Gerry Feehan

The Olympic Peninsula by Gerry Feehan

The Olympic Peninsula

On November 8, 2021 the land border to the USA opened again!

I love America. The weather is great, the scenery fantastic and the people hospitable. But the US has a problem: guns. We hadn’t been in the country twenty-four hours before we found ourselves staring down the barrel of a sheriff’s assault rifle—at a campground. After a lovely morning hike overlooking Washington State’s San Juan Islands we were skipping happily back to our site when a camouflaged sniper waived us to the ground. We crawled toward our motorhome—which had been commandeered for police cover.

Four muzzles were aimed from behind our RV toward an adjacent trailer. I heard the words, “domestic…choking…firearms,” crackle over the commander’s radio.

What would spark gunplay in a campground? Had someone made the campfire coffee too strong? Were the marshmallows charred? We never did find out. The police escorted us out the park gate—and we returned blithely to the meandering highway. We monitored the radio to ascertain the cause of the fireworks but learned nothing. Perhaps a nearby school massacre overshadowed the shootout at the OK Campground.

But after this first hiccup our Washington State experience was gun-free, peaceful and marked entirely by friendly encounters. Everywhere we were greeted by kind, attentive folk with a genuine interest in how their Canadian brethren were faring.

“Do you think we can get through the south shore road to Grave’s Creek campground tomorrow?” I asked.

The Rain Forest Resort sits along the shores of Lake Quinault in Washington’s beautiful Olympic Peninsula. The narrow road to the resort passes through a cathedral of towering Douglas fir, Sitka spruce and red cedar. The largest in the world of each of these species grows within spitting distance of the lake—and the quaint village provides access to one of the world’s great temperate rain forests.

bull Roosevelt elk

The Morrison family has owned this little jewel of a resort—and everything else in town (including the coin laundry and paid showers)—since the 1960’s. The town gets four meters of rain a year. The camp store sells a lot of quarters to soggy travellers trying vainly to dry hiking gear—while thawing chilled bones in a hot shower. In the 48 hours we were hunkered down, hiding from a brutal storm, 15 cm of rain bombarded the Rain Forest Resort campground. The lake rose and water began lapping up the wheels of our RV. There was a knock on the door. Don Morrison kept both feet safely on the running board of his old pickup as he pointed to the half-submerged post to which our electrical cord was plugged.

“We’d better get you to higher ground.”

“Neither rain, nor…”

We evacuated uphill, and plugged in at the local post office building (which, naturally, is owned by the Morrisons). So neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night can stop the post office from delivering—either the mail or electricity to a stranded RV. That evening, over happy-hour cocktails at the Salmon House Restaurant (which is owned by… guess who?), Don and his brother traded war stories about just how high the water can get.

“Remember ’94?” said Don. “That was the year we put the cabins up on stilts.”

“Yeah, but what about the summer of ’79 when we lost power for ten days?” responded his brother. “We threw out three freezers of elk, salmon and frozen clams.”

While they happily reminisced about past disasters Florence and I stared out the window at the non-stop deluge.

“Do you think we can get through the south shore road to Grave’s Creek campground tomorrow?” I asked.

“Hard to say,” said Don. “You’ll have to drive through Sasquatch valley, which can be slippery and there could be some trees down. There’s always the long way round, over the north shore.” He pointed across Lake Quinault.

Optimistically we struck out in the morning on the south route. On a narrow stretch ten kilometers down a muddy gravel road we rounded a steep curve. I slammed on the brakes. Fifteen or twenty massive, freshly fallen trunks lay across the road. A swath of ancient conifers had toppled, domino-like, rendering the route impassable. The locals call this a blow-down event. Where the trees had formerly stood, a narrow window of light shone brightly through the dark canopy, illuminating the carnage.

Now what?

We backed up for almost a kilometer before finding a safe spot to turn around. Intent on getting to the remote rain forest at Graves Creek, we drove around the lake and tested the equally tricky north shore road. We arrived at the secluded campground as darkness descended. The rain had abated from gale-force to storm-watch. In the morning we geared up for a wet tromp. An hour or so in we met Michael Butler on a remote hiking trail that had converted itself into a medium-sized creek. The sky was pouring buckets. The only people stupid enough to brave the elements were Mike and the Feehans. We were headed upstream and he down.

Banana slug meets mushroom (inset orange jelly fungus)

“It gets quite a bit worse up there,” he remarked, glancing over his shoulder, soaked to the bone and smiling. Water was running out the toes of his hiking boots. A banana slug floated by. We abandoned ship and turned back, down-trail with Mike.

He was from Long Island New York, sleeping in his car and subsisting on cold rice. His eyes were red. “I didn’t sleep much last night,” he said. “I have mice—two of them.”

We invited him for dinner chez Feehan for Florence’s famous Friday night homemade pizza. He acquiesced without an arm-twisting. Mike is a lanky kid, but like most twenty-two year olds can really pack away the groceries—particularly when served up in a dry, rodent-free establishment. Mike was travelling the entire “lower 48” carrying his grandparent’s ashes, leaving a trace in every State. He’d been on the road for six months but still had a bunch of places in which he’d not yet spilt his relatives’ remains. He’d taken a sabbatical from medical school to nurse his grandparents at the end of their lives. After they died he quit school entirely, disgusted with the insurance companies and the medical system in general. Did I say the US has a problem with guns? Apparently it also has health-care issues.

Florence and Mike have different perspectives on life.

When we left in the morning, Mike was still sawing logs, mouth agape, driver’s seat splayed back. Through the foggy windshield I spied a mousetrap, set for action. We quietly left a note under his wiper:

“I can see a pair of mice by your dashboard lights.”

As we drove out, through an ancient grove of large-leaf maple trees draped in wet club moss, the rain stopped. For the first time in days the sun began to shine.

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management for sponsoring this series. Click on the ads and learn more about this long-term local business.

We will travel again but in the meantime, enjoy Gerry’s ‘Buddy Trip to Ireland’

Gerry Feehan

Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a marvel of ancient and modern engineering

I love looking out the window of an airplane at the earth far below, seeing where coast meets water or observing the eroded remains of some ancient formation in the changing light. Alas, the grimy desert sand hadn’t been cleaned from the windows of our EgyptAir jet, so we couldn’t see a thing as we flew over Lake Nasser en route to Abu Simbel. I was hopeful that this lack of attention to detail would not extend to other minor maintenance items, such as ensuring the cabin was pressurized or the fuel tank full.

We had just spent a week on a dahabiya sailboat cruising the Nile River, and after disembarking at Aswan, were headed further south to see one of Egypt’s great

monuments. There are a couple of ways to get to Abu Simbel from Aswan. You can ride a bus for 4 hours through the scorched Sahara Desert, or you can take a plane for the short 45-minute flight.

Opaque windows notwithstanding, I was glad we had chosen travel by air. Abu Simbel is spectacular, but there’s really not much to see except the monument itself and a small adjacent museum. So most tourists, us included, make the return trip in a day. And fortunately we had Sayed Mansour, an Egyptologist, on board. Sayed was there to explain all and clear our pained expressions.

Although it was early November, the intense Nubian sun was almost directly overhead, so Sayed led us to a quiet, shady spot where he began our introduction to

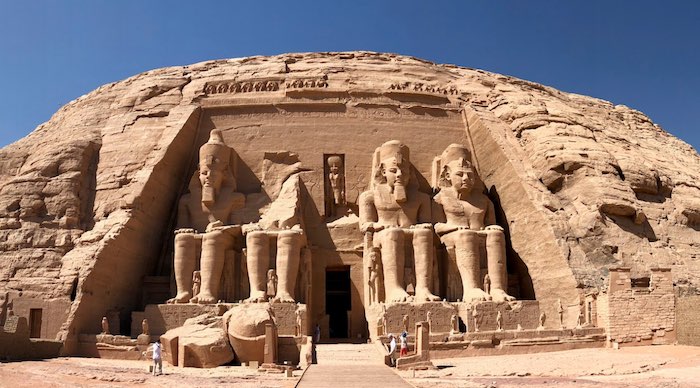

Egyptian history. Abu Simbel is a marvel of engineering — both modern and ancient. The temples were constructed during the reign of Ramses II. Carved from solid rock in a sandstone cliff overlooking the mighty river, these massive twin temples stood sentinel at a menacing bend in the Nile — and served as an intimidating obstacle to would-be invaders — for over 3000 years. But eventually Abu Simbel fell into disuse and succumbed to the inevitable, unrelenting Sahara. The site was nearly swallowed by sand when it was “rediscovered” by European adventurers in the early 19 th century. After years of excavation and restoration, the monuments resumed their original glory.

Then, in the 1960’s, Egyptian president Abdel Nasser decided to construct a new “High Dam” at Aswan. Doing so would create the largest man-made lake in the

world, 5250 sq km of backed-up Nile River. This ambitious project would bring economic benefit to parched Egypt, control the unpredictable annual Nile flood and also supply hydroelectric power to a poor, under-developed country. With the dam, the lights would go on in most Egyptian villages for the first time. But there were also a couple of drawbacks, which were conveniently swept under the water carpet by the government. The new reservoir would displace the local Nubian population whose forbearers had farmed the fertile banks of the Nile River for millennia. And many of Egypt’s greatest monuments and tombs would be forever submerged beneath the deep new basin — Abu Simbel included. But the government proceeded with the dam, monuments be damned.

Only after the water began to rise did an international team of archaeologists, scientists — and an army of labourers — begin the process of preserving these

colossal wonders. In an urgent race against the rising tide, the temples of Abu Simbel were surgically sliced into gigantic pieces, transported up the bank to safety and reassembled. The process was remarkable, a feat of engineering genius. And today the twin edifices, honouring Ramses and his wife Nefertari remain, gigantic, imperious and intact. But instead of overlooking a daunting corner of the Nile, this UNESCO World Heritage site now stands guard over a vast shimmering lake.

Sayed led us into the courtyard from our shady refuge and pointed to the four giant Colossi that decorate the exterior façade of the main temple. These statues of

Ramses were sculpted directly from Nile bedrock and sat stonily observing the river for 33 centuries. It was brutally hot under the direct sun. I was grateful for the new hat I had just acquired from a gullible street merchant. Poor fellow didn’t know what hit him. He started out demanding $40, but after a prolonged and brilliant negotiating session, I closed the deal for a trifling $36. It was difficult to hold back a grin as I sauntered away sporting my new fedora — although the thing did fall apart a couple of days later.

Sayed walked us toward the sacred heart of the shrine and lowered his voice. Like all Egyptians, Sayed’s native tongue is Arabic. But, oddly, his otherwise perfect English betrayed a slight cockney accent. (Sayed later disclosed that he had spent a couple of years working in an East London parts factory.) He showed us how the great hypostyle hall of the temple’s interior is supported by eight enormous pillars honouring Osiris, god of the underworld.

Exploring the inner temple

Nefertari

Sayed then left us to our devices. There were no other tourists. We had this incredible place to ourselves. In the dim light, we scampered amongst the sculptures

and sarcophagi, wandering, hiding and giggling as we explored the interior and its side chambers. At the far end lay the “the holiest of holies” a room whose walls were adorned with ornate carvings honouring the great Pharaoh’s victories — and offering tribute to the gods that made Ramses’ triumphs possible.

Exterior photographs of Abu Simbel are permitted, but pictures from within the sanctuary are verboten — a rule strictly enforced by the vigilant temple guardians — unless you offer a little baksheesh… in which case you can snap away to your heart’s content. Palms suitably greased, the caretakers are happy to pose with you in front of a hidden hieroglyph or a forbidden frieze, notwithstanding the stern glare of Ramses looking down from above.

A little baksheesh is key to holding the key

After our brief few hours at Abu Simbel, we hopped back on the plane. The panes weren’t any clearer but, acknowledging that there really wasn’t much to see in the Sahara — and that dirty airplane windows are not really a bona fide safety concern — I took time on the short flight to relax and bone up on Ramses the Great, whose mummified body awaited us at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Exodus Travel skilfully handled every detail of our Egypt adventure: www.exodustravels.com/

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management for sponsoring this series. Click on the ads and learn more about this long-term local business.

Gerry Feehan

Cairo – Al-Qahirah

The Pyramids of Giza

The first thing one notices upon arrival in Egypt is the intense level of security. I was screened once, scanned twice and patted down thrice between the time we landed at the airport and when we finally stepped out into the muggy Cairo evening. At our hotel the scrutiny continued with one last investigation of our luggage in the lobby. Although Egyptian security is abundant in quantity, the quality is questionable. The airport x-ray fellow, examining the egg shaker in my ukulele case, sternly demanded, “This, this, open this.” When I innocently shook the little plastic thing to demonstrate its impermeability he recoiled in horror, but then observed it with fascination and called over his supervisor. Thus began an animated, impromptu percussion session. As for the ukulele, it was confiscated at hotel check-in and imprisoned in the coat check for the duration of our Cairo stay. The reasons proffered for the seizure of this innocuous little instrument ranged from “safety purposes” to “forbidden entertainment”. When, after a very long day, we finally collapsed exhausted into bed, I was shaken — but did not stir.

Al-Qahirah has 20 million inhabitants, all squeezed into a thin green strip along the Nile River. Fading infrastructure and an exponential growth in vehicles have contributed to its well-deserved reputation as one of the world’s most traffic-congested cities. The 20km trip from our hotel in the city center, to the Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza across the river, took nearly two hours. The driver smiled, “Very good, not rush hour.”

Our entrance fee for the Giza site was prepaid but we elected to fork out the extra Egyptian pounds to gain access to the interior of the Great Pyramid. Despite the up-charge — and the narrow, dark, claustrophobic climb – the reward, standing in Cheop’s eternal resting place, a crypt hidden deep inside the pyramid, was well worth it. We also chose to stay after sunset, dine al fresco in the warm Egyptian evening, and watch the celebrated ‘sound and light’ performance. The show was good. The food was marginal. Our waiter’s name was Fahid. Like many devout Muslim men, he sported a zabiba, or prayer bump, a callus developed on the forehead from years of prostration. Unfortunately throughout the event Fahid hovered over us, attentive to the point of irritation, blocking our view of the spectacle while constantly snapping fingers at his nervous underlings. The ‘son et lumière’ show was a little corny, but it’s pretty cool to see a trio of 4500-year-old pyramids – and the adjoining Great Sphinx — illuminated by 21 st century technology.

The Great Sphinx

Giza at nightThe next night our group of six Canucks attended an Egyptian cooking class. Our ebullient hostess was Anhar, (‘the River’ in Arabic). Encouraged by her contagious enthusiasm, we whipped up a nice tabouli salad, spicy chicken orzo soup and eggplant moussaka. We finished up with homemade baklava. Throughout the evening, Anhar quizzed us about the ingredients, the herbs and spices, their origins and proper method of preparation. Anyone who answered correctly was rewarded with her approving nod and a polite clap. Soon a contest ensued. Incorrect answers resulted in a loud communal ‘bzzzt’ — like the sound ending a hockey game. It’s not polite to blow one’s own horn, but the Feehan contingent acquitted themselves quite nicely. If I still had her email, Anhar could confirm this.

Cairo was not the highlight of our three-week Egyptian holiday, but a visit to the capital is mandatory. First there’s the incredible Pyramids. But as well there’s the Egyptian Museum that houses the world’s largest collection of Pharaonic antiquities including the golden finery of King Tutankhamen and the mummified remains of Ramses the Great. Ramses’ hair is rust coloured and thinning a little, but overall he looks pretty good for a guy entering his 34 th century.

Ramses the Great

Then there’s Khan el-Khalili, the old souk or Islamic bazaar. We strolled its ancient streets and narrow meandering alleyways, continually set upon by indefatigable street hawkers. “La shukraan, no thanks,” we repeated ineffectually a thousand times. The souk’s cafes were jammed. A soccer match was on. The ‘beautiful game’ is huge in Egypt. Men and women sat, eyes glued to the screen, sipping tea and inhaling hubbly bubbly.

The Old Souk Bazaar

Selfies, Souk style

An aside. When traveling in Egypt, be sure to carry some loose change for the hammam (el baño for those of you who’ve been to Mexico). At every hotel, restaurant, museum and temple — even at the humblest rural commode — an attendant vigilantly guards the lavatory. And have small bills for the requisite baksheesh. You’re not getting change.

After our evening in the souk we had an early call. Our guide Sayed Mansour met us at 6am in the hotel lobby. “Yella, yella. Hurry, let’s go,” he said. “Ana mish bahasir – I’m not joking.” “Afwan,” we said. “No problem,” and jumped into the van. As we pulled away from the curb Sayed began the day’s tutorial, reciting a poem by Percy Blythe Shelly:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

And we were off, through the desert, to Alexandria. Founded by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, Egypt’s ancient capital was built on the Nile delta, where the world’s longest river meets the Mediterranean Sea. The day was a bit of a bust. The city was once renowned for its magnificent library and the famed Lighthouse of Alexandria. But the former burnt down shortly after Christ was born and the latter — one of the original seven wonders of the ancient world – toppled into the sea a thousand years ago. Absent some interesting architecture, a nice view of the sea from the Citadel — and Sayed’s entertaining commentary — Alexandria wasn’t really worth the long day trip. Besides, we needed to get back to Cairo and pack our swimwear. Sharm el Sheikh and the warm waters of the Red Sea were next up on the Egyptian agenda.

Gerry with some Egyptian admirers

Exodus Travel skilfully handled every detail of our trip: www.exodustravels.com And, if you’re thinking of visiting Egypt, I can suggest a nice itinerary. No sense reinventing the pyramid: [email protected]

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management for sponsoring this series. Click on the ads and learn more about this long-term local business.

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoTrump Executive Orders ensure ‘Beautiful Clean’ Affordable Coal will continue to bolster US energy grid

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoBREAKING from THE BUREAU: Pro-Beijing Group That Pushed Erin O’Toole’s Exit Warns Chinese Canadians to “Vote Carefully”

-

Business2 days ago

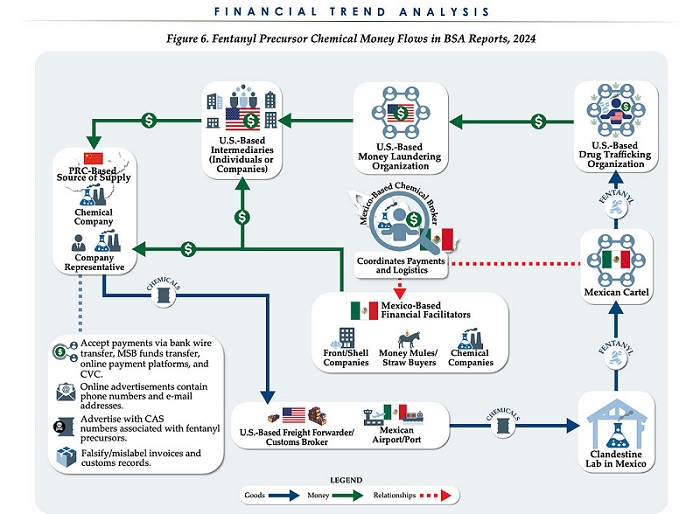

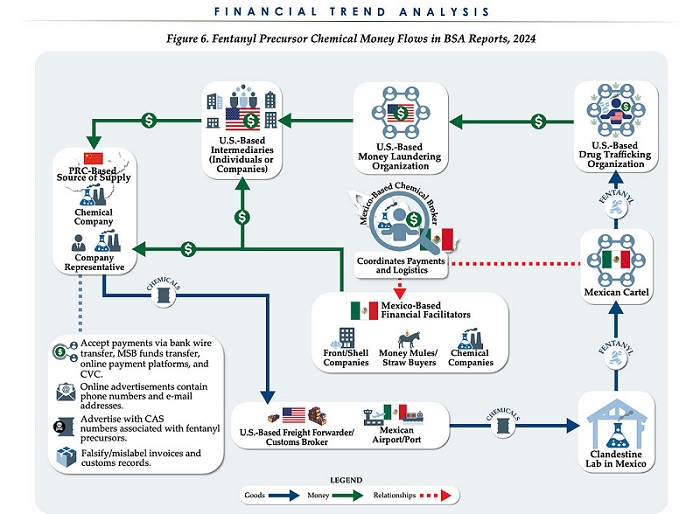

Business2 days agoChina, Mexico, Canada Flagged in $1.4 Billion Fentanyl Trade by U.S. Financial Watchdog

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTamara Lich and Chris Barber trial update: The Longest Mischief Trial of All Time continues..

-

Energy1 day ago

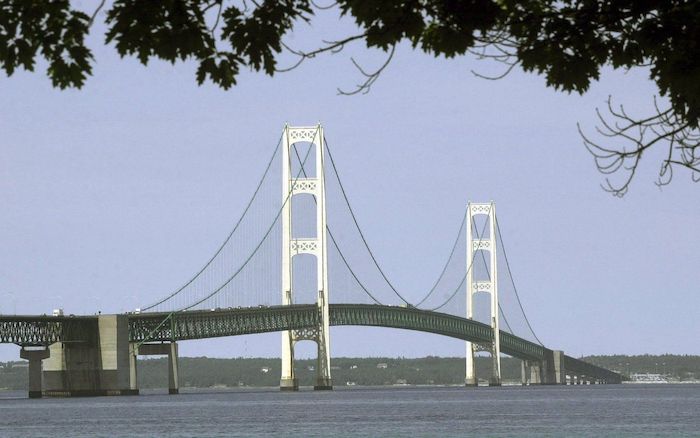

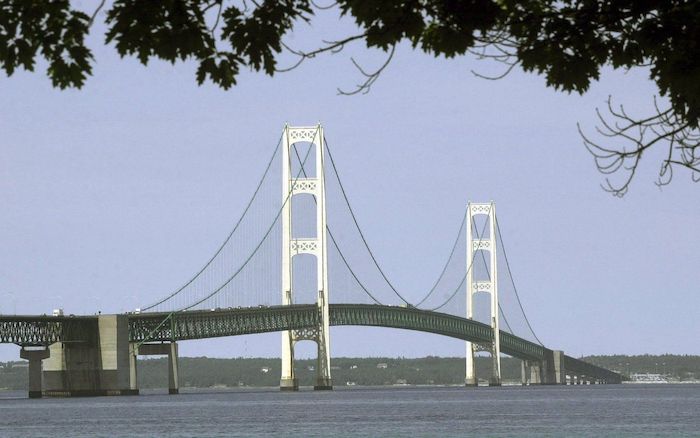

Energy1 day agoStraits of Mackinac Tunnel for Line 5 Pipeline to get “accelerated review”: US Army Corps of Engineers

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoAllegations of ethical misconduct by the Prime Minister and Government of Canada during the current federal election campaign

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoPRC-Linked Disinformation Claims Conservatives Threaten Chinese Diaspora Interests, Take Aim at PM Carney’s Debate Remark

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoDOJ Releases Dossier Of Deported Maryland Man’s Alleged MS-13 Gang Ties