Crime

Inside America’s Fastest-Growing Criminal Enterprise: Sex Trafficking

News release from the Free Press

Madeleine Rowley |

Biden’s border policies have led to an explosion in the forced prostitution of migrant boys and girls in the U.S. ‘If I wanted to, I could order a girl within 15 minutes. It’s that easy.’

Lisa slides a Hellcat pistol into her backpack, slinging it over her shoulder. She jumps out of the driver’s seat of her massive Ford F-250 as we head into a barbecue joint for lunch. Steel brass knuckles glint in the console beside a pencil-shaped, pronged object. She sees me looking at it.

“That’s my stabby-stick,” Lisa says before I even ask. “In case I can’t bring my gun somewhere. These guys are dangerous.”

“These guys” are sex traffickers, and dangerous doesn’t begin to describe them.

Many traffickers are members of Mexican or Salvadorian gangs, part of Cuban rings or the vicious Venezuelan group Tren de Aragua. Their modus operandi is luring migrant women and girls across the southern border, promising them good jobs once they get to America, and then forcing them into prostitution once they’re here, ostensibly to pay off the debt they incurred to get into the U.S. Hunting down sex traffickers is not for the faint of heart, and Lisa is not about to take any chances.

An athletic, no-nonsense blonde in her 50s, Lisa runs a small nonprofit foundation called Shepherd’s Watch, dedicated to bringing down sex-trafficking rings. Prior to starting Shepherd’s Watch in 2016, Lisa had been a telecom engineer and an expert at analyzing cell phone data used in court cases. In that job, she says, she saw a “disturbing” amount of child exploitation. “I couldn’t ignore it anymore.”

Lisa, who asked that we not use her real name, calls herself “an informant.” She lacks the authority to arrest a trafficker, and any attempt to rescue the girls herself could well get her killed. Instead, Lisa and a small handful of other Shepherd’s Watch investigators work to locate victims and their pimps and then turn the information over to police departments, sheriff’s offices, and other law enforcement agencies. Because Lisa and her team have gained credibility with law enforcement over the years, the police usually follow up on the information the Shepherd’s Watch informants provide. Sometimes they hit pay dirt, arresting the traffickers and removing the girls to a safe place.

“Law enforcement is understaffed and stretched too thin,” says Lisa. “That’s where we come in.”

At the barbecue joint off Route 75 in Dallas, Lisa pulls out her phone to show me the dozen or so online platforms that traffickers and pimps use to sell girls for sex. The platforms—which include apps like TikTok, OnlyFans, and Facebook—are chockablock with ads of women, usually wearing lingerie, their faces covered to prevent anyone guessing their age. The sheer number of ads is astonishing. “Each week, we track over 12,000 ads for women in Houston, 2,600 in San Antonio, 3,500 in Austin, and 14,000 in Dallas,” says Lisa.

I ask her if the sex trafficking of migrant girls had increased since the Biden administration threw open the border, leading to 8 million migrants crossing the southern border since 2021. “Yes,” she says. “Nearly all of my sex-trafficking rings now are migrant girls. The ads exploded within the first three months of the border being open. We started noticing new sites and ads in Spanish. That was very few before. Then sites dedicated to Latino girls popped up everywhere.” Since the border opened, Lisa added, over 90 percent of the ads are for migrant girls.

|

Many traffickers are members of Mexican or Salvadorian gangs, part of Cuban rings or the vicious Venezuelan group Tren de Aragua. (Robert Gauthier via Getty Images)

“If I wanted to, I could order a girl within 15 minutes,” Lisa says. “It’s that easy.”

And she’s right. After lunch, we drive around the seedier areas of the Dallas suburb of Plano. We’re guided by Jack, an intelligence contractor for Shepherd’s Watch who specializes in geospatial analysis. Jack, who also asked to remain anonymous, works from an office in California. Formerly in law enforcement, he tracks phones using the location data in the background of mobile apps, identifies patterns with cell phone numbers, and does tattoo and facial recognition work. Federal agencies often engage him.

Pretending to be a client, Jack texts a woman on a website called Escort13. She is described as a “new Latina in the city.” The woman tells Jack that she’s at Motel 6 off the North Central Expressway in Plano. Like a scene in a spy movie, Jack relays the information from his California office to Lisa in Texas through the truck’s crackling speakers.

In her profile photo, the woman is dressed in a black, long-sleeve, crop top shirt and short black skirt—modest compared to pictures of some of the other girls that Lisa has shown me. Her dark hair hangs straight below her waist, and her phone covers her face, which conceals her age and identity.

Her profile says she’s 24 years old and that her home base is Philadelphia—neither of which is necessarily true. Gang-led trafficking rings tend to move their victims all over the U.S.; it’s one way they try to stay ahead of the law. So it’s no surprise this young woman is now working out of a motel in Texas. According to Lisa, Latin American girls like her go for anywhere from $130 to $160 per half hour.

After Jack makes contact with the woman, he tells Lisa, “She says to take a photo of the motel’s entrance, and then she’ll give me the room number.” Lisa snaps a photo through the windshield and sends it to Jack, who texts it to the woman and gets the room number. It’s on the second floor of the two-story motel. We drive to the far end of the parking lot, where we have a clear view of the balcony.

A Latina girl pokes her head out the door and cautiously looks around. Realizing no one is there, she retreats inside. A few moments later, a shirtless man throws up the shades in the room directly below her and swivels his head to look around the parking lot.

“That’s probably her pimp or a trafficker,” Lisa says. “Time to go.”

We peel out of the lot and drive to a Studio 6 motel two miles down the road, where Jack is communicating with another migrant girl. This motel doesn’t have balconies, and when Jack asks her to come to the lobby, she says no. We have no choice but to drive away.

Still, it’s been a successful afternoon. With Jack’s help, Lisa has found two possibly sex-trafficked women and one likely trafficker. When Lisa picks me up the following day, she’s on the phone with Plano law enforcement recounting what we saw the day before at the Motel 6.

“She looked young to me,” says Lisa.

In a follow-up phone call, Lisa tells me the police went to the motel to check it out, but the girl was gone. They think she was part of a trafficking ring.

“She’ll resurface,” says Lisa. “They always do.”

|

Gangs lure migrant women across the border with the promise of good jobs, and then force them into prostitution once they arrive. (Illustration by The Free Press, image via Getty)

Deep inside the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services resides a tiny agency called the Office on Trafficking in Persons. A large part of its mission is to help survivors of sex and labor trafficking “rebuild their lives and become self-sufficient.” Among other things, it offers food assistance, medical benefits, and cash to migrant minors who have been trafficked but have managed to escape. Once their eligibility to obtain benefits is approved, they receive a document called the child eligibility letter.

Although the number of child eligibility letters the government issues is supposed to be public information, it became available on the trafficking office’s website only after I filed a Freedom of Information Act request. The numbers confirmed what Lisa had told me: Trafficking has increased—a lot—since Biden took office. During the four years of the Trump administration, the government issued an average of 625 letters per year to migrant minors who had managed to break free from their traffickers.

But in 2021, the first year of the Biden administration, that number jumped to 1,143. In 2022 it jumped again, to 2,226. Last year, the number stood at 2,148, but that was only through September; the fourth quarter hadn’t yet been counted. To put it another way, forced labor and prostitution among underage migrants more than tripled under President Biden, reaching record highs. And that only counted the handful who had escaped—not the thousands who were still held by the traffickers, the ones Lisa was searching for.

“The sex trafficking of minors, and human trafficking as a whole, is one of the fastest-growing criminal enterprises in the U.S.,” said Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent in Charge Mark Dawson after a big bust in Houston last year that saw the arrest of 10 traffickers, all of whom had gang connections.

Sex-trafficking victims often suffer horrific abuse, as I discovered when I spoke to Landon Dickeson, the 36-year-old executive director for Bob’s House of Hope in Denton, Texas, the only shelter for male sex-trafficking victims ages 18 and up in the country. Dickeson says they’ve seen teens from Central and South America who have been so tortured by their traffickers they can barely function.

Dickeson described caring for teens who have brain damage from being so heavily drugged—teens who have had their fingernails pulled out, and lemon juice poured on wounds. When I asked to interview one of their migrant residents, Dickeson said they simply weren’t in any condition to speak to anyone, much less a reporter.

“We think the cartels and gangs use torture as a control method for the males,” said Dickeson. “They’re not going to fight back if they chain their victims to a radiator, beat them up frequently, or drug them.”

The House of Hope residents often come branded or tattooed by the cartels and gangs who trafficked them, and most were cross-victimized—used as drug mules as well as for labor and sex.

Bob Williams, CEO and founder of Bob’s House of Hope, says they receive two to three calls a month to help minor males who have been sex trafficked. “There is not one shelter in the country for 12- to 17-year-olds,” he said. “This is a big problem because they get put in the system and don’t get the help they need.” Williams, who was sexually assaulted as a teen himself, says they’re working on procuring more funding to build a program for minors.

There is no question that the border crisis is the primary reason for the increase in the sex trafficking of migrants. Here’s how it works: When underage migrants cross the border unaccompanied by a family member, they are sent to a temporary holding facility run by one of a number of nonprofit organizations operating at the border. The NGOs are expected to move the migrants out within a couple of weeks because there are so many more coming in right behind them. During the time the migrants are in the holding facility, both the NGOs and the government are supposed to vet the people who will take them when they depart. These people are called sponsors, and the vast preference of everyone in the system is that they be relatives already living in the U.S.

But sometimes an underage migrant doesn’t have a family sponsor, which gives the cartels and gangs their opening. They pretend to be legitimate sponsors, and with the pressure on the NGOs and the government to move the migrants through the system quickly, gang members—who usually have their hooks into the migrant well before they’ve crossed the border—are accepted as sponsors.

How do they get away with this? They fill out applications in illegible handwriting, guessing (often correctly) that no one will look at it closely. They coach the girl or boy to say that their sponsor is a cousin or an uncle. And they take advantage of the fact that the federal agency overseeing migrant relocation, the Office of Refugee Resettlement—or ORR—is notoriously negligent in vetting sponsors.

For instance, the ORR is supposed to send fingerprints of nonfamily sponsors to the FBI to see if they have a criminal record, and to do background checks for child abuse or neglect. But earlier this year, the Department of Health and Human Services’ inspector general conducted a study of 343 randomly chosen minors to see if their sponsors had been vetted properly. Their findings, issued in February, concluded that 19 percent of the children were released to sponsors before the fingerprint and background checks were completed—meaning that criminals could well have taken migrant children without the government realizing it.

In July, Republican senator Chuck Grassley hosted a roundtable on the trafficking crisis at the border. Tara Rodas, 55, a federal employee who in 2021 worked at an emergency intake shelter in California, testified that while she was there, a 13-year-old girl from El Salvador was released to a sponsor in Ohio who was affiliated with the MS-13 gang.

In an email Rodas sent to a colleague at the time, which was released by Grassley, she wrote that “our team discovered that human traffickers are exploiting the HHS Unaccompanied Children. ‘Bad actors’ are recruiting, harboring, and transporting minors; using force, fraud, and coercion; for the purpose of involuntary servitude, debt bondage, slavery, and potentially commercial sex.”

Deborah White, another whistleblower who worked at the same shelter, testified that migrant children were handed over to improperly vetted sponsors who used fraudulent IDs and different addresses to procure numerous unrelated children. “I had multiple cases that I reported on,” said White, meaning she reported suspicious sponsors to her supervisor. “One in particular where we sent 329 children to one address: two garden apartment [buildings] in Houston, Texas.” The supervisor, White told The Free Press in an interview, took no steps to investigate further, but instead told White that she wasn’t moving migrants out of the facility quickly enough.

Washington’s lack of interest in the sex-trafficking crisis is stunning. Sometimes it seems as though the only person in a position of power who cares about the issue is 91-year-old Senator Grassley. And he has been as passionate about it when Trump was president as he is now, during Biden’s presidency.

“I’ve been trying to protect unaccompanied children that are put in dangerous environments,” he told me in an interview. “These are the most vulnerable people, and somebody’s got to look out for them, and that’s me.”

As far back as 2014, when “just” 57,000 unaccompanied children crossed the border—less than half the current number—Grassley sounded the alarm that the Office of Refugee Resettlement was having trouble accommodating so many migrant children.

The next year, he wrote a letter to the Department of Homeland Security, saying that up to 3,400 unaccompanied children’s sponsors had criminal histories. Two years later, he urged the ORR to take responsibility for unaccompanied children who had ties to the gang. “Your agencies repeatedly pass the buck to each other. As a result, children are allowed to disappear. When these children disappear without any supervision, they are vulnerable to join dangerous gangs like MS-13,” he said.

Grassley reached across the aisle in 2019 and 2021, working with Democratic senators Dianne Feinstein and Ron Wyden, respectively, regarding allegations of sexual abuse and employee misconduct at ORR-funded shelters. Grassley and Wyden’s investigation found that between 2016 and 2020, ORR received nearly 7,500 reports of sexual misconduct involving an unaccompanied child staying at a shelter. Wyden attributed this to “years of mismanagement and poor oversight” by ORR.

With the election of Joe Biden—and the border crisis that ensued—other Republicans have jumped on the trafficking bandwagon, but Grassley has continued to lead the charge, using his staff to conduct significant investigations. In January, for instance, he sent a detailed letter to Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas and FBI Director Christopher Wray, detailing evidence his staff had uncovered of unaccompanied children who were suspected of being in the hands of traffickers.

Democrats have been shamefully silent on the trafficking issue. At the roundtable Grassley held in July, not a single Democrat attended. Neither did Mayorkas. “Democrats didn’t come because they’re just too embarrassed to talk about the shortcomings of this administration on immigration,” Grassley told me. “Especially when you have HHS sending kids to MS-13 gang-related sponsors in Ohio. It’s hard to explain that.”

As for the Office of Refugee Resettlement, its track record remains abysmal. It has yet to do anything to reduce the sex trafficking that is taking place under its nose. On the contrary, it has lately been pushing through rules that will minimize the vetting of sponsors—for instance, making background checks optional instead of mandatory. This, of course, will allow the NGOs to push migrant children through the system even faster. But it will also make it easier for gangs and criminals to “sponsor” migrant girls after they’ve crossed the border. Grassley is trying to stop that from happening, but with the Democrats in control of the Senate, it’s an uphill fight.

That gangs are sex trafficking women and girls who cross the border—and that the Office of Refugee Resettlement is making it so easy for them—is an open secret to everyone who is part of the system. One proof point: An NGO operating at the border, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, started a program in 2022 specifically aimed at helping trafficked kids. Naturally, it is paid for by the Biden administration. Indeed, like all the NGOs at the border, the organization gets well over 95 percent of its revenue from the Office of Refugee Resettlement, in its case $292 million. Of that amount, $60 million goes to caring for unaccompanied children, including trafficked children, according to its 2023 federal filing.

The initiative for trafficked migrants is called the Aspire program. Aspire uses subcontractors to connect migrant children with immigration lawyers, food, clothing, and medical services. It also helps them get child eligibility letters so they’ll qualify for cash, which ranges from about $1,000 to $6,000, depending on the child’s needs and where they live.

Leah Breevoort, a supervisor for the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants trafficking services department, told me that most of the children whose cases they manage represent the most extreme cases of trafficking. The Aspire program currently has 767 migrants, all of whom have child eligibility letters. Rather matter-of-factly, she said she had seen cases in which the sponsor was trafficking a child, or when “the child has a debt from their travel journey, and therefore are working to pay off that debt.”

Once the children are released from the temporary shelters, they’re no longer the federal government’s responsibility, so even kids with child eligibility letters wind up having to fend for themselves. “We try to find a safe placement for that minor,” said Breevoort. “Sometimes it’s a homeless runaway shelter or another migrant shelter. But it’s really, really difficult.”

Immigration lawyer Emma Hetherington, the director of the Wilbanks Child Endangerment and Sexual Exploitation (CEASE) Clinic at the University of Georgia School of Law, also confirmed that some of the migrant children she’s worked with were sex trafficked by their sponsors or by another adult living in the same home.

At CEASE, Hetherington has seen an overlap with migrant children who were trafficked for both labor and sex. “This is a very vulnerable population,” she said. “They’re easier to manipulate because their basic needs aren’t being met. These kids did not and cannot consent to being trafficked.”

|

A California Border Patrol agent processes migrants after they crossed into the U.S. from Mexico near Jacumba, California. (Qian Weizhong via Getty Images)

With the federal government mostly looking the other way, it falls to people like Lisa and local law enforcement to bust up sex-trafficking rings. And there have been some success stories.

In March, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department rescued a teen girl and four other women who were being held in a house in the suburbs near a golf course by a sex-trafficking ring run by the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

In April, police in Socorro, Texas, near El Paso, raided a house where seven young girls were being sex trafficked. “We’re here to rescue those that otherwise might not have a voice,” said Chief David Burton at the time.

In May, the East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff’s Office in Louisiana busted a sex-trafficking ring run by Tren de Aragua. There were up to 30 victims who were allegedly stashed in homes throughout Virginia, Louisiana, Texas, and Florida.

In August, the San Antonio Police Department, aided by Homeland Security, arrested two Venezuelan illegal immigrants for sex trafficking two women. The alleged traffickers forced the women to work up to 20 hours a day providing sexual services, under the threat of violence. The suspected traffickers took 60 percent of the money.

One law enforcement official who has focused on sex trafficking is Sheriff Grady Judd of Polk County, Florida. His experience is proof that something can be done about trafficking if law enforcement makes it a priority. The Polk County Sheriff’s Department frequently conducts operations in which, like Lisa and Jack, investigators pose online as clients to locate potential victims.

Their largest bust to date, which took place last March, yielded 228 arrests, with 13 potential trafficking victims rescued—10 of whom were migrants.

Although most of those arrested were “johns,” Judd’s office also nabbed several dozen traffickers, most of whom were illegal immigrants from Chile, Cuba, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. Since the bust, trafficking in Polk County has decreased, Judd told me.

“Traffickers think, ‘We’re not going to Polk County. We know what happened there. That sheriff don’t play,’ ” Judd said.

In many of my interviews, people told me that trafficking has become so widespread that I could find it anywhere in the country. I was skeptical about these claims, but Lisa wasn’t.

“I’ll show you,” she says one morning after filling her tank with gas. She pulls up a website on her phone—its tagline is “Where Fantasy Meets Reality”—and clicks on the profile of a foot spa in Dallas. In the description, the masseuse is described as “Asian, Chinese,” and it’s cash only, with a 60-minute massage priced at $60.

We drive into a strip mall and park in front of the foot spa. The business’s windows are tinted, making it impossible to see inside. There’s a hair salon next door, and a mother holds her toddler’s hand as they walk toward an adjacent grocery store. We watch as men enter and exit the spa.

We decide to enter ourselves, and the first thing I see are five security cameras trained on us. The front desk is unmanned, and there’s a small waiting area with a couch to the left. After a few minutes, a woman slowly opens a door that separates the front entryway from the massage area. Her bright pink silk robe hangs open, revealing black lingerie underneath.

“Do you have gift cards?” Lisa asks—pretending she wants to buy one for a male friend.

The woman looks confused and shakes her head, shooting us a furtive glance before closing the door.

Back in the truck, Lisa explains that there are sex-trafficking rings being run out of illicit massage parlors—basically brothels—all over the country.

After I return to my home near Baltimore, Maryland, I go online to see if there are any illicit massage parlors and foot spas near me.

I found one two miles away.

Madeleine Rowley is an investigative reporter. Follow her on X @Maddie_Rowley, and read her piece “Nonprofits Are Making Billions off the Border Crisis.”

Reports like this one require time and resources. To support more of our independent journalism, become a Free Press subscriber today:

Crime

Brown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

From The Center Square

By

Rhode Island officials said the suspected gunman in the Brown University mass shooting has been found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, more than 50 miles away in a storage facility in southern New Hampshire.

The shooter was identified as Claudio Manuel Neves-Valente, a 48-year-old Brown student and Portuguese national. Neves-Valente was found dead with a satchel containing two firearms inside in the storage facility, authorities said.

“He took his own life tonight,” Providence police chief Oscar Perez said at a press conference, noting that local, state and federal law officials spent days poring over video evidence, license plate data and hundreds of investigative tips in pursuit of the suspect.

Perez credited cooperation between federal state and local law enforcement officials, as well as the Providence community, which he said provided the video evidence needed to help authorities crack the case.

“The community stepped up,” he said. “It was all about groundwork, public assistance, interviews with individuals, and good old fashioned policing.”

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha said the “person of interest” identified by private videos contacted authorities on Wednesday and provided information that led to his whereabouts.

“He blew the case right open, blew it open,” Neronha said. “That person led us to the car, which led us to the name, which led us to the photograph of that individual.”

“And that’s how these cases sometimes go,” he said. “You can feel like you’re not making a lot of progress. You can feel like you’re chasing leaves and they don’t work out. But the team keeps going.”

The discovery of the suspect’s body caps an intense six-day manhunt spanning several New England states, which put communities from Providence to southern New Hampshire on edge.

“We got him,” FBI special agent in charge for Boston Ted Docks said at Thursday night’s briefing. “Even though the suspect was found dead tonight our work is not done. There are many questions that need to be answered.”

He said the FBI deployed around 500 agents to assist local authorities in the investigation, in addition to offering a $50,000 reward. He says that officials are still looking into the suspect’s motive.

Two students were killed and nine others were injured in the Brown University shooting Saturday, which happened when an undetected gunman entered the Barus and Holley building on campus, where students were taking exams before the holiday break. Providence authorities briefly detained a person in the shooting earlier in the week, but then released them.

Investigators said they are also examining the possibility that the Brown case is connected to the killing of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor in his hometown.

An unidentified gunman shot MIT professor Nuno Loureiro multiple times inside his home in Brookline, about 50 miles north of Providence, according to authorities. He died at a local hospital on Tuesday.

Leah Foley, U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, was expected to hold a news briefing late Thursday night to discuss the connection with the MIT shooting.

Crime

Bondi Beach Survivor Says Cops Prevented Her From Fighting Back Against Terrorists

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

A woman who survived the Hanukkah terrorist attack at Bondi Beach in Australia said on Monday that police officers seemed less concerned about stopping the attack than they were about keeping her from fighting back.

A father and son of Pakistani descent opened fire on a Hanukkah celebration Sunday, killing at least 15 people and wounding 40, with one being slain on the scene by police and the other wounded and taken into custody. Vanessa Miller told Erin Molan about being separated from her three-year-old daughter during Monday’s episode of the “Erin Molan Show.”

“I tried to grab one of their guns,” Miller said. “Another one grabbed me and said ‘no.’ These men, these police officers, they know who I am. I hope they are hearing this. You are weak. You could have saved so many more people’s lives. They were just standing there, listening and watching this all happen, holding me back.”

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

WATCH:

“Two police officers,” Miller continued. “Where were the others? Not there. Nobody was there.”

New South Wales Minister of Police Yasmin Catley did not immediately respond to a request for comment from the Daily Caller News Foundation about Miller’s comments.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese vowed to enact further restrictions on guns in response to the attack at Bondi Beach, according to the Associated Press. The new restrictions would include a limit on how many firearms a person could own, more review of gun licenses, limiting the licenses to Australian citizens and “additional use of criminal intelligence” to determine if a license to own a firearm should be granted.

Sajid Akram, 50, and Naveed Akram, 24, reportedly went to the Philippines, where they received training prior to carrying out the Sunday attack, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Naveed Akram’s vehicle reportedly had homemade ISIS flags inside it.

Australia passed legislation that required owners of semi-automatic firearms and certain pump-action firearms to surrender them in a mandatory “buyback” following a 1996 mass shooting in Port Arthur, Tasmania, that killed 35 people and wounded 23 others. Despite the legislation, one of the gunmen who carried out the attack appeared to use a pump-action shotgun with an extended magazine.

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Business24 hours ago

Business24 hours agoMainstream media missing in action as YouTuber blows lid off massive taxpayer fraud

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoLand use will be British Columbia’s biggest issue in 2026

-

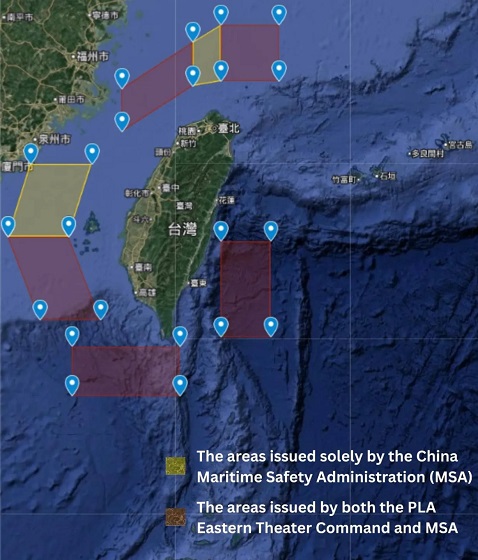

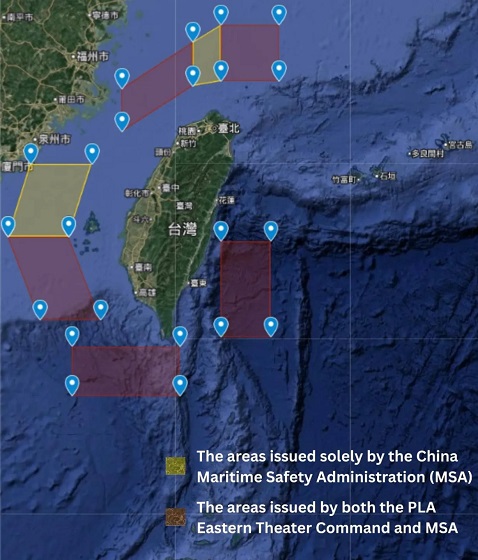

International14 hours ago

International14 hours agoChina Stages Massive Live-Fire Encirclement Drill Around Taiwan as Washington and Japan Fortify

-

Haultain Research2 days ago

Haultain Research2 days agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Digital ID13 hours ago

Digital ID13 hours agoThe Global Push for Government Mandated Digital IDs And Why You Should Worry

-

Energy15 hours ago

Energy15 hours agoRulings could affect energy prices everywhere: Climate activists v. the energy industry in 2026