Economy

Newly discovered business case for Canadian energy could unleash economic boom

From Resource Works

Canada has a hefty slate in recent years of big natural-resource projects that were abandoned, or put on a back burner, often because of government action or inaction.

One estimate is that Canada has seen $670 billion in cancelled resource projects since 2015, when Justin Trudeau became prime minister.

True, the Trudeau government in 2018 backed and took over the Trans Mountain oil pipeline expansion project, known as TMX. That’s been a success since May 2024, moving oil to U.S. and Asian buyers. It’s looking now to move more oil to Asia. And Ottawa is talking of First Nations getting some equity interest in it.

Many other major projects have been shelved or scrapped, though, some due to corporate economic decisions, but many due to governments.

One prime example was the Énergie Saguenay LNG project in Quebec. That $20-billion plan was fatally throttled in 2022 — on green grounds — by Quebec’s government and Trudeau’s minister of environment and climate change, Steven Guilbeault.

Now, with Trudeau leaving and a potential change federal government possible, there’s some early talk of reviving some projects. For example, Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston has urged Ottawa to “immediately” revive the Energy East oil pipeline project.

And U.S. President Donald Trump’s threats of tariffs on imports from Canada have underlined calls for new energy exports to new overseas customers.

We list below 31 projects that have been abandoned or shelved, or have not been heard from for years. They are listed in order of the year of cancellation, or the year they were last heard from.

Keltic LNG

This project was actually an LNG import facility that would then manufacture plastic pellets. It won its first government approval (from Nova Scotia) in 2007. But it never went ahead, and all approvals long ago expired.

Corridor Resources shale gas

Proposed in 2011, the idea was to produce from the huge shale-gas reserves in New Brunswick. But Corridor Resources (now called Headwater Exploration Inc) was unable to find a partner. And in 2014 the N.B. government put a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for gas; it is still in effect.

Dunkirk oil sands

Proposed by the billionaire Koch brothers of the U.S. in 2014, but ditched later that year, this Alberta project was supposed to produce up to 60,000 barrels a day, using the in-situ steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) process.

Kitsault LNG

Kitsault Energy proposed in 2013 an LNG-for-export project at the northern mining ghost town of Kitsault BC. It hoped to line up a pipeline partner, create an ‘energy corridor’, and to begin production in 2018. It said it was still working on cost estimates in 2014, and nothing was heard thereafter.

Carmon Creek oil sands

Shell proposed this in 2013, to produce 80,000 barrels a day. The company in 2014 said it would slow down the project while attempting to lower costs and improve its design. But in 2015, Shell gave up on it, giving a lack of pipelines to coastal waters as one reason.

Stewart LNG

The Canada Stewart Energy Group proposed in 2014 an LNG terminal near Stewart in northern BC. It aimed to produce 30 million tonnes a year, starting in 2017. It has not been heard from since 2014.

Watson Island LNG

This LNG terminal was proposed in 2014 by Watson Island LNG Corporation, to be located at Prince Rupert, with capacity to produce one million tonnes of LNG a year. There have been no updates since 2014, and the project’s website is no longer online.

Discovery LNG

Rockyview Resources was the developer of this LNG project at Campbell River on Vancouver Island, first proposed in 2014. It was a big plan, for 20 million tonnes of LNG a year, and would need a 300-km pipeline from the mainland. As of January 2018, Rockyview was reported still seeking partners, but there have been no updates since 2015.

Orca LNG

A Texas-based company got from Canada’s National Energy Board in 2015 a license to export 24 million tonnes of LNG a year, from a proposed plant at or near Prince Rupert. There has been no news from the developer since then.

New Times Energy LNG

New Times Energy proposed in 2015 to locate at Prince Rupert an LNG terminal capable of producing 12 million tonnes of LNG a year. Ottawa approved its export licence in 2016, but there has been no news of the project, or of any pipeline to feed it, since then.

Northern Gateway

Journalist Tom Fletcher recently looked in Northern Beat at the idea of reviving the $7.9-billion Northern Gateway pipeline, first proposed in 2008 and shelved in 2016.

“One new project that could be reactivated is the Northern Gateway oil pipeline, snuffed out by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s environmental posturing.

“Already burdened by court challenges, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway was killed by Trudeau’s 2016 declaration that oil tankers shouldn’t be allowed near the ‘Great Bear Rainforest.’

“He is among many urban people who are unaware this faux-Indigenous name was dreamed up by professional environmentalists at a fancy restaurant in San Francisco, explicitly to create a barrier for Canadian oil exports to Asia. . . ..

“Those Asia exports have finally begun to flow in significant volumes through the recent Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which has been mostly at capacity since it opened.”

Fletcher notes that in 2021 then-Conservative leader Erin O’Toole campaigned on a promise to revive the Northern Gateway pipeline.

“Whether a new federal government can or wants to revive Northern Gateway is unknown. But combined with Coastal Gaslink, it would build on a northern resource corridor that could also include the already-permitted Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line now proposed by TC Energy and the Nisga’a government.

“The Prince Rupert line would supply a floating LNG plant (the Nisga’a Nation’s Ksi Lisims LNG project) and new power lines along the energy corridor could help serve the needs of the broad expanse of northern B.C. that remains off the grid.”

Muskwa oil sands

Another project of the Koch brothers in Alberta’s oil sands, proposed in 2012, this project was to produce 10,000 barrels per day. It was scrapped in 2016, with the developer citing “regulatory uncertainty.”

Douglas Channel LNG

This modest (0.55 million tonnes a year) floating LNG project was led by Alta Gas. The plan was for a $400-million floating terminal in Douglas Channel near Kitimat. It was shelved in 2016, with Alta Gas citing a global surplus in LNG, and low prices.

Triton LNG

At the same time as scrapping Douglas Channel LNG (above), Alta Gas and partner Idemitsu Kosan of Japan put a freeze on the Triton LNG project in the same area. It was proposed in 2013, and was to have produced up to 2.3 million tonnes of LNG per year.

Energy East

Another classic and costly example of shelving was the $15.7-billion Energy East pipeline. This was proposed in 2013, the aim being to switch 3,000 km of the TransCanada gas pipeline to carry oil, and add another 1,500 km of oil pipeline and facilities. All this so it could move oil from Alberta and Saskatchewan to Quebec and New Brunswick refineries, for domestic use and for exports.

The project was strenuously attacked by environmental groups (and a number of First Nations) and a poll showed nearly 60% of Quebecers opposed it. Quebec politicians called for more stringent environmental rules to apply to it, and the Quebec government decided on a court challenge, to ensure the Quebec portion of the project met that province’s environmental laws and regulations.

Trans Canada (now TC Energy) then shelved the project in October 2017, citing “existing and likely future delays resulting from the regulatory process, the associated cost implications and the increasingly challenging issues and obstacles.” The project had already cost Trans Canada $1 billion.

(The same day, Trans Canada also scrapped its Eastern Mainline project, to add new gas pipeline and compression facilities to the existing system in Southern Ontario.)

New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs soon sought to revive Energy East, and discussed it with Trudeau. He quoted Trudeau as saying he’d be willing to discuss the issue again if Higgs was able to get Quebec onside. But Trans Canada repeated its announced decision.

Now, with Trump threatening tariffs, Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston is calling on Ottawa to approve the Energy East oil pipeline. He said Trump’s tariffs mean here is “urgency” to strengthen the country through projects such as Energy East.

Earlier, commentator Brian Zinchuk of Pipeline Online urged: “If (Conservative leader Pierre) Poilievre wins a massive majority, can we PLEASE build the Energy East Pipeline?”

Zinchuk added: “So what could a newly empowered government with a massive majority do? Here’s a novel idea: Call up TC Energy and ask them to dust off their 2014 application to build the Energy East Pipeline. We’re going to need it.”

Mackenzie Valley Pipeline

This project was first proposed in the early 1970s to move natural gas from the Beaufort Sea to northern Alberta, and then to tie in to existing gas pipelines there.

Ottawa launched in 1974 a federal inquiry into the project. After three years (and at a cost of $5.3-million) inquiry commissioner Thomas Berger said in 1977 that the 1,220-km pipeline should be postponed for 10 years, estimating that it would take that long for land claims to be settled and for Indigenous Peoples to be ready for the impact of such a project.

Eventually, after another six years of review, the Mackenzie Valley pipeline was granted federal approval in 2011, subject to 264 conditions.

But by 2017 the initially estimated costs of $8 billion had risen to $16.2 billion, and the joint-venture partnership of Imperial Oil, ConocoPhillips Canada, ExxonMobil Canada and the Aboriginal Pipeline Group announced abandonment of the project, citing natural gas prices – but also the long regulatory process.

Said an Imperial Oil official: “Our initial estimate for the timing for the regulatory process was somewhere between 22 and 24 months. We filed for regulatory approval in October 2004 and we received final regulatory approval in 2011. I’ll leave it up to you to decide if that is a reasonable amount of time for a significant capital investment project.”

Prince Rupert LNG

Shell Canada took over in 2016 the BG Group’s back-burnered 2012 proposal for an $11-billion LNG terminal on Ridley Island, Prince Rupert. It was to produce 21 million tonnes of LNG per year. But in 2017, Shell shelved the project.

That also killed the $9.6-billion Westcoast Connector pipeline proposed by Enbridge in 2012. This was to build an 850-km natural gas pipeline corridor from northeast B.C. to Ridley Island to feed gas to Prince Rupert LNG.

There followed recently some thought that this Westcoast Connector pipeline could be revived, to feed the Nisga’a Nation’s proposed Ksi Lisims LNG project, but Ksi Lisims chose to take over the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline (PRGT).

Pacific Northwest LNG

Pacific NorthWest LNG proposed in 2013 a $36-billion LNG-for-export plant on Lelu Island south of Prince Rupert BC.

It was to produce up to 20.5 million tonnes of LNG a year, and would include a marine terminal for loading LNG on to vessels for export to markets in Asia.

As ever, the proposal ran into opposition from environmental and some (but not all) Indigenous groups. And in 2017, Malaysia’s Petronas and its minority partners (China’s Sinopec, Japan’s JAPEX, Indian Oil Corporation and PetroleumBrunei) decided not to proceed.

They cited “changes in market conditions.” But CEO Mike Rose of Tourmaline Oil, Canada’s largest natural-gas producer, pointed a finger at governments, saying “government dithering” played a role in the cancellation.

“They [Petronas] kept getting held up. . . . All levels of government were trying to squeeze more money out of them.”

Rose said a “more effective, streamlined approval process,” would have seen Petronas make a final investment decision on the project three years earlier, when LNG prices were much higher.

(Petronas continues to be a 25% partner in the LNG Canada project, which goes online later this year.)

The Pacific NorthWest LNG plant would have been fed by TC Energy’s 900-km Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline (PRGT). The permits for that line now are owned by the Nisg̱a’a First Nation and partner Western LNG. They propose a route change so the line can feed the Nation’s planned Ksi Lisims LNG plant. The B.C. Environmental Assessment Office now is considering whether the pipeline’s permits are still valid.

Aurora LNG

Nexen Energy, with Chinese and Japanese partners, proposed in 2014 the $28-billion Aurora LNG terminal on Digby Island, Prince Rupert. It would have produced up to 24 million tonnes of LNG a year. The partners ditched the plan in 2017, citing the economics.

WCC LNG

Exxon Mobil and Calgary-based Imperial Oil proposed in 2015 this $25-billion LNG export facility on Tuck Inlet, Prince Rupert. It was to produce some 30 million tonnes per year. The partners scrapped the project in 2018, without explanation.

Grassy Point LNG

Australia’s Woodside Energy proposed in 2014 a $10-billion facility 30 km north of Prince Rupert, to produce up to 20 million tonnes of LNG per year. Woodside shelved the plan in 2018. It said it would focus instead on the Kitimat LNG project with Chevron Canada (but that also died on the drawing board. (See ‘Kitimat LNG’ farther below)

Aspen oil sands

An Imperial Oil project, proposed in 2013, was to produce up to 150,000 barrels of bitumen a day. The $7-billion project was put on hold in 2019.

Kwispaa LNG

Proposed in 2014, this was an $18-billion project for an LNG plant near Bamfield on Vancouver Island, with an associated natural-gas pipeline. It was to be developed by Steelhead LNG Corporation through a co-management partnership with the Huu-ay-aht First Nations. The plan was to produce 12 million tonnes a year, and later up to 24 million. Steelhead stopped work on it in 2019, and in 2022 Ottawa formally terminated the environmental-assessment window for the project.

Frontier Oil Sands

Teck proposed this $20.6-billion mining project in Alberta’s oil sands in 2012, but gave up the idea in 2020. It would have had production capacity of about 260,000 barrels a day.

Kitimat LNG

Kitimat LNG was a $30-billion LNG-for-export plant at Kitimat BC, proposed in 2018 by Chevron Canada and Australia’s Woodside Energy. It was designed to produce up to 10 million tonnes of LNG a year.

Chevron sought to sell its share of the project but failed to find a buyer, and in the end Chevron and Woodside shelved the project in 2021.

Kitimat LNG would have been fed gas bv the proposed Pacific Trails Pipeline, a project by Chevron and Apache Corporation. Woodside Australia had bought Apache’s stake in the project for $2.75 billion in 2014. The pipeline plan has also been put away.

Goldboro LNG

Alberta energy company Pieridae proposed in 2011 an LNG plant on Nova Scotia’s east shore. The plan was to ship 10 million tonnes per year to Europe. But the project failed to win $925 million in federal funding, and Pieridae bailed out in 2021

Keystone XL

The $8-billion Keystone XL pipeline was proposed in 2008 by TC Energy, to deliver Alberta oil to Nebraska, and then, through existing pipelines, to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The project got its key U.S. presidential permit from then-president Donald Trump in 2017. Work eventually began in 2020, with the Alberta government kicking in $1.5 billion, and a promise of a $6-billion loan guarantee, in hopes of completion in 2023.

But under pressure from environmental groups, U.S. president Joe Biden revoked the permit on his first day in office on January 20, 2021, citing the “climate crisis.”

So this was, then, a rare Canadian project cancellation engineered by the U.S., not by Canada.

Énergie Saguenay

In 2015 came GNL Québec’s $20-billion proposal to build an LNG plant at the port of Saguenay in Quebec.

The Énergie Saguenay project, backed by Ruby Capital of the U.S., would connect to TC Energy’s Canadian Mainline, the big natural gas pipeline that carries gas from Western Canada to markets in Canada and the United States. The connection would be via a 780-km pipeline from northeastern Ontario to Saguenay, proposed by Gazoduq Inc.

Énergie Saguenay said its plant would produce 10.5 million tonnes of LNG a year. (The LNG Canada plant in B.C. will produce up to 14 million tonnes a year.) Énergie Saguenay said it would export its LNG via the St. Lawrence and Saguenay Rivers. It spoke of 140-165 shipments per year

The project raised considerable interest, as Germany, Latvia and Ukraine were expressing interest in importing Canadian LNG. Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz came to Canada in the summer of 2022 and asked Trudeau about LNG exports.

Trudeau, though, said he saw no business case for LNG exports to Europe, and said Canada could always send natural gas to the U.S., where Americans could turn it into American LNG and send that to Europe. (This was already happening, and continues.)

In the end, the Quebec government, which initially supported Énergie Saguenay, changed its mind and pulled the plug on environmental grounds.

Then Steven Guilbeault, federal minister of environment and climate change, hammered home the final coffin nail in 2022, saying: “The Énergie Saguenay Project underwent a rigorous review that clearly demonstrates that the negative effects the project would have on the environment are in no way justifiable.”

That regulatory rejection has led to a $20.12-billion international damage claim against the federal government by Ruby Capital.

Bear Head LNG

Bear Head Energy planned in 2014 to build an LNG-for-export plant on the Strait of Canso, Nova Scotia. It was to send 12 million tonnes a year to Europe. But in 2023 Bear Head, under new ownership, announced plans instead to produce hydrogen for export.

Port Edward LNG

Planning started in 2019 for this $450-million small-scale LNG project, for a site east of Port Edward BC. It was to ship LNG overseas in containers, but the project was scrapped in 2024.

Enbridge Line 5

Under appeal is a U.S. court order to shut down, by 2026, this pipeline that carries Canadian oil to Ontario, by way of Wisconsin and Michigan. In the court case, the Wisconsin-based Bad River Band, through whose territory the pipeline runs, seeks to have it shut down.

A U.S. district court ordered Enbridge in 2023 to shut down parts of the pipeline within three years and pay the band $5.2 million for trespassing on its land. Enbridge is appealing (and so is the Bad River Band, which wants an immediate shutdown.)

What’s next?

While there has been a little chatter about reviving some of the scratched projects, there have been no formal proposals for resurrections, and Canada’s current attention is on Donald Trump and his promised tariffs in imports from Canada

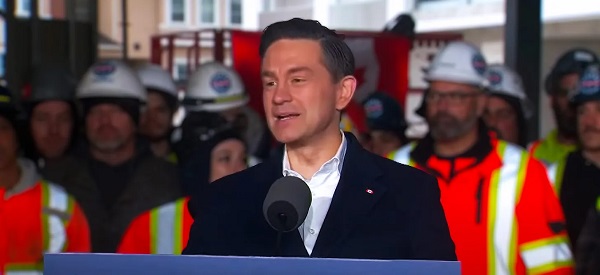

On the political front in Canada, national Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre said in a recent speech in Vancouver: “By blocking pipelines and LNG plants in Canada, the Liberals have forced Canadians to sell almost all of our energy to the United States, giving President Trump massive leverage in making these tariff threats.”.

He said that that if he was prime minister, he would have approved pipelines such as Northern Gateway and Energy East, as well as giving fast-track approvals for LNG plants, thus giving Canada more export options.

And Poilievre promised to allow pipeline companies on First Nations lands to pay some of their federal tax to affected nations.

“Then these communities will have a very powerful incentive to say yes, and they can use some of that money to defeat poverty, build schools and hospitals and clean water and other essentials for their people.”

But now Canada has first to cope with Trump’s Fortress America economic-warfare plans.

Business

Is Government Inflation Reporting Accurate?

David Clinton

David Clinton

Who ya gonna believe: official CPI figures or your lyin’ eyes?

Great news! We’ve brought inflation back under control and stuff is now only costing you 2.4 percent more than it did last year!

That’s more or less the message we’ve been hearing from governments over the past couple of years. And in fact, the official Statistics Canada consumer price index (CPI) numbers do show us that the “all-items” index in 2024 was only 2.4 percent higher than in 2023. Fantastic.

So why doesn’t it feel fantastic?

Well statistics are funny that way. When you’ve got lots of numbers, there are all kinds of ways to dress ‘em up before presenting them as an index (or chart). And there really is no one combination of adjustments and corrections that’s definitively “right”. So I’m sure Statistics Canada isn’t trying to misrepresent things.

But I’m also curious to test whether the CPI is truly representative of Canadians’ real financial experiences. My first attempt to create my own alternative “consumer price index”, involved Statistics Canada’s “Detailed household final consumption expenditure”. That table contains actual dollar figures for nation-wide spending on a wide range of consumer items. To represent the costs Canadian’s face when shopping for basics, I selected these nine categories:

- Food and non-alcoholic beverages

- Clothing and footwear

- Housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels

- Major household appliances

- Pharmaceutical products and other medical products (except cannabis)

- Transport

- Communications

- University education

- Property insurance

I then took the fourth quarter (Q4) numbers for each of those categories for all the years between 2013 and 2024 and divided them by the total population of the country for each year. That gave me an accurate picture of per capita spending on core cost-of-living items.

Overall, living and breathing through Q4 2013 would have cost the average Canadian $4,356.38 (or $17,425.52 for a full year). Spending for those same categories in Q4 2024, however, cost us $6,266.48 – a 43.85 percent increase.

By contrast, the official CPI over those years rose only 31.03 percent. That’s quite the difference. Here’s how the year-over-year changes in CPI inflation vs actual spending inflation compare:

As you can see, with the exception of 2020 (when COVID left us with nothing to buy), the official inflation number was consistently and significantly lower than actual spending. And, in the case of 2021, it was more than double.

Since 2023, the items with the largest price growth were university education (57.46 percent), major household appliances (52.67 percent), and housing, water, electricity, gas, and other fuels (50.79).

Having said all that, you could justifiably argue that the true cost of living hasn’t really gone up that much, but that at least part of the increase in spending is due to a growing taste for luxury items and high volume consumption. I can’t put a precise number on that influence, but I suspect it’s not trivial.

Since data on spending doesn’t seem to be the best measure of inflation, perhaps I could build my own basket of costs and compare those numbers to the official CPI. To do that, I collected average monthly costs for gasoline, home rentals, a selection of 14 core grocery items, and taxes paid by the average Canadian homeowner.¹ I calculated the tax burden (federal, provincial, property, and consumption) using the average of the estimates of two AI models.

How did the inflation represented by my custom basket compare with the official CPI? Well between 2017 and 2024, the Statistics Canada’s CPI grew by 23.39 percent. Over that same time, the monthly cost of my basket grew from $4,514.74 to $5,665.18; a difference of 25.48 percent. That’s not nearly as dramatic a difference as we saw when we measured spending, but it’s not negligible either.

The very fact that the government makes all this data freely available to us is evidence that they’re not out to hide the truth. But it can’t hurt to keep an active and independent eye on them, too.

Subscribe to The Audit.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

2025 Federal Election

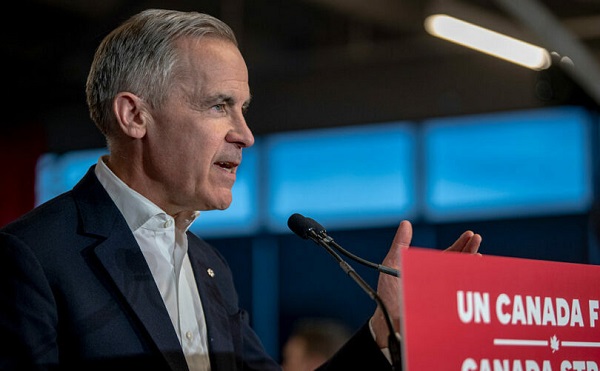

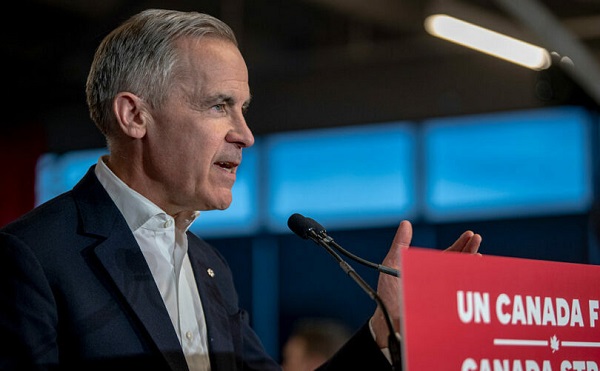

Carney’s Hidden Climate Finance Agenda

From Energy Now

By Tammy Nemeth and Ron Wallace

It is high time that Canadians discuss and understand Mark Carney’s avowed plan to re-align capital with global Net Zero goals.

Mark Carney’s economic vision for Canada, one that spans energy, housing and defence, rests on an unspoken, largely undisclosed, linchpin: Climate Finance – one that promises a Net Zero future for Canada but which masks a radical economic overhaul.

Regrettably, Carney’s potential approach to a Net Zero future remains largely unexamined in this election. As the former chair of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), Carney has proposed new policies, offices, agencies, and bureaus required to achieve these goals.. Pieced together from his presentations, discussions, testimonies and book, Carney’s approach to climate finance appears to have four pillars: mandatory climate disclosures, mandatory transition plans, centralized data sharing via the United Nations’ Net Zero Data Public Utility (NZDPU) and compliance with voluntary carbon markets (VCMs). There are serious issues for Canada’s economy if these principles were to form the core values for policies under a potential Liberal government.

About the first pillar Carney has been unequivocal: “Achieving net zero requires a whole economy transition.” This would require a restructuring energy and financial systems to shift away from fossil fuels to renewable energy with Carney insisting repeatedly in his book that “every financial [and business] decision takes climate change into account.” Climate finance, unlike broader sustainable finance with its Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) focus would channel capital into sectors aligned with a 2050 Net Zero trajectory. Carney states: “Companies, and those who invest in them…who are part of the solution, will be rewarded. Those lagging behind…will be punished.” In other words, capital would flow to compliant firms but be withheld from so-called “high emitters”.

How will investors, banks and insurers distinguish solution from problem? Mandatory climate disclosures, aligned with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), would compel firms to report emissions and outline their Net Zero strategies. Canada’s Sustainability Standards Board has adopted these methodologies, despite concerns they would disadvantage Canadian businesses. Here, Carney repeatedly emphasizes disclosures as the cornerstone to track emissions data required to shift capital away from “high emitters”. Without this, he claims, large institutional investors lack the data on supply chains to make informed decisions to shift capital to businesses that are Net Zero compliant.

The second pillar, Mandatory Transition Plans would require companies to map a 2050 Net Zero trajectory for emission reduction targets. Failure to meet those targets would invite pressure from investors, banks, or activists, who may pursue litigation for non-compliance. The UK’s Transition Plan Task Force, now part of ISSB, provides this standardized framework. Carney, while at GFANZ, advocated using transition plans for a “managed phase-out” of high-emitting assets like coal, oil and gas, not just through divestment but by financing emissions reductions. “As part of their transition planning, [GFANZ] members should establish and apply financing policies to phase out and align carbon-intensive sectors and activities, such as thermal coal, oil and gas and deforestation, not only through asset divestment but also through transition finance that reduces real world emissions. To assist with these efforts GFANZ will continue to develop and implement a framework for the Managed Phase-out of high-emitting assets.” Clearly, the purpose of this is to ensure companies either decarbonize or face capital withdrawal.

The third pillar is the United Nations’ Net Zero Data Public Utility (NZDPU), a centralized platform for emissions and transition data. Carney insists these data be freely accessible, enabling investors, banks and insurers to judge companies’ progress to Net Zero. As Carney noted in 2021: “Private finance is judging…banks, pension funds and asset managers have to show where they are in the transition to Net Zero.” Hence, compliant firms would receive investment; laggards would face divestment.

Finally, voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) allow companies to offset emissions by purchasing credits from projects like reforestation. Carney, who launched the Taskforce on Scaling VCMs in 2020, has insisted on monitoring, verification and lifecycle tracking. At a 2024 Beijing conference, he suggested major jurisdictions could establish VCMs by COP 30 (planned for 2025 in Brazil) to create a global market. If Canada mandates VCMs, businesses especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs) would face much higher compliance costs with credits available only to those that demonstrate progress with transition plans.

These potential mandatory disclosures and transition plans would burden Canadian businesses with material costs and legal risks that constitute an economic gamble which few may recognize but all should weigh. Do Canadians truly want a government that has an undisclosed climate finance agenda that would be subservient to an opaque globalized Net Zero agenda?

Tammy Nemeth is a U.K.-based strategic energy analyst. Ron Wallace is an executive fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and the Canada West Foundation.

-

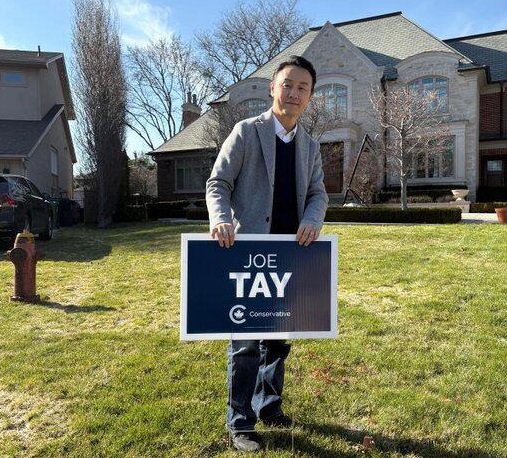

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMark Carney Wants You to Forget He Clearly Opposes the Development and Export of Canada’s Natural Resources

-

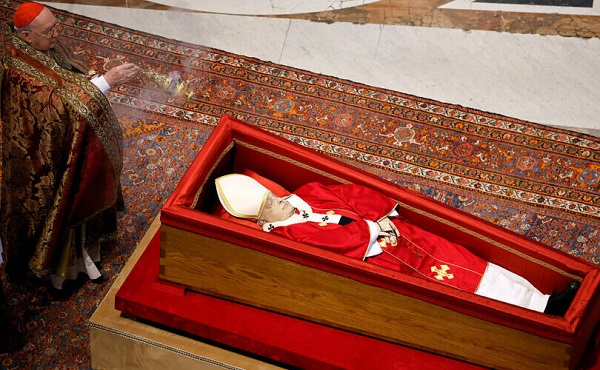

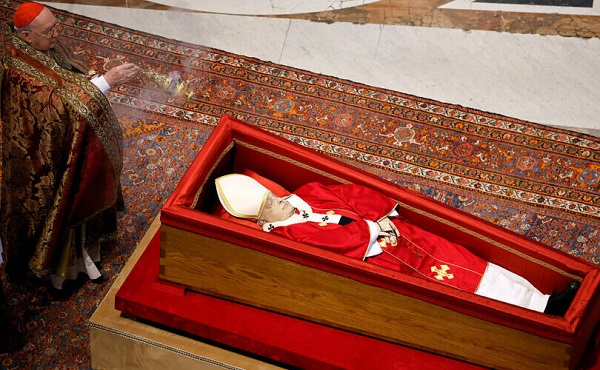

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPope Francis’ body on display at the Vatican until Friday

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHudson’s Bay Bid Raises Red Flags Over Foreign Influence

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCanada’s pipeline builders ready to get to work

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoFormer WEF insider accuses Mark Carney of using fear tactics to usher globalism into Canada

-

2025 Federal Election13 hours ago

2025 Federal Election13 hours agoCarney’s Hidden Climate Finance Agenda

-

COVID-191 day ago

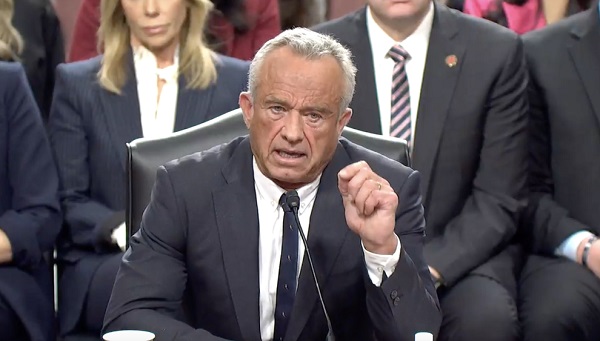

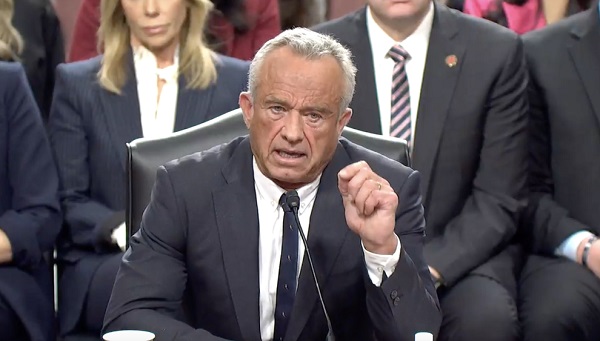

COVID-191 day agoRFK Jr. Launches Long-Awaited Offensive Against COVID-19 mRNA Shots

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCanada’s press tries to turn the gender debate into a non-issue, pretend it’s not happening