Fraser Institute

Cost of Ottawa’s gun ban fiasco may reach $6 billion

From the Fraser Institute

By Gary Mauser

According to the government, it has already spent $67.2 million, which includes compensation for 60 federal employees working on the “buyback,” which still doesn’t exist.

Four years ago, the Trudeau government banned “1,500 types” of “assault-style firearms.” It’s time to ask if public safety has improved as promised.

This ban instantly made it a crime for federally-licensed firearms owners to buy, sell, transport, import, export or use hundreds of thousands formerly legal rifles and shotguns. According to the government, the ban targets “assault-style weapons,” which are actually classic semi-automatic rifles and shotguns that have been popular with hunters and sport shooters for more than 100 years. When announcing the ban, the prime minister said the government would confiscate the banned firearms and their legal owners would be “grandfathered” or receive “fair compensation.” That hasn’t happened.

As of October 2024, the government has revealed no plans about how it will collect the newly-banned firearms nor has it made any provisions for compensation in any federal budget since the announcement in 2020. Originally, the government enacted a two-year amnesty period to allow compliance with the ban. This amnesty expired in April 2022 and has been twice extended, first to Oct. 30, 2023, then to Oct. 30, 2025.

Clearly, the ban—which the government calls a “buyback”—has been a gong show from the beginning. Since Trudeau’s announcement four years ago, virtually none of the banned firearms have been surrendered. The Ontario government refuses to divert police resources to cooperate with this federal “buyback” scheme. The RCMP’s labour union has said it’s a “misdirected effort when it comes to public safety.” The Canadian Sporting Arms & Ammunition Association, which represents firearms retailers, said it will have “zero involvement” in helping confiscate these firearms. Even Canada Post wants nothing to do with Trudeau’s “buyback” plan. And again, the government has revealed no plan for compensation—fair or otherwise.

And yet, according to the government, it has already spent $67.2 million, which includes compensation for 60 federal employees working on the “buyback,” which still doesn’t exist.

It remains unclear just how many firearms the 2020 ban includes. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates range between 150,000 to more than 500,000, with an estimated total value between $47 million and $756 million. These costs only include the value of the confiscated firearms and exclude the administrative costs to collect them and the costs of destroying the collected firearms. The total cost of this ban to taxpayers will be more than $4 billion and possibly more than $6 billion.

Nevertheless, while the ban of remains a confusing mess, after four years we should be able to answer one key question. Has the ban made Canadians safer?

According to Statistics Canada, firearm-related violent crime swelled by 10 per cent from 2020 to 2022 (the latest year of comparable data), from 12,614 incidents to 13,937 incidents. And in “2022, the rate of firearm-related violent crime was 36.7 incidents per 100,000 population, an 8.9% increase from 2021 (33.7 incidents per 100,000 population). This is the highest rate recorded since comparable data were first collected in 2009.”

Nor have firearm homicides decreased since 2020. Perhaps this is because lawfully-held firearms are not the problem. According to StatsCan, “the firearms used in homicides were rarely legal firearms used by their legal owners.” However, crimes committed by organized crime have increased by more than 170 per cent since 2016 (from 4,810 to 13,056 crimes).

Meanwhile, the banned firearms remain locked in the safes of their legal owners who have been vetted by the RCMP and are monitored nightly for any infractions that might endanger public safety.

Indeed, hunters and sport shooters are among the most law-abiding people in Canada. Many Canadian families and Indigenous peoples depend on hunting to provide food for the family dinner table through legal harvesting, with the added benefit of getting out in the wilderness and spending time with family and friends. In 2015, hunting and firearm businesses alone contributed more than $5.9 billion to Canada’s economy and supported more than 45,000 jobs. Hunters are the largest contributors to conservation efforts, contributing hundreds of millions of dollars to secure conservation lands and manage wildlife. The number of licensed firearms owners has increased 17 per cent since 2015 (from 2.026 million to 2.365 million) in 2023.

If policymakers in Ottawa and across the country want to reduce crime and increase public safety, they should enact policies that actually target criminals and use our scarce tax dollars wisely to achieve these goals.

Author:

Business

Residents in economically free states reap the rewards

From the Fraser Institute

A report published by the Fraser Institute reaffirms just how much more economically free some states are compared with others. These are places where citizens are allowed to make more of their economic choices. Their taxes are lighter, and their regulatory burdens are easier. The benefits for workers, consumers and businesses have been clear for a long time.

There’s another group of states to watch: “movers” that have become much freer in recent decades. These are states that may not be the freest, but they have been cutting taxes and red tape enough to make a big difference.

How do they fare?

I recently explored this question using 22 years of data from the same Economic Freedom of North America index. The index uses 10 variables encompassing government spending, taxation and labour regulation to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states.

Some states, such as New Hampshire, have long topped the list. It’s been in the top five for three decades. With little room to grow, the Granite State’s level of economic freedom hasn’t budged much lately. Others, such as Alaska, have significantly improved economic freedom over the last two decades. Because it started so low, it remains relatively unfree at 43rd out of 50.

Three states—North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho—have managed to markedly increase and rank highly on economic freedom.

In 2000, North Carolina was the 19th most economically free state in the union. Though its labour market was relatively unhindered by the state’s government, its top marginal income tax rate was America’s ninth-highest, and it spent more money than most states.

From 2013 to 2022, North Carolina reduced its top marginal income tax rate from 7.75 per cent to 4.99 per cent, reduced government employment and allowed the minimum wage to fall relative to per-capita income. By 2022, it had the second-freest labour market in the country and was ninth in overall economic freedom.

North Dakota took a similar path, reducing its 5.54 per cent top income tax rate to 2.9 per cent, scaling back government employment, and lowering its minimum wage to better reflect local incomes. It went from the 27th most economically free state in the union in 2000 to the 10th freest by 2022.

Idaho saw the most significant improvement. The Gem State has steadily improved spending, taxing and labour market freedom, allowing it to rise from the 28th most economically free state in 2000 to the eighth freest in 2022.

We can contrast these three states with a group that has achieved equal and opposite distinction: California, Delaware, New Jersey and Maryland have managed to decrease economic freedom and end up among the least free overall.

What was the result?

The economies of the three liberating states have enjoyed almost twice as much economic growth. Controlling for inflation, North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho grew an average of 41 per cent since 2010. The four repressors grew by just 24 per cent.

Among liberators, statewide personal income grew 47 per cent from 2010 to 2022. Among repressors, it grew just 26 per cent.

In fact, when it comes to income growth per person, increases in economic freedom seem to matter even more than a state’s overall, long-term level of freedom. Meanwhile, when it comes to population growth, placing highly over longer periods of time matters more.

The liberators are not unique. There’s now a large body of international evidence documenting the freedom-prosperity connection. At the state level, high and growing levels of economic freedom go hand-in-hand with higher levels of income, entrepreneurship, in-migration and income mobility. In economically free states, incomes tend to grow faster at the top and bottom of the income ladder.

These states suffer less poverty, homelessness and food insecurity and may even have marginally happier, more philanthropic and more tolerant populations.

In short, liberation works. Repression doesn’t.

Alberta

Alberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Last Friday, less than a week before Christmas, the Smith government quietly released the final report from its Alberta Next Panel, which assessed Alberta’s role in Canada. Among other things, the panel recommends that the federal government transfer some of its tax revenue to provincial governments so they can assume more control over the delivery of provincial services. Based on Canada’s experience in the 1990s, this plan could deliver real benefits for Albertans and all Canadians.

Federations such as Canada typically work best when governments stick to their constitutional lanes. Indeed, one of the benefits of being a federalist country is that different levels of government assume responsibility for programs they’re best suited to deliver. For example, it’s logical that the federal government handle national defence, while provincial governments are typically best positioned to understand and address the unique health-care and education needs of their citizens.

But there’s currently a mismatch between the share of taxes the provinces collect and the cost of delivering provincial responsibilities (e.g. health care, education, childcare, and social services). As such, Ottawa uses transfers—including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT)—to financially support the provinces in their areas of responsibility. But these funds come with conditions.

Consider health care. To receive CHT payments from Ottawa, provinces must abide by the Canada Health Act, which effectively prevents the provinces from experimenting with new ways of delivering and financing health care—including policies that are successful in other universal health-care countries. Given Canada’s health-care system is one of the developed world’s most expensive universal systems, yet Canadians face some of the longest wait times for physicians and worst access to medical technology (e.g. MRIs) and hospital beds, these restrictions limit badly needed innovation and hurt patients.

To give the provinces more flexibility, the Alberta Next Panel suggests the federal government shift tax points (and transfer GST) to the provinces to better align provincial revenues with provincial responsibilities while eliminating “strings” attached to such federal transfers. In other words, Ottawa would transfer a portion of its tax revenues from the federal income tax and federal sales tax to the provincial government so they have funds to experiment with what works best for their citizens, without conditions on how that money can be used.

According to the Alberta Next Panel poll, at least in Alberta, a majority of citizens support this type of provincial autonomy in delivering provincial programs—and again, it’s paid off before.

In the 1990s, amid a fiscal crisis (greater in scale, but not dissimilar to the one Ottawa faces today), the federal government reduced welfare and social assistance transfers to the provinces while simultaneously removing most of the “strings” attached to these dollars. These reforms allowed the provinces to introduce work incentives, for example, which would have previously triggered a reduction in federal transfers. The change to federal transfers sparked a wave of reforms as the provinces experimented with new ways to improve their welfare programs, and ultimately led to significant innovation that reduced welfare dependency from a high of 3.1 million in 1994 to a low of 1.6 million in 2008, while also reducing government spending on social assistance.

The Smith government’s Alberta Next Panel wants the federal government to transfer some of its tax revenues to the provinces and reduce restrictions on provincial program delivery. As Canada’s experience in the 1990s shows, this could spur real innovation that ultimately improves services for Albertans and all Canadians.

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMainstream media missing in action as YouTuber blows lid off massive taxpayer fraud

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLand use will be British Columbia’s biggest issue in 2026

-

International1 day ago

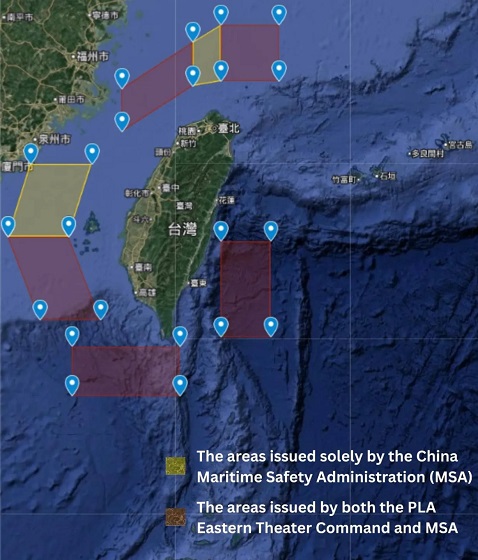

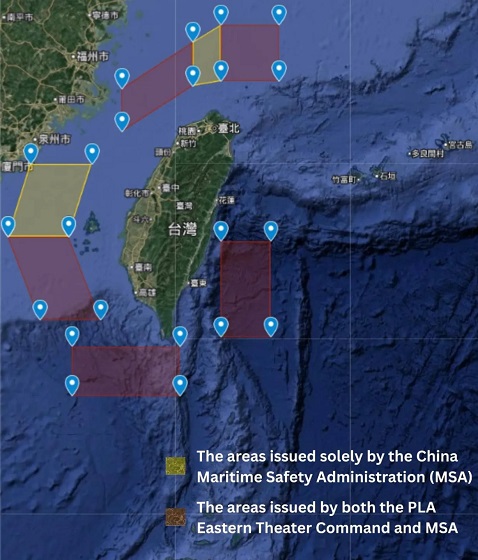

International1 day agoChina Stages Massive Live-Fire Encirclement Drill Around Taiwan as Washington and Japan Fortify

-

Digital ID1 day ago

Digital ID1 day agoThe Global Push for Government Mandated Digital IDs And Why You Should Worry

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoRulings could affect energy prices everywhere: Climate activists v. the energy industry in 2026

-

Business11 hours ago

Business11 hours agoCanada needs serious tax cuts in 2026

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoStripped and shipped: Patel pushes denaturalization, deportation in Minnesota fraud