Business

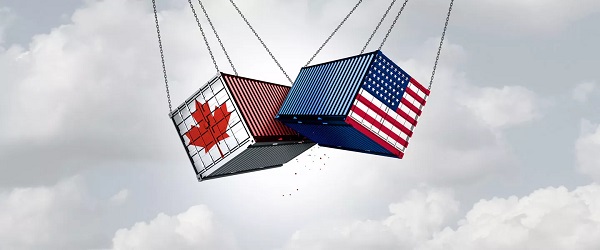

Trade retaliation might feel good—but it will hurt Canada’s economy

From the Fraser Institute

To state the obvious, president-elect Donald Trump’s threat to impose an across-the-board 25 per cent tariff on Canadian exports to the United States has gotten the attention of Canadian policymakers who are considering ways to retaliate.

Reportedly, if Trump makes good on his tariff threat, the federal government may levy retaliatory tariffs on a wide range of American-made goods including orange juice, ceramic products such as sinks and toilets, and some steel products. And NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh said he wants Canada to block exports of critical minerals such as aluminum, lithium and potash to the United States, saying that if Trump “wants to pick a fight with Canada, we have to make sure it’s clear that it’s going to hurt Americans as well.”

Indeed, the ostensible goal of tariff retaliation is to inflict economic damage on producers and workers in key U.S. jurisdictions while minimizing harm to Canadian consumers of products imported from the U.S. The hope is that there will be sufficient political blowback from Canada’s retaliation that Republican members of Congress will eventually view Trump’s tariffs as an unacceptable risk to their re-election and pressure him to roll them back.

But while Canadians might feel good about tit-for-tat retaliation against Trump’s trade bullying and taunting, it might well make things worse for the Canadian economy. For example, even selective tariffs will increase the cost of living for Canadians as importers of tariffed U.S. goods pass the tax along to domestic consumers. Retaliatory tariffs might also harm productivity growth in Canada by encouraging increased domestic production of goods that are produced relatively inefficiently here at home compared to in the U.S. Make no mistake—once trade protections are put in place, the beneficiaries have a strong vested interest in having the protections maintained indefinitely. While Trump will be gone in four years, tariffs imposed by Ottawa to retaliate against his actions will likely remain in place for longer.

The U.S. president has substantial leeway under existing legislation to implement trade measures such as tariffs. While Trump has several legislative options to impose new tariffs against Canada and Mexico, he’ll likely use the International Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA), which grants the president power to regulate imports and impose duties in response to an emergency involving any unusual and extraordinary threat to national security, foreign policy or the economy. According to Trump’s rhetoric, the emergency is illegal immigration and drug traffic originating in Canada and Mexico.

However risible Trump’s emergency claim might be when applied to Canada, overturning any action under the IEEPA, or some other enabling legislation, would require a legal challenge. And in fact, because no president has yet used the IEEPA to impose tariffs, the legality of Trump’s actions remains in doubt. In this context, a group of governors sympathetic to Canada’s position (and their own political fortunes) might spearhead a legal challenge to Trump’s tariffs with encouragement and support from the Canadian government.

To be sure, any legal challenge would take time to work its way through the U.S. court system. But it will likely also take time for domestic opposition to Trump’s tariffs to gain sufficient political momentum to effect any change. Indeed, given the current composition of Congress, it’s far from clear that a Team Canada effort to rally broad anti-tariff support among U.S. politicians and business leaders would bear fruit while Trump is in office.

While direct retaliation might be emotionally satisfying to Canadians, it would likely do more economic harm than good. And while a legal challenge will not obviate the immediate economic harm Canada will suffer from Trump’s tariffs, it might help limit the ability of Trump (and any future president) to use trade policy for political leverage in our bilateral relationship. After all, there’s no guarantee that the next president will not be a Trump acolyte.

2025 Federal Election

The “Hardhat Vote” Has Embraced Pierre Poilievre

David Krayden

David Krayden

Blue collar and unionized workers are supporting Pierre Poilievre and the CPC

When President Richard Nixon won a landslide in his 1972 reelection, he did so by broadening his own personal popularity and the appeal of the Republican Party to blue collar and unionized workers. It was called the hardhat vote and many working people embraced Nixon because he seemed to be talking the same language as they were. Nixon talked about law and order and getting tough on crime; safer streets and harsher penalties for serious crime. Although unionized workers had traditionally voted for the Democratic Party and seen the Republicans as the party of the wealthy, by 1972 the Democrats had moved far to the left on social issues and were completely out of touch with average Americans who saw Democratic presidential nominee Sen. George McGovern as being soft on crime and approving of the anarchy on the streets.

It’s precisely the language that Conservative Party of Canada leader Pierre Poilievere is speaking in the 2025 federal election. As support for the New Democratic Party has collapsed throughout the election campaign, don’t think most of it is going to the Liberal Party. Poilievre has been targeting blue collar workers for years with his emphasis on the trades and talking about middle class tax cuts and safe streets. A factory or construction worker is middle class and just want an affordable lifestyle for their families. They don’t have a lot of time for the woke underbelly of the Liberals or the NDP and are increasingly reluctant to support either party because both have appealed to elites.

Listen to Karl Lovett, the president of the Local 773 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, talk about Carney corruption and why he is supporting Poilievre and the CPC in 2025.

“Mark Carney also failed to pay $5 billion in Canadian taxes by hiding his company’s assets in Bermuda above a bike shop. Hard to believe that information comes from Canada’s NDP, or at least who is left of them, because the irony is, Mark Carney has eaten all those people alive. Even the mayor of Lima has warned Canadians not to vote for Mark Carney, and why for ripping him off the poorest of the poor people in Peru. That’s who he ripped off,” Lovett said.

“Listen, there are countless other outrageous examples proving that Mark Carney doesn’t give a damn about the Canadian working man. And now, as prime minister, which he’s not, Carney is promising to put carbon tax and tariff on the auto industry. It’s another rip-off screen that’s right. We’re getting punched by Trump on one side of the border, and Carney plans to punch us on this side of the border, also pretending it’s all about climate change, and now he’s made millions off the workers’ backs. He wants more than money. He wants more power. He wants all of the power to do whatever he wants to do. Mark Carney cannot be trusted with this power. Mark Carney cannot be trusted to protect workers,” Lovett continued.

The union leader told a cheering crowd that “Mark Carney is in it for himself, and when he loses this election, you can bet Mark Carney is going to leave Canada in a New York minute. But there’s hope, there’s hope, there’s our last hope. His name is Pierre Poilievere – the .only hope for Canadian workers. You see Mark Carney fooled Justin Trudeau. We can’t let him keep fooling us.”

“Local 773, which I represent, knows Pierre Poilievre very well. We can proudly tell you that Pierre has our back. Pierre has been putting Canadian people to work and Canadian workers. First, local 773 began working with Pierre Poilievre, the Conservative Member of Parliament Chris Lewis, some years ago, when it became all too clear that the Liberal Party had zero interest in helping out workers. Upon winning the leadership of the party, Pierre made Local 773 his very first priority, he came to my union hall. Pier made the Local 773 Visitor Training Center, and he met all our workers, and he made a pledge to me; he’s not going to turn his back on us, and I believe him,” Lovett said.

Toronto Sun columnist Joe Warmington agreed with me and you can hear that entire interview, below. “Labor wants to work, and they want to, you know, build things, and they want those good, paying jobs, and that’s what Poilievre has always been about, you know.”

“He wants more power. He wants all of the power to do whatever he wants to do. Mark Carney cannot be trusted with this power. Mark Carney cannot be trusted to protect workers,”

“Again, it’s hard to know, but I always felt … and I still think that Poilievre is going to pull this off because of these reasons that you’ve raised today, I never really bought into and again, I’m just one person’s opinion, and I go on the ground. In the air, the polls are saying, I know there’s this main street poll today, maybe it’ll swing differently. But in the air, it says one thing, and on the ground, it says another thing. And that clip you just showed, that’s the ground, that’s where the workers are, that’s where the families are.”

2025 Federal Election

Poilievre will cancel Mark Carney’s new Liberal packaging law and scrap the Liberal plastic ban!

From Conservative Party Communications

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre promised today that a new Conservative government will stop Mark Carney’s proposed Liberal food tax and scrap the existing Liberal plastic ban. Poilievre will:

- Stop proposed new labelling and packaging requirements that will raise the cost of fresh produce by as much as 34% and cost the average Canadian household an additional $400 each year.

- Scrap the Liberal plastics ban, including the ban on straws, grocery bags, food containers and cutlery, and other single-use plastics, letting consumers and businesses choose what works for them.

- Protect restaurants, grocers, and low-income Canadians from one-size-fits-all packaging rules that disproportionately affect those who can least afford it.

“After the Lost Liberal Decade, many Canadians can barely afford to put food on the table. And now Mark Carney and the Liberals want to make it even harder with a new food packaging law that will raise the price of food–again,” said Poilievre. “A new Conservative government will keep food prices down by scrapping the Liberal plastic ban and stopping Carney’s new Liberal food tax.”

After a decade of out-of-control spending and massive tax increases, families are spending $800 more on food this year than they did in 2024, and food banks had to handle a record two million visits in a single month. In Montreal, 44 percent of CEGEP students are experiencing some form of food insecurity, while places like Hawkesbury, Kingston, Toronto and Mississauga have all declared food insecurity emergencies.

And food prices are still rocketing upwards, surging by 3.2% over the last year, with no end in sight. In the last month alone, food inflation increased by 1.9 percentage points—the largest monthly jump in food prices in decades.

As if this wasn’t bad enough, Liberals have made life even more expensive and inconvenient for Canadians by banning plastics – including everything from straws to bags to food packaging. The current Liberal ban on single-use plastics will cost Canadians $1.3 billion dollars over the next decade.

Now Mark Carney wants to make it worse by adding complicated and costly new food packaging rules that will drive up the price of food even more–in effect, a new Liberal food tax. Plastic food packaging makes up 1/3 of all plastic packaging in Canada. The proposed Liberal food tax will cost the average Canadian household an additional $400 each year, waste half a million tonnes of food, decrease access to imported fruit and produce, and increase food inflation. The Chemistry Industry Association of Canada has also warned that this tax will put up to 60,000 Canadians out of work.

“The Liberals’ ideological crusade against convenience has already driven up food prices and the last thing Canadians need is Mark Carney’s new food tax added directly to your grocery bill,” said Poilievre. “The choice for Canadians is clear, a fourth Liberal term that will make food even more expensive or a new Conservative government that will axe the food tax and bring back straws, grocery bags and other items, to make life more affordable and convenient for Canadians – For a Change.”

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days ago‘War On Coal Is Finally Over’: Energy Experts Say Trump Admin’s Deregulation Agenda Could Fuel Coal’s ‘Revival’

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoThe Pandemic Justice Phase Begins as Criminal Investigations Commence

-

Economy1 day ago

Economy1 day agoThe Net-Zero Dream Is Unravelling And The Consequences Are Global

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoBefore the Vote: Ask Who’s Defending Our Health

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHomebuilding in Canada stalls despite population explosion

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoThe “Hardhat Vote” Has Embraced Pierre Poilievre

-

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago

2025 Federal Election18 hours agoCarney’s Fiscal Fantasy: When the Economist Becomes More Dangerous Than the Drama Teacher

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoAddiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed