Fraser Institute

Powerful players count on corruption of ideal carbon tax

From the Fraser Institute

Prime Minister Trudeau recently whipped out the big guns of rhetoric and said the premiers of Alberta, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan are “misleading” Canadians and “not telling the truth” about the carbon tax. Also recently, a group of economists circulated a one-sided open letter extolling the virtues of carbon pricing.

Not to be left out, a few of us at the Fraser Institute recently debated whether the carbon tax should or could be reformed. Ross McKitrick and Elmira Aliakbari argued that while the existing carbon tax regime is badly marred by numerous greenhouse gas (GHG) regulations and mandates, is incompletely revenue-neutral, lacks uniformity across the economy and society, is set at an arbitrary price and so on, it remains repairable. “Of all the options,” they write, “it is widely acknowledged that a carbon tax allows the most flexibility and cost-effectiveness in the pursuit of society’s climate goals. The federal government has an opportunity to fix the shortcomings of its carbon tax plan and mitigate some of its associated economic costs.”

I argued, by contrast, that due to various incentives, Canada’s relevant decision-makers (politicians, regulators and big business) would all resist any reforms to the carbon tax that might bring it into the “ideal form” taught in schools of economics. To these groups, corruption of the “ideal carbon tax” is not a bug, it’s a feature.

Thus, governments face the constant allure of diverting tax revenues to favour one constituency over another. In the case of the carbon tax, Quebec is the big winner here. Atlantic Canada was also recently won by having its home heating oil exempted from carbon pricing (while out in the frosty plains, those using natural gas heating will feel the tax’s pinch).

Regulators, well, they live or die by the maintenance and growth of regulation. And when it comes to climate change, as McKitrick recently observed in a separate commentary, we’re not talking about only a few regulations. Canada has “clean fuel regulations, the oil-and-gas-sector emissions cap, the electricity sector coal phase-out, strict energy efficiency rules for new and existing buildings, new performance mandates for natural gas-fired generation plants, the regulatory blockade against liquified natural gas export facilities” and many more. All of these, he noted, are “boulders” blocking the implementation of an ideal carbon tax.

Finally, big business (such as Stellantis-LG, Volkswagen, Ford, Northvolt and others), which have been the recipients of subsidies for GHG-reducing activities, don’t want to see the driver of those subsidies (GHG regulations) repealed. And that’s only in the electric vehicle space. Governments also heavily subsidize wind and solar power businesses who get a 30 per cent investment tax credit though 2034. They also don’t want to see the underlying regulatory structures that justify the tax credit go away.

Clearly, all governments that tax GHG emissions divert some or all of the revenues raised into their general budgets, and none have removed regulations (or even reduced the rate of regulation) after implementing carbon-pricing. Yet many economists cling to the idea that carbon taxes are either fine as they are or can be reformed with modest tweaks. This is the great carbon-pricing will o’ the wisp, leading Canadian climate policy into a perilous swamp.

Author:

Business

Residents in economically free states reap the rewards

From the Fraser Institute

A report published by the Fraser Institute reaffirms just how much more economically free some states are compared with others. These are places where citizens are allowed to make more of their economic choices. Their taxes are lighter, and their regulatory burdens are easier. The benefits for workers, consumers and businesses have been clear for a long time.

There’s another group of states to watch: “movers” that have become much freer in recent decades. These are states that may not be the freest, but they have been cutting taxes and red tape enough to make a big difference.

How do they fare?

I recently explored this question using 22 years of data from the same Economic Freedom of North America index. The index uses 10 variables encompassing government spending, taxation and labour regulation to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states.

Some states, such as New Hampshire, have long topped the list. It’s been in the top five for three decades. With little room to grow, the Granite State’s level of economic freedom hasn’t budged much lately. Others, such as Alaska, have significantly improved economic freedom over the last two decades. Because it started so low, it remains relatively unfree at 43rd out of 50.

Three states—North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho—have managed to markedly increase and rank highly on economic freedom.

In 2000, North Carolina was the 19th most economically free state in the union. Though its labour market was relatively unhindered by the state’s government, its top marginal income tax rate was America’s ninth-highest, and it spent more money than most states.

From 2013 to 2022, North Carolina reduced its top marginal income tax rate from 7.75 per cent to 4.99 per cent, reduced government employment and allowed the minimum wage to fall relative to per-capita income. By 2022, it had the second-freest labour market in the country and was ninth in overall economic freedom.

North Dakota took a similar path, reducing its 5.54 per cent top income tax rate to 2.9 per cent, scaling back government employment, and lowering its minimum wage to better reflect local incomes. It went from the 27th most economically free state in the union in 2000 to the 10th freest by 2022.

Idaho saw the most significant improvement. The Gem State has steadily improved spending, taxing and labour market freedom, allowing it to rise from the 28th most economically free state in 2000 to the eighth freest in 2022.

We can contrast these three states with a group that has achieved equal and opposite distinction: California, Delaware, New Jersey and Maryland have managed to decrease economic freedom and end up among the least free overall.

What was the result?

The economies of the three liberating states have enjoyed almost twice as much economic growth. Controlling for inflation, North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho grew an average of 41 per cent since 2010. The four repressors grew by just 24 per cent.

Among liberators, statewide personal income grew 47 per cent from 2010 to 2022. Among repressors, it grew just 26 per cent.

In fact, when it comes to income growth per person, increases in economic freedom seem to matter even more than a state’s overall, long-term level of freedom. Meanwhile, when it comes to population growth, placing highly over longer periods of time matters more.

The liberators are not unique. There’s now a large body of international evidence documenting the freedom-prosperity connection. At the state level, high and growing levels of economic freedom go hand-in-hand with higher levels of income, entrepreneurship, in-migration and income mobility. In economically free states, incomes tend to grow faster at the top and bottom of the income ladder.

These states suffer less poverty, homelessness and food insecurity and may even have marginally happier, more philanthropic and more tolerant populations.

In short, liberation works. Repression doesn’t.

Alberta

Alberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Last Friday, less than a week before Christmas, the Smith government quietly released the final report from its Alberta Next Panel, which assessed Alberta’s role in Canada. Among other things, the panel recommends that the federal government transfer some of its tax revenue to provincial governments so they can assume more control over the delivery of provincial services. Based on Canada’s experience in the 1990s, this plan could deliver real benefits for Albertans and all Canadians.

Federations such as Canada typically work best when governments stick to their constitutional lanes. Indeed, one of the benefits of being a federalist country is that different levels of government assume responsibility for programs they’re best suited to deliver. For example, it’s logical that the federal government handle national defence, while provincial governments are typically best positioned to understand and address the unique health-care and education needs of their citizens.

But there’s currently a mismatch between the share of taxes the provinces collect and the cost of delivering provincial responsibilities (e.g. health care, education, childcare, and social services). As such, Ottawa uses transfers—including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT)—to financially support the provinces in their areas of responsibility. But these funds come with conditions.

Consider health care. To receive CHT payments from Ottawa, provinces must abide by the Canada Health Act, which effectively prevents the provinces from experimenting with new ways of delivering and financing health care—including policies that are successful in other universal health-care countries. Given Canada’s health-care system is one of the developed world’s most expensive universal systems, yet Canadians face some of the longest wait times for physicians and worst access to medical technology (e.g. MRIs) and hospital beds, these restrictions limit badly needed innovation and hurt patients.

To give the provinces more flexibility, the Alberta Next Panel suggests the federal government shift tax points (and transfer GST) to the provinces to better align provincial revenues with provincial responsibilities while eliminating “strings” attached to such federal transfers. In other words, Ottawa would transfer a portion of its tax revenues from the federal income tax and federal sales tax to the provincial government so they have funds to experiment with what works best for their citizens, without conditions on how that money can be used.

According to the Alberta Next Panel poll, at least in Alberta, a majority of citizens support this type of provincial autonomy in delivering provincial programs—and again, it’s paid off before.

In the 1990s, amid a fiscal crisis (greater in scale, but not dissimilar to the one Ottawa faces today), the federal government reduced welfare and social assistance transfers to the provinces while simultaneously removing most of the “strings” attached to these dollars. These reforms allowed the provinces to introduce work incentives, for example, which would have previously triggered a reduction in federal transfers. The change to federal transfers sparked a wave of reforms as the provinces experimented with new ways to improve their welfare programs, and ultimately led to significant innovation that reduced welfare dependency from a high of 3.1 million in 1994 to a low of 1.6 million in 2008, while also reducing government spending on social assistance.

The Smith government’s Alberta Next Panel wants the federal government to transfer some of its tax revenues to the provinces and reduce restrictions on provincial program delivery. As Canada’s experience in the 1990s shows, this could spur real innovation that ultimately improves services for Albertans and all Canadians.

-

Business2 days ago

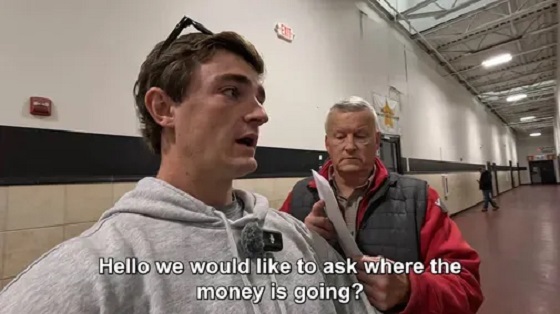

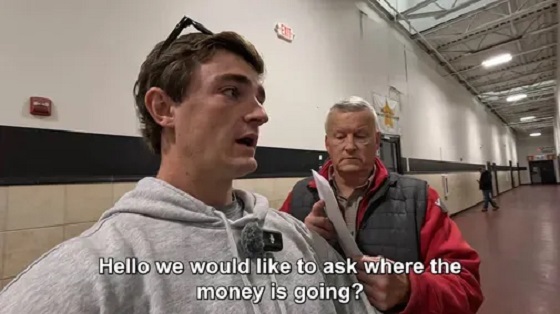

Business2 days agoLargest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days ago“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Business6 hours ago

Business6 hours agoLand use will be British Columbia’s biggest issue in 2026

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoUS Under Secretary of State Slams UK and EU Over Online Speech Regulation, Announces Release of Files on Past Censorship Efforts

-

Haultain Research18 hours ago

Haultain Research18 hours agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Energy6 hours ago

Energy6 hours agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG

-

Business3 hours ago

Business3 hours agoMainstream media missing in action as YouTuber blows lid off massive taxpayer fraud