Economy

Hydrocarbons Are The Backbone of Global Progress

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

The use of hydrocarbons is a necessity for modern life.

Climate Crusaders claim that our society could do without oil and natural gas by proceeding to a Utopia of ‘Net Zero’ by 2050, extracting CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions from the atmosphere. However, as the Canadian Energy Centre notes, that cherished goal cannot be realized. This is true of fueling transport, heating or electric power, and all other uses of hydrocarbon fossil fuels.

People use oil and natural gas constituents for more than just burning. They use them in every sector of the economy, including military equipment and non profit organizations such as universities and hospitals.

The main component is ethane, C2H6, a ‘natural gas liquid’, extracted from raw natural gas. Ethane is then converted to ethylene, a versatile building block for many other chemicals, Other natural gas liquids, such as propane and butane, are generally used as fuel, in petrochemical production, and as some oil components.

Ethylene is used in various plastics, textiles, detergents and antifreeze. Plastics are used for containers, in countless household and industrial products, and tubing, filters, surgical masks, gloves, gowns, bandages, disinfectants and other medical products. Petrochemical-sourced materials are in the outer casing of medical devices and their components– important instruments such as blood diagnostics machines, DNA sequencers, MRI devices, ultra-sound and CAT and PET scanners.

Styrene, an ethylene end-product, makes synthetic rubber in tires. Synthetic rubber and related products are vital for the gaskets, seals, hoses and tubes in internal combustion, jet and diesel engines. Diesel engines are used in long-distance trucks bringing food to supermarkets. They also power excavating equipment that mines ores to refine into metals, fire trucks, and other machines, such as combines and tractors, which are vital to agriculture.

Petrochemicals also go into polymer fabrics such as polyester, spandex, acrylic and ‘breathable’ fabrics used by themselves or with ‘natural’ materials such as wool, cotton, silk and linen to make a great variety of items like clothes, underclothes, athletic wear, waterproof or winter jackets, hosiery, belts, handbags, upholstery material, furniture coverings, lawn and garden furniture, slope-stabilizing geotechnical fabrics, retractable arenas’ roof coverings, bedding materials, curtains, drapes, and tablecloths.

The same for the construction industries. Such products include paints, solvents, lacquers, countertops, knobs, flooring, adhesives, abrasives, pipes, plumbing and lighting fixtures. Two major insulation products builders and renovators are compelled to add to homes and office buildings make use of petrochemicals: polyurethane foam and styrofoam. Plastics go into the insulation’s outer sheath and for house wrap.

Plastics and related synthetic materials are also used in the latest generation of high-insulation windows, solar panels and wind turbines. Hence, petroleum based products are crucial to climate crusaders’ goal of lower energy consumption.

Plastics indeed add to the garbage volumes people generate. But plastic trash is manageable. Current recycling programs are ineffective, says the journal Nature. Despite rampant alarmism, waste-to-energy plastic destruction, as is bacterial digestion, is a viable alternative.

Petrochemicals and plastics make modern life possible. While substitutes are now under development, they are unlikely to become common anytime soon. So forbidding plastics would be detrimental, especially for emerging economies. Petrochemicals and plastics derived from hydrocarbons are crucial to making less-developed nations healthy and prosperous. Depriving them of that opportunity would be cruel and unnecessary.

Ian Madsen is the Senior Policy Analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Business

Canada Hits the Brakes on Population

The population drops for the first time in years, exposing an economy built on temporary residents, tuition cash, and government debt rather than real productivity

Canadians have been told for years that population decline was unthinkable, that it was an economic death spiral, that only mass immigration could save us. That was the line. Now the numbers are in, and suddenly the people who said that are very quiet.

Statistics Canada reports that between July 1 and October 1, 2025, Canada’s population fell by 76,068 people, a decline of 0.2 percent, bringing the total population to 41,575,585. This is not a rounding error. It is not a model projection. It is an official quarterly population loss, outside the COVID period, confirmed by the federal government’s own data

The reason matters. This did not happen because Canadians suddenly stopped having children or because of a natural disaster. It happened because the number of non‑permanent residents dropped by 176,479 people in a single quarter, the largest quarterly decline since comparable records began in 1971. Permit expirations outpaced new permits by more than two to one. Outflows totaled 339,505, while inflows were just 163,026

That is the so‑called growth engine shutting down.

Permanent immigration continued at roughly the same pace as before. Canada admitted 102,867 permanent immigrants in the quarter, consistent with recent levels. Births minus deaths added another 17,600 people. None of that was enough to offset the collapse in temporary residency. Net international migration overall was negative, at minus 93,668

And here’s the part you’re not supposed to say out loud. For the Liberal‑NDP government, this is bad news. Their entire economic story has rested on population‑driven GDP growth, not productivity. Add more people, claim the economy is growing, borrow more money, and run the national credit card a little harder. When population growth reverses, that illusion collapses. GDP per capita does not magically improve. Housing shortages do not disappear. The math just stops working.

The regional numbers make that clear. Ontario’s population fell by 0.4 percent in the quarter. British Columbia fell by 0.3 percent. Every province and territory lost population except Alberta and Nunavut, and even Alberta’s growth was just 0.2 percent, its weakest since the border‑closure period of 2021

Now watch who starts complaining first. Universities are already bracing for it. Study permit holders alone fell by 73,682 people in three months, with Ontario losing 47,511 and British Columbia losing 14,291. These are the provinces with the largest university systems and the highest dependence on international tuition revenue

You’re going to hear administrators and activists say this is a crisis. What they mean is that fewer students are paying international tuition to subsidize bloated campuses and programs that produce no measurable economic value. When the pool of non‑permanent residents shrinks, departments that exist purely because enrollment was artificially inflated start to disappear. That’s not mysterious. That’s arithmetic.

For years, Canadians were told that any slowdown in population growth was dangerous. The truth is more uncomfortable. What’s dangerous is building a national economic model on temporary residents, borrowed money, and headline GDP numbers while productivity stagnates. The latest StatsCan release doesn’t just show a population decline. It shows how fragile the story really was, and how quickly it unravels when the numbers stop being padded.

Subscribe to The Opposition with Dan Knight

Business

White House declares inflation era OVER after shock report

The White House on Thursday declared a decisive turn in the inflation fight, pointing to new data showing core inflation has fallen to its lowest level in nearly five years — a milestone the administration says validates President Donald Trump’s economic reset after inheriting what it calls a historic cost-of-living crisis from the Biden era. In a statement accompanying the report, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said inflation “came in far lower than market expectations,” drawing a sharp contrast with the 9 percent peak under President Joe Biden and arguing the numbers reflect sustained relief for American households. “Core inflation is at a new multi-year low, as prices for groceries, medicine, gas, airfare, car rentals, and hotels keep falling,” Leavitt said, adding that lower prices and rising paychecks are expected to continue into the new year.

According to the White House, core inflation — widely viewed by economists as the most reliable gauge because it strips out volatile food and energy costs — is now down roughly 70 percent from its Biden-era high. Officials noted that if inflation continues at the pace of the last two months, it would be running at an annualized rate of about 1.2 percent, well below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. The report also highlighted broad-based price moderation across consumer staples and services, with declines in groceries, dairy, fruits and vegetables, prescription drugs, clothing, airfares, natural gas, car and truck rentals, and hotel prices. Average gas prices have fallen to multi-year lows, while rent inflation has dropped to its lowest level since October 2021, a shift the administration attributes in part to tougher enforcement against illegal immigration and reduced pressure on housing demand.

Wages, the White House says, are rising alongside easing prices. Private-sector workers are on track to see real wages increase by about $1,300 in President Trump’s first full year back in office, clawing back purchasing power lost during the inflation surge of the previous administration. Gains are strongest among blue-collar workers, with annualized real earnings up roughly $1,800 for construction workers and $1,600 for manufacturing employees. Administration officials also took aim at critics who warned Trump’s tariff policies would reignite inflation, arguing the data shows no demonstrable inflationary impact despite repeated predictions from Wall Street and academic economists.

NEC Director Kevin Hassett on the latest inflation report: "It was just an absolute blockbuster report… We looked at 61 forecasts, and this number came in better than every single one of them." 🔥 pic.twitter.com/rBJpkmjuNa

— Rapid Response 47 (@RapidResponse47) December 18, 2025

Even commentators across the media spectrum acknowledged the strength of the report. CNBC’s Steve Liesman called it “a very good number,” while CNN’s Matt Egan said it was “another step in the right direction.” Harvard economist Ken Rogoff described the reading as “a better number than anyone was expecting,” adding, “There’s no other way to spin it.” Bloomberg’s Chris Anstey noted the figure came in two-tenths below the lowest estimate in a survey of 62 economists, calling it “remarkable,” while The Washington Post’s Andrew Ackerman wrote that inflation “cooled unexpectedly,” easing pressure on household budgets.

For the White House, the message was blunt: the inflation era is over. Officials framed Thursday’s report as proof that Trump has followed through on his promise to defeat the cost-of-living crisis he inherited, laying what they called the groundwork for a strong year ahead. As the president told the nation this week, the administration insists the progress is real — and that, in his words, the best is yet to come.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoDanielle Smith slams Skate Canada for stopping events in Alberta over ban on men in women’s sports

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTOTAL AND COMPLETE BLOCKADE: Trump cuts off Venezuela’s oil lifeline

-

Crime2 days ago

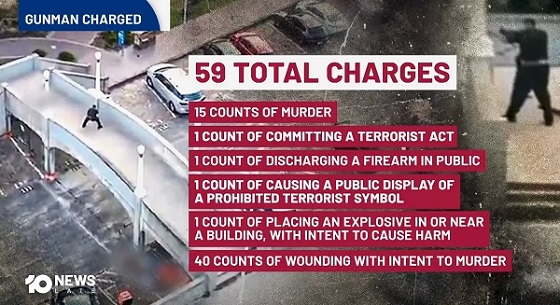

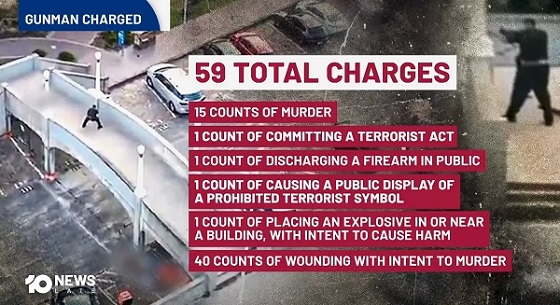

Crime2 days agoThe Uncomfortable Demographics of Islamist Bloodshed—and Why “Islamophobia” Deflection Increases the Threat

-

Daily Caller12 hours ago

Daily Caller12 hours ago‘Almost Sounds Made Up’: Jeffrey Epstein Was Bill Clinton Plus-One At Moroccan King’s Wedding, Per Report

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoSenator Demands Docs After ‘Blockbuster’ FDA Memo Links Child Deaths To COVID Vaccine

-

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours agoCanada Hits the Brakes on Population

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoChina Retaliates Against Missouri With $50 Billion Lawsuit In Escalating Covid Battle

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoBondi Beach Shows Why Self-Defense Is a Vital Right