Business

Federal government’s redistribution economics doesn’t work

From the Fraser Institute

By Jason Clemens, Jake Fuss, and Milagros Palacios

Prime Minister Trudeau’s vision for a more prosperous Canada relies on a much larger role for the federal government, with more spending, regulation, borrowing and higher taxes. By moving existing money around—both from higher-income workers to average Canadians and from the future to the present through borrowing—he believes the Canadian economy will be stronger and living standards will rise. But after nine years of governing, the evidence is clear—the prime minister’s redistribution economics doesn’t work and has actually reduced living standards in Canada.

Let’s first understand the magnitude of the changes made by the Trudeau government. Federal spending (excluding interest costs on debt) has risen from $256.2 billion in the last year of the Harper government to an estimated $483.6 billion this year, an increase of 88.7 per cent.

Even excluding COVID-related spending, the Trudeau government has recorded the five highest years of federal spending (on a per-person basis, after adjusting for inflation) in the history of the country, far surpassing spending during both world wars and the Great Recession.

Under Trudeau, the federal government has introduced several new programs (including dental care, daycare and pharmacare), and expanded several existing programs such as the cash transfer to families with children under 18 and corporate welfare.

Redistributing existing income has been a clear policy goal of the Trudeau government. From 2015 to 2022, average government transfers to families with children have increased from $12,685 to $15,750 (inflation-adjusted), an increase of 24.2 per cent. Yet among these same families, employment income only increased 8.0 per cent during the same period, meaning government transfers grew more than three times faster than their employment income. And as a share of household income, government transfers have increased from an average of 8.0 per cent between 1995 and 2007, when employment income was growing much faster, to 10.3 per cent in 2022.

The Trudeau government has financed this explosion in federal spending by borrowing, which is simply taxation deferred to the future, and tax increases.

Specifically, the government increased personal income taxes on professionals, entrepreneurs and successful business owners. It also increased taxes on businesses, which is an indirect and less transparent way of increasing taxes on average people since businesses don’t actually pay taxes, only people pay taxes. Higher business taxes mean less investment and thus lower wage growth for workers, lower payments to the business owners, and/or higher prices for consumers buying goods and services.

The Trudeau government also opaquely increased taxes on average Canadians. While it lowered the second personal income tax rate, it simultaneously eliminated several tax credits. As a result, 86 per cent of middle-income families experienced an increase in their personal income taxes as did 75 per cent of families with children in the bottom 20 per cent of income-earners.

But again, the government financed much of its new spending by borrowing, which means future tax increases. Consider that total federal debt stood at a little over $1.0 trillion when the Trudeau government took office in late-2015. By the government’s own estimates, total federal debt will reach almost $2.1 trillion next year.

Higher debt means higher interest costs, which divert money away from programs such as health care or badly needed tax relief. From 2015-16 (when Trudeau was first elected) to this year, federal debt interest costs have increased from $21.8 billion to an expected $54.1 billion. For context, this year the federal government expects to raise $54.1 billion from the GST, which means that every cent raised from the national sales tax will go to pay interest costs on the federal debt.

By focusing on moving around existing income (i.e. redistribution) rather than promoting income growth through investment and entrepreneurship, the Trudeau government has helped produce an outright economic growth crisis. Canada’s current decline in per-person GDP, a broad measure of living standards, is one of the longest and deepest declines of the last 40 years. Moreover, as of the end of 2023, the latest year of available data, the decline in living standards had not stopped so there’s a chance this could be the worst fall in living standards since at least the early-1980s.

According to a 2023 study, growth in per-person GDP from 2013 to 2022 was at its lowest rate since the Great Depression. Indeed, Canada’s post-COVID recovery was the 5th-weakest in the industrialized world. And prospects for the future are no better. A recent study by the OECD estimated that Canada would have the slowest growth in living standards among 32 high-income countries for the foreseeable future.

Simply put, the Trudeau government’s policies, which focused on government-led prosperity and moving income around instead of growing incomes, have led to a decline in living standards and economic malaise. Canadians are struggling when we should be leading the world in growth and prosperity. The only way to reverse our economic decline is to embrace a markedly different approach to policy focused on economic growth through entrepreneurship, investment and innovation.

Authors:

Business

Hudson’s Bay Bid Raises Red Flags Over Foreign Influence

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

A billionaire’s retail ambition might also serve Beijing’s global influence strategy. Canada must look beyond the storefront

When B.C. billionaire Weihong Liu publicly declared interest in acquiring Hudson’s Bay stores, it wasn’t just a retail story—it was a signal flare in an era where foreign investment increasingly doubles as geopolitical strategy.

The Hudson’s Bay Company, founded in 1670, remains an enduring symbol of Canadian heritage. While its commercial relevance has waned in recent years, its brand is deeply etched into the national identity. That’s precisely why any potential acquisition, particularly by an investor with strong ties to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), deserves thoughtful, measured scrutiny.

Liu, a prominent figure in Vancouver’s Chinese-Canadian business community, announced her interest in acquiring several Hudson’s Bay stores on Chinese social media platform Xiaohongshu (RedNote), expressing a desire to “make the Bay great again.” Though revitalizing a Canadian retail icon may seem commendable, the timing and context of this bid suggest a broader strategic positioning—one that aligns with the People’s Republic of China’s increasingly nuanced approach to economic diplomacy, especially in countries like Canada that sit at the crossroads of American and Chinese spheres of influence.

This fits a familiar pattern. In recent years, we’ve seen examples of Chinese corporate involvement in Canadian cultural and commercial institutions, such as Huawei’s past sponsorship of Hockey Night in Canada. Even as national security concerns were raised by allies and intelligence agencies, Huawei’s logo remained a visible presence during one of the country’s most cherished broadcasts. These engagements, though often framed as commercially justified, serve another purpose: to normalize Chinese brand and state-linked presence within the fabric of Canadian identity and daily life.

What we may be witnessing is part of a broader PRC strategy to deepen economic and cultural ties with Canada at a time when U.S.-China relations remain strained. As American tariffs on Canadian goods—particularly in aluminum, lumber and dairy—have tested cross-border loyalties, Beijing has positioned itself as an alternative economic partner. Investments into cultural and heritage-linked assets like Hudson’s Bay could be seen as a symbolic extension of this effort to draw Canada further into its orbit of influence, subtly decoupling the country from the gravitational pull of its traditional allies.

From my perspective, as a professional with experience in threat finance, economic subversion and political leveraging, this does not necessarily imply nefarious intent in each case. However, it does demand a conscious awareness of how soft power is exercised through commercial influence, particularly by state-aligned actors. As I continue my research in international business law, I see how investment vehicles, trade deals and brand acquisitions can function as instruments of foreign policy—tools for shaping narratives, building alliances and shifting influence over time.

Canada must neither overreact nor overlook these developments. Open markets and cultural exchange are vital to our prosperity and pluralism. But so too is the responsibility to preserve our sovereignty—not only in the physical sense, but in the cultural and institutional dimensions that shape our national identity.

Strategic investment review processes, cultural asset protections and greater transparency around foreign corporate ownership can help strike this balance. We should be cautious not to allow historically Canadian institutions to become conduits, however unintentionally, for geopolitical leverage.

In a world where power is increasingly exercised through influence rather than force, safeguarding our heritage means understanding who is buying—and why.

Scott McGregor is the managing partner and CEO of Close Hold Intelligence Consulting.

Bjorn Lomborg

Net zero’s cost-benefit ratio is crazy high

From the Fraser Institute

The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Canada has made a legal commitment to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. Back in 2015, then-Prime Minister Trudeau promised that climate action will “create jobs and economic growth” and the federal government insists it will create a “strong economy.” The truth is that the net zero policy generates vast costs and very little benefit—and Canada would be better off changing direction.

Achieving net zero carbon emissions is far more daunting than politicians have ever admitted. Canada is nowhere near on track. Annual Canadian CO₂ emissions have increased 20 per cent since 1990. In the time that Trudeau was prime minister, fossil fuel energy supply actually increased over 11 per cent. Similarly, the share of fossil fuels in Canada’s total energy supply (not just electricity) increased from 75 per cent in 2015 to 77 per cent in 2023.

Over the same period, the switch from coal to gas, and a tiny 0.4 percentage point increase in the energy from solar and wind, has reduced annual CO₂ emissions by less than three per cent. On that trend, getting to zero won’t take 25 years as the Liberal government promised, but more than 160 years. One study shows that the government’s current plan which won’t even reach net-zero will cost Canada a quarter of a million jobs, seven per cent lower GDP and wages on average $8,000 lower.

Globally, achieving net-zero will be even harder. Remember, Canada makes up about 1.5 per cent of global CO₂ emissions, and while Canada is already rich with plenty of energy, the world’s poor want much more energy.

In order to achieve global net-zero by 2050, by 2030 we would already need to achieve the equivalent of removing the combined emissions of China and the United States — every year. This is in the realm of science fiction.

The painful Covid lockdowns of 2020 only reduced global emissions by about six per cent. To achieve net zero, the UN points out that we would need to have doubled those reductions in 2021, tripled them in 2022, quadrupled them in 2023, and so on. This year they would need to be sextupled, and by 2030 increased 11-fold. So far, the world hasn’t even managed to start reducing global carbon emissions, which last year hit a new record.

Data from both the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration give added cause for skepticism. Both organizations foresee the world getting more energy from renewables: an increase from today’s 16 per cent to between one-quarter to one-third of all primary energy by 2050. But that is far from a transition. On an optimistically linear trend, this means we’re a century or two away from achieving 100 percent renewables.

Politicians like to blithely suggest the shift away from fossil fuels isn’t unprecedented, because in the past we transitioned from wood to coal, from coal to oil, and from oil to gas. The truth is, humanity hasn’t made a real energy transition even once. Coal didn’t replace wood but mostly added to global energy, just like oil and gas have added further additional energy. As in the past, solar and wind are now mostly adding to our global energy output, rather than replacing fossil fuels.

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that even after two centuries, humanity’s transition away from wood is not over. More than two billion mostly poor people still depend on wood for cooking and heating, and it still provides about 5 per cent of global energy.

Like Canada, the world remains fossil fuel-based, as it delivers more than four-fifths of energy. Over the last half century, our dependence has declined only slightly from 87 per cent to 82 per cent, but in absolute terms we have increased our fossil fuel use by more than 150 per cent. On the trajectory since 1971, we will reach zero fossil fuel use some nine centuries from now, and even the fastest period of recent decline from 2014 would see us taking over three centuries.

Global warming will create more problems than benefits, so achieving net-zero would see real benefits. Over the century, the average person would experience benefits worth $700 (CAD) each year.

But net zero policies will be much more expensive. The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Every year over the 21st century, costs would vastly outweigh benefits, and global costs would exceed benefits by over CAD 32 trillion each year.

We would see much higher transport costs, higher electricity costs, higher heating and cooling costs and — as businesses would also have to pay for all this — drastic increases in the price of food and all other necessities. Just one example: net-zero targets would likely increase gas costs some two-to-four times even by 2030, costing consumers up to $US52.6 trillion. All that makes it a policy that just doesn’t make sense—for Canada and for the world.

-

2025 Federal Election14 hours ago

2025 Federal Election14 hours agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

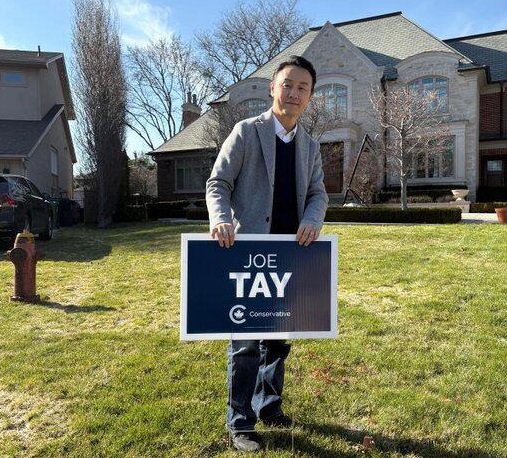

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoCHINESE ELECTION THREAT WARNING: Conservative Candidate Joe Tay Paused Public Campaign

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

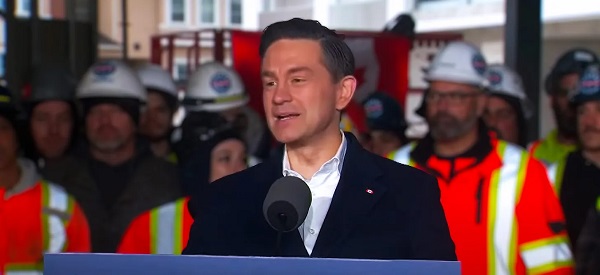

2025 Federal Election1 day agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCarney’s budget means more debt than Trudeau’s

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPope Francis has died aged 88

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust