Business

Cut corporate income taxes massively to increase growth, prosperity

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

Business groups are justifiably opposed to the federal government’s June 25 increase of the inclusion rate for capital gains tax. But there is another corporate income tax increase looming. It will come in the form of a 2018 corporate tax reduction that is set to expire starting this year. Ottawa ironically intended it to make Canada more competitive amid the 2018 tax reform and cut in the United States.

According to a study by Trevor Tombe at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, Canada’s corporate income tax rate on new investments will jump from 13.7 percent to 17 percent by 2027. Even worse, for Canada’s high-value-added manufacturing sector, taxation will triple. Higher corporate income taxes, in a nation experiencing difficulties in encouraging domestic or foreign investment in new plant equipment, will struggle to reverse meagre productivity growth—a problem noted by the Bank of Canada.

Heavier taxation will hinder future improvement in incomes and the standard of living, making it a serious issue. Increasing income tax on businesses and investment will not increase prosperity and personal income. The legislation to make the 2018 provisions permanent is, alarmingly, not urgent to politicians.

At least one policy could make Canada more attractive to business, investors, and hard-pressed ordinary citizens. It would be to slash corporate income taxes substantially. Another is to make paying taxes easier, as Magna Corporation founder Frank Stronach suggested. It may surprise some Canadians, but Ottawa’s take from corporate income taxes is a relatively small. However, it is a fast-rising proportion of federal overall revenue: 21 percent in fiscal 2022–23, according to the government, up from 13 percent in fiscal 2000–21, notes the OECD.

Letting companies pay taxes and reducing the tax burden on ordinary people might seem OK to some. However, what happens is that every corporate expense, including taxes, reduces cash flow that reaches individuals. The money remaining in the hands of businesses could either be reinvested or paid out as dividends to owners. Let’s remember that owners are founding families, pension fund beneficiaries (employees, citizens), and ordinary individuals.

As there are fewer available funds, there will be a reduced capacity for capital investment. Investment is required to replace existing equipment, or add new equipment, devices, software, and vehicles for businesses. It only keeps companies competitive and makes employees more productive. This, in turn, makes the whole economy more profitable, thereby increasing taxes paid to governments.

As for the questionable reason for the tax increase, aiming to generate more revenue, recent experience in the United States is informative. The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act reduced corporate income tax from 39 percent of pre-tax income to 21 percent. It resulted in U.S. federal corporate income tax revenue rising 25 percent from 2017 to 2021. Capital investment rose dramatically too, by 20 percent, a key goal of many Canadian policymakers.

Until recently, the Republic of Ireland had a corporate income tax rate of 12.5 percent, a key selling point in its successful efforts to attract foreign investment over the past several decades. Ireland, with few natural resources, is one of the richest and fastest-growing of the OECD nations, despite a bad real estate crash 15 years ago. Near the lowest in the OECD in tax burden, it nevertheless has a high quality of life and services.

If anything, Canada should cut corporate income taxes to below the levels of its main trading partners and rivals. To do so, it will have to extricate itself from the ill-conceived international treaty that compels signatory nations and territories to have a floor rate of at least 15 percent of pre-tax income. Ottawa seems enamoured of multinational agreements and organizations, so it may be highly reluctant to abrogate membership in this growth-dampening arrangement. The statutory federal corporate income tax rate in Canada is 15 percent, but all provincial governments impose their own levies on top of that, ranging from 8 percent in Alberta to 16 percent in Prince Edward Island.

By cutting taxes, we can pave the way for a brighter economic future, marked by increased productivity and the prosperity we all yearn for. This move will also ensure our international competitiveness, a goal we are currently struggling to achieve with our current 25 percent rate (OECD). Canada has a hard time attracting investors. Raising taxes will neither attract more of them nor encourage more investment from existing Canada-domiciled entrepreneurs and companies.

Ian Madsen is senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Alberta

Pierre Poilievre – Per Capita, Hardisty, Alberta Is the Most Important Little Town In Canada

From Pierre Poilievre

Business

Why it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

The Port of Prince Rupert on the north coast of British Columbia. Photo courtesy Prince Rupert Port Authority

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Will Gibson

Moratorium does little to improve marine safety while sending the wrong message to energy investors

In 2019, Martha Hall Findlay, then-CEO of the Canada West Foundation, penned a strongly worded op-ed in the Globe and Mail calling the federal ban of oil tankers on B.C.’s northern coast “un-Canadian.”

Six years later, her opinion hasn’t changed.

“It was bad legislation and the government should get rid of it,” said Hall Findlay, now director of the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

The moratorium, known as Bill C-48, banned vessels carrying more than 12,500 tonnes of oil from accessing northern B.C. ports.

Targeting products from one sector in one area does little to achieve the goal of overall improved marine transport safety, she said.

“There are risks associated with any kind of transportation with any goods, and not all of them are with oil tankers. All that singling out one part of one coast did was prevent more oil and gas from being produced that could be shipped off that coast,” she said.

Hall Findlay is a former Liberal MP who served as Suncor Energy’s chief sustainability officer before taking on her role at the University of Calgary.

She sees an opportunity to remove the tanker moratorium in light of changing attitudes about resource development across Canada and a new federal government that has publicly committed to delivering nation-building energy projects.

“There’s a greater recognition in large portions of the public across the country, not just Alberta and Saskatchewan, that Canada is too dependent on the United States as the only customer for our energy products,” she said.

“There are better alternatives to C-48, such as setting aside what are called Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas, which have been established in areas such as the Great Barrier Reef and the Galapagos Islands.”

The Business Council of British Columbia, which represents more than 200 companies, post-secondary institutions and industry associations, echoes Hall Findlay’s call for the tanker ban to be repealed.

“Comparable shipments face no such restrictions on the East Coast,” said Denise Mullen, the council’s director of environment, sustainability and Indigenous relations.

“This unfair treatment reinforces Canada’s over-reliance on the U.S. market, where Canadian oil is sold at a discount, by restricting access to Asia-Pacific markets.

“This results in billions in lost government revenues and reduced private investment at a time when our economy can least afford it.”

The ban on tanker traffic specifically in northern B.C. doesn’t make sense given Canada already has strong marine safety regulations in place, Mullen said.

Notably, completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion in 2024 also doubled marine spill response capacity on Canada’s West Coast. A $170 million investment added new equipment, personnel and response bases in the Salish Sea.

“The [C-48] moratorium adds little real protection while sending a damaging message to global investors,” she said.

“This undermines the confidence needed for long-term investment in critical trade-enabling infrastructure.”

Indigenous Resource Network executive director John Desjarlais senses there’s an openness to revisiting the issue for Indigenous communities.

“Sentiment has changed and evolved in the past six years,” he said.

“There are still concerns and trust that needs to be built. But there’s also a recognition that in addition to environmental impacts, [there are] consequences of not doing it in terms of an economic impact as well as the cascading socio-economic impacts.”

The ban effectively killed the proposed $16-billion Eagle Spirit project, an Indigenous-led pipeline that would have shipped oil from northern Alberta to a tidewater export terminal at Prince Rupert, B.C.

“When you have Indigenous participants who want to advance these projects, the moratorium needs to be revisited,” Desjarlais said.

He notes that in the six years since the tanker ban went into effect, there are growing partnerships between B.C. First Nations and the energy industry, including the Haisla Nation’s Cedar LNG project and the Nisga’a Nation’s Ksi Lisims LNG project.

This has deepened the trust that projects can mitigate risks while providing economic reconciliation and benefits to communities, Dejarlais said.

“Industry has come leaps and bounds in terms of working with First Nations,” he said.

“They are treating the rights of the communities they work with appropriately in terms of project risk and returns.”

Hall Findlay is cautiously optimistic that the tanker ban will be replaced by more appropriate legislation.

“I’m hoping that we see the revival of a federal government that brings pragmatism to governing the country,” she said.

“Repealing C-48 would be a sign of that happening.”

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Crime2 days ago

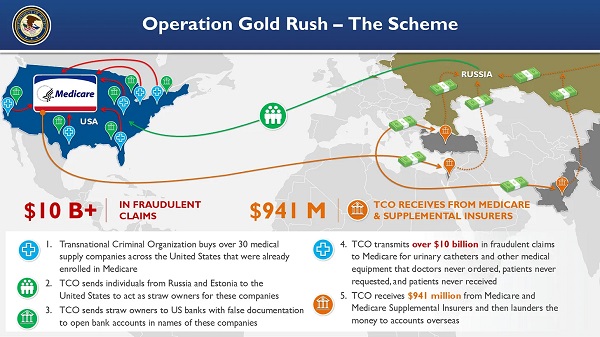

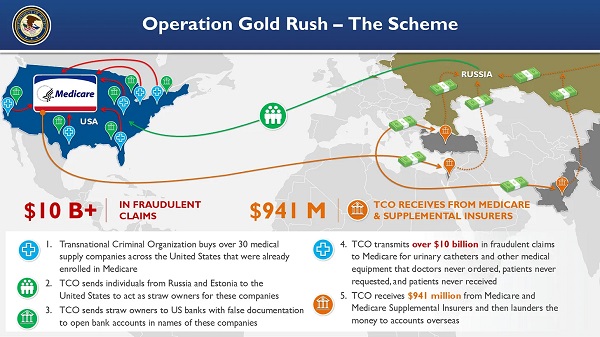

Crime2 days agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Business14 hours ago

Business14 hours agoWhy it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoGlobal media alliance colluded with foreign nations to crush free speech in America: House report

-

Alberta9 hours ago

Alberta9 hours agoAlberta Provincial Police – New chief of Independent Agency Police Service

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Alberta13 hours ago

Alberta13 hours agoPierre Poilievre – Per Capita, Hardisty, Alberta Is the Most Important Little Town In Canada

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoElon Musk slams Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill,’ calls for new political party