Alberta

Focus on tangible policies—not political finger-pointing— to reduce fire risks

From the Fraser Institute

Was the very specific area around Jasper—not the entire forested lands of Alberta—managed aggressively enough?

With the picturesque town of Jasper badly damaged by fire, Albertans and Canadians across the country are wondering how such destruction was allowed to happen.

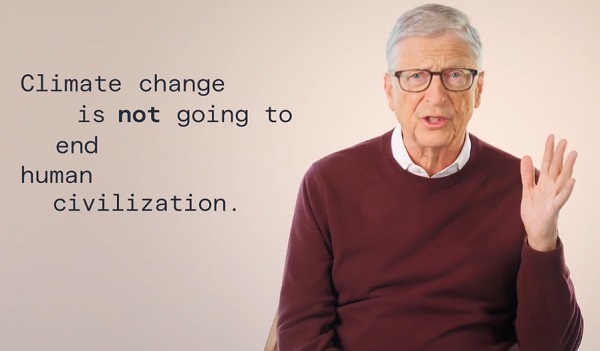

Much of the public debate assumes that the disaster, in some way, was human-caused or aggravated by governmental negligence or incompetence. Some argue that government policies to suppress natural wildfires, which were widely implemented across North America after the Second World War, allowed the build-up of massive amounts of fuel for potential mega-blazes. Others argue that governments have been negligent by failing to allow aggressive logging of dead trees and by using insufficient controlled burns to manage fuel loads of underbrush. Some, of course, blame climate change—specifically human-caused climate change. And yes, the climate has changed, warming about 1.2 degrees Celsius since 1850, which may contribute to a heightened risk of forest fires (although there’s no ability to attribute any single climatic event to climate change).

But focusing on these issues misses the forest for the trees and raises philosophical questions about humanity’s relationship with nature, specifically, whether or not it’s desirable—much less feasible—for humanity to think we can control nature at large scales and turn the world into a giant tame botanical garden. Further, focusing on these questions of “too much” or “too little” intervention mostly serves political interests trying to beat each other over the head about climate policies, which are at best capable of only slightly—very slightly—affecting the risk of future forest fires.

Rather, having studied environmental, health and safety policy for several decades, I believe we should focus on very different specific questions about how the fire was allowed to ravage Jasper. These questions cut through the foggier questions of how we manage nature and instead focus on how we manage human risks.

So, was the very specific area around Jasper—not the entire forested lands of Alberta—managed aggressively enough? In 2018, 350 hectares of trees around Jasper were removed. Apparently, that was not enough to protect the human-built environment. Parks Canada will have to answer that question in time.

Did the provincial and federal governments fall short in maintaining sufficient fire-fighting capabilities to protect Jasper? According to some reports, this was a significant source of failure, where the federal government, which maintains no ability to fight fires at night, failed to coordinate with Alberta’s provincial government, which does have night-fighting capabilities.

Did the town of Jasper take enough precautions to protect itself from the risk of conflagration? Are building codes in Jasper sufficiently stringent at fire-proofing human structures? Is the fuel burden within the township itself sufficiently controlled? More broadly, how much are we willing to spend to reduce risks? And how far should we aim to reduce those risks?

The answers to these questions could help produce tangible policies that may help reduce the risk of fire damage in the future.

There’s a lot of finger-pointing right now. Political point-scoring is the order of the day, particularly in the realm of climate policies. But using the Jasper fire for political ends distracts from the important questions about whether or not anybody or any level of government should try to tame nature outside of human-built environments. And about what policies will work best to protect towns like Jasper.

Author:

Alberta

Alberta government’s plan will improve access to MRIs and CT scans

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail and Tegan Hill

The Smith government may soon allow Albertans to privately purchase diagnostic screening and testing services, prompting familiar cries from defenders of the status quo. But in reality, this change, which the government plans to propose in the legislature in the coming months, would simply give Albertans an option already available to patients in every other developed country with universal health care.

It’s important for Albertans and indeed all Canadians to understand the unique nature of our health-care system. In every one of the 30 other developed countries with universal health care, patients are free to seek care on their own terms with their own resources when the universal system is unwilling or unable to satisfy their needs. Whether to access care with shorter wait times and a more rapid return to full health, to access more personalized services or meet a personal health need, or to access new advances in medical technology. But not in Canada.

That prohibition has not served Albertans well. Despite being one of the highest-spending provinces in one of the most expensive universal health-care systems in the developed world, Albertans endure some of the longest wait times for health care and some of the worst availability of advanced diagnostic and medical technologies including MRI machines and CT scanners.

Introducing new medical technologies is a costly endeavour, which requires money and the actual equipment, but also the proficiency, knowledge and expertise to use it properly. By allowing Albertans to privately purchase diagnostic screening and testing services, the Smith government would encourage private providers to make these technologies available and develop the requisite knowledge.

Obviously, these new providers would improve access to these services for all Alberta patients—first for those willing to pay for them, and then for patients in the public system. In other words, adding providers to the health-care system expands the supply of these services, which will reduce wait times for everyone, not just those using private clinics. And relief can’t come soon enough. In Alberta, in 2024 the median wait time for a CT scan was 12 weeks and 24 weeks for an MRI.

Greater access and shorter wait times will also benefit Albertans concerned about their future health or preventative care. When these Albertans can quickly access a private provider, their appointments may lead to the early discovery of medical problems. Early detection can improve health outcomes and reduce the amount of public health-care resources these Albertans may ultimately use in the future. And that means more resources available for all other patients, to the benefit of all Albertans including those unable to access the private option.

Opponents of this approach argue that it’s a move towards two-tier health care, which will drain resources from the public system, or that this is “American-style” health care. But these arguments ignore that private alternatives benefit all patients in universal health-care systems in the rest of the developed world. For example, Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia all have higher-performing universal systems that provide more timely care because of—not despite—the private options available to patients.

In reality, the Smith government’s plan to allow Albertans to privately purchase diagnostic screening and testing services is a small step in the right direction to reduce wait times and improve health-care access in the province. In fact, the proposal doesn’t go far enough—the government should allow Albertans to purchase physician appointments and surgeries privately, too. Hopefully the Smith government continues to reform the province’s health-care system, despite ill-informed objections, with all patients in mind.

Alberta

Canada’s heavy oil finds new fans as global demand rises

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Will Gibson

“The refining industry wants heavy oil. We are actually in a shortage of heavy oil globally right now, and you can see that in the prices”

Once priced at a steep discount to its lighter, sweeter counterparts, Canadian oil has earned growing admiration—and market share—among new customers in Asia.

Canada’s oil exports are primarily “heavy” oil from the Alberta oil sands, compared to oil from more conventional “light” plays like the Permian Basin in the U.S.

One way to think of it is that heavy oil is thick and does not flow easily, while light oil is thin and flows freely, like fudge compared to apple juice.

“The refining industry wants heavy oil. We are actually in a shortage of heavy oil globally right now, and you can see that in the prices,” said Susan Bell, senior vice-president of downstream research with Rystad Energy.

A narrowing price gap

Alberta’s heavy oil producers generally receive a lower price than light oil producers, partly a result of different crude quality but mainly because of the cost of transportation, according to S&P Global.

The “differential” between Western Canadian Select (WCS) and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) blew out to nearly US$50 per barrel in 2018 because of pipeline bottlenecks, forcing Alberta to step in and cut production.

So far this year, the differential has narrowed to as little as US$10 per barrel, averaging around US$12, according to GLJ Petroleum Consultants.

“The differential between WCS and WTI is the narrowest I’ve seen in three decades working in the industry,” Bell said.

Trans Mountain Expansion opens the door to Asia

Oil tanker docked at the Westridge Marine Terminal in Burnaby, B.C. Photo courtesy Trans Mountain Corporation

The price boost is thanks to the Trans Mountain expansion, which opened a new gateway to Asia in May 2024 by nearly tripling the pipeline’s capacity.

This helps fill the supply void left by other major regions that export heavy oil – Venezuela and Mexico – where production is declining or unsteady.

Canadian oil exports outside the United States reached a record 525,000 barrels per day in July 2025, the latest month of data available from the Canada Energy Regulator.

China leads Asian buyers since the expansion went into service, along with Japan, Brunei and Singapore, Bloomberg reports.

Asian refineries see opportunity in heavy oil

“What we are seeing now is a lot of refineries in the Asian market have been exposed long enough to WCS and now are comfortable with taking on regular shipments,” Bell said.

Kevin Birn, chief analyst for Canadian oil markets at S&P Global, said rising demand for heavier crude in Asia comes from refineries expanding capacity to process it and capture more value from lower-cost feedstocks.

“They’ve invested in capital improvements on the front end to convert heavier oils into more valuable refined products,” said Birn, who also heads S&P’s Center of Emissions Excellence.

Refiners in the U.S. Gulf Coast and Midwest made similar investments over the past 40 years to capitalize on supply from Latin America and the oil sands, he said.

While oil sands output has grown, supplies from Latin America have declined.

Mexico’s state oil company, Pemex, reports it produced roughly 1.6 million barrels per day in the second quarter of 2025, a steep drop from 2.3 million in 2015 and 2.6 million in 2010.

Meanwhile, Venezuela’s oil production, which was nearly 2.9 million barrels per day in 2010, was just 965,000 barrels per day this September, according to OPEC.

The case for more Canadian pipelines

Worker at an oil sands SAGD processing facility in northern Alberta. Photo courtesy Strathcona Resources

“The growth in heavy demand, and decline of other sources of heavy supply has contributed to a tighter market for heavy oil and narrower spreads,” Birn said.

Even the International Energy Agency, known for its bearish projections of future oil demand, sees rising global use of extra-heavy oil through 2050.

The chief impediments to Canada building new pipelines to meet the demand are political rather than market-based, said both Bell and Birn.

“There is absolutely a business case for a second pipeline to tidewater,” Bell said.

“The challenge is other hurdles limiting the growth in the industry, including legislation such as the tanker ban or the oil and gas emissions cap.”

A strategic choice for Canada

Because Alberta’s oil sands will continue a steady, reliable and low-cost supply of heavy oil into the future, Birn said policymakers and Canadians have options.

“Canada needs to ask itself whether to continue to expand pipeline capacity south to the United States or to access global markets itself, which would bring more competition for its products.”

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoUS Eating Canada’s Lunch While Liberals Stall – Trump Admin Announces Record-Shattering Energy Report

-

espionage14 hours ago

espionage14 hours agoU.S. Charges Three More Chinese Scholars in Wuhan Bio-Smuggling Case, Citing Pattern of Foreign Exploitation in American Research Labs

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoHow the UK and Canada Are Leading the West’s Descent into Digital Authoritarianism

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoU.S. Supreme Court frosty on Trump’s tariff power as world watches

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoEby should put up, shut up, or pay up

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCapital Flight Signals No Confidence In Carney’s Agenda

-

Justice1 day ago

Justice1 day agoCarney government lets Supreme Court decision stand despite outrage over child porn ruling

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoThe capital of capitalism elects a socialist mayor