Fraser Institute

Dearth of medical resources harms Canadian patients

From the Fraser Institute

The imbalance between high spending and poor access to doctors, hospital beds and vital imaging technology, coupled with untimely access to services, can, and does, have a detrimental impact on patients.

Whether it’s a lack of family physicians or other health-care workers, Canadians know we have a serious health-care labour shortage on our hands. The implications of this shortage aren’t lost on patients (including Ellie O’Brien) who’ve possibly faced delays in accessing organ transplants because potential donors need a regular family doctor to screen them to begin the transplant process.

Given these access issues, coupled with some of the longest recorded wait times for medical procedures on record, is it any wonder that Canadians are dissatisfied with how their provincial governments handle health care?

While one instinct might be to demand governments spend more on health care, it’s not clear we’re getting good value in return for what’s already being spent. In fact, compared to 29 other high-income countries with universal health care, Canada spent the most on health care as a share of the economy at 12.6 per cent in 2021, the latest year of available comparable data (after adjusting for differences in the age structure of each country’s population).

But what do we get in return for this spending?

As far as medical resources go, not a whole lot. In 2021, Canadians had some of the fewest medical resources in the developed world. Out of 30 high-income countries with universal health care, Canada ranked 28th on physician availability at 2.8 per 1,000 people, far behind countries such as seventh-ranked Switzerland (4.5 physicians per 1,000) and tenth-ranked Australia (at 4.3 physicians per 1,000).

But doctors are just one part of the puzzle. Canada also ranked low on available hospital beds (23rd of 29 countries), meaning patients often face delays for hospital care. It can also mean that patients end up being treated for their illness outside a traditional patient room—such as a hospital hallway, a phenomenon that has spread to many provinces.

We also see a low availability of other key medical resources including diagnostic equipment. In 2019, Canada ranked 25th of 29 comparable countries with universal health care on the number of MRIs (10.3 units per million people) compared to top-ranked Japan, which had four times as many MRIs as Canada. And we ranked 26th out of 30 countries on CT scanners (14.9 scanners per million people) compared to second-ranked Australia, which had five times as many CT scanners. It’s also worth noting that a large a portion of Canada’s diagnostic machines are remarkably old.

It’s no accident that countries such as Australia, which actually spend less of its economy on health care compared to Canada, perform better than Canada on measures of resource availability and timeliness of care. Unlike Canada, Australia embraces its private sector as an integral part of its universal health-care system. With 41 per cent of all hospital care in Australia occurring in private hospitals in 2021/22, private hospitals can act as a pressure valve for the entire system, particularly in times of crisis. Indeed, the country outperforms Canada on measures of timely access to family doctor appointments, specialist care and non-emergency surgery, and has done so regularly for years.

The imbalance between high spending and poor access to doctors, hospital beds and vital imaging technology, coupled with untimely access to services, can, and does, have a detrimental impact on patients. For some, this problem can be life threatening. Without genuine reform based on real world lessons from higher performing universal health-care countries including Australia, it’s impossible to reasonably expect our health-care system to improve despite its hefty price tag.

Author:

Alberta

CPP another example of Albertans’ outsized contribution to Canada

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Amid the economic uncertainty fuelled by Trump’s trade war, its perhaps more important than ever to understand Alberta’s crucial role in the federation and its outsized contribution to programs such as the Canada Pension Plan (CPP).

From 1981 to 2022, Albertan’s net contribution to the CPP—meaning the amount Albertans paid into the program over and above what retirees in Alberta received in CPP payments—was $53.6 billion. In 2022 (the latest year of available data), Albertans’ net contribution to the CPP was $3.0 billion.

During that same period (1981 to 2022), British Columbia was the only other province where residents paid more into the CPP than retirees received in benefits—and Alberta’s contribution was six times greater than B.C.’s contribution. Put differently, residents in seven out of the nine provinces that participate in the CPP (Quebec has its own plan) receive more back in benefits than they contribute to the program.

Albertans pay an outsized contribution to federal and national programs, including the CPP because of the province’s relatively high rates of employment, higher average incomes and younger population (i.e. more workers pay into the CPP and less retirees take from it).

Put simply, Albertan workers have been helping fund the retirement of Canadians from coast to coast for decades, and without Alberta, the CPP would look much different.

How different?

If Alberta withdrew from the CPP and established its own standalone provincial pension plan, Alberta workers would receive the same retirement benefits but at a lower cost (i.e. lower CPP contribution rate deducted from our paycheques) than other Canadians, while the contribution rate—essentially the CPP tax rate—to fund the program would likely need to increase for the rest of the country to maintain the same benefits.

And given current demographic projections, immigration patterns and Alberta’s long history of leading the provinces in economic growth, Albertan workers will likely continue to pay more into the CPP than Albertan retirees get back from it.

Therefore, considering Alberta’s crucial role in national programs, the next federal government—whoever that may be—should undo and prevent policies that negatively impact the province and Albertans ability to contribute to Canada. Think of Bill C-69 (which imposes complex, uncertain and onerous review requirements on major energy projects), Bill C-48 (which bans large oil tankers off B.C.’s northern coast and limits access to Asian markets), an arbitrary cap on oil and gas emissions, numerous other “net-zero” targets, and so on.

Canada faces serious economic challenges, including a trade war with the United States. In times like this, it’s important to remember Alberta’s crucial role in the federation and the outsized contributions of Alberta workers to the wellbeing of Canadians across the country.

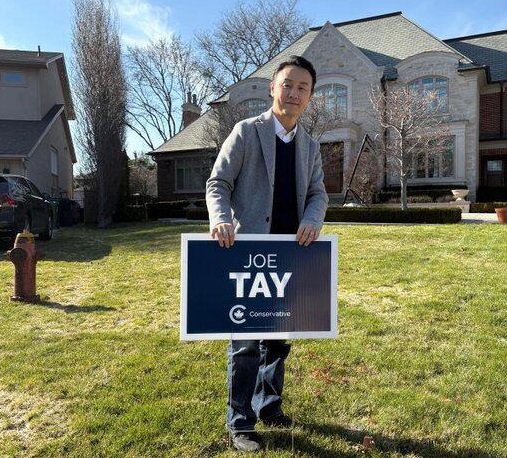

2025 Federal Election

Homebuilding in Canada stalls despite population explosion

From the Fraser Institute

By Austin Thompson and Steven Globerman

Between 1972 and 2019, Canada’s population increased by 1.8 residents for every new housing unit started compared to 3.9 new residents in 2024. In other words, Canada must now house more than twice as many new residents per new housing unit as it did during the five decades prior to the pandemic

In many parts of Canada, the housing affordability crisis continues with no end in sight. And many Canadians, priced out of the housing market or struggling to afford rent increases, are left wondering how much longer this will continue.

Simply put, too few housing units are being built for the country’s rapidly growing population, which has exploded due to record-high levels of immigration and the federal government’s residency policies.

As noted in a new study published by the Fraser Institute, the country added an all-time high 1.2 million new residents in 2023—more than double the previous record in 2019—and another 951,000 new residents in 2024. Altogether, Canada’s population has grown by about 3 million people since 2022—roughly matching the total population increase during the 1990s.

Meanwhile, homebuilding isn’t keeping up. In 2024, construction started on roughly 245,000 new housing units nationwide—down from a recent peak of 272,000 in 2021. By contrast, in the 1970s construction started on more than 240,000 housing units (on average) per year—when Canada’s population grew by approximately 280,000 people annually.

In fact, between 1972 and 2019, Canada’s population increased by 1.8 residents for every new housing unit started compared to 3.9 new residents in 2024. In other words, Canada must now house more than twice as many new residents per new housing unit as it did during the five decades prior to the pandemic. And of course, housing follows the laws of supply and demand—when a lot more prospective buyers and renters chase a limited supply of new homes, prices increase.

This key insight should guide the policy responses from all levels of government.

For example, the next federal government—whoever that may be—should avoid policies that merely fuel housing demand such as home savings accounts. And provincial governments (including in Ontario and British Columbia) should scrap any policies that discourage new housing supply such as rent controls, which reduce incentives to build rental housing. At the municipal level, governments across the country should ensure that permit approval timelines and building fees do not discourage builders from breaking ground. Increasing housing supply is, however, only part of the solution. The next federal government should craft immigration and residency policies so population growth doesn’t overwhelm available housing supply, driving up costs for Canadians.

It’s hard to predict how long Canada’s housing affordability crisis will last. But without more homebuilding, slower population growth, or both, there’s little reason to expect affordability woes to subside anytime soon.

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCarney’s Hidden Climate Finance Agenda

-

2025 Federal Election19 hours ago

2025 Federal Election19 hours agoTrump Has Driven Canadians Crazy. This Is How Crazy.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoFormer WEF insider accuses Mark Carney of using fear tactics to usher globalism into Canada

-

2025 Federal Election22 hours ago

2025 Federal Election22 hours agoThe Anhui Convergence: Chinese United Front Network Surfaces in Australian and Canadian Elections

-

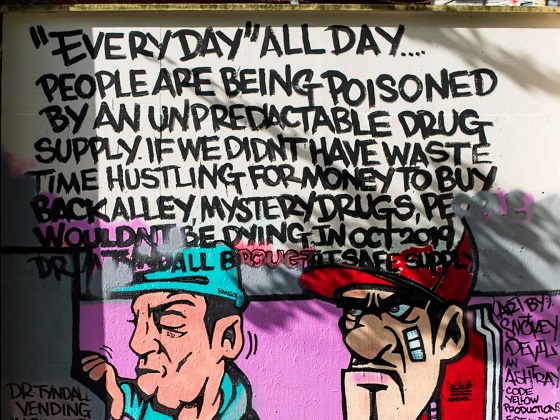

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoStudy links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

-

Automotive7 hours ago

Automotive7 hours agoHyundai moves SUV production to U.S.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoConservatives promise to ban firing of Canadian federal workers based on COVID jab status

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPope Francis Got Canadian History Wrong