Fraser Institute

New Prime Minister Carney’s Fiscal Math Doesn’t Add Up

From the Fraser Institute

By Jason Clemens and Jake Fuss

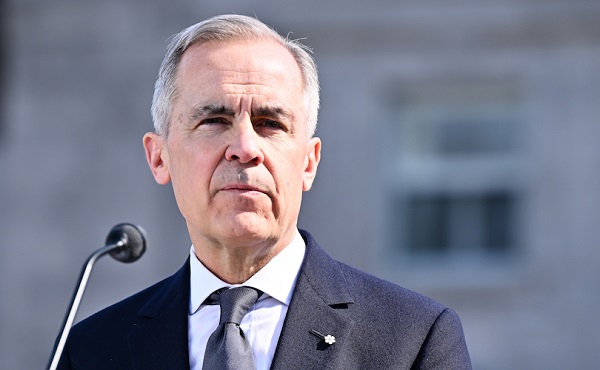

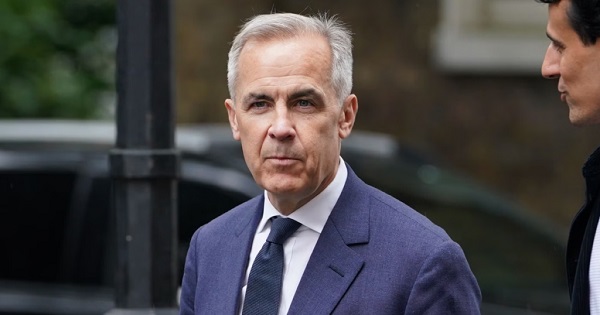

For the first time in Canada’s history, the Prime Minister has never sought or won a democratic election in any parliament. Mark Carney’s victory to replace Justin Trudeau as the leader of the Liberal Party means he is now the Prime Minister. Carney’s resume and achievements make him one of the most accomplished prime ministers ever. Still, there are a number of basic questions about Carney’s fiscal and economic math that Canadians need to consider carefully as we enter an election.

Carney’s accomplishments should be recognized. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from Harvard and both a masters and doctoral degrees in economics from Oxford University. He spent over a decade at Goldman Sachs, a leading US-based financial firm then left to take up senior positions at both the Bank of Canada and later the Department of Finance. He became the Governor of the Bank of Canada in 2007 and then the Governor of the Bank of England in 2012. After his tenure at the Bank of England, Carney took up a number of private sector posts including chairman at Brookfield Asset Management, a major Canadian company.

Despite these obvious accomplishments and a deep CV, Carney’s proposed fiscal policies pose a number of serious questions.

Carney self-characterizes as a pragmatist and someone who will bring the Liberal Party back to the political centre after having been pushed to the left by former prime minister Justin Trudeau. Even former prime minister Jean Chrétien, one of the country’s most electorally successful prime ministers called for the party to move back to the centre.

Specifically, Carney said he would “cap” the size of the federal government workforce and reduce federal spending through a review of program spending as was done in 1994-95. He also indicated that the operating budget would be balanced within three years. He criticized the current government for spending too much and not investing enough, and for missing spending targets and violating its own fiscal guardrails. The implication of all these policies is that the role of the federal government will be rolled back with reductions in spending and federal employment, and reducing regulations. In many ways, these policies mirror those of former prime minister Chrétien.

However, there are numerous statements by Carney that seem to contradict these policies, or at the very least, water them down significantly. Consider, for instance, that Carney has indicated there will be no cuts to transfers to provincial governments (19.8 per cent of budget spending), no reductions in the income-transfers to individuals and families (25.8 per cent), and the government doesn’t determine interest charges on its debt (another 9.7 per cent). So, Carney has already taken over half the federal budget off the table for reductions.

It’s not clear whether he would reduce what’s referred to as “Other Transfers” which includes support for EV programs and investment incentives. This represents 17.9 per cent of the current budget. And if you read any of Carney’s climate-related initiatives, it appears this category of spending will actually increase, not decrease. Moreover, Carney stated he won’t touch some transfers such as the national dental care and pharmacare programs.

The major remaining category of federal spending is “operating expenses”, which includes the costs of running more than 100 government departments, agencies and Crown corporations. It’s expected to reach $130.6 billion this year and represents 23.4 per cent of the federal budget. But again, Carney has only committed to “capping” the federal workforce despite significant growth since 2015 and then review programs. Unless he’s willing to actually reduce federal employment and/or challenge existing contracts with the civil service, it’s not clear how he can find meaningful savings in the short term.

Recall that the expected deficit this year is $42.2 billion and to balance the budget over the next three years, Carney needs to find roughly $30 billion in savings. (Some of the deficit reduction is expected to come from economic growth, which increases government revenues).

However, this ignores the pressure on the federal government to markedly and quickly increase defense spending. A recent analysis estimated that the federal government would have to increase defense spending in 2027-28 by $68.8 billion to meet its NATO commitment, which is what President Trump is demanding. This single measure of spending could materially derail the new prime minister’s commitment to a balanced budget within three years.

But Carney has complicated the nation’s finances by committing to separating operating spending from capital spending. The former are annual spending requirements like salaries and wages to federal employees, income transfers to people through programs like EI and Old Age Security, and transfers to the provinces for health and social programs. Carney has committed to balancing the revenues collected for these purposes against spending.

However, he wants to remove anything that is deemed an “investment” or “capital”. That means spending on infrastructure like roads and ports, defense spending on equipment, and energy projects.

While Carney has committed to only running a “small deficit” on such spending, the commitment is eerily similar to Trudeau’s commitment in 2015 to run “small deficits” for just “three years” and the budget will balance itself through economic growth. The total federal gross debt has increased from $1.1 trillion when Trudeau took office in 2015 to an estimated $2.3 trillion this year.

The clear risk is that a Carney government will simply reduce spending in the operating budget and move it to the capital budget, thus balancing the latter while still piling up government debt.

Clarity is required from the new prime minister with respect to: 1) What operating expenses does he plan to reduce (or perhaps more generally is open to reducing) over the next three years to reach a balanced operating budget? 2) What specific commitment is Carney making on defense spending over the next three years? 3) What current spending will the new prime minister move or potentially move from the budget to his new capital budget? And finally, 4) What measures will be taken if revenues don’t materialize as expected and/or spending increases more than planned to ensure a balanced operating budget in three years?

Until greater clarity and details are provided, it’s hard, even near impossible, to know the extent to which the new prime minister is pragmatically offering a plan for more sustainable government finances versus playing politics by promising everything to everyone.

Business

Trumpian chaos—where we are now and what’s coming for Canada

From the Fraser Institute

As we pause to catch our breath amid the ongoing drama of President Donald Trump’s whack-a-mole tariff war, there’s both good and bad news from a Canadian perspective.

On the positive side, Canada (together with Mexico) was not specifically targeted when the president outlined the details of his so-called “reciprocal” tariffs on April 2. These new levies—ranging from 10 per cent to more than 40 per cent, depending on the country—will affect most categories of exports from virtually every U.S. trading partner, but fortunately not America’s two co-signatories to the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). Instead, apart from a handful of significant economic sectors (discussed below), Canadian exporters, for the moment, will be able to sell tariff-free into the U.S. market, provided they are compliant with the rules and paperwork requirements stipulated in CUSMA. That’s a ray of sunshine in an otherwise dark sky.

On April 9, the president agreed to a 90-day pause on his sweeping reciprocal tariffs, perhaps because of plunging U.S. and global stock markets and mounting fears of economic calamity. At the same time, he announced a jaw-dropping 125 per cent tariff on imports from China, which then immediately retaliated with steep duties of its own on all U.S. goods entering the country.

The risk remains that when the dust settles, the U.S will end up applying much higher tariffs on imports from most of the world. Should President Trump adopt the reciprocal levies announced on April 2 and stick with the 125 per cent tariff on imports from China, Yale University researchers estimate that the average effective U.S. tariff rate will soar to 25.3 per cent—more than 10 times higher than the average over the preceding 25 years. That’s one measure of the disruption that Trump has visited upon the international trading system.

For Canada, the average U.S. tariff would be lower, between 4 and 5 per cent, reflecting the benefits of CUSMA, albeit somewhat offset by the negative impact of the 25 per cent levies the U.S. is imposing on all imports of steel, aluminum, and motor vehicles and parts, along with separate punitive duties on softwood lumber imported from Canada. American tariffs on these Canadian export sectors will undoubtedly exact a toll on our economy. But the damage would be considerably greater if Canada was subject to across-the-board U.S. reciprocal tariffs.

Where does all of this leave Canada’s $3.3 trillion economy as of the second quarter of 2025?

Late last year, most forecasters were expecting a modest pick-up in growth after a notably lacklustre 2024, mainly thanks to lower interest rates and reduced borrowing costs for households and businesses. However, that widely-shared view didn’t account for President Trump’s wholesale assault on the global economic system—“a new economic crisis,” as Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem described the situation in late March.

Back in February, the central bank took a stab at modelling the effects of matching U.S. and Canadian tariffs of 25 per cent, levied on all bilateral goods trade (apart from energy where a lower tariff rate was assumed). Its projections pointed to a permanent loss of Canadian economic output (real GDP) on the order of 2-3 per cent, a double-digit percentage decline in business investment, weaker consumption and a substantial fall in the value of Canadian exports over 2025/26. The Bank’s modelling also foresaw a lower Canadian dollar and a temporary jump in inflation, with the latter due primarily to Canada’s assumed retaliatory tariffs.

The macroeconomic scenario outlined in the Bank of Canada’s January study was dire enough, signalling a Canadian recession stretching over most of 2025 and well into 2026. But seen through today’s lens, the Bank’s earlier analysis looks too optimistic, as it failed to incorporate the worldwide dimensions of President Trump’s tariff barrage, including the scale of the retaliation planned by America’s aggrieved trading partners.

Even if it escapes the worst of Trump’s tariffs, Canada stands to suffer from a gruesome mix of slower global growth, a probable U.S. recession, and falling prices for oil, minerals and other natural resource products, which collectively comprise around half of the country’s international exports. Already there has been a marked erosion of Canadian business confidence, as reported in the Bank of Canada’s spring Business Outlook Survey, with one-third of firms now expecting a recession and hiring intentions sinking to the lowest level in a decade. Most respondents to the Bank’s survey also anticipate rising business input costs and higher Canadian inflation in 2025.

Worryingly, the latest Bank of Canada survey was completed in February; since then, the intensity of the Trumpian chaos has continued to increase. Among other things, the uncertainty that is an inevitable by-product of the president’s shambolic policymaking is having a decisively negative impact on business investment in many industries—in Canada, to be sure, but also in the United States. As two American business analysts recently observed: “With tariff policy shifting not day by day, but hour by hour… business investment is entirely paralyzed—and will continue to be frozen for the foreseeable future. That is exactly the opposite of what Trump intended.”

It doesn’t help that Canada is in the midst of a federal election, and that the government is therefore “otherwise occupied.” Once Canadian voters have spoken, the government elected on April 28 must deal with a deteriorating economy, navigate through the tariff fog and determine how to reset economic and security relations with our principal ally and commercial partner in the turbulent era of Trump 2.0.

2025 Federal Election

Does Canada Need a DOGE?

From the Fraser Institute

By Philip Cross

The legions of Canadians wanting to see government spending shrink probably look enviously at how Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is slashing some government programs in the United States, even if DOGE’s non-surgical chainsaw approach is controversial, to say the least.

Some problems are common to cutting any government’s spending. Ironclad job security for union employees with seniority means cuts are skewed disproportionately to junior staff still on probation, with the regrettable side effect of denying an injection of fresh blood into a sclerotic workforce. Cutting employees and not programs makes it easier for higher staffing to resume: as documented by Carleton University Professor Ian Lee in How Ottawa Spends, even prolonged bouts of austerity do not derail government spending from long-term trend of higher growth. Across the board cuts do not allow for the surgical removal of redundant or inefficient programs and poor performing employees.

Canada has some unique problems with federal government spending. Savoie documents how 41 per cent of federal civil servants are located in Ottawa, versus 16 per cent in Washington and 19 per cent in London, despite Canada having the most decentralized federation in the G7. The concentration in Ottawa partly reflects the exceptional influence exerted by central agencies on all departments. As well, University of Cambridge Professor Dennis Grube found Canada’s civil service was the most resistant to public scrutiny and the most risk adverse in a comparative study of public servants in the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Canada’s federal employees are among the most expensive anywhere. The average civil servant costs taxpayers $146,500 a year including all salary, benefits and costs such as computers and training. Multiplying this average cost by 366,316 federal employees yields a total labour bill of $53.7 billion, not including other spending such as $17.8 billion on consultants. All the recent increase in the ranks of the civil service happened in Justin Trudeau’s tenure, expanding 38.5 per cent after Stephen Harper had cut them 9 per cent between 2010 and 2015 in his determination to balance the budget.

While the cost of government employees has risen sharply, the services they provide to the public are dwindling as government spending increasingly is devoted to managing its unwieldy and bloated bureaucracy. As Savoie observes, unions like to paint civil servants as providing essential services such as food inspectors and rescue workers, when in reality most are involved in a vast web of “policy, coordination, liaison, and performance evaluation units.” The fastest growing occupations in the federal government are in administrative services and program administration, whose share of jobs rose from 25.1 per cent in 2010 to 31.9 per cent in 2023 according to the latest report from the Treasury Board.

A chronic problem is the fierce defense offered by public service unions in “protecting non-performers and insulating the public sector from effective outside scrutiny” as Savoie wrote. The refusal to acknowledge and root out non-performers depresses the morale of the average civil servant who’s unfairly tarred with the reputation of a minority. It also motivates the across-the-board chainsaw approach of DOGE, which critics then decry as not discriminating between good and bad employees. The latter could easily be targeted by senior managers, who know exactly who the non-performers are but cannot be bothered with the years of documentation and bureaucratic headaches needed to get rid of them. The cost of poor performers is substantial; if even 10 per cent of the civil service was eliminated as redundant non-performers, the government would save $5.4 billion a year. Potential savings are likely well over $10 billion.

The federal government potentially has enormous leverage in negotiating civil service pay and getting rid of non-performers, because it can unilaterally change the federal pension plan without negotiating with public-sector unions. The federal pension plan is so generous that it’s referred to as the “golden handcuffs” that tie employees to their jobs irrespective of their pay or working conditions. To protect their lucrative pensions, unions inevitably would be willing to make concessions that substantially lower the burden on Canada’s taxpayers and still improve morale within the civil service.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanadian Police Raid Sophisticated Vancouver Fentanyl Labs, But Insist Millions of Pills Not Destined for U.S.

-

espionage4 hours ago

espionage4 hours agoHong Kong Detains Parents of Activist Frances Hui Amid $1M Bounty, Echoing Election Interference Fears in Canada

-

2025 Federal Election12 hours ago

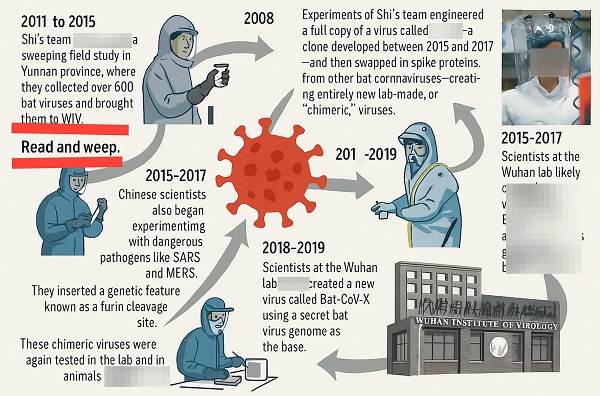

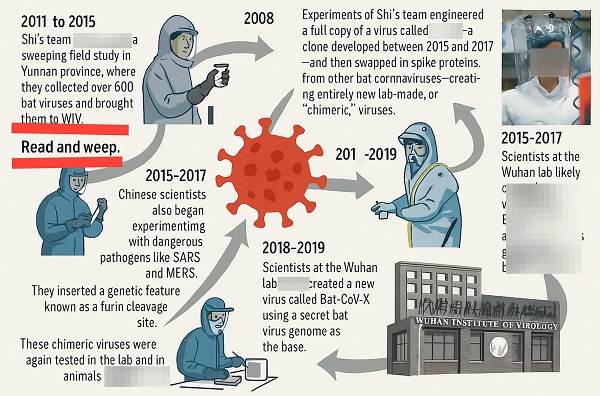

2025 Federal Election12 hours agoBLOCKBUSTER REPORT: Canada’s ties to Wuhan Institute of Virology and creation of COVID uncovered by Sam Cooper of The Bureau

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoTaxpayers urge federal party leaders to drop home sale reporting to CRA

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day ago‘Sadistic’ Canadian murderer claiming to be woman denied transfer to female prison

-

International20 hours ago

International20 hours agoBill Maher Breaks His Silence on His Private Meeting With President Trump

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMusk Slashes DOGE Savings Forecast By 85%

-

Alberta13 hours ago

Alberta13 hours agoProvince introducing “Patient-Focused Funding Model” to fund acute care in Alberta