead” using the current medical guidelines and testing, but with continuing care they could potentially improve.

Dr. D. Alan Shewmon, one of the world’s leading authorities on brain death, describes GIP this way:

This [GIP] is not a hypothesis but a mathematical necessity. The clinically relevant question is therefore not whether GIP occurs but how long it might last. If, in some patients, it could last more than a few hours, then it would be a supreme mimicker of brain death by bedside clinical examination, yet the non-function (or at least some of it) would be in principle reversible.

Dr. Cicero Coimbra first described GIP in 1999, but in the never-ending quest for transplantable organs, his work has been largely ignored. There is absolutely no medical or moral certainty in a brain death diagnosis, and people need to be made aware of this. “Brain dead” people are very ill, and their prognosis may be death, but they deserve to be treated aggressively until they either recover or succumb to natural death. Unfortunately, as the family of Terrance Howard seems to have experienced, doctors are continuing to use a brain death guideline that ignores the reality of GIP and does not comply with brain death law under the UDDA.

Heidi Klessig MD is a retired anesthesiologist and pain management specialist who writes and speaks on the ethics of organ harvesting and transplantation. She is the author of “The Brain Death Fallacy” and her work may be found at respectforhumanlife.com.

Business

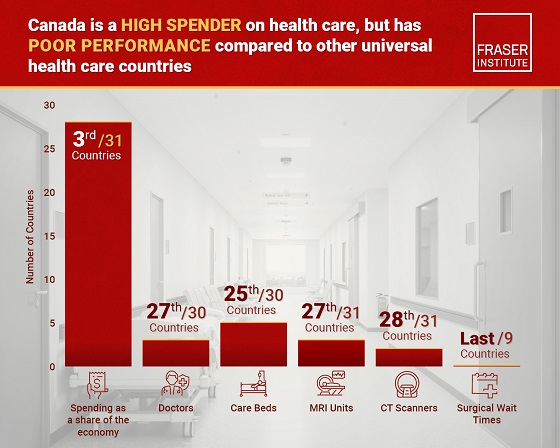

Canada has fewer doctors, hospital beds, MRI machines—and longer wait times—than most other countries with universal health care

From the Fraser Institute

Despite a relatively high level of spending, Canada has significantly fewer doctors, hospital beds, MRI machines and CT scanners compared to other countries with universal health care, finds a new study released today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“There’s a clear imbalance between the high cost of Canada’s health-care system and the actual care Canadians receive in return,” said Mackenzie Moir, senior policy

analyst at the Fraser Institute and author of Comparing Performance of Universal Health-Care Countries, 2025.

In 2023, the latest year of available comparable data, Canada spent more on health care (as a percentage of the economy/GDP, after adjusting for population age) than

most other high-income countries with universal health care (ranking 3rd out of 31 countries, which include the United Kingdom, Australia and the Netherlands).

And yet, Canada ranked 27th (of 30 countries) for the availability of doctors and 25th (of 30) for the availability of hospital beds.

In 2022, the latest year of diagnostic technology data, Canada ranked 27th (of 31 countries) for the availability of MRI machines and 28th (of 31) for CT scanners.

And in 2023, among the nine countries with universal health-care systems included in the Commonwealth Fund’s International Health Policy Survey, Canada ranked last for the percentage of patients able to make same- or next-day appointments when sick (22 per cent) and had the highest percentage of patients (58 per cent) who waited two months or more for non-emergency surgery. For comparison, the Netherlands had much higher rates of same- or next-day appointments (47 per cent) and much lower waits of two months or more for non-emergency surgery (20 per cent).

“To improve health care for Canadians, our policymakers should learn from other countries around the world with higher-performing universal health-care systems,”

said Nadeem Esmail, director of health policy at the Fraser Institute.

Comparing Performance of Universal Health Care Countries, 2025

- Of the 31 high-income universal health-care countries, Canada ranks among the highest spenders, but ranks poorly on both the availability of most resources and access to services.

- After adjustments for differences in the age of the population of these 31 countries, Canada ranked third highest for spending as a percentage of GDP in 2023 (the most recent year of comparable data).

- Across 13 indictors measured, the availability of medical resources and timely access to medical services in Canada was generally below that of the average OECD country.

- In 2023, Canada ranked 27th (of 30) for the relative availability of doctors and 25th (of 30) for hospital beds dedicated to physical care. In 2022, Canada ranked 27th (of 31) for the relative availability of Magnetic Resonance Im-aging (MRI) machines, and 28th (of 31) for CT scanners.

- Canada ranked last (or close to last) on three of four indicators of timeliness of care.

- Notably, among the nine countries for which comparable wait times measures are available, Canada ranked last for the percentage of patients reporting they were able to make a same- or next-day appointment when sick (22%).

- Canada also ranked eighth worst for the percentage of patients who waited more than one month to see a specialist (65%), and reported the highest percentage of patients (58%) who waited two months or more for non-emergency surgery.

- Clearly, there is an imbalance between what Canadians get in exchange for the money they spend on their health-care system.

Mackenzie Moir

Senior Policy Analyst, Fraser Institute

Business

Cutting Red Tape Could Help Solve Canada’s Doctor Crisis

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

Doctors waste millions of hours on useless admin. It’s enough to end Canada’s doctor shortage. Ian Madsen says slashing red tape, not just recruiting, is the fastest fix for the clogged system.

Doctors spend more time on paperwork than on patients and that’s fueling Canada’s health care wait lists

Canada doesn’t just lack doctors—it squanders the ones it has. Mountains of paperwork and pointless admin chew up tens of millions of physician hours every year, time that could erase the so-called shortage and slash wait lists if freed for patient care.

Recruiting more doctors helps, but the fastest cure for our sick system is cutting the bureaucracy that strangles the ones already here.

The Canadian Medical Association found that unnecessary non-patient work consumes millions of hours annually. That’s the equivalent of 50.5 million patient visits, enough to give every Canadian at least one appointment and likely erase the physician shortage. Meanwhile, the Canadian Institute for Health Information estimates more than six million Canadians don’t even have a family doctor. That’s roughly one in six of us.

And it’s not just patients who feel the shortage—doctors themselves are paying the price. Endless forms don’t just waste time; they drive doctors out of the profession. Burned out and frustrated, many cut their hours or leave entirely. And the foreign doctors that health authorities are trying to recruit? They might think twice once they discover how much time Canadian physicians spend on paperwork that adds nothing to patient care.

But freeing doctors from forms isn’t as simple as shredding them. Someone has to build systems that reduce, rather than add to, the workload. And that’s where things get tricky. Trimming red tape usually means more Information Technology (IT), and big software projects have a well-earned reputation for spiralling in cost.

Bent Flyvbjerg, the global guru of project disasters, and his colleagues examined more than 5,000 IT projects in a 2022 study. They found outcomes didn’t follow a neat bell curve but a “power-law” distribution, meaning costs don’t just rise steadily, they explode in a fat tail of nasty surprises as variables multiply.

Oxford University and McKinsey offered equally bleak news. Their joint study concluded: “On average, large IT projects run 45 per cent over budget and seven per cent over time while delivering 56 per cent less value than predicted.” If that sounds familiar, it should. Canada’s Phoenix federal payroll fiasco—the payroll software introduced by Ottawa that left tens of thousands of federal workers underpaid or unpaid—is a cautionary tale etched into the national memory.

The lesson isn’t to avoid technology, but to get it right. Canada can’t sidestep the digital route. The question is whether we adapt what others have built or design our own. One option is borrowing from the U.S. or U.K., where electronic health record (EHR) systems (the digital patient files used by doctors and hospitals) are already in place. Both countries have had headaches with their systems, thanks to legal and regulatory differences. But there are signs of progress.

The U.K. is experimenting with artificial intelligence to lighten the administrative load, and a joint U.K.-U.S. study gives a glimpse of what’s possible:

“… AI technologies such as Robotic Process Automation (RPA), predictive analytics, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) are transforming health care administration. RPA and AI-driven software applications are revolutionizing health care administration by automating routine tasks such as appointment scheduling, billing, and documentation. By handling repetitive, rule-based tasks with speed and accuracy, these technologies minimize errors, reduce administrative burden, and enhance overall operational efficiency.”

For patients, that could mean fewer missed referrals, faster follow-up calls and less time waiting for paperwork to clear before treatment. Still, even the best tools come with limits. Systems differ, and customization will drive up costs. But medicine is medicine, and AI tools can bridge more gaps than you might think.

Run the math. If each “freed” patient visit is worth just $20—a conservative figure for the value of a basic appointment—the payoff could hit $1 billion in a single year.

Updating costs would continue, but that’s still cheap compared to the human and financial toll of endless wait lists. Cost-sharing between provinces, Ottawa, municipalities and even doctors themselves could spread the risk. Competitive bidding, with honest budgets and realistic timelines, is non-negotiable if we want to dodge another Phoenix-sized fiasco.

The alternative—clinging to our current dysfunctional patchwork of physician information systems—isn’t really an option. It means more frustrated doctors walking away, fewer new ones coming in, and Canadians left to languish on wait lists that grow ever longer.

And that’s not health care—it’s managed decline.

Ian Madsen is a senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

City of Red Deer1 day ago

City of Red Deer1 day agoPlan Ahead: Voting May Take a Little Longer This Election Day

-

Crime22 hours ago

Crime22 hours agoFrance stunned after thieves loot Louvre of Napoleon’s crown jewels

-

Uncategorized1 day ago

Uncategorized1 day agoNew report warns WHO health rules erode Canada’s democracy and Charter rights

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoUS government buys stakes in two Canadian mining companies

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoMinus Forty and the Myth of Easy Energy

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoOttawa Should Think Twice Before Taxing Churches

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoMétis will now get piece of ever-expanding payout pie

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoBusting five myths about the Alberta oil sands