Indigenous

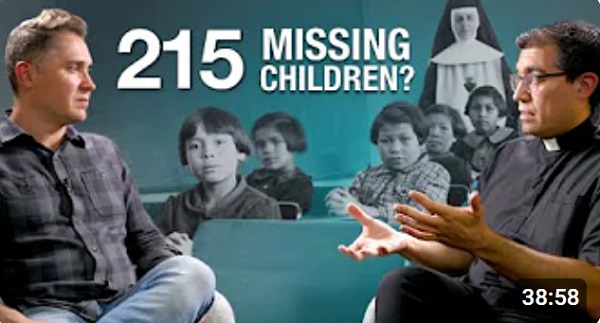

Indigenous Catholic Priest questions “The murder of 215 Indigenous Children” at Kamloops Indian Residential School

From the podcast Catholic Minute With Ken & Janelle

Indigenous Catholic priest, Fr. Cristino Bouvette, speaks to the report of the 215 missing children first released in 2021 and what we know today.

On May 27, 2021, the Kamloops Indian Band announced that ground-penetrating radar had detected the remains of 215 “missing children” at the site of a former residential school. The media quickly picked up the story, with headlines proclaiming the discovery of “mass graves.” Social media exploded. Churches were vandalized, and some were set on fire. Catholic Bishops issued apologies. But was it true?

Fr. Cristino Bouvette, a Catholic priest with Indigenous heritage, brings clarity to the controversy.

Full statement of first statement by Kamloops Indian Band, on May 2021 https://tkemlups.ca/wp-content/upload…

Updated Statement: May, 2024 on 215 anomalies were detected https://tkemlups.ca/offices-closed-on…

Canada mourns as remains of 215 children found at indigenous school https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-can…

Kamloops Indian Residential School Mass Graves: No Bodies Found Despite $8 Million Probe https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/India/…

Terry Glavin: Canada slowly acknowledging there never was a ‘mass grave’ https://nationalpost.com/opinion/terr…

Please consider supporting our work here: https://kenandjanelle.com/

Canadian Energy Centre

Saskatchewan Indigenous leaders urging need for access to natural gas

Piapot First Nation near Regina, Saskatchewan. Photo courtesy Piapot First Nation/Facebook

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Cody Ciona and Deborah Jaremko

“Come to my nation and see how my people are living, and the struggles that they have day to day out here because of the high cost of energy, of electric heat and propane.”

Indigenous communities across Canada need access to natural gas to reduce energy poverty, says a new report by Energy for a Secure Future (ESF).

It’s a serious issue that needs to be addressed, say Indigenous community and business leaders in Saskatchewan.

“We’re here today to implore upon the federal government that we need the installation of natural gas and access to natural gas so that we can have safe and reliable service,” said Guy Lonechild, CEO of the Regina-based First Nations Power Authority, on a March 11 ESF webinar.

Last year, 20 Saskatchewan communities moved a resolution at the Assembly of First Nations’ annual general assembly calling on the federal government to “immediately enhance” First Nations financial supports for “more desirable energy security measures such as natural gas for home heating.”

“We’ve been calling it heat poverty because that’s what it really is…our families are finding that they have to either choose between buying groceries or heating their home,” Chief Christine Longjohn of Sturgeon Lake First Nation said in the ESF report.

“We should be able to live comfortably within our homes. We want to be just like every other homeowner that has that choice to be able to use natural gas.”

At least 333 First Nations communities across Canada are not connected to natural gas utilities, according to the Canada Energy Regulator (CER).

ESF says that while there are many federal programs that help cover the upfront costs of accessing electricity, primarily from renewable sources, there are no comparable ones to support natural gas access.

“Most Canadian and Indigenous communities support actions to address climate change. However, the policy priority of reducing fossil fuel use has had unintended consequences,” the ESF report said.

“Recent funding support has been directed not at improving reliability or affordability of the energy, but rather at sustainability.”

Natural gas costs less than half — or even a quarter — of electricity prices in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, according to CER data.

“Natural gas is something NRCan [Natural Resources Canada] will not fund. It’s not considered a renewable for them,” said Chief Mark Fox of the Piapot First Nation, located about 50 kilometres northeast of Regina.

“Come to my nation and see how my people are living, and the struggles that they have day to day out here because of the high cost of energy, of electric heat and propane.”

According to ESF, some Indigenous communities compare the challenge of natural gas access to the multiyear effort to raise awareness and, ultimately funding, to address poor water quality and access on reserve.

“Natural gas is the new water,” Lonechild said.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

John Rustad’s Residential School Claim Is False And Dangerous

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

When politicians misrepresent facts or historical events, whether out of ignorance or political expediency, they do a disservice to the truth and public trust. On Feb. 24, 2025, B.C. Conservative Party Leader John Rustad reportedly told Global News that “more than 4,000 children did not return home” from residential schools because “those children died in residential schools.” As researcher Nina Green points out, this statement is demonstrably false and contradicts the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) final report.

Sadly, Rustad is not the only one making such claims. Similar statements, portrayed as facts, are repeated by politicians who should know better.

The truth, according to the TRC, is that 423 named children died on the premises of residential schools between 1867 and 2000. That is a tragedy, and we must expand our understanding of how and why these deaths occurred. To learn from tragedies, we must acknowledge and reflect on them. But to truly understand, we must accept what is true rather than bending or distorting it. Repeating the claim that “more than 4,000” children died in residential schools, as Rustad and others have uncritically reported, misrepresents reality.

The vastly inflated number, according to Green, originates from the University of Manitoba’s National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), which has misrepresented the data by including children who died after leaving school—in hospitals, in accidents at home, and even well into adulthood. This distortion has led to widespread misrepresentation, misleading policymakers and the public.

Why does this matter?

Canada’s history with Indigenous residential schools is deeply painful. Abuses, neglect and forced assimilation were real in many instances. However, distorting the facts about residential school deaths promotes a false narrative of genocide that does not serve justice—in fact, this false narrative undermines it. If reconciliation means anything, it must be built on truth, not contrived political narratives.

By repeating the claim that more than 4,000 children died at residential schools, Rustad is spreading falsehoods and stoking division. This figure has been used to justify claims of mass graves, leading to international headlines and widespread outrage that harm present generations of Indigenous people. Yet, nearly four years after the first claims of unmarked graves, no remains have been excavated or verified.

Rustad is not a private citizen—he is a public figure whose words carry weight. As such, he is responsible for ensuring that the information he disseminates is accurate. Rustad is failing in his duty to the public. Depending on his motivation, he contributes to a culture in which historical accuracy is sacrificed for political expediency.

Some may argue that the exact number of students who died at residential schools is not important. But truth is not negotiable. If we accept exaggerated claims in one instance, we set a dangerous pattern for historical distortions. The truth should not be ideological or political.

If Rustad is serious about Indigenous issues, he should demand transparency from the University of Manitoba and its NCTR. Instead of accepting misleading figures, he should call for the full release of the TRC records, as was promised in 2013.

Leaders like Rustad must be held accountable. Falsehoods, no matter how well-intentioned, do not advance reconciliation. They erode trust, divide Canadians, and ultimately undermine the cause they claim to support. All Canadians deserve much better.

Marco Navarro-Genie is the vice president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. With Barry Cooper, he is coauthor of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoRCMP memo warns of Chinese interference on Canadian university campuses to affect election

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoResearchers Link China’s Intelligence and Elite Influence Arms to B.C. Government, Liberal Party, and Trudeau-Appointed Senator

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoThe status quo in Canadian politics isn’t sustainable for national unity

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoPoilievre Announces Plan To Cut Taxes By $100,000 Per Home

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoScott Bessent Says Trump’s Goal Was Always To Get Trading Partners To Table After Major Pause Announcement

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoTwo Canadian police unions endorse Pierre Poilievre for PM

-

2025 Federal Election23 hours ago

2025 Federal Election23 hours agoCarney needs to cancel gun ban and buyback

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoStocks soar after Trump suspends tariffs