Crime

The Bureau Exclusive: The US Government Fentanyl Case Against China, Canada, Mexico

Canadian federal police recently busted a massive fentanyl lab with evident links to Mexico and Chinese crime networks in British Columbia.

Canada increasingly exploited by China for fentanyl production and export, with over 350 gang networks operating, Canadian Security Intelligence Service reports

As the Trump Administration gears up to launch a comprehensive war on fentanyl trafficking, production, and money laundering, the United States is setting its sights on three nations it holds accountable: China, Mexico, and Canada. In an exclusive investigation, The Bureau delves into the U.S. government’s case, tracking the history of fentanyl networks infiltrating North America since the early 1990s, with over 350 organized crime groups now using Canada as a fentanyl production, transshipment, and export powerhouse linked to China, according to Canadian intelligence.

Drawing on documents and senior Drug Enforcement Administration sources—including a confidential brief from an enforcement and intelligence expert who spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter—we unravel the evolution of this clandestine trade and its far-reaching implications, leading to the standoff that will ultimately pit President Donald Trump against China’s Xi Jinping.

In a post Tuesday morning that followed his stunning threat of 25 percent tariffs against Mexico and Canada, President Trump wrote:

“I have had many talks with China about the massive amounts of drugs, in particular fentanyl, being sent into the United States—but to no avail. Representatives of China told me that they would institute their maximum penalty, that of death, for any drug dealers caught doing this but, unfortunately, they never followed through, and drugs are pouring into our country, mostly through Mexico, at levels never seen before.”

While Trump’s announcements are harsh and jarring, the sentiment that China is either lacking motivation to crack down on profitable chemical precursor sales—or even intentionally leveraging fentanyl against North America—extends throughout Washington today.

And there is no debate on where the opioid overdose crisis originates.

At a November 8 symposium hosted by Georgetown University’s Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues, David Luckey, a defense researcher at RAND Corporation, said: “The production, distribution, and use of illegally manufactured fentanyl should be thought of as an ecosystem, and the People’s Republic of China is at the beginning of the global fentanyl supply chain.”

The Bureau’s sources come from the hardline geopolitical camp on this matter. They believe Beijing is attempting to destabilize the U.S. with fentanyl, in what is technically called hybrid warfare. They explained how Canada and Mexico support the networks emanating from China’s economy and political leadership. In Canada, the story is about financial and port infiltration and control of the money laundering networks Mexican cartels use to repatriate cash from fentanyl sales on American streets.

And this didn’t start with deadly synthetic opioids, either.

“Where the drugs come from dictates control. If marijuana is coming from Canada, then control lies there,” the source explained. “Some of the biggest black market marijuana organizations were Chinese organized crime groups based in Brooklyn and Flushing, Queens, supplied from Canada.

“You had organizations getting seven or eight tons of marijuana a week from Canada, all controlled by Chinese groups,” the source said. “And we have seen black market marijuana money flowing back into Canadian banks alongside fentanyl money.”

Canada’s legal framework currently contributes to its appeal for China-based criminal organizations. “Canada’s lenient laws make it an attractive market,” the expert explained. “If someone gets caught with a couple of kilos of fentanyl in Canada, the likelihood of facing a 25-year sentence is very low.”

The presence in Toronto and Vancouver of figures like Tse Chi Lop—a globally significant triad leader operating in Markham, Ontario, and with suspected links to Chinese Communist Party security networks—underscores the systemic gaps.

“Tse is a major player exploiting systemic gaps in Canadian intelligence and law enforcement collaboration,” the source asserted.

Tse Chi Lop was operating from Markham and locations across Asia prior to his arrest in the Netherlands and subsequent extradition to Australia. He is accused of being at the helm of a vast drug syndicate known as “The Company” or “Sam Gor,” which is alleged to have laundered billions of dollars through casinos, property investments, and front companies across the globe.

Reporting by The Bureau has found that British Columbia, and specifically Vancouver’s port, are critical transshipment and production hubs for Triad fentanyl producers and money launderers working in alignment with Mexican cartels and Iranian-state-linked criminals. Documents that surfaced in Ottawa’s Hogue Commission—mandated to investigate China’s interference in Canada’s recent federal elections—demonstrate that BC Premier David Eby flagged his government’s growing awareness of the national security threats related to fentanyl with Justin Trudeau’s former national security advisor.

A confidential federal document, released through access to information, states, according to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS): “Synthetic drugs are increasingly being produced in Canada using precursor chemicals largely sourced from China.”

“Preliminary reporting by the BC Coroner’s Service confirms that toxic, unregulated drugs claimed the lives of at least 2,511 people in British Columbia in 2023, the largest number of drug-related deaths ever reported to the agency,” the record says. “CSIS identifies more than 350 organized crime groups actively involved in the domestic illegal fentanyl market … which Premier Eby is particularly concerned about.”

A sanitized summary on Eby’s concerns from the Hogue Commission adds: “On fentanyl specifically, Canada, the United States, and Mexico are working on supply reduction, including as it relates to precursor chemicals and the prevention of commercial shipping exploitation. BC would be a critical partner in any supply reduction measures given that the Port of Vancouver is Canada’s largest port.”

But before Beijing’s chemical narcotics kingpins took over fentanyl money laundering networks from Canada, the story begins in the early 1990s when fentanyl first appeared on American streets, according to a source with full access to DEA investigative files.

The initial appearance of fentanyl in the United States was linked to a chemist in Ohio during 1992 or 1993, they said. This illicit operation led to hundreds of overdose deaths in cities like Chicago and New York, as heroin laced with fentanyl—known as “Tango & Cash”—flooded the streets. The DEA identified and dismantled the source, temporarily removing fentanyl from the illicit market.

Fentanyl seemed to vanish from the illicit market, lying dormant.

The mid-2000s saw a resurgence, this time with Mexican cartels entering the methamphetamine and fentanyl distribution game, and individuals of Chinese origin taking up roles in Mexico City. “One major case was Zhenli Ye Gon in 2007, where Mexican authorities seized $207 million from his home in Mexico City,” The Bureau’s source said. “He was a businessman accused of being involved in the trafficking of precursor chemicals for methamphetamine production.”

Ye Gon, born in Shanghai and running a pharma-company in Mexico, was believed to be perhaps the largest methamphetamine trafficker in the Western Hemisphere. Educated at an elite university in China, he made headlines not only for his alleged narcotics activities but also for his lavish lifestyle. While denying drug charges in the U.S., he claimed he had received duffel bags filled with cash from members of President Felipe Calderón’s party—a claim that was denied by officials. His arrest also caused a stir in Las Vegas, where Ye Gon was a “VIP” high roller who reportedly gambled more than $125 million, with the Venetian casino gifting him a Rolls-Royce.

Despite high-profile crackdowns, the threat of fentanyl ebbed and flowed, never truly disappearing.

Meanwhile, in 2005 and 2006, over a thousand deaths on Chicago’s South Side were traced to a fentanyl lab in Toluca, Mexico, operated by the Sinaloa Cartel. After the DEA shut it down, fentanyl essentially went dormant again.

A new chapter unfolded in 2013 as precursor chemicals—mainly N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (NPP) and 4-anilinopiperidine (4-ANPP)—began arriving from China. This is when fentanyl overdoses started to rise exponentially in Vancouver, where triads linked to Beijing command money laundering in North America.

“These chemicals were entering Southern California, Texas, and Arizona, smuggled south into Mexico, processed into fentanyl, and then brought back into the U.S., often mixed with Mexican heroin,” the U.S. government source explained.

At the time, a kilo of pure fentanyl cost about $3,000. By 2014, it was called “China White” because heroin was being laced with fentanyl, making it far more potent. In February 2015, the DEA issued its first national alert on fentanyl and began analyzing the role of Chinese organized crime in the fentanyl trade and related money laundering.

The profitability and efficiency of fentanyl compared to traditional narcotics like heroin made it an attractive commodity for drug cartels.

By 2016, fentanyl was being pressed into counterfeit pills, disguised as OxyContin, Percocet, or other legitimate pharmaceuticals. Dark web marketplaces and social media platforms became conduits for its distribution.

The merging of hardcore heroin users and “pill shoppers”—individuals seeking diverted pharmaceuticals—into a single user population occurred due to the prevalence of fentanyl-laced pills. This convergence signified a dangerous shift in the opioid crisis, broadening the scope of those at risk of overdose.

The profitability for traffickers was staggering. One pill could sell for $30 in New England, and Mexican cartels could make 250,000 pills from one kilo of fentanyl, which cost around $3,000 to $5,000. This was far more lucrative and efficient than heroin, which takes months to cultivate and process.

This shift marked a significant turning point in the global drug trade, with synthetic opioids overtaking traditional narcotics.

By 2016, entities linked to the Chinese state were entrenched in Mexico’s drug trade. Chinese companies were setting up operations in cartel-heavy cities, including mining companies, import-export businesses, and restaurants.

“The growth of Chinese influence in Mexico’s drug trade was undeniable,” the source asserted.

Recognizing the escalating crisis, the DEA launched Project Sleeping Giant in 2018. The initiative highlighted the role of Chinese organized crime, particularly the triads, in supplying precursor chemicals, laundering money for cartels, and trafficking black market marijuana.

“Most people don’t realize that Chinese organized crime has been upstream in the drug trade for decades,” the U.S. expert noted.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, drug trafficking organizations adapted swiftly. With borders closed and travel restricted, cartels started using express mail services like FedEx to ship fentanyl and methamphetamine.

This shift highlighted the cartels’ agility in exploiting vulnerabilities and adapting to global disruptions.

By 2022, the DEA intensified efforts to combat the fentanyl epidemic, initiating Operation Chem Kong to target Chinese chemical suppliers.

An often-overlooked aspect of the drug trade is the sophisticated money laundering operations that sustain it, fully integrated into China’s economy through triad money brokers. Chinese groups are now the largest money launderers in the U.S., outpacing even Colombian groups.

“We found Chinese networks picking up drug money in over 22 states,” the source explained. “They’d fly one-way to places like Georgia or Illinois, pick up cash, and drive it back to New York or the West Coast.”

Remarkably, these groups charged significantly lower fees than their Colombian counterparts, sometimes laundering money for free in exchange for access to U.S. dollars.

This strategy not only facilitated money laundering but also circumvented China’s strict currency controls, providing a dual benefit to the criminal organizations.

They used these drug-cash dollars to buy American goods, ship them to China, and resell them at massive markups. Chinese brokers weren’t just laundering fentanyl or meth money; they also laundered marijuana money and worked directly with triads. Operations like “Flush with Cash” in New York identified service providers moving over $1 billion annually to China.

But navigating the labyrinth of Chinese criminal organizations—and their connectivity with China’s economy and state actors—poses significant challenges for law enforcement.

“The challenge is the extreme compartmentalization in Chinese criminal groups,” the U.S. expert emphasized. “You might gain access to one part of the organization, but two levels up, everything is sealed off.”

High-level brokers operate multiple illicit enterprises simultaneously, making infiltration and dismantling exceedingly difficult.

The intricate tapestry of Chinese fentanyl trafficking highlights a convergence of international criminal enterprises exploiting systemic vulnerabilities across borders. The adaptability of these networks—in shifting trafficking methods, leveraging legal disparities, and innovating money laundering techniques—poses a formidable challenge to Western governments.

The leniency in certain jurisdictions including Canada not only hinders enforcement efforts but also incentivizes criminal activities by reducing risks and operational costs.

As the United States prepares to intensify its crackdown on fentanyl networks, having not only politicians and bureaucrats—but also the citizens they are serving—understand the importance of a multifaceted and multinational counter strategy is critical, because voters will drive the political will needed.

And this report, sourced from U.S. experts, provides a blueprint for other public interest journalists to follow.

“This briefing will help you paint the picture regarding Chinese organized crime, the triads, CCP, or PRC involvement with the drug trade and money laundering—particularly with precursor chemicals and black market marijuana,” the primary source explained.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

2025 Federal Election

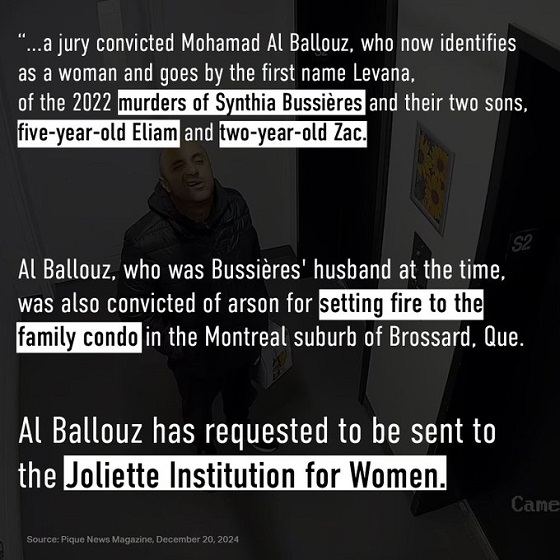

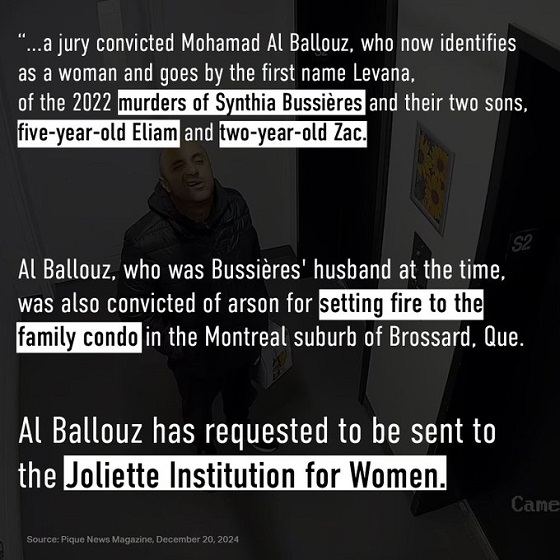

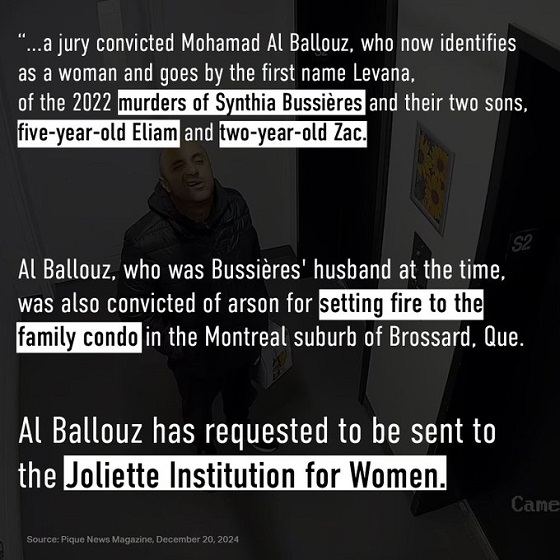

‘Sadistic’ Canadian murderer claiming to be woman denied transfer to female prison

From LifeSiteNews

The logical decision to house the male murderer with men flies in the face of the Liberal Party’s official stance, which is to incarcerate prisoners according to their ‘self-identified’ gender.

A Canadian man who butchered his family and now claims to be a woman will not be allowed to transfer to a female prison.

On April 8, Correctional Services Canada (CSC) announced that Mohamad Al Ballouz, who brutally murdered his wife and two children, will be sent to a men’s prison, despite claiming to be a woman, according to CTV News.

“When there are overriding health and safety concerns, the request is denied and alternatives are put in place to meet the offender’s gender‑related needs at the institution where they are incarcerated,” the CSC statement reads.

Following an assessment of Al Ballouz request, CSC confirmed that he “will be incarcerated in a men’s institution.”

On December 16, Al Ballouz, a 38-year-old from Quebec, was found guilty second-degree murder of his wife Synthia Bussières, first-degree murder of five-year-old Eliam and two-year-old Zac, and one count of attempted arson.

Crown prosecutor Éric Nadeau revealed that the murder took place in September 2022 when Al Ballouz slaughtered his family at their Brossard apartment. He stabbed his wife 23 times before suffocated his children and trying to set the apartment on fire. He then ingested windshield washer fluid, which is believed to have been a suicide attempt.

During the trial, Quebec Superior Justice Eric Downs described Al Ballouz, as having a “sadistic character” and being “deeply narcissistic.” He was sentenced to life imprisonment with no chance of parole for 25 years.

Throughout the trial, Al Ballouz, a biological male, claimed to be a woman and demanded that he be referred to as “Levana,” a change which was made after he was charged for his crimes. Notably, the Canadian Broadcasting Report’s (CBC’s) report of the case refers to the convicted murder as “she” and uses his fake name.

Following his sentencing, the murderer requested to be sent to the Joliette Institution for Women; however, Downs responded that is a decision for Correctional Service Canada.

Currently under the Liberal Party, the policy is to place prisoners according to their “self-identified” gender, not according to biology. As a result, male rapists and murderers can be sent to prison with females.

However, Al Ballouz’s case caused an uproar on social media as many pointed out that putting the murderer in a women’s prison would pose a danger to female inmates.

Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre has condemned the Liberal policy and promised that he would end this practice if elected.

“Surreal: A man who killed his wife and two kids now claims he is a woman to go to a female prison,” he wrote in a December 22 post on X.

“I can’t believe I have to say this: but when I’m PM, there will be no male prisoners in female jails,” Poilievre continued. “Period.”

Business

Canadian Police Raid Sophisticated Vancouver Fentanyl Labs, But Insist Millions of Pills Not Destined for U.S.

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

Mounties say labs outfitted with high-grade chemistry equipment and a trained chemist reveal transnational crime groups are advancing in technical sophistication and drug production capacity

Amid a growing trade war between Washington and Beijing, Canada—targeted alongside Mexico and China for special tariffs related to Chinese fentanyl supply chains—has dismantled a sophisticated network of fentanyl labs across British Columbia and arrested an academic lab chemist, the RCMP said Thursday.

At a press conference in Vancouver, senior investigators stood behind seized lab equipment and fentanyl supplies, telling reporters the operation had prevented millions of potentially lethal pills from reaching the streets.

“This interdiction has prevented several million potentially lethal doses of fentanyl from being produced and distributed across Canada,” said Cpl. Arash Seyed. But the presence of commercial-grade laboratory equipment at each of the sites—paired with the arrest of a suspect believed to have formal training in chemistry—signals an evolution in the capabilities of organized crime networks, with “progressively enhanced scientific and technical expertise among transnational organized crime groups involved in the production and distribution of illicit drugs,” Seyed added.

This investigation is ongoing, while the seized drugs, precursor chemicals, and other evidence continue to be processed, police said.

Recent Canadian data confirms the country has become an exporter of fentanyl, and experts identify British Columbia as the epicenter of clandestine labs supplied by Chinese precursors and linked to Mexican cartel distributors upstream.

In a statement that appears politically responsive to the evolving Trump trade threats, Assistant Commissioner David Teboul said, “There continues to be no evidence, in this case and others, that these labs are producing fentanyl for exportation into the United States.”

In late March, during coordinated raids across the suburban municipalities of Pitt Meadows, Mission, Aldergrove, Langley, and Richmond, investigators took down three clandestine fentanyl production sites.

The labs were described by the RCMP as “equipped with specialized chemical processing equipment often found in academic and professional research facilities.” Photos released by authorities show stainless steel reaction vessels, industrial filters, and what appear to be commercial-scale tablet presses and drying trays—pointing to mass production capabilities.

The takedown comes as Canada finds itself in the crosshairs of intensifying geopolitical tension.

Fentanyl remains the leading cause of drug-related deaths in Canada, with toxic supply chains increasingly linked to hybrid transnational networks involving Chinese chemical brokers and domestic Canadian producers.

RCMP said the sprawling B.C. lab probe was launched in the summer of 2023, with teams initiating an investigation into the importation of unregulated chemicals and commercial laboratory equipment that could be used for synthesizing illicit drugs including fentanyl, MDMA, and GHB.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoResearchers Link China’s Intelligence and Elite Influence Arms to B.C. Government, Liberal Party, and Trudeau-Appointed Senator

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanadian Police Raid Sophisticated Vancouver Fentanyl Labs, But Insist Millions of Pills Not Destined for U.S.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPoilievre Announces Plan To Cut Taxes By $100,000 Per Home

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoTwo Canadian police unions endorse Pierre Poilievre for PM

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoTaxpayers urge federal party leaders to drop home sale reporting to CRA

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCarney needs to cancel gun ban and buyback

-

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago‘Sadistic’ Canadian murderer claiming to be woman denied transfer to female prison

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

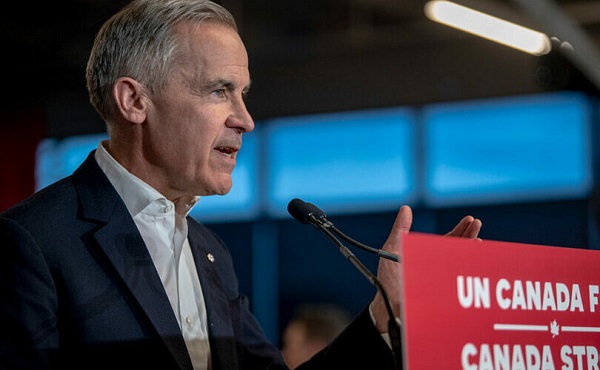

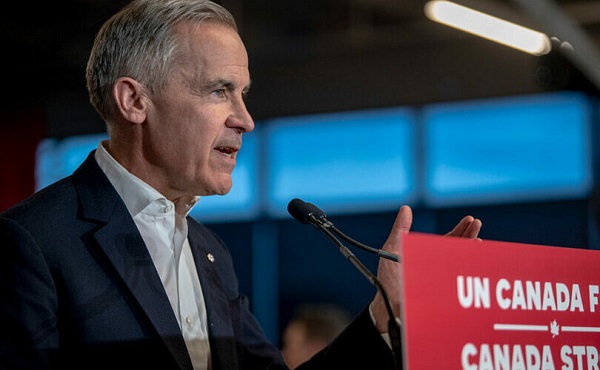

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMark Carney vows to provide sterilizing puberty blockers to children ‘without exception’