espionage

The Scientists Who Came in From the Cold: Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory Scandal, Part I

From the C2C Journal

By Peter Shawn Taylor

In a breathless 1999 article on the opening of Canada’s top-security National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg, the Canadian Medical Association Journal described the facility as “the place where science fiction movies would be shot.” The writer was fascinated by the various containment devices and security measures designed to keep “the bad boys from the world of virology: Ebola, Marburg, Lassa” from escaping. But what if insiders could easily evade all those sci-fi features in order to help Canada’s enemies? In the first of a two-part series, Peter Shawn Taylor looks into the trove of newly-unclassified evidence regarding the role of NML scientists Xiangguo Qiu and Keding Cheng in aiding China’s expanding quest for the study – and potential military use – of those virus bad boys.

2025 Federal Election

The Anhui Convergence: Chinese United Front Network Surfaces in Australian and Canadian Elections

Revealing Beijing’s Transnational Influence Strategy

From Markham to Sydney: Tracing the CCP’s Overseas Influence Web

In the waning days of two federal election campaigns on opposite sides of the world, striking patterns of Chinese Communist Party election influence and political networking are surfacing—all tied to an increasingly scrutinized Chinese diaspora group with roots in the province of Anhui.

In Australia, Liberal candidate Scott Yung opened a business gala co-hosted by the Anhui Association of Sydney, a group officially designated by Beijing as an “overseas Chinese liaison station,” as reported by James King of 7NEWS. King identifies the Anhui group as part of a global network directed by Beijing’s United Front Work Department, an influence arm of the Chinese state that aims to shape foreign societies through elite capture and soft power.

King’s reporting is reigniting global concern over Chinese foreign interference, of the type previously exposed by The Bureau in Canada, which revealed that several Liberal Party of Canada officials, deeply involved in fundraising and election campaigning in the Greater Toronto Area, also serve as directors of an Anhui-based United Front “friendship” group with ties to a notorious underground casino operation.

That same group shares overlapping members and leadership with the Jiangsu Commerce Council of Canada (JCCC), a United Front-affiliated organization that controversially met with Liberal leadership candidate Mark Carney in January.

In the 7NEWS report, Yung is shown speaking—as a representative of Opposition Leader Peter Dutton—at a charity fundraiser co-hosted by the Anhui Association, a group previously celebrated by Beijing for supporting China’s territorial claims over Taiwan. According to King, the Anhui Association of Sydney was one of 14 overseas Chinese organizations designated in 2016 by the Anhui Foreign Affairs Office to serve as a liaison station advancing Beijing’s international strategy. Government documents show the group received AUD $200,000 annually, with instructions to “integrate overseas Chinese resources” into Anhui’s economic and social development.

Yung’s appearance on behalf of Liberal leader Dutton at an event ultimately backed by Beijing echoed mounting concerns surrounding Labor Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, his opponent in Australia’s May election.

Just weeks earlier, The Australian revealed that Albanese had dined with the vice-president of a United Front group at a Labor fundraiser—prompting sharp criticism from Liberal campaign spokesperson James Paterson, the Shadow Minister for Home Affairs. Paterson said Albanese had “all sorts of serious questions” to answer, warning that “Xi Jinping has described the United Front Work Department as the Party’s magic weapon,” according to 7NEWS.

The news organization emphasized that it “does not suggest that the Anhui Association of Sydney, its former chairman, or any of its associates have committed foreign interference or otherwise acted illegally,” noting that it is legal in Australia to act on behalf of a foreign government—so long as those actions are not covert, deceptive, or threatening.

But King’s investigation underscores a broader concern—echoed in reporting from Canada and New Zealand—that Chinese diaspora organizations, operating through the CCP’s United Front system, are being strategically leveraged by Beijing’s intelligence and foreign policy arms to fund major political parties across liberal democracies, influence parliamentary policy in line with CCP objectives, and shape leadership pipelines, including the placement of favored candidates and bureaucrats into sensitive government roles.

This strategy finds a near-identical expression in Canada, where intelligence officials in Toronto have long monitored a related organization: the Hefei Friendship Association, which maintains structural ties—via Anhui province United Front entities—to the Sydney group. Founded prior to 2012 by alleged underground casino operator Wei Wei, the Hefei group is based in Markham, Ontario, and plays a central role in an ongoing CSIS investigation into foreign interference.

Documents and sources reviewed by The Bureau confirm that the Hefei Friendship Association shares leadership with the Jiangsu Commerce Council of Canada (JCCC), a group openly tied to provincial-level United Front Work Department officials in Jiangsu, the province adjacent to Anhui. In earlier reporting on the Markham illegal casino network—widely referred to as the 5 Decourcy case—The Bureau cited an investigator with direct knowledge of what intelligence sources describe as a botched national security probe. The inquiry focused on Canadian politicians attending the casino alongside Chinese community leaders affiliated with Beijing’s overseas influence operations.

One legal source close to the file summarized the issue bluntly: “The national security and intelligence apparatus of this country is ineffective and broken. I’m in disbelief at the lack of ethics and enforcement around government officials.”

According to national security sources, the 5 Decourcy mansion-casino is viewed as just one visible node in a transnational system stretching from Toronto to Vancouver—a system that includes organized crime networks, unregistered lobbying, and foreign-aligned political financing. A CSIS source confirmed that the operation—which allegedly entertained politicians—fits Beijing’s model of leveraging transnational organized crime to advance political goals abroad. That model, they noted, closely mirrors warnings from Australia’s ASIO, which has linked similar figures in the real estate sector to major donations to all three of Australia’s major political parties, including those led by Dutton and Albanese.

Further investigation by The Bureau reveals deeper overlap between the Anhui United Front networks and the Jiangsu group that met with Mark Carney in January. Among the co-directors of the Anhui United Front group—pictured in meetings and named in documents alongside Wei Wei—is a prominent Markham-area Liberal riding official, involved in fundraising for Justin Trudeau. That same individual holds a leadership role with the JCCC, which met with Carney in a meeting that was initially denied, then downplayed.

Images reviewed by The Bureau show Wei Wei seated beside a Liberal Party politician and community organizer at a private association gathering, while another Liberal official with ties to the JCCC stands behind them. A second photo, taken inside Wei Wei’s residence, shows additional Liberal figures affiliated with Anhui- and Jiangsu-linked United Front community groups.

Documents obtained by King show that the Anhui Association of Sydney was tasked to “strive to closely integrate overseas Chinese affairs with the province’s economic and social development,” according to the director of the Anhui Foreign Affairs and Overseas Chinese Affairs Office. The Bureau has reviewed similar language in Canadian documents signed by JCCC leaders, including the Hefei Friendship Association director tied to Wei Wei—reinforcing that both the Canadian and Australian networks appear to operate under direct, formal tasking from provincial CCP entities.

As these revelations now resurface in the middle of Canada’s federal election campaign, they echo with findings in New Zealand. The 2018 political implosion involving MP Jami-Lee Ross offered a cautionary tale of how foreign-aligned networks can entangle party finances, diaspora outreach, and internal leadership struggles.

Ross, once a rising star in New Zealand’s National Party, secretly recorded party leader Simon Bridges discussing a controversial $100,000 donation, which Ross alleged was tied to Chinese business interests. The scandal shattered National’s leadership and exposed vulnerabilities in its campaign finance ecosystem. In an interview with Stuff, Ross described how his relationships with Chinese community leaders, while partly grounded in legitimate social engagement, also became channels for Beijing’s political aims.

“These [Chinese] associations, which bring together the expat Chinese community, they probably do have a good social function in many regards,” Ross said. “But there’s a wider agenda. And the wider agenda is influencing political parties. And by influencing political parties, you end up influencing the government of the day. What average New Zealander out there can get the leadership of a political party to go to their home for dinner? What average person out there could just click their fingers and command 10 MPs to come to their event? Most people can’t. Money buys their influence.”

2025 Federal Election

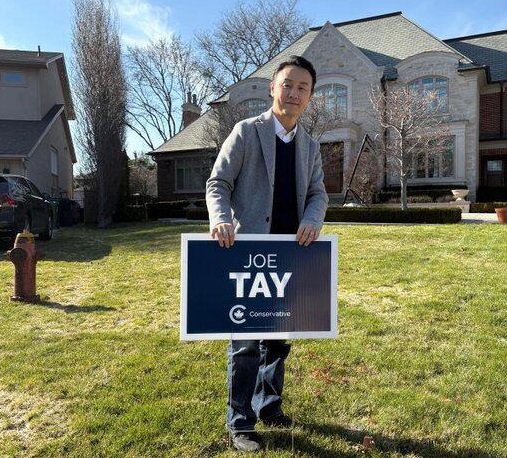

CHINESE ELECTION THREAT WARNING: Conservative Candidate Joe Tay Paused Public Campaign

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

Now, with six days until Canada’s pivotal vote—in an election likely to be decided across key Toronto battleground ridings—it appears that Tay’s ability to reach voters in person has also been downgraded.

Joseph Tay, the Conservative candidate identified by federal authorities as the target of aggressive Chinese election interference operations, paused in-person campaigning yesterday following advice from federal police, The Bureau has learned.

Two sources with awareness of the matter said the move came after the SITE Task Force—Canada’s election-threat monitor—confirmed that Tay is the subject of a highly coordinated transnational repression operation tied to the People’s Republic of China. The campaign seeks not only to discredit Tay, but to suppress the ability of Chinese Canadian voters to access his campaign messages online, via cyber operations conducted by Beijing’s internet authorities.

Now, with six days until Canada’s pivotal vote—in an election likely to be decided across key Toronto battleground ridings—it appears that Tay’s ability to reach voters in person has also been downgraded.

Tay, a journalist and pro-democracy advocate born in Hong Kong, is running for the Conservative Party in the Don Valley North riding. Federal intelligence sources have confirmed that his political activities have made him a top target for Beijing-linked online attacks and digital suppression efforts in the lead-up to next week’s federal election.

Tay’s need to suspend door-knocking yesterday in Don Valley North echoes concerns raised in a neighbouring riding during the 2021 federal campaign—where The Bureau previously uncovered allegations of Chinese government intimidation and targeting of voters and a Conservative incumbent. According to senior Conservative sources, Chinese agents attempted to intimidate voters and monitor the door-to-door campaign of then-incumbent MP Bob Saroya in Markham–Unionville.

Paul Chiang, a former police officer who unseated Saroya in 2021, stepped down as a candidate earlier this month after the RCMP confirmed it was reviewing remarks he made to Chinese-language media in January. During that event, Chiang reportedly said the election of Tay—a Canadian citizen wanted under Hong Kong’s National Security Law—to Parliament would cause “great controversy” for Canada. He then suggested, in a remark reported by a Chinese-language newspaper, that Tay could be turned over to the Toronto Chinese Consulate to claim the $180,000 bounty on his head. Chiang apologized after the comments were reported, claiming his remarks had been made in jest.

In a briefing yesterday, SITE disclosed that Tay has been the victim of similarly threatening online messaging.

One Facebook post circulated widely in Chinese-language forums declared: “Wanted for national security reasons, Joe Tay looks to run for a seat in the Canadian Parliament; a successful bid would be a disaster. Is Canada about to become a fugitive’s paradise?”

Tay, a former Hong Kong broadcaster whose independent reporting from Canada has drawn retaliation from Beijing, rejected Chiang’s apology in March, calling the remarks “the tradecraft of the Chinese Communist Party.” He added: “They are not just aimed at me; they are intended to send a chilling signal to the entire community to force compliance with Beijing’s political goals.” His concerns were echoed by NGOs and human rights organizations, which condemned Chiang’s comments as an endorsement of transnational repression.

In light of the RCMP’s reported advice to Tay this week, the challenges faced by Conservative candidates attempting to meet Chinese Canadian voters in Greater Toronto appear to reflect a broader and troubling pattern.

According to multiple senior figures from Erin O’Toole’s 2021 Conservative campaign—who spoke on condition of anonymity—O’Toole’s team was briefed by Canadian intelligence officials that Chinese government actors were surveilling then-incumbent MP Bob Saroya during the campaign. One source recalled, “There were Chinese officials following Bob Saroya around,” adding that “CSIS literally said repeatedly that this was ‘coordinated and alarming.’”

When asked to comment, O’Toole—who stepped down as leader following the Conservative’s 2021 loss—acknowledged awareness of voter intimidation reports but declined to confirm whether CSIS had briefed his team directly on the matter.

“Our candidate Bob Saroya was a hardworking MP who won against the Liberal wave in 2015,” O’Toole wrote in a statement. “He won in 2019 as well, but thousands of votes from the Chinese Canadian community stayed home in 2021. We heard reports of intimidation of voters. We also know the Consul General from China took particular interest in the riding and made strange comments to Mr. Saroya ahead of the election. It was always in the top three of the eight or nine ridings that I believe were flipped due to foreign interference.”

SITE’s new findings on Tay’s campaign in Don Valley North reinforce those long-standing concerns. “This is not about a single post going viral,” SITE warned. “It is a series of deliberate and persistent activity across multiple platforms—a coordinated attempt to distort visibility, suppress legitimate discourse, and shape the information environment for Chinese-speaking voters in Canada.”

The Task Force said the most recent wave of coordinated online activity occurred in late March, when a Facebook post appeared denigrating Tay’s candidacy. “Posts like this one appeared en masse on March 24 and 25 and appear to be timed for the Conservative Party’s announcement that Tay would run in Don Valley North,” SITE stated in briefing materials.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoTrump Has Driven Canadians Crazy. This Is How Crazy.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoThe Anhui Convergence: Chinese United Front Network Surfaces in Australian and Canadian Elections

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoHyundai moves SUV production to U.S.

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoAs PM Poilievre would cancel summer holidays for MP’s so Ottawa can finally get back to work

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoPoilievre Campaigning To Build A Canadian Economic Fortress

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPolls say Canadians will give Trump what he wants, a Carney victory.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCarney Liberals pledge to follow ‘gender-based goals analysis’ in all government policy

No happy endings here:

No happy endings here:  Internationally-renowned virologist Xiangguo Qiu (top left) and her husband, biologist Keding Cheng (top right), both worked at Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) until they were escorted off the premises in July 2019 for what was initially described as an “administrative matter”. (Sources of photos: (top left)

Internationally-renowned virologist Xiangguo Qiu (top left) and her husband, biologist Keding Cheng (top right), both worked at Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) until they were escorted off the premises in July 2019 for what was initially described as an “administrative matter”. (Sources of photos: (top left)

A look behind the curtain: Made public in February 2024, the 623-page collection of formerly-classified documents includes (from left to right) a third-party investigation into Qiu and Cheng, secret “Canadian Eyes Only” reports from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the pair’s own response to accusations made against them.

A look behind the curtain: Made public in February 2024, the 623-page collection of formerly-classified documents includes (from left to right) a third-party investigation into Qiu and Cheng, secret “Canadian Eyes Only” reports from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the pair’s own response to accusations made against them. “For the RCMP to go into the lab and remove the scientists…it had to be more than a personnel matter,” says John Williamson, a Conservative MP from New Brunswick. Williamson was the only Conservative member on the ad hoc committee of four MPs given access to the entire file of classified documents ahead of their public release. (Source of photo:

“For the RCMP to go into the lab and remove the scientists…it had to be more than a personnel matter,” says John Williamson, a Conservative MP from New Brunswick. Williamson was the only Conservative member on the ad hoc committee of four MPs given access to the entire file of classified documents ahead of their public release. (Source of photo:  “Scientists need to do what scientists do”: Initial investigations by the PHAC and CSIS revealed that Qiu and Cheng shared a surprisingly carefree attitude towards security rules, despite working in Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Laboratory. Shown, Qiu at work in her Winnipeg lab. (Source of photo:

“Scientists need to do what scientists do”: Initial investigations by the PHAC and CSIS revealed that Qiu and Cheng shared a surprisingly carefree attitude towards security rules, despite working in Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Laboratory. Shown, Qiu at work in her Winnipeg lab. (Source of photo:  The plot unfolds: The first CSIS investigation revealed that Qiu had conducted joint research with scientists at China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences (shown). Despite this worrisome connection, CSIS was initially reluctant to categorize Qiu as a security risk. (Source of photo:

The plot unfolds: The first CSIS investigation revealed that Qiu had conducted joint research with scientists at China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences (shown). Despite this worrisome connection, CSIS was initially reluctant to categorize Qiu as a security risk. (Source of photo:  CSIS reopened its investigation into Qiu and Cheng after “newly discovered information” cast doubt on Qiu’s loyalty to Canada due to her “close and clandestine relationships with a variety of entities of the People’s Republic of China.”

CSIS reopened its investigation into Qiu and Cheng after “newly discovered information” cast doubt on Qiu’s loyalty to Canada due to her “close and clandestine relationships with a variety of entities of the People’s Republic of China.” A talent for espionage: According to the FBI, China’s many “talent” programs usually involve “undisclosed and illegal transfers of information, technology, or intellectual property” from western countries to China.

A talent for espionage: According to the FBI, China’s many “talent” programs usually involve “undisclosed and illegal transfers of information, technology, or intellectual property” from western countries to China. “The only highly experienced Chinese expert available”: CSIS uncovered documents revealing that Qiu was considered essential to the research ambitions of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (shown), an institution with close ties to the Chinese military and infamous for its proximity, and likely connection, to the initial outbreak of Covid-19. (Source of photo: AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

“The only highly experienced Chinese expert available”: CSIS uncovered documents revealing that Qiu was considered essential to the research ambitions of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (shown), an institution with close ties to the Chinese military and infamous for its proximity, and likely connection, to the initial outbreak of Covid-19. (Source of photo: AP Photo/Ng Han Guan) Bosom buddies: Shi Zhengli, WIV’s deputy-director and often referred to as “bat-woman” (left), and Major-General Chen Wei, China’s “top biowarfare expert” (right), frequently collaborated with Qiu during her time at the NML. (Source of left photo: Chinatopix via AP, File)

Bosom buddies: Shi Zhengli, WIV’s deputy-director and often referred to as “bat-woman” (left), and Major-General Chen Wei, China’s “top biowarfare expert” (right), frequently collaborated with Qiu during her time at the NML. (Source of left photo: Chinatopix via AP, File) Scrubbed clean: Qiu held multiple positions at Chinese universities as early as April 2016, but hid these facts from PHAC management and lied about them in her initial interview with CSIS.

Scrubbed clean: Qiu held multiple positions at Chinese universities as early as April 2016, but hid these facts from PHAC management and lied about them in her initial interview with CSIS. “There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power”: Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe raised the alarm about China’s biowarfare ambitions in 2020, noting that China has “conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities.” (Source of photo:

“There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power”: Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe raised the alarm about China’s biowarfare ambitions in 2020, noting that China has “conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities.” (Source of photo:  Spies happily ever-after: According to a Globe and Mail investigation, Qiu and Cheng currently live in China and are each employed in their chosen fields. Curiously, they appear to have adopted new names – Sandra Chiu and Kaiting Cheng.

Spies happily ever-after: According to a Globe and Mail investigation, Qiu and Cheng currently live in China and are each employed in their chosen fields. Curiously, they appear to have adopted new names – Sandra Chiu and Kaiting Cheng.