Brownstone Institute

Time to Connect the Dots

From the Brownstone Institute

By

It was an otherwise normal day in 1969 when I found the book. I was a student in Vienna for my junior year of undergrad. Like most students, I had a room with a Hausfrau, normally an elderly lady who rented out rooms to students. I shared a room on Hauslabgasse in the 5th District with an old high school classmate.

Our Hausfrau, born in 1900, was a member of the old minor Austrian Nobility. Both World Wars had been hard on her. She had served in the German Kriegsmarine occupying the Channel Islands and came back to a war-torn Vienna, but made her own way. She was a survivor. I admired her for that. But she also had a certain affection for the “good old days.”

There was an old ornate bookcase in our room. As I was examining it, I found a hidden compartment that contained a copy of Mein Kampf. It was a handsomely bound copy and obviously cherished. As I thumbed through it, I wondered how people could have been so blind. Hitler had laid out, in detail, exactly what he planned to do. And he did it. How could the world have missed it?

Perhaps we need to fast-forward to today in order to understand it. Starting in 2001, a series of simulation exercises were conducted under sponsorship of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. It began with Dark Winter dealing with a smallpox epidemic and continued with Atlantic Storm in 2005, Clade X in 2018 and culminated with Event 201 in November 2019.

This succession of planning events creates a time series of information. They are the dots that, it seems, someone or some entity is daring us to connect. Who might this be?

Well, The Center for Health Security at Hopkins, for sure. Tom Inglesby and Eric Toner are there. Inglesby even connected the events, saying “The events have a long fuse!” What exactly did he mean?

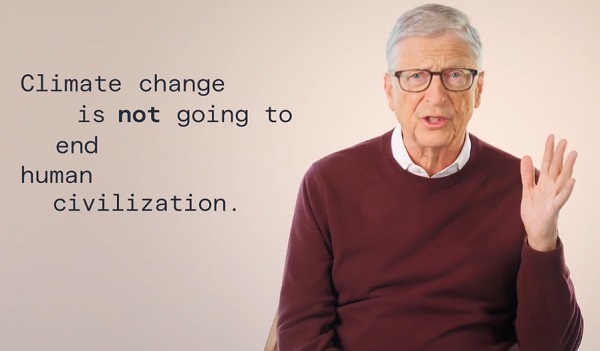

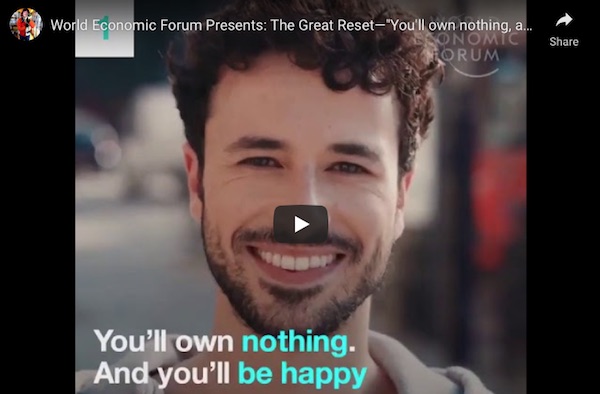

The World Economic Forum is there. They even published The Great Reset in July 2020, amazingly soon after Covid hit. This seems to be an awfully short time to get the book in print. Gates is there, with GAVI which was started even earlier, in 2000!

I can’t remember if it was Anthony Fauci or Rick Bright who articulated in the video versions of Event 201 that this would be a terrific opportunity to push vaccines. It’s all out there for everyone to see, just like in Mein Kampf!

Steven Kritz, MD, made the point in an email chat that, “For the first time ever, it was a MAN-MADE virus that caused a world-wide outbreak!” If it was man-made, it had to have a purpose. Was it simply the “sword and shield” approach stretching back to the bioweapons program of the Third Reich? Kurt Blome’s research on bioweapons was the Sword and that of Walter Schreiber on defense to those weapons was the Shield. The whole episode of their research in Nazi Germany as well as the possible transfer of this concept to The Department of Defense Research and Engineering Enterprise, is outlined in Operation Paperclip.

This is all the more interesting with the assertion by Marine Major Joseph P. Murphy to Project Veritas that supported that Sword and Shield scenario and the fact the Department of Defense controlled Operation Warp Speed.

Was it a money-making scheme of Big Pharma? Well, that is certainly plausible given the Project Veritas recordings of the Pfizer executive trying to impress his date and spilling the beans on the vaccine program. By the way, what happened to Project Veritas after all of these revelations? Did James O’Keefe finally poke the hornet’s nest too strongly? You be the judge.

So, what ties The Center for Health Security, The Department of Defense, The World Economic Forum, Big Pharma, Fauci, Gates etc. together? Is it merely a consortium of individuals and entities who realized they had a common interest, or is something else behind it all, calling the shots? Was it just a matter of us not being able to connect the dots? Or was it more like the case of my Hausfrau in Vienna more than 50 years ago, where the dots were not only connected but cherished by those few who knew the truth?

I don’t know…But it needs to be explored.

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoUS Eating Canada’s Lunch While Liberals Stall – Trump Admin Announces Record-Shattering Energy Report

-

espionage18 hours ago

espionage18 hours agoU.S. Charges Three More Chinese Scholars in Wuhan Bio-Smuggling Case, Citing Pattern of Foreign Exploitation in American Research Labs

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoU.S. Supreme Court frosty on Trump’s tariff power as world watches

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoEby should put up, shut up, or pay up

-

Justice1 day ago

Justice1 day agoCarney government lets Supreme Court decision stand despite outrage over child porn ruling

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoUN Chief Rages Against Dying Of Climate Alarm Light

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Liberal budget is a massive FAILURE: Former Liberal Cabinet Member Dan McTeague

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s budget spares tax status of Canadian churches, pro-life groups after backlash