Entertainment

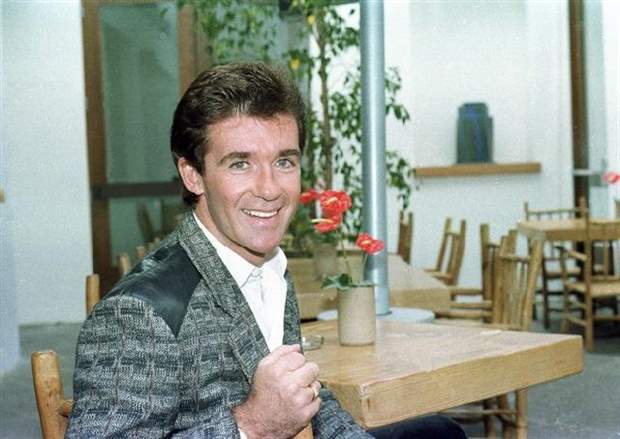

Growing Pains Star and TV Host Alan Thicke Dies at 69

Dec 13 23:21 – CP_PB – The Canadian Press

Alan Thicke, a versatile performer who gained his greatest renown

as the beloved dad on a long-running sitcom, has died at age 69.

Carleen Donovan, who is a publicist for Thicke’s son, singer

Robin Thicke, said the actor died from a heart attack on Tuesday in

Los Angeles. She had no further details.

Thicke was a Canadian-born TV host, writer, composer and actor

well-known in his homeland before making his name in the United

States, most notably with the ABC series “Growing Pains.”

On that comedy, which aired from 1985 to 1992, Thicke played Dr.

Jason Seaver, a psychiatrist and father-knows-best who moved his

practice into his home so his wife could go back to work as a

reporter. Along with his clients, he had three (later four) kids

under foot, including his oldest son, Mike, played by breakout

heart-throb Kirk Cameron, who served as a constant source of comedic

trouble for the family.

Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1947, Thicke was nominated for three

Emmy Awards for his work in the late 1970s as a writer for Barry

Manilow’s talk show, and later for a satirical take on the genre in

the variety show “America 2-Night.”

He composed several popular theme songs, including the original

theme for “The Wheel of Fortune” and other shows including “The

Facts of Life” and “Diff’rent Strokes.”

Perhaps his boldest assault on the U.S. market was as a virtual

unknown taking on the King of Late Night, Johnny Carson. “Thicke of

the Night” was a syndicated talk-music-and-comedy show meant to go

head-to-head against NBC’s “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny

Carson.”

It premiered in September 1983 with great fanfare, boasting an

innovative format and regulars including Richard Belzer, Arsenio

Hall, Gilbert Gottfried and Fred Willard. But all too quickly, it

was evident that Carson wasn’t going to be dethroned, and the

ambitious “Thicke” disappeared into the night after one season.

In the 1990s and beyond, Thicke stayed busy as a celebrity TV

host and with guest shots on dozens of series, including “How I Met

Your Mother” and, this year, the Netflix series “Fuller House”

and the NBC drama “This Is Us.”

Celebrities who had crossed paths with Thicke, whether through

music, acting or simply as friends, expressed their sorrow at news

of his death.

“I grew up watching him and got to know him through Robin. He

was always so kind to me,” John Legend posted on Twitter.

“You were a part of my family and hockey family. You will be

greatly missed. My heart hurts,” Candace Cameron Bure tweeted.

“RIP dear friend and gentleman,” posted Marlee Matlin.

Thicke’s fellow Canadians also responded quickly.

William Shatner tweeted that he was saddened by his friend’s

loss, and singer Anne Murray’s Twitter post said she was “shocked

and devastated,” recalling him as a friend as well as a writer and

producer of many of her TV specials.

The Edmonton Oilers also weighed in.

“RIP to one of the great ones, Alan Thicke,” was posted on the

hockey team’s website, with a photo of a young Thicke and Wayne

Gretzky on the ice.

Like any good Canadian, Thicke was a hockey fan, frequently

attending LA Kings games. He took credit for introducing the sport

to celebrity friends.

He began playing at age 5, but acknowledged he wasn’t very good

at it.

“You were expected to play,” he said in 1998. “I was never

good enough for the big time, but I always had fun at it.”

In 2003, Thicke received 30 stitches and lost five teeth after he

was struck by a puck while practicing for a celebrity fundraising

hockey game. “I won’t be playing any leading men roles in the next

couple of months,” he joked after the accident.

He had the satisfaction of seeing his musical skills passed down

to son Robin, a successful singer-songwriter and producer who, with

brother Brennan, was born to Thicke and the first of his three

wives, Gloria Loring.

In an email, Loring described Thicke’s passing as “a shock. We

were all just together for Thanksgiving. He was funny, talented and

deeply devoted to his family.”

Thicke also leaves a son, Carter, from his marriage to second

wife Gina Tolleson. He had been married to Tanya Callau since 2005.

___

AP Entertainment Writer Anthony McCartney in Los Angeles and AP

Music Writer Mefin Fekadu in New York contributed to this report.

_____

AP Entertainment Writer Anthony McCartney in Los Angeles and AP

Music Writer Mefin Fekadu in New York contributed to this report.

Business

Will Paramount turn the tide of legacy media and entertainment?

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

The recent leadership changes at Paramount Skydance suggest that the company may finally be ready to correct course after years of ideological drift, cultural activism posing as programming, and a pattern of self-inflicted financial and reputational damage.

Nowhere was this problem more visible than at CBS News, which for years operated as one of the most partisan and combative news organizations. Let’s be honest, CBS was the worst of an already left biased industry that stopped at nothing to censor conservatives. The network seemed committed to the idea that its viewers needed to be guided, corrected, or morally shaped by its editorial decisions.

This culminated in the CBS and 60 Minutes segment with Kamala Harris that was so heavily manipulated and so structurally misleading that it triggered widespread backlash and ultimately forced Paramount to settle a $16 million dispute with Donald Trump. That was not merely a legal or contractual problem. It was an institutional failure that demonstrated the degree to which political advocacy had overtaken journalistic integrity.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

For many longtime viewers across the political spectrum, that episode represented a clear breaking point. It became impossible to argue that CBS News was simply leaning left. It was operating with a mission orientation that prioritized shaping narratives rather than reporting truth. As a result, trust collapsed. Many of us who once had long-term professional, commercial, or intellectual ties to Paramount and CBS walked away.

David Ellison’s acquisition of Paramount marks the most consequential change to the studio’s identity in a generation. Ellison is not anchored to the old Hollywood ecosystem where cultural signaling and activist messaging were considered more important than story, audience appeal, or shareholder value.

His professional history in film and strategic business management suggests an approach grounded in commercial performance, audience trust, and brand rebuilding rather than ideological identity. That shift matters because Paramount has spent years creating content and news coverage that seemed designed to provoke or instruct viewers rather than entertain or inform them. It was an approach that drained goodwill, eroded market share, and drove entire segments of the viewing public elsewhere.

The appointment of Bari Weiss as the new chief editor of CBS News is so significant. Weiss has built her reputation on rejecting ideological conformity imposed from either side. She has consistently spoken out against antisemitism and the moral disorientation that emerges when institutions prioritize political messaging over honesty.

Her brand centers on the belief that journalism should clarify rather than obscure. During President Trump’s recent 60 Minutes interview, he praised Weiss as a “great person” and credited her with helping restore integrity and editorial seriousness inside CBS. That moment signaled something important. Paramount is no longer simply rearranging executives. It is rethinking identity.

The appointment of Makan Delrahim as Chief Legal Officer was an early indicator. Delrahim’s background at the Department of Justice, where he led antitrust enforcement, signals seriousness about governance, compliance, and restoring institutional discipline.

But the deeper and more meaningful shift is occurring at the ownership and editorial levels, where the most politically charged parts of Paramount’s portfolio may finally be shedding the habits that alienated millions of viewers.The transformation will not be immediate. Institutions develop habits, internal cultures, and incentive structures that resist correction. There will be internal opposition, particularly from staff and producers who benefited from the ideological culture that defined CBS News in recent years.

There will be critics in Hollywood who see any shift toward balance as a threat to their influence. And there will be outside voices who will insist that any move away from their preferred political posture is regression.

But genuine reform never begins with instant consensus. It begins with leadership willing to be clear about the mission.

Paramount has the opportunity to reclaim what once made it extraordinary. Not as a symbol. Not as a message distribution vehicle. But as a studio that understands that good storytelling and credible reporting are not partisan aims. They are universal aims. Entertainment succeeds when it connects with audiences rather than instructing them. Journalism succeeds when it pursues truth rather than victory.

In an era when audiences have more viewing choices than at any time in history, trust is an economic asset. Viewers are sophisticated. They recognize when they are being lectured rather than engaged. They know when editorial goals are political rather than informational. And they are willing to reward any institution that treats them with respect.

There is now reason to believe Paramount understands this. The leadership is changing. The tone is changing. The incentives are being reassessed.

It is not the final outcome. But it is a real beginning. As the great Winston Churchill once said; “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning”.

For the first time in a long time, the door to cultural realignment in legacy media is open. And Paramount is standing at the threshold and has the capability to become a market leader once again. If Paramount acts, the industry will follow.

Bill Flaig and Tom Carter are the Co-Founders of The American Conservatives Values ETF, Ticker Symbol ACVF traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Ticker Symbol ACVF

Learn more at www.InvestConservative.com

Censorship Industrial Complex

The FCC Should Let Jimmy Kimmel Be

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Energy21 hours ago

Energy21 hours agoThe U.S. Just Removed a Dictator and Canada is Collateral Damage

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump Says U.S. Strike Captured Nicolás Maduro and Wife Cilia Flores; Bondi Says Couple Possessed Machine Guns

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoVacant Somali Daycares In Viral Videos Are Also Linked To $300 Million ‘Feeding Our Future’ Fraud

-

International21 hours ago

International21 hours agoUS Justice Department Accusing Maduro’s Inner Circle of a Narco-State Conspiracy

-

Daily Caller9 hours ago

Daily Caller9 hours agoScathing Indictment Claims Nicolás Maduro Orchestrated Drug-Fueled ‘Culture Of Corruption’ Which Plagued Entire Region

-

International1 day ago

International1 day ago“Captured and flown out”: Trump announces dramatic capture of Maduro

-

Haultain Research19 hours ago

Haultain Research19 hours agoTrying to Defend Maduro’s Legitimacy

-

Daily Caller9 hours ago

Daily Caller9 hours agoTrump Says US Going To Run Venezuela After Nabbing Maduro