Business

ESG doctrine and why it should not be adopted in professional organizations

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Graham Lane | Ian Madsen

The following introductory comments by Ian Madsen, Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Centre for Public Policy provide background on Graham Lane whose attached letter to CPA Manitoba strongly criticizes that organization’s embrace of ESG.

Graham Lane is a retired CA and has had a multifaceted professional career spanning almost 50 years in the public and private sectors of seven provinces as a Senior Executive and Consultant.

In the public sector, before concluding his career as the Chairman of the Manitoba Public Utility Board (PUB), he consulted for three provincial governments and was employed by four provinces. In Manitoba, he was the CEO of Credit Union Central, bringing in online banking, a Vice-President of Public Investments of Manitoba, the interim President of Manitoba Public Insurance (MPI), reorganizing the corporation after its massive losses of 1986, a Vice-President of the University of Winnipeg, and the CEO of the Workers Compensation Board, restructuring the insurer and returning it to solvency. His experience with Crown Corporations goes well beyond Manitoba, he was the Comptroller of Saskatchewan’s Crown Investments Corporation, and a consultant reviewing government auto insurance in BC and workers compensation in Nova Scotia. He received the gold medal in Philosophy as an undergraduate, and a Paul Harris Fellowship from Rotary International for excellence in vocational service. Throughout his career, and wherever he worked, consulted or volunteered, he maintained an external objectivity. In recent years the Frontier Centre for Public Policy has been honoured by his presence of the Centre’s Expert Advisory Panel where he has been able to share his extensive public and private sector operations knowledge.

Environmental, Social and Governance Standards, so-called ‘ESG’, and scoring arose from ‘Responsible Investing’ efforts in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Institutional and other investors sought to influence corporations that were seen to be involved in, first, the Vietnam War, and, later on, in conducting business in Apartheid-era South Africa. Since then, the movement has morphed, now evolved into ESG.

ESG is essentially a covert way of exerting control over public companies by means other than buying control in the stock market. It is a ‘so-called’ ‘Social Justice’ movement. It seeks to impose non-market ideology on publicly traded companies, such as ‘Green Energy’ and ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’, or, ‘DEI’. The latter two are the main goals of the effort, and are divisive and destructive. There are three paths that this crusade takes: regulatory, professional, and institutional.

The regulatory one is to compel governments to require that ESG standards be applied. This can occur through regulatory agencies such as the Ontario Securities Commission, the most powerful such body in Canada, or through its sister regulatory bodies in other provinces and territories. Federal and provincial legislation can also be passed and implemented to force some or all ESG-related strictures upon corporations.

This institutional path exerts influence upon the largest investors in Canada: public pension plans, such as the Canada Pension Plan and its CPP Investment Board, Quebec’s Caisse de depot et placements, which does the same for enrolees in Quebec; the federal Public Service Pension Plan, Ontario Teachers; and other provincial and professional pension plan investment bodies. Many, if not all of them, to a greater or lesser extent, have already agreed to and endorse ESG ‘principles’, and now attempt to induce the companies they invest in to subscribe to those edicts.

The professional path is, perhaps, the most pernicious. ESG scoring and rating are akin to accounting and financial reporting and analysis, so the professional bodies responsible for those things, such as provincial and national accounting professionals associations, and national and international associations of financial analysts, such as the Chartered Financial Analysts Institute, have begun to adopt ESG regimens.

However, ESG scoring is not just harmful, it is wildly subjective and susceptible to inaccuracy. ESG evolved from Marxist notions of ‘equity’. It is aligned with collectivist, non-market ideology. Transferring much or most managerial decision-making to those with neither direct expertise nor responsibility for its consequences would be irresponsible, an attack on capitalism itself.

Informed and strong opposition, as in the following letter from 2023 by Graham Lane, to the President of the Manitoba office of the Chartered Professional Accounts, should be heeded if citizens, taxpayers, investors and society at large want to avoid the Canadian economy becoming dominated by and managed by ESG criteria. These diverge radically from traditional proven fiduciary and corporate stewardship standards and principles – in favour of ‘Social Justice’ approved outcomes – which potentially damage or destroy returns for pension plan members, and other indirect and direct investors and the economy as a whole.

Ian Madsen

Senior Policy Analyst

January 4, 2024

Text of letter begins below:

Graham Lane, CPA CA (retired)

xxx (address withheld)

Winnipeg, MB

Geeta Tucker, FCPA, FCMA

President and CEO

CPA Manitoba Office

1675 – One Lombard Place

Winnipeg, MB

R3B OX3

August 26, 2023

Re: ESG courses and accreditation, CPA – “A New Frontier: Sustainability and ESG for CPAs and business professionals” (CPA Canada Career and Professional Development)

Dear Ms. Geeta Tucker:

I recently read, with concern, that the association is offering ESG ‘training’, towards immersing members in validating the Environmental Social Governance – ESG’ -movement’. (“A New Frontier: Sustainability and ESG for CPAs and business professionals.”) I also note, with further concern, a supporting column published on the subject (July/August 2023 Pivot CPA magazine). Our profession and members should ‘think twice’ before ‘jumping in’.

“ESG” stands for environment, social and governance. ESG investors aim to buy the shares of companies that have demonstrated their willingness to improve their performance in these areas. ESG is an acronym that refers of environmental, social, and governance standards that socially conscious investors use to select investments. These criteria consider how well public companies safeguard the environment and the communities where it works, and how they ensure management and corporate governance met high standards. For many people, ESG investing is more than a three-acronym. It’s a practical, real-world process for addressing how a company serves all its stakeholders: workers, communities, customers, shareholders and the environment. ESG offers one strategy for aligning your investment with your values, it’s not the only approach.”

But, the ESG ‘movement’, originally driven by good intentions, has been co-opted by lobbyists, special interest groups, and various NGOs. Recent reviews have revealed ESG’s lackluster performance in creating meaningful environment change, and others have highlighted chronic abuse of flawed methodologies.

ESG has gradually suffused the business and finance world, from its origins in academia and the ‘activist’ movements of various ‘social justice’ interest groups. Now, through the actions of provincial and national CPA bodies, our profession is validating and endorsing the central tenets and precepts of ESG valuation, which is misguided and harmful. ESG is antithetical to the aims of the accounting profession, which is, in part, to give honest, objective and rigorous appraisal of the assets, liabilities, and the profit and cash generating capacity of firms. Risk factors and externalities, including environmental issues, are already covered by GAAP and IFRS standards in financial reporting.

While the proponents of ESG promote it as a means of providing a fuller perspective on important aspects of a firm’s place in society, its community, and the ecosystem, and of its handling of other ‘stakeholders’, who are neither shareholders nor managers of a firm, it does not. In fact, by dubiously evaluating those other aspects of a firm’s status, it badly serves investors by creating possibly devastating conflicts and contradictions. This could imperil a firm and its ability to act autonomously towards providing goods and services to the public, jobs to its employees, and dividends (or capital gains) to its owners (ultimately, the public).

The problem of ESG evaluation and its ‘scoring’ are well-known. There is a lack of consistent standards and objectivity, including those of quantitative metrics that are logical and germane. ESG’s principles are dedicated to diverting and subverting top management; i.e., by substituting other ‘stakeholder’ concerns or aims from those of the firm – which is, principally, to seek short-term and long-term profitability and viability, subject to the constraints of laws, regulations, and physical limitations.

It is important to recall that ESG’s origins were in social activism, with the ‘S’ linked to anti-Apartheid movements on university campus and shareholders’ meetings in the 1980’s and ‘90’s. Then the ‘S’ was ‘Responsible Investing’ – an attempt to isolate and boycott the then-racist regime in South Africa. Then, by bringing the-apartheid regime to the negotiating table, with representatives of the disenfranchised opposition, eventually, it brought to an end to Apartheid itself.

Efforts should continue to draw attention to ‘conflict diamonds’, and minerals being extracted by indentured children and adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, along with the continuing oppression of minority groups in regions of China. For these situations, and, other places around the world where there are violent or corrupt regimes, western companies should be careful as to their dealings. Yet, these problems are generally already noted as business risks in proper, professional, corporate reporting, and are also subject to the law and multilateral guidelines and sanctions.

The ‘Environmental’ component of ESG is, perhaps, the primary one that the anti-capitalist movement have been most preoccupied with. It, the movement, accepts entirely, and bases its ideology on, presumptions that are not, despite media rhetoric, accurate. It is not true that global temperatures that are unadjusted or otherwise manipulated by un-objective persons are rising.

Nor is rising temperatures are ‘entirely’ due to higher levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is not the most important factor in the direction, or magnitude, of any warming temperatures that might occur. Nor do any of some vaunted climate models predict (at least with any degree of certainty) what temperatures will be anywhere on the planet, let alone on average. Such efforts have repeatedly provided false projections.

Media and academic pundits have cited heat waves, or other events, as evidence of the tangible effects of purported warming, but these have been anecdotal and ignored other events, with contradictory evidence in other regions. Past predictions of ice cap and glacier melting, desertification, and more and stronger storms and other dire events, have yet come to naught.

Another fraught part of the ‘E’ in ESG scoring is determining ‘Scope 1, 2 and 3’ GHG emissions. The first one, ‘Scope 1’, is not ‘terribly difficult’ to do, but the other two Scopes 2 and 3, need to delve into what suppliers, customers and others do with the goods or services of the subject firm. These would be extremely difficult to determine let alone accurately quantify – and can be very expensive and/or unreliable to even attempt to calculate. At best, such tests might also give a distorted impression of an environmental impact – even ‘damage’ ’ that the firm may, or may not be, imparting.

Finally, the whole ‘Green Transition’ has become a rent-seeking lobby, attempting to capture government and its tax dollars. Their proponents’ supposition of touted ‘benefits’ of solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and batteries – drastically altering or decimating the conventional energy, transportation and agriculture industries – are often erroneous or fraudulent, ignoring the full costs, financial and environmental, of their proposals.

The ’G’, ‘Governance’, part of ESG is also elusive and amorphous. While some of it has to do with the accountability of upper management, that is already covered by the responsibility of the Compensation, Nomination and Succession committees of the Boards of Directors (of all but the smallest companies), and also by regulations and supervision of applicable provincial Securities Commissions. Any malfeasance by managers or other employees, or by governments or other overseas organizations, involving bribery or other crimes, is covered by laws already. Engagement with ‘less-than-perfect’ regimes overseas is unavoidable for some industries, and it is unlikely that any quantitative scoring of such interactions or presence would or could be validly determined.

Another aim of the ESG effort is to compel companies to commit to some form of DEI: ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion’.

In practice, DEI cannot merely be about outreach to historically disadvantaged or under-represented communities, but cqn lead to active discrimination against employees or potential hires who are not members of those communities. Commitment to hiring and promotion goals in those communities is legally questionable, but that is almost the least of the problems DEI entails. One of the worst is about the engagement of DEI directors, or outside DEI consultants, to conduct divisive and stressful DEI training, such as sensitivity and ‘microaggression’ awareness and role-playing exercises.

ESG scoring that rewards destructive efforts would or could make companies and organizations alter their operation to appear to ‘earn’ higher scores, while actually damaging their ability to foster a productive work environment, retain qualified staff, generate an adequate rate of return on invested capital, or survive as a going concern.

Another element of the ‘G’ in ESG is to try to inject parties other than shareholders or management into Governance, diluting shareholders’ control – which could or would obscure responsibility and accountability, and could badly delay or derail important capital allocation and other corporate decisions. These groups are suppliers, customers, those affected by the operations or products or services of the company, and communities in which the company operates, and potentially others. A covert attempt to subvert capitalism itself, and the market economy, might happen.

ESG advocates have engendered support by claiming that higher-ESG rated firms, and the shares in those firms, perform better than the ‘typical’ company. However, that is untrue. Studies of Canadian and American ESG and ‘Ethical’ funds (over the past five, ten, and even longer time periods) indicate that they underperform index funds; i.e., funds that invest in the entire market of large firms traded on a stock exchange.

Any funds that claim otherwise are consciously, or unconsciously investing in a style tilted to certain sectors; quite often the low-environmental impact IT sector. Such companies can perform well in a shorter time frame. When examining ESG funds, moreover, it often turns out that they invest in most of the same companies as the index funds – though perhaps with a higher management fee. Also, they could have peculiar criteria for higher ESG ratings, most glaringly rating some oil companies higher than other apparently ‘Green’ ones, such as Tesla. Elimination of low-ESG rated firms from investing can concentrate risk by narrowing diversification, thus violating a central, crucial tenet of investment risk management.

ESG has gained considerable support from corporate interests, including prominent institutional investors such as Blackrock (Chairman, Larry Fink) and public pension funds. While such ‘responsible investing’ may have a glowing aura, it can also have a pernicious effect of trying to coerce corporate management to attain public policy that ‘progressive’ politicians, academics, think tanks and other operatives believe are paramount. Those goals can supersede the shareholder returns that are vital to guarantee beneficiaries of pension funds and other institutional investment portfolios receive their promised benefits. This could violate the fiduciary duty of investment portfolio managers, which is to strive for the best risk-adjusted return that they can. (Several ‘green energy’ companies’ share prices have declined, some drastically in the past year.)

Several state governments in the United States have prohibited ESG-based investment.The Saskatchewan and Alberta provincial governments may also intercede if this ‘movement’ strikes at the vital energy industry.

Giving the considerable reputational power of CPAs, for the Association to ‘educate’ its members in a potentially destructive endeavour, such as ESG evaluation, is a mistake. It would be folly to add yet more risk and damage by validating and promoting ESG.

ESG advocates are now on the defensive, from information available recounted herein. Shouldn’t our profession review its decision to promote ESG?

Yours Sincerely,

Graham Lane, CPA CA (retired)

Former Chairman, Manitoba’s Public Utilities Board

c.c. Pamela Steer, CEO, President and CEO, CPA, Canada

Paul Ferris, Editor, Pivot, CPA Canada

Business

Canada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

From LifeSiteNews

Of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s fleet of 1,200 drones, 79% pose national security risks due to them being made in China

Canada’s top police force spent millions on now near-useless and compromised security drones, all because they were made in China, a nation firmly controlled by the Communist Chinese Party (CCP) government.

An internal report by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to Canada’s Senate national security committee revealed that $34 million in taxpayer money was spent on a fleet of 973 Chinese-made drones.

Replacement drones are more than twice the cost of the Chinese-made ones between $31,000 and $35,000 per unit. In total, the RCMP has about 1,228 drones, meaning that 79 percent of its drone fleet poses national security risks due to them being made in China.

The RCMP said that Chinese suppliers are “currently identified as high security risks primarily due to their country of origin, data handling practices, supply chain integrity and potential vulnerability.”

In 2023, the RCMP put out a directive that restricted the use of the made-in-China drones, putting them on duty for “non-sensitive operations” only, however, with added extra steps for “offline data storage and processing.”

The report noted that the “Drones identified as having a high security risk are prohibited from use in emergency response team activities involving sensitive tactics or protected locations, VIP protective policing operations, or border integrity operations or investigations conducted in collaboration with U.S. federal agencies.”

The RCMP earlier this year said it was increasing its use of drones for border security.

Senator Claude Carignan had questioned the RCMP about what kind of precautions it uses in contract procurement.

“Can you reassure us about how national security considerations are taken into account in procurement, especially since tens of billions of dollars have been announced for procurement?” he asked.

“I want to make sure national security considerations are taken into account.”

The use of the drones by Canada’s top police force is puzzling, considering it has previously raised awareness of Communist Chinese interference in Canada.

Indeed, as reported by LifeSiteNews, earlier in the year, an RCMP internal briefing note warned that agents of the CCP are targeting Canadian universities to intimidate them and, in some instances, challenge them on their “political positions.”

The final report from the Foreign Interference Commission concluded that operatives from China may have helped elect a handful of MPs in both the 2019 and 2021 Canadian federal elections. It also concluded that China was the primary foreign interference threat to Canada.

Chinese influence in Canadian politics is unsurprising for many, especially given former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s past admiration for China’s “basic dictatorship.”

As reported by LifeSiteNews, a Canadian senator appointed by Trudeau told Chinese officials directly that their nation is a “partner, not a rival.”

China has been accused of direct election meddling in Canada, as reported by LifeSiteNews.

As reported by LifeSiteNews, an exposé by investigative journalist Sam Cooper claims there is compelling evidence that Carney and Trudeau are strongly influenced by an “elite network” of foreign actors, including those with ties to China and the World Economic Forum. Despite Carney’s later claims that China poses a threat to Canada, he said in 2016 the Communist Chinese regime’s “perspective” on things is “one of its many strengths.”

Business

The EU Insists Its X Fine Isn’t About Censorship. Here’s Why It Is.

Europe calls it transparency, but it looks a lot like teaching the internet who’s allowed to speak.

|

When the European Commission fined X €120 million on December 5, officials could not have been clearer. This, they said, was not about censorship. It was just about “transparency.”

They repeat it so often you start to wonder why.

The fine marks the first major enforcement of the Digital Services Act, Europe’s new censorship-driven internet rulebook.

It was sold as a consumer protection measure, designed to make online platforms safer and more accountable, and included a whole list of censorship requirements, fining platforms that don’t comply.

The Commission charged X with three violations: the paid blue checkmark system, the lack of advertising data, and restricted data access for researchers.

None of these touches direct content censorship. But all of them shape visibility, credibility, and surveillance, just in more polite language.

Musk’s decision to turn blue checks into a subscription feature ended the old system where establishment figures, journalists, politicians, and legacy celebrities got verification.

The EU called Musk’s decision “deceptive design.” The old version, apparently, was honesty itself. Before, a blue badge meant you were important. After, it meant you paid. Brussels prefers the former, where approved institutions get algorithmic priority, and the rest of the population stays in the queue.

The new system threatened that hierarchy. Now, anyone could buy verification, diluting the aura of authority once reserved for anointed voices.

Reclaim The Net is sustained by its readers.

Your support fuels the fight for privacy, free speech and digital civil liberties while giving you access to exclusive content, practical how to guides, premium features and deeper dives into freedom-focused tech.

Become a supporter here.

However, that’s not the full story. Under the old Twitter system, verification was sold as a public service, but in reality it worked more like a back-room favor and a status purchase.

The main application process was shut down in 2010, so unless you were already famous, the only way to get a blue check was to spend enough money on advertising or to be important enough to trigger impersonation problems.

Ad Age reported that advertisers who spent at least fifteen thousand dollars over three months could get verified, and Twitter sales reps told clients the same thing. That meant verification was effectively a perk reserved for major media brands, public figures, and anyone willing to pay. It was a symbol of influence rationed through informal criteria and private deals, creating a hierarchy shaped by cronyism rather than transparency.

Under the new X rules, everyone is on a level playing field.

Government officials and agencies now sport gray badges, symbols of credibility that can’t be purchased. These are the state’s chosen voices, publicly marked as incorruptible. To the EU, that should be a safeguard.

The second and third violations show how “transparency” doubles as a surveillance mechanism. X was fined for limiting access to advertising data and for restricting researchers from scraping platform content. Regulators called that obstruction. Musk called it refusing to feed the censorship machine.

The EU’s preferred researchers aren’t neutral archivists. Many have been documented coordinating with governments, NGOs, and “fact-checking” networks that flagged political content for takedown during previous election cycles.

They call it “fighting disinformation.” Critics call it outsourcing censorship pressure to academics.

Under the DSA, these same groups now have the legal right to demand data from platforms like X to study “systemic risks,” a phrase broad enough to include whatever speech bureaucrats find undesirable this month.

The result is a permanent state of observation where every algorithmic change, viral post, or trending topic becomes a potential regulatory case.

The advertising issue completes the loop. Brussels says it wants ad libraries to be fully searchable so users can see who’s paying for what. It gives regulators and activists a live feed of messaging, ready for pressure campaigns.

The DSA doesn’t delete ads; it just makes it easier for someone else to demand they be deleted.

That’s how this form of censorship works: not through bans, but through endless exposure to scrutiny until platforms remove the risk voluntarily.

The Commission insists, again and again, that the fine has “nothing to do with content.”

That may be true on a direct level, but the rules shape content all the same. When governments decide who counts as authentic, who qualifies as a researcher, and how visibility gets distributed, speech control doesn’t need to be explicit. It’s baked into the system.

Brussels calls it user protection. Musk calls it punishment for disobedience. This particular DSA fine isn’t about what you can say, it’s about who’s allowed to be heard saying it.

TikTok escaped similar scrutiny by promising to comply. X didn’t, and that’s the difference. The EU prefers companies that surrender before the hearing. When they don’t, “transparency” becomes the pretext for a financial hammer.

The €120 million fine is small by tech standards, but symbolically it’s huge.

It tells every platform that “noncompliance” means questioning the structure of speech the EU has already defined as safe.

In the official language of Brussels, this is a regulation. But it’s managed discourse, control through design, moderation through paperwork, censorship through transparency.

And the louder they insist it isn’t, the clearer it becomes that it is.

|

|

|

|

Reclaim The Net Needs Your

With your help, we can do more than hold the line. We can push back. We can expose censorship, highlight surveillance overreach, and amplify the voices of those being silenced.

If you have found value in our work, please consider becoming a supporter.

Your support does more than keep us independent. It also gives you access to exclusive content, deep dive exploration of freedom focused technology, member-only features, and practical how-to posts that help you protect your rights in the real world.

You help us expand our reach, educate more people, and continue this fight.

Please become a supporter today.

Thank you for your support.

|

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoTrump Deals Biden’s EV Dreams A Death Blow

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoLoblaws Owes Canadians Up to $500 Million in “Secret” Bread Cash

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoCanada’s EV Mandate Is Running On Empty

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhy Does Canada “Lead” the World in Funding Racist Indoctrination?

-

Dan McTeague1 day ago

Dan McTeague1 day agoWill this deal actually build a pipeline in Canada?

-

Media1 day ago

Media1 day agoThey know they are lying, we know they are lying and they know we know but the lies continue

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoUS Condemns EU Censorship Pressure, Defends X

-

Focal Points19 hours ago

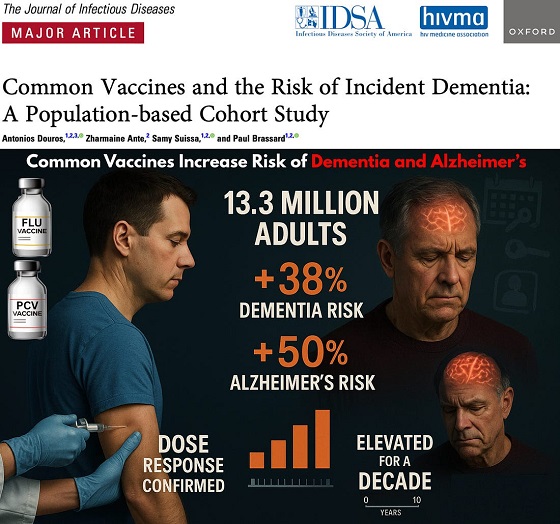

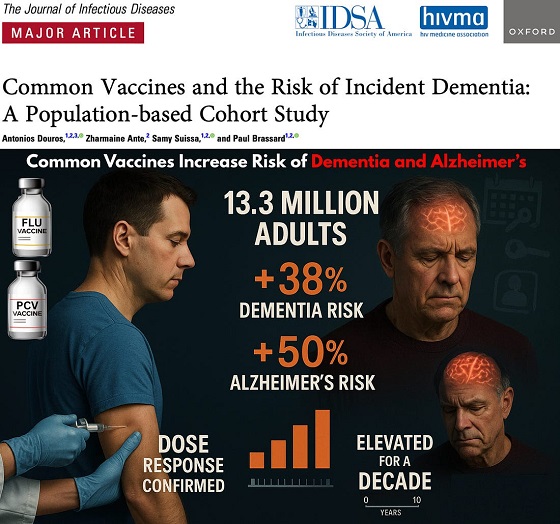

Focal Points19 hours agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s