Bjorn Lomborg

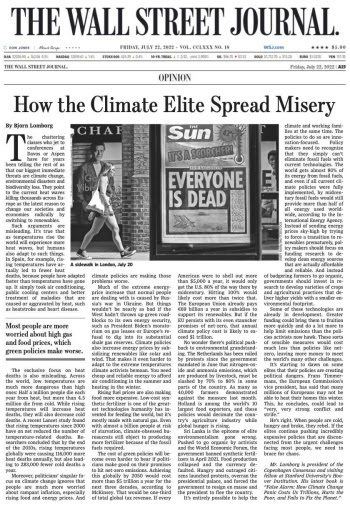

How the climate elite spread misery

Submitted by Bjorn Lomborg of the Copenhagen Consensus Center

|

The chattering classes who jet to conferences at Davos or Aspen have for years been telling the rest of us that our biggest immediate threats are climate change, environmental disasters and biodiversity loss. Yet, their singular focus on climate change ignores that people are much more worried about rampant inflation, especially rising food and energy prices.

Unfortunately, climate policies are making those problems worse. Lomborg writes in The Wall Street Journal that when people are cold, hungry and broke, they rebel. If the elites continue pushing incredibly expensive policies that are disconnected from the urgent challenges facing most people, we need to brace for chaos.

He also discussed this topic in interviews with Paul Gigot on The Journal Editorial Report, with Laura Ingrahamand with Stuart Varney.

The rich are denying the poor the power to develop

Rich countries – despite their climate rhetoric – are heavily relying on coal, oil and gas to cope with the current energy crisis. Yet, the G7 recently decided to stop funding any fossil fuel projects in the developing world, immorally blocking the path for poorer countries to develop. This is clearly not what developing countries want, as their leaders and ordinary citizens have made very clear.

Cost-benefit analysis can help policymakers maximize social returns

The Copenhagen Consensus approach has successfully introduced a rational, data-driven input to national priority-setting in many countries, including Bangladesh, Haiti, India, Ghana and Malawi in recent years.

With the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals reaching their halfway mark by the end of this year, it is time to assess how much progress countries have made towards the goals, and what they should focus on over the following eight years to create the largest-possible benefits for their societies.

Lomborg argues in a full page article for the leading Honduran newspaper El Heraldo that data from economic science can help politicians and their officials pick more of the really effective programs and slightly fewer of the less so, to maximize social returns for every dollar spent.

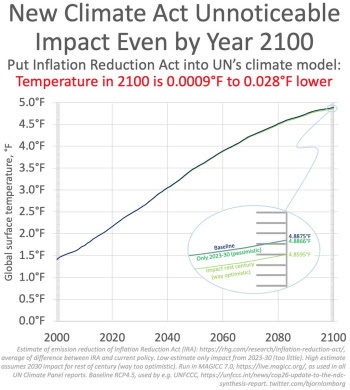

US $369 billion climate bill has virtually no impact

President Biden enthusiastically describes his administration’s new Inflation Reduction Act as “the most significant legislation in history to tackle the climate crisis.” Curiously though, neither officials nor media praising the IRA are stating the actual climate impact of spending $369 billion on the bill’s climate provisions.

There’s a good reason for this: As Lomborg explains on social media and TV interviews, e.g. with Varney and Kudlow, the UN’s own climate model shows that the impact will be impossible to detect by mid-century and still unnoticeable even in the best case by the year 2100.

Lomborg’s findings were also highlighted in a Wall Street Journal editorial and by Fox News which reported that the White House and leading proponents of the bill “didn’t respond to inquiries” pointing out that the bill would slow down rising temperatures by merely 0.0009°F to 0.028°F in 2100.

Green energy needs to be affordable for everyone

The climate-policy approach of trying to push consumers and businesses away from fossil fuels with price spikes is causing substantial pain with little climate pay-off. In rich countries, this approach risks growing resentment and strife, as France saw with the “yellow vest” protest movement.

But for the poorest billions, rising energy prices are even more serious because they block the pathway out of poverty and make fertilizer unaffordable for farmers, imperiling food production. The well-off in rich countries might be able to withstand the pain of some climate policies, but emerging economies like India or low-income countries in Africa cannot afford to sacrifice poverty eradication and economic development to tackle climate change.

Read Bjorn Lomborg’s globally-syndicated column in publications such as New York Post and Press of Atlantic City (both USA), Financial Post (Canada), Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Switzerland), O Globo (Brazil), The Australian, Berlingske (Denmark), de Telegraaf (Netherlands), Tempi(Italy), Listy z naszego sadu (Poland), Addis Fortune(Ethiopia), Milenio (Mexico), El Periodico (Guatemala), La Prensa (Nicaragua), La Tercera (Chile), El Pais(Uruguay), La Prensa Grafica (El Salvador), El Universal(Venezuela), CRHoy (Costa Rica) and Listy z naszego sadu(Poland).

Lomborg also discussed the importance of affordable and reliable energy on Tucker Carlson Tonight.

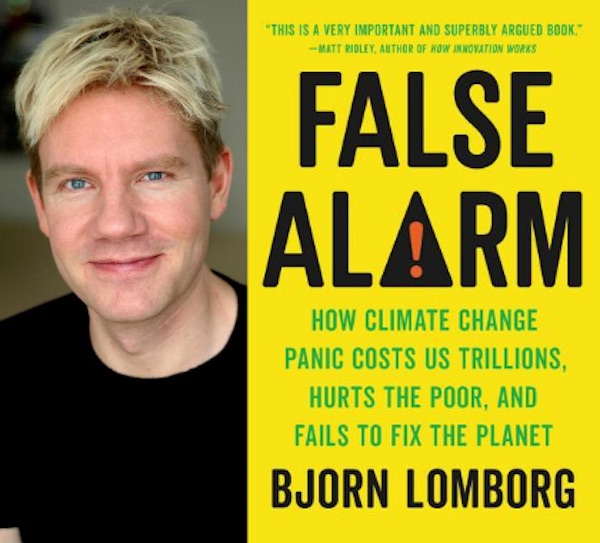

‘False Alarm’ around the world

Bjorn Lomborg’s bestselling book False Alarm* is now available in more than a dozen languages. Here is the Chinese edition, other translations include German, Czech, Spanish, Finnish, Norwegian and many more.

Bjorn Lomborg’s bestselling book False Alarm* is now available in more than a dozen languages. Here is the Chinese edition, other translations include German, Czech, Spanish, Finnish, Norwegian and many more.

The book remains an international success. The English original has been reprinted eight times in hardcover and six times in paperback, and several translations are also being reprinted now.

*As an Amazon Associate Copenhagen Consensus earns fromqualifying purchases.

Automotive

Electric cars just another poor climate policy

From the Fraser Institute

The electric car is widely seen as a symbol of a simple, clean solution to climate change. In reality, it’s inefficient, reliant on massive subsidies, and leaves behind a trail of pollution and death that is seldom acknowledged.

We are constantly reminded by climate activists and politicians that electric cars are cleaner, cheaper, and better. Canada and many other countries have promised to prohibit the sale of new gas and diesel cars within a decade. But if electric cars are really so good, why would we need to ban the alternatives?

And why has Canada needed to subsidize each electric car with a minimum $5,000 from the federal government and more from provincial governments to get them bought? Many people are not sold on the idea of an electric car because they worry about having to plan out where and when to recharge. They don’t want to wait for an uncomfortable amount of time while recharging; they don’t want to pay significantly more for the electric car and then see its used-car value decline much faster. For people not privileged to own their own house, recharging is a real challenge. Surveys show that only 15 per cent of Canadians and 11 per cent of Americans want to buy an electric car.

The main environmental selling point of an electric car is that it doesn’t pollute. It is true that its engine doesn’t produce any CO₂ while driving, but it still emits carbon in other ways. Manufacturing the car generates emissions—especially producing the battery which requires a large amount of energy, mostly achieved with coal in China. So even when an electric car is being recharged with clean power in BC, over its lifetime it will emit about one-third of an equivalent gasoline car. When recharged in Alberta, it will emit almost three-quarters.

In some parts of the world, like India, so much of the power comes from coal that electric cars end up emitting more CO₂ than gasoline cars. Across the world, on average, the International Energy Agency estimates that an electric car using the global average mix of power sources over its lifetime will emit nearly half as much CO₂ as a gasoline-driven car, saving about 22 tonnes of CO₂.

But using an electric car to cut emissions is incredibly ineffective. On America’s longest-established carbon trading system, you could buy 22 tonnes of carbon emission cuts for about $660 (US$460). Yet, Ottawa is subsidizing every electric car to the tune of $5,000 or nearly ten times as much, which increases even more if provincial subsidies are included. And since about half of those electrical vehicles would have been bought anyway, it is likely that Canada has spent nearly twenty-times too much cutting CO₂ with electric cars than it could have. To put it differently, Canada could have cut twenty-times more CO₂ for the same amount of money.

Moreover, all these estimates assume that electric cars are driven as far as gasoline cars. They are not. In the US, nine-in-ten households with an electric car actually have one, two or more non-electric cars, with most including an SUV, truck or minivan. Moreover, the electric car is usually driven less than half as much as the other vehicles, which means the CO₂ emission reduction is much smaller. Subsidized electric cars are typically a ‘second’ car for rich people to show off their environmental credentials.

Electric cars are also 320–440 kilograms heavier than equivalent gasoline cars because of their enormous batteries. This means they will wear down roads faster, and cost societies more. They will also cause more air pollution by shredding more particulates from tire and road wear along with their brakes. Now, gasoline cars also pollute through combustion, but electric cars in total pollute more, both from tire and road wear and from forcing more power stations online, often the most polluting ones. The latest meta-study shows that overall electric cars are worse on particulate air pollution. Another study found that in two-thirds of US states, electric cars cause more of the most dangerous particulate air pollution than gasoline-powered cars.

These heavy electric cars are also more dangerous when involved in accidents, because heavy cars more often kill the other party. A study in Nature shows that in total, heavier electric cars will cause so many more deaths that the toll could outweigh the total climate benefits from reduced CO₂ emissions.

Many pundits suggest electric car sales will dominate gasoline cars within a few decades, but the reality is starkly different. A 2023-estimate from the Biden Administration shows that even in 2050, more than two-thirds of all cars globally will still be powered by gas or diesel.

Source: US Energy Information Administration, reference scenario, October 2023

Fossil fuel cars, vast majority is gasoline, also some diesel, all light duty vehicles, the remaining % is mostly LPG.

Electric vehicles will only take over when innovation has made them better and cheaper for real. For now, electric cars run not mostly on electricity but on bad policy and subsidies, costing hundreds of billions of dollars, blocking consumers from choosing the cars they want, and achieving virtually nothing for climate change.

Bjorn Lomborg

Climate change isn’t causing hunger

From the Fraser Institute

Surprisingly, a green, low-carbon world produces less and more expensive food, and makes over 50 million more people hungry by mid-century.

Food scarcity affects many people around the world. Canada can help, as the world’s fifth largest exporter of agricultural goods and the fourth largest exporter of wheat. Indeed, Canada exports so much food that measured in calories it can feed more than 180 million people.

We hear often that carbon cuts are a priority because climate change is causing world hunger and that even Canada will be hit by higher prices and less choice. These alarmist claims are far from true, and the recommended policies are counterproductive.

Over the past century, hunger has dramatically declined. In 1928, the League of Nations estimated that more than two-thirds of humanity lived in a constant state of hunger. By 1970, malnutrition afflicted just one-quarter of all people. Since 2008, the world has seen less than one-in-ten of all people go hungry, although Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have increased the percentage from a low of just over 7 per cent to 9 per cent in 2023.

This positive trend is because humanity has become much better at producing food, and incomes have risen dramatically. For instance, we have more than quintupled cereal production since 1926, and more than halved global food prices. At the same time, extreme poverty has dropped precipitously, allowing parents to afford to buy their children more and better food.

There is obviously still more to do, but securing food for the vast majority of the world has been an unmitigated success in the human development story.

As we move towards 2050, it is likely incomes will keep increasing, with extreme poverty almost disappearing. At the same time, food prices will likely slightly decline or stay about the same, as even more people switch to higher-quality and more expensive foods. All credible predictions foresee even lower levels of malnutrition by mid-century.

The impact of climate change on food supply is often portrayed as terrible, but in reality, it means that things will get much better slightly slower. It will change conditions for most farmers, making conditions better for some and worse for others. In total, it is likely the net outcome will be worse, but only slightly so. One peer-reviewed estimate shows the climate impact on agriculture is equivalent to reducing global GDP by the end of the century by less than 0.06 per cent.

CO₂ is a plant fertilizer, as is well-known by enterprising tomato producers, who routinely pump CO₂ into their greenhouses to boost productivity. We see a similar impact across the living world. Since the 1970s, the increasing CO₂ concentration has caused the planet to become greener, producing more biomass. Satellites show that since 2000, the world has gotten so many more green leaves that their total area is larger than the entire area of Australia.

In total, models show that without climate change, the global amount of food, measured in calories, produced in 2050 will likely increase 51 per cent from 2010. Even under extreme, unrealistic climate change, it will increase 49 per cent. Across all models and scenarios, the difference in calories per person is one-tenth of a percent.

The graph shows how many children died each year from malnutrition from 1990 to 2021, with the World Health Organization estimating the impact of climate change up to 2050. Since 1990, the average number of children dying has declined dramatically from 6.5 million to 2.5 million each year. This is an incredible success story.

The WHO expects the decline to continue, with annual deaths halving once again. But in a world with climate change, deaths will still decline but slightly more slowly. Unfortunately, the lower death decline in 2050 created almost all the media headlines from the WHO study, entirely ignoring the dramatic reduction in overall death.

The overarching response from climate campaigners is to demand radical emission cuts to help. But this ignores two important facts. First, trying to affect change through climate policy is the slowest, costliest and least impactful way to help. While even significant climate policy will take over half a century to have any measurable impact and cost hundreds of trillions, it will at best help increase available calories by less than one-tenth of a percentage point. Instead, a focus on increased economic growth is over one hundred times more effective, increasing calorie availability by over 10 per cent. Moreover, it would work in years instead of centuries, and deliver a host of other, obvious benefits.

Second, cutting emissions increases most agricultural costs, like pushing up prices for fertilizer and gas for tractors, along with increased competition for land for biofuels and reforestation. Uselessly, most models just ignore these costs — like the WHO simply imagining a world without climate change. But it turns out that the impact of cutting emissions harms food production much more than climate change does. Surprisingly, a green, low-carbon world produces less and more expensive food, and makes over 50 million more people hungry by mid-century.

While we are being told stories of climate agricultural catastrophes and urged to cut emissions dramatically, the evidence shows that the impact is tiny, making the world improve slightly less fast. The proposed cure is worse than the problem it seeks to fix.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMORE OF THE SAME: Mark Carney Admits He Will Not Repeal the Liberal’s Bill C-69 – The ‘No Pipelines’ Bill

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days ago‘Coordinated and Alarming’: Allegations of Chinese Voter Suppression in 2021 Race That Flipped Toronto Riding to Liberals and Paul Chiang

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day ago‘I’m Cautiously Optimistic’: Doug Ford Strongly Recommends Canada ‘Not To Retaliate’ Against Trump’s Tariffs

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCalifornia planning to double film tax credits amid industry decline

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoEnergy sector will fuel Alberta economy and Canada’s exports for many years to come

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada may escape the worst as Trump declares America’s economic independence with Liberation Day tariffs

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoBig win for Alberta and Canada: Statement from Premier Smith

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoDon’t let the Liberals fool you on electric cars