Crime

Luxury Vancouver Homes at the Center of $100M CAD Loan and Chinese Murder Saga

In a case intertwining toxic loans, a brutal murder, and a court-ordered execution in China, amid the transnational flow of millions into Vancouver’s luxury real estate market, two families are locked in a legal battle over at least five high-end homes in areas of the city reshaped by decades of murky capital flight funneled through underground transfers into Canada’s West Coast.

The plaintiffs’ case, which initially focused on at least eight properties—now reduced to five—alleges that “many millions” worth of real estate was purchased with proceeds from unpaid loans in China and fraudulent transfers into Vancouver real estate.

On November 21, the Supreme Court of British Columbia delivered a procedural ruling allowing the six-year-long Canadian court battle, which includes sordid details such as the slaying of the lender family patriarch in China by the borrower, the now-deceased Long Ni, to continue.

Mr. Ni had promised the lender and his family high returns—up to 50 percent per annum—for providing him funds to invest in Chinese coal mines, the filings say.

Before his death, Changbin Yang, a 54-year-old businessman, had extended two series of loans to Mr. Ni, neither of which had been repaid. The first series, predating 2014, totaled approximately $100 million CAD, including interest. The second involved two loans in April 2017 of about $6 million CAD.

A key detail emerged from a Chinese court ruling in Hubei province. It said Mr. Yang’s claim for massive debt repayments stemmed from a series of promissory notes, culminating in a master promissory note “issued by Mr. Ni to Mr. Yang dated April 8, 2017, three months before Mr. Yang was murdered.”

On July 25, 2017, Mr. Yang was murdered in China at Mr. Ni’s behest. Following the murder, Mr. Ni was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to death by the Chinese courts. After exhausting all appeals, he was executed in 2020.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit are five relatives of Mr. Yang, including his wife, Ms. Liu, and various other family members. Most are permanent residents of Canada living in China. They allege that the murderer’s family are “sitting on property in Vancouver worth many millions of dollars,” the November 2024 B.C. Supreme Court ruling says.

The plaintiffs are seeking judgment against all three defendants—Mr. Ni (now deceased), his wife, Ms. Chen, and his daughter, Ms. Ni—for debt, conversion, and unjust enrichment amounting to approximately $113.5 million CAD.

But Mr. Ni’s family, now living in Vancouver, denies financial ties to the executed borrower and asserts that the court battle is preventing them from selling some of their Canadian properties.

“Ms. Chen and Ms. Ni filed a joint response to the civil claim,” the procedural ruling states, in which “they deny any involvement in, or even knowledge of, the financial transactions between Mr. Yang and Mr. Ni. They plead the allegations of wrongdoing against them ‘are fabrications from start to finish.'”

Filings in the case detail the circumstances under which the murderer’s family settled in Vancouver, apparently four years after Mr. Ni started drawing on loans from his subsequent victim.

In her affidavit dated September 13, 2024, the murderer’s wife described how the family moved to Vancouver in 2011 after she obtained permanent resident status the previous year. She and her husband purchased their matrimonial home on West 33rd Avenue in December 2010 and moved in by March 2011. While Mr. Ni continued working in China, he visited his family in Canada several times a year.

Ms. Chen described their marriage as “a typical relationship in that part of China,” stating that she was a stay-at-home mother while her husband was the family’s breadwinner. She claimed to be aware only in a general sense of what her husband did for a living and, in accordance with her culture, would not “pry into his business affairs.” Ms. Chen also detailed purchasing two rental properties in 2011—on Granville Street and West King Edward Avenue—using money that her husband earned.

The murderer, Mr. Ni, was alive when the lawsuit was initiated and filed a “bare-bones” Response to Civil Claim in December 2018. Following his execution, his counsel withdrew, leaving Ms. Chen and Ms. Ni to face the allegations alone.

Initially, the plaintiffs’ claim targeted “at least” eight properties in Vancouver and Burnaby. They specifically alleged that each of these properties had been purchased by Mr. Ni with the loan proceeds from Mr. Yang and registered, either at the time of purchase or later, in the name of his wife or daughter. However, as the case progressed, doubts arose regarding the true ownership of three properties. The plaintiffs amended their claim to focus on five properties, refining their allegations.

The lawsuit now centers on five properties located across Vancouver’s most exclusive neighborhoods, including Shaughnessy, Kitsilano, Kerrisdale, and West Point Grey—areas renowned for their affluence and skyrocketing home prices.

Notably, West Point Grey is the riding of B.C. Premier David Eby and the neighborhood where Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau once taught at a private school before entering Liberal Party politics. The plaintiffs allege they have traced funds from Mr. Ni’s business activities and alleged crimes in China to these properties.

Commenting on his sympathy toward the plaintiffs—despite long procedural delays in their case—in November 2024, Supreme Court Justice Kent wrote, “The plaintiffs are victims of a horrific crime committed by Mr. Ni.”

Addressing the defendants’ claims of ignorance regarding the murderer’s business activities in Chinese mining, he added, “Although Ms. Chen and Ms. Ni testify in their affidavits that they had no knowledge of Mr. Ni’s business affairs, they do not deny that the money used to purchase the properties registered in their name was supplied by Mr. Ni from his business activities in China.”

Travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic added another layer of complexity. Ms. Liu pointed out that Mr. Ni’s incarceration in China meant he was unable to testify in the British Columbia proceedings, although his testimony was available for the Chinese litigation. She also noted that in 2022, with China’s borders closed, the plaintiffs were uncertain whether they could travel to Canada for the trial.

According to Ms. Liu, the plaintiffs had information suggesting that Mr. Ni had used the loaned funds to invest in coal mines in China. They hoped to enforce the Chinese judgment against these assets before pursuing real estate recovery in Canada.

This case, far from finished, is representative of numerous similar legal battles over Vancouver property, characterized by complex transnational loan arrangements, frequently linked to underground banking and opaque business dealings in China. It underscores the challenges of Canadian courts in mediating massive property dealings involving allegations of transnational financial fraud, sometimes intertwined with violent crime and debt enforcement battles.

As Canada grapples with a housing affordability crisis—issues The Bureau’s investigations suggest are partly linked to international underground banking networks involving China and Middle Eastern states—this case seems emblematic of systemic challenges extending far beyond the dispute between the families of the murdered lender Mr. Yang and the executed borrower Mr. Ni.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Business

China, Mexico, Canada Flagged in $1.4 Billion Fentanyl Trade by U.S. Financial Watchdog

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

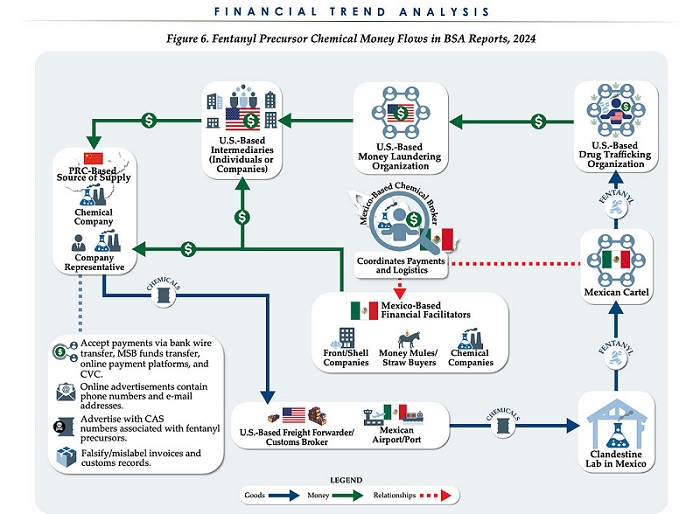

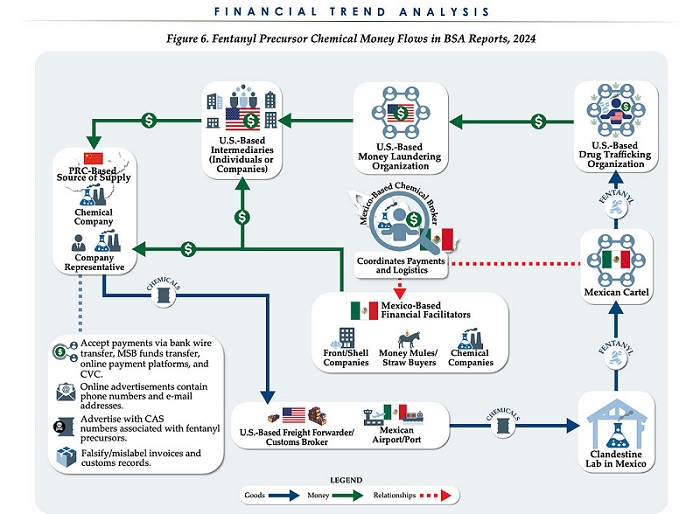

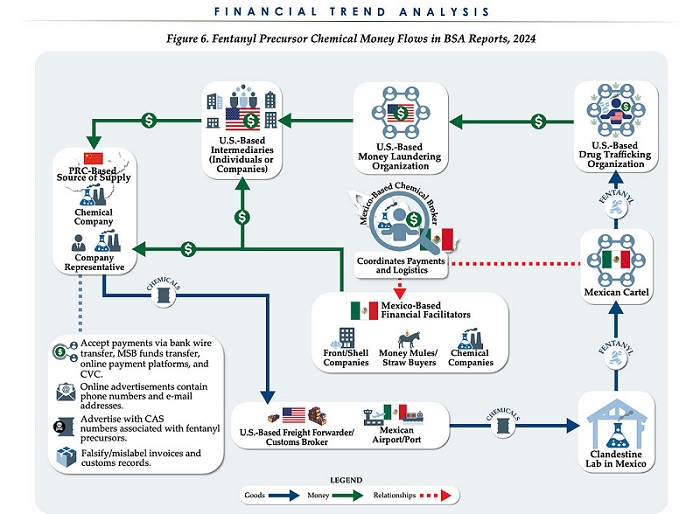

The U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has identified $1.4 billion in fentanyl-linked suspicious transactions, naming China, Mexico, Canada, and India as key foreign touchpoints in the global production and laundering network. The analysis, based on 1,246 Bank Secrecy Act filings submitted in 2024, tracks financial activity spanning chemical purchases, trafficking logistics, and international money laundering operations.

The data reveals that Mexico and the People’s Republic of China were the two most frequently named foreign jurisdictions in financial intelligence gathered by FinCEN. Most of the flagged transactions originated in U.S. cities, the report notes, due to the “domestic nature” of Bank Secrecy Act data collection. Among foreign jurisdictions, Mexico, China, Hong Kong, and Canada were cited most often in fentanyl-related financial activity.

The FinCEN report points to Mexico as the epicenter of illicit fentanyl production, with Mexican cartels importing precursor chemicals from China and laundering proceeds through complex financial routes involving U.S., Canadian, and Hong Kong-based actors.

The findings also align with testimony from U.S. and Canadian law enforcement veterans who have told The Bureau that Chinese state-linked actors sit atop a decentralized but industrialized global fentanyl economy—supplying precursors, pill presses, and financing tools that rely on trade-based money laundering and professional money brokers operating across North America.

“Filers also identified PRC-based subjects in reported money laundering activity, including suspected trade-based money laundering schemes that leveraged the Chinese export sector,” the report says.

A point emphasized by Canadian and U.S. experts—including former U.S. State Department investigator Dr. David Asher—that professional Chinese money laundering networks operating in North America are significantly commanded by Chinese Communist Party–linked Triad bosses based in Ontario and British Columbia—is not explored in detail in this particular FinCEN report.¹

Chinese chemical manufacturers—primarily based in Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Hebei provinces—were repeatedly cited for selling fentanyl precursors via wire transfers and money service businesses. These sales were often facilitated through e-commerce platforms, suggesting that China’s global retail footprint conceals a lethal underground market—one that ultimately fuels a North American public health crisis. In many cases, the logistics were sophisticated: some Chinese companies even offered delivery guarantees and customs clearance for precursor shipments, raising red flags for enforcement officials.

While China’s industrial base dominates the global fentanyl supply chain, Mexican cartels are the next most prominent state-like actors in the ecosystem—but the report emphasizes that Canada and India are rising contributors.

“Subjects in other foreign countries—including Canada, the Dominican Republic, and India—highlight the presence of alternative suppliers of precursor chemicals and fentanyl,” the report says.

“Canada-based subjects were primarily identified by Bank Secrecy Act filers due to their suspected involvement in drug trafficking organizations allegedly sourcing fentanyl and other drugs from traditional drug source countries, such as Mexico,” it explains, adding that banking intelligence “identified activity indicative of Canada-based individuals and companies purchasing precursor chemicals and laboratory equipment that may be related to the synthesis of fentanyl in Canada. Canada-based subjects were primarily reported with addresses in the provinces of British Columbia and Ontario.”

FinCEN also flagged activity from Hong Kong-based shell companies—often subsidiaries or intermediaries for Chinese chemical exporters. These entities were used to obscure the PRC’s role in transactions and to move funds through U.S.-linked bank corridors.

Breaking down the fascinating and deadly world of Chinese underground banking used to move fentanyl profits from American cities back to producers, the report explains how Chinese nationals in North America are quietly enlisted to move large volumes of cash across borders—without ever triggering traditional wire transfers.

These networks, formally known as Chinese Money Laundering Organizations (CMLOs), operate within a global underground banking system that uses “mirror transfers.” In this system, a Chinese citizen with renminbi in China pays a local broker, while the U.S. dollar equivalent is handed over—often in cash—to a recipient in cities like Los Angeles or New York who may have no connection to the original Chinese depositor aside from their role in the laundering network. The renminbi, meanwhile, is used inside China to purchase goods such as electronics, which are then exported to Mexico and delivered to cartel-linked recipients.

FinCEN reports that US-based money couriers—often Chinese visa holders—were observed depositing large amounts of cash into bank accounts linked to everyday storefront businesses, including nail salons and restaurants. Some of the cash was then used to purchase cashier’s checks, a common method used to obscure the origin and destination of the funds. To banks, the activity might initially appear consistent with a legitimate business. However, modern AI-powered transaction monitoring systems are increasingly capable of flagging unusual patterns—such as small businesses conducting large or repetitive transfers that appear disproportionate to their stated operations.

On the Mexican side, nearly one-third of reports named subjects located in Sinaloa and Jalisco, regions long controlled by the Sinaloa Cartel and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación. Individuals in these states were often cited as recipients of wire transfers from U.S.-based senders suspected of repatriating drug proceeds. Others were flagged as originators of payments to Chinese chemical suppliers, raising alarms about front companies and brokers operating under false pretenses.

The report outlines multiple cases where Mexican chemical brokers used generic payment descriptions such as “goods” or “services” to mask wire transfers to China. Some of these transactions passed through U.S.-based intermediaries, including firms owned by Chinese nationals. These shell companies were often registered in unrelated sectors—like marketing, construction, or hardware—and exhibited red flags such as long dormancy followed by sudden spikes in large transactions.

Within the United States, California, Florida, and New York were most commonly identified in fentanyl-related financial filings. These locations serve as key hubs for distribution and as collection points for laundering proceeds. Cash deposits and peer-to-peer payment platforms were the most cited methods for fentanyl-linked transactions, appearing in 54 percent and 51 percent of filings, respectively.

A significant number of flagged transactions included slang terms and emojis—such as “blues,” “ills,” or blue dots—in memo fields. Structured cash deposits were commonly made across multiple branches or ATMs, often linked to otherwise legitimate businesses such as restaurants, salons, and trucking firms.

FinCEN also tracked a growing number of trade-based laundering schemes, in which proceeds from fentanyl sales were used to buy electronics and vaping devices. In one case, U.S.-based companies owned by Chinese nationals made outbound payments to Chinese manufacturers, using funds pooled from retail accounts and shell companies. These goods were then shipped to Mexico, closing the laundering loop.

Another key laundering method involved cryptocurrency. Nearly 10 percent of all fentanyl-related reports involved virtual currency, with Bitcoin the most commonly cited, followed by Ethereum and Litecoin. FinCEN flagged twenty darknet marketplaces as suspected hubs for fentanyl distribution and cited failures by some digital asset platforms to catch red-flag activity.

Overall, FinCEN warns that fentanyl-linked funds continue to enter the U.S. financial system through loosely regulated or poorly monitored channels, even as law enforcement ramps up enforcement. The Drug Enforcement Administration reported seizures of over 55 million counterfeit fentanyl pills in 2024 alone.

The broader pattern is unmistakable: precursor chemicals flow from China, manufacturing occurs in Mexico, Canada plays an increasing role in chemical acquisition and potential synthesis, and drugs and proceeds flood into the United States, supported by global financial tools and trade structures. The same infrastructure that enables lawful commerce is being manipulated to sustain the deadliest synthetic drug crisis in modern history.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Business

Closing information gaps to strengthen Canada’s border security and track fentanyl

By Sean Parker, Dawn Jutla, and Peter Copeland for Inside Policy

To promote better results, we lay out a collaborative approach

Despite exaggerated claims about how much fentanyl is trafficked across the border from Canada to the United States, the reality is that our detection, search, and seizure capacity is extremely limited.

We’re dealing with a “known unknown”: a risk we’re aware of, but don’t yet have the capacity to understand its extent.

What’s more, it may be that the flow of precursor chemicals—ingredients used in the production of fentanyl—is where much of the concern lies. Until we enhance our tracking, search, and seizure capacity, much will remain speculative.

As border security is further scrutinized, and the extent of fentanyl production and trafficking gets brought into sharper focus, the role of the federal government’s Precursor Chemical Risk Management Unit (PCRMU)—announced recently by Health Canada—will become apparent.

Ottawa recently took action to enhance the capabilities of the PCRMU. It says the new unit will “provide better insights into precursor chemicals, distribution channels, and enhanced monitoring and surveillance to enable timely law enforcement action.” The big question is, how will the PCRMU track the precursor drugs entering into Canada that are used to produce fentanyl?

Key players in the import-export ecosystem do not have the right regulatory framework and responsibilities to track and share information, detect suspect activities, and be incentivized to act on it. That’s one of the reasons why we know so little about how much fentanyl is produced and trafficked.

Without proper collaboration with industry, law enforcement, and financial institutions, these tracking efforts are doomed to fail. To promote better results, we lay out a collaborative approach that distributes responsibilities and retools incentives. These measures would enhance information collection capabilities, incentivize system actors to compliance, and better equip law enforcement and border security services for the safety of Canadians.

Trade-off bottleneck: addressing the costs of enhanced screening

To date, it’s been challenging to increase our ability to detect, search, and seize illegal goods trafficked through ports and border crossings. This is due to trade-offs between heightened manual search and seizure efforts at ports of entry, and the economic impacts of these efforts.

In 2024, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) admitted over 93 million travelers. Meanwhile, 5.3 million trucks transported commercial goods into Canada, around 3.6 million shipments arrived via air cargo, nearly 2 million containers were processed at Canadian ports, roughly 1.9 million rail cars carried goods into the country, and about 145.7 million courier shipments crossed the border. The CBSA employs a risk-based approach to border security, utilizing intelligence, behavioral analysis, and random selection to identify individuals or shipments that may warrant additional scrutiny. This triaging process aims to balance effective enforcement with the facilitation of legitimate travel and trade.

Exact percentages of travelers subjected to secondary inspections are not publicly disclosed, but it’s understood that only a small fraction undergo such scrutiny. We don’t learn about the prevalence of these issues through our border screening measures, but in crime reporting data—after it’s too late to avert.

It’s key to have an approach that minimizes time and personnel resources deployed at points of entry. To be effective without being economically disruptive, policymakers, law enforcement, and border security need to strengthen requirements for information gathering, live tracking, and sharing. Legislative and regulatory change to require additional information of buyers and sellers—along with stringent penalties to enforce non-compliance—is a low-cost, logistically efficient way of distributing responsibility for this complex and multifaceted issue. A key concept explored in this paper is strengthening governance controls (“controls”) over fentanyl supply chains through new processes and data digitization, which could aid the PCRMU in their strategic objectives.

Enhanced supply chain controls are needed

When it comes to detailed supply chain knowledge of fentanyl precursor chemicals moving in and out of Canada, regulator knowledge is limited.

That’s why regulatory reform is the backbone of change. It’s necessary to ensure that strategic objectives are met by all accountable stakeholders to protect the supply chain and identify issues. To rectify the issues, solutions can be taken by the PCRMU to obtain and govern a modern fentanyl traceability system/platform (“platform”) that would provide live transparency to regulators.

A fresh set of supply chain controls, integrated into a platform as shown in Fig. 1, could significantly aid the PCRMU in identifying suspicious activities and prioritizing investigations.

Our described system has two distinctive streams: one which leverages a combination of physical controls such as package tampering and altered documentation against a second stream that looks at payment counterparties. Customs agencies, transporters, receivers, and financial institutions would have a hand in ensuring that controls in the platform are working. The platform includes several embedded controls to enhance supply chain oversight. It uses commercially available Vision AI to assess packaging and blockchain cryptography to verify shipment documentation integrity. Shipment weight and quantity are tracked from source to destination to detect diversion, while a four-eyes verification process ensures independent reconciliation by the seller, customs, and receiver. Additionally, payment details are linked to shipments to uncover suspicious financial activity and support investigations by financial institutions and regulators like FINTRAC and FINCEN.

A modern platform securely distributes responsibility in a way that’s cost effective and efficient so as not to overburden any one actor. It also ensures that companies of all sizes can participate, and protects them from exploitation by criminals and reputational damage.

In addition to these technological enhancements and more robust system controls, better collaboration between the key players in the fentanyl supply chain is needed, along with policy changes to incentivize each key fentanyl supply chain stakeholder to adopt the new controls.

Canadian financial institutions: a chance for further scrutiny

Financial institutions (FIs) are usually the first point of contact when a payment is being made by a purchaser to a supplier for precursor chemicals that could be used in the production of fentanyl. It is crucial that they enhance their screening and security processes.

Chemicals may be purchased by wires or via import letters of credit. The latter is the more likely of the two instruments to be used because this ensures that the terms and conditions in the letter of credit are met with proof of shipment prior to payment being released. Payments via wire require less transparency.

Where a buyer pays for precursor chemicals with a wire, it should result in further scrutiny by the financial institution. Requests for supporting documentation including terms and conditions, along with proof of shipment and receipt, should be provided. Under new regulatory policy, buyers would be required to place such supporting documentation on the shared platform.

The less transparent a payment channel is in relation to the supply chain, the more concerning it should be from a risk point of view. Certain payment channels may be leveraged to further mask illicit activity throughout the supply chain. At the onset of the relationship the seller and buyers would link payment information on the platform (payment channel, recipient name, recipient’s bank, date, and payment amount) to each precursor or fentanyl shipment. The supplier, in turn, should record match payment information (payment channel, supplier name, supplier’s bank, date, and payment amount).

Linking payment to physical shipment would enable data analytics to detect irregularities. An irregularity is flagged when the amounts and/or volume of payments far exceed the value of the received goods or vice versa. The system would be able to understand which fentanyl supply chains tend to use a particular set of FIs. This makes it possible to conduct real-time mapping of companies, their fentanyl and precursor shipments and receipts, and the payment institutions they use. With this bigger picture, FIs and law enforcement could connect the dots faster.

Live traceability reporting

Today, suppliers of fentanyl precursors are subject to the Pre-Export Notification Online (PEN Online) database. This database enables governments to monitor international trade in precursor chemicals by sending and receiving pre-export notifications. The system helps prevent the diversion of chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of drugs by allowing authorities to verify the legitimacy of shipments before they occur.

To further strengthen oversight, the platform utilizes immutability technologies—such as blockchain or secure immutable databases—which can be employed to encrypt all shipping documents and securely share them. This presents an auditable form of chain-of-custody and makes any alterations apparent. Customs and buyers would have the capability to verify the authenticity of the originating documents in a way that doesn’t compromise business confidentiality. With the use of these technologies, law enforcement can narrow down their investigations.

An information gap currently exists as the receivers of the shipments don’t share their receipts information with PEN. To strengthen governance on fentanyl supply chains, regulatory policy and legislative changes are needed. The private sector should be mandated to report received quantities of fentanyl or its precursors, as well as suspicious receiving destinations. This could be accomplished on the platform which would embed the receiving process, a reconciliation process of the transaction, the secure upload and sharing of documents, and would be minimally disruptive to business processes.

Additionally, geo-location technology embedded in mobile devices and/or shipments would provide real-time location-based tracking of custody transactions. These geo-controls would ensure accountability across the fentanyl supply chain, in particular where shipments veer off or stop too long on regular shipping routes. Canadian transporters of fentanyl and its precursor chemicals should play an important role in detecting illicit diversion/activities.

Digital labelling

Licensed fentanyl manufacturers could add new unique digital labels to their shipments to get expedited clearance. For example, immutable digital labelling platforms enable tamper-proof digital labels for legitimate fentanyl shipments. This would give pharmacies, doctors, and regulators transparency into the fentanyl’s:

- Chemical composition and concentrations (determining legitimate vs. adulterated versions of the drug)

- Manufacturing facility ID, batch ID, and regulatory compliance status

- Intended buyer authentication (such as licensed pharmaceutical firms or distributors)

Immutable digital labelling platforms offer secure role-based access control. They can display customized data views according to time of day, language, and location. Digital labels could enable international border agencies and law enforcement to receive usable data, allowing legal shipments through faster while triggering closer shipment examinations for those without of a digital label.

International and domestic transporter controls

Transporters act as intermediaries in the supply chain. Their operations could be monitored through a regulatory policy that mandates their participation in the platform for fentanyl and precursor shipments. The platform would support a mobile app interface for participants on-the-move, as well as a web portal and application programming interfaces (APIs) for large-size supply chain participants. Secure scanning of packaging at multiple checkpoints, combined with real-time tracking, would provide an additional layer of protection against fraud, truckers taking bribes, and unauthorized alterations to shipments and documents.

Regulators and law enforcement participation

Technology-based fentanyl controls for suppliers, buyers, and transporters may be reinforced by international customs and law enforcement collaboration on the platform. Both CBSA and law enforcement could log in and view alerts about suspicious activities issued from the FIs, transporters, or receivers. The reporting would allow government personnel to view a breakdown of fentanyl importers, the number of import permit applications, and the amount of fentanyl and its precursors flowing into the country. Responsible regulatory agencies—such as the CBSA and PCRMU—could leverage the reporting to identify hot spots.

The platform would use machine learning to support CBSA personnel in processing an incoming fentanyl or precursor shipment. Machine learning refers to AI algorithms and systems that improve their knowledge with experience. For example, an AI assistant on the traceability system could use machine learning to predict and communicate which import shipments arriving at the border should be passed. It can base these suggestions on criteria like volume, price, origin of raw materials, and origin of material at import point. It can also leverage data from other sources such as buyers, sellers, and banks to make predictions. As an outcome, the shipment may be recommended to pass, flagged as suspicious, or deemed to require an investigation by CBSA.

It’s necessary to keep up to date on new precursor chemicals as the drug is reformulated. Here, Health Canada can play a role, using its new labs and tests—expected as part of the recently announced Canadian Drug Analysis Centre—to provide chemical analysis of seized fentanyl. This would inform which additional chemical supply chains should be tracked in the PCRMU’s collaborative platform, and all stakeholders would widen their scope of review.

These new tools would complement existing cross-border initiatives, including joint U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico crackdowns on illicit drug labs, as well as sovereign efforts. They have the potential to play a vital role in addressing fentanyl trafficking.

A robust, multi-pronged strategy—integrating existing safeguards with a new PCRMU traceability platform—could significantly disrupt the illegal production and distribution of fentanyl. By tracking critical supply chain events and authenticating shipment data, the platform would equip law enforcement and border agencies in Canada, the U.S., and Mexico with timely, actionable intelligence. The human toll demands urgency: from 2017 to 2022, the U.S. averaged 80,000 opioid-related deaths annually, while Canada saw roughly 5,500 per year from 2016 to 2024. In just the first nine months of 2024, Canadian emergency services responded to 28,813 opioid-related overdoses.

Combating this crisis requires more than enforcement. It demands enforceable transparency. Strengthened governance—powered by advanced traceability technology and coordinated public-private collaboration—is essential. This paper outlines key digital controls that can be implemented by global suppliers, Canadian buyers, transporters, customs, and financial institutions. With federal leadership, Canada can spearhead the adoption of proven, homegrown technologies to secure fentanyl supply chains and save lives.

Sean Parker is a compliance leader with well over a decade of experience in financial crime compliance, and a contributor to the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Dawn Jutla is the CEO of Peer Ledger, the maker of a traceability platform that embeds new control processes on supply chains, and a professor at the Sobey School of Business.

Peter Copeland is deputy director of domestic policy at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoTrump Executive Orders ensure ‘Beautiful Clean’ Affordable Coal will continue to bolster US energy grid

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoBREAKING from THE BUREAU: Pro-Beijing Group That Pushed Erin O’Toole’s Exit Warns Chinese Canadians to “Vote Carefully”

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoChina, Mexico, Canada Flagged in $1.4 Billion Fentanyl Trade by U.S. Financial Watchdog

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTamara Lich and Chris Barber trial update: The Longest Mischief Trial of All Time continues..

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoTucker Carlson Interviews Maxime Bernier: Trump’s Tariffs, Mass Immigration, and the Oncoming Canadian Revolution

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoAllegations of ethical misconduct by the Prime Minister and Government of Canada during the current federal election campaign

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoStraits of Mackinac Tunnel for Line 5 Pipeline to get “accelerated review”: US Army Corps of Engineers

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDOGE Is Ending The ‘Eternal Life’ Of Government