Addictions

BC NDP, Conservatives’ drug policies converge in close election

From Break The Needle

By Alexandra Keeler

The BC NDP and Conservatives have both pledged to introduce involuntary care for addicts as they contend for voter support on unpopular issue

Gregory Sword has been advocating for British Columbia to permit involuntary care of individuals struggling with addiction ever since losing his 14-year-old daughter to an overdose two years ago.

Now, he looks likely to get his wish — regardless of which party wins the provincial election on Oct. 19.

On Sept. 15, NDP Premier David Eby announced plans to expand involuntary care for “people with addiction challenges, brain injuries, and mental-health issues.” The announcement follows a similar pledge by BC Conservative Leader John Rustad, who on Sept. 11 promised to introduce involuntary care for adults and minors.

The move suggests the BC NDP may be recalibrating its drug policies in response to polling data and competitive pressure from the BC Conservative Party, which has seen its electoral prospects bolstered by the collapse of the centre-right BC United Party.

The BC Conservatives and BC NDP are tied in the polls, at 44 and 43 per cent respectively, according to an Aug. 30 Angus Reid survey. More than two-thirds of respondents said they thought the province was on the “wrong track” in dealing with the opioid crisis. A Sept. 5 Angus Reid poll had similar findings, with 74 per cent of respondents rating the NDP’s handling of the drug crisis as “poor” or “very poor.”

‘A new phase’

B.C. saw a six per cent drop in opioid-related deaths in early 2024 compared to 2023. But the province continues to account for 32 per cent of all drug-related deaths in Canada, despite having just 13 per cent of its population.

In Sunday’s announcement, Eby referred to the introduction of involuntary care as “the beginning of a new phase of our response to the addiction crisis … We are taking action to get them the care they need to keep them safe, and in doing so, keep our communities safe, too.”

Rustad criticized the announcement, citing policy inconsistency. “For years, the NDP ignored the calls for involuntary care, leaving families helpless and those suffering on the streets,” he said in a media release.

“Now, after our party clearly outlined a plan to bring compassion and accountability to addiction treatment, Eby is suddenly pretending to be on board.”

However, Eby first proposed introducing involuntary care in August 2022 during his leadership race. The NDP’s move also partially follows a recommendation of Dr. Daniel Vigo, B.C.’s first chief scientific adviser for psychiatry, who was appointed to that role in June 2024.

Sword, who tried to get his daughter help, believes B.C.’s youth treatment framework — which currently requires minors to consent to addictions treatment — ultimately contributed to his daughter’s death.

“This is how screwed up B.C. is: If I harm my child, beat my child, get my child drugs — she can be taken away from me and get the help that she needs,” he told Canadian Affairs in August. “But if she’s doing it to herself, it’s okay.”

Bold harm-reduction measures

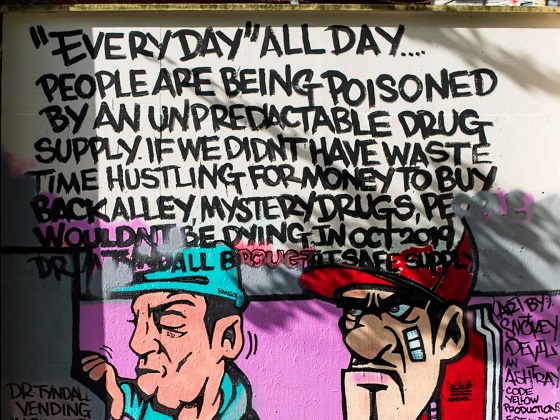

The “new phase” in the NDP’s response to the drug crisis reflects a shift from a prior focus on bold harm-reduction measures — some of which have been followed by reversals.

Since taking office in 2017, the NDP has doubled the number of supervised consumption sites in B.C., from three to six (five are currently operational). And it has expanded the number of overdose prevention sites — which generally offer fewer services than supervised consumption sites — from 20 to 44.

In 2020, the NDP government introduced prescribed alternative supply programs — previously known as “safer supply” — which enable users to receive prescribed opioids as an alternative to illicit street drugs.

In January 2023, the province began a three-year, trial decriminalization project that permitted British Columbians to possess small amounts of otherwise illicit drugs such as heroin, fentanyl, and methamphetamine. B.C. was the first — and so far only — province to decriminalize hard drugs.

But in April, the province partially reversed course, obtaining Ottawa’s approval to recriminalize the use of hard drugs in public spaces.

In October 2023, Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry ordered that vending machines be installed outside hospital emergency departments on Vancouver Island to dispense free drug consumption supplies. On Sept. 12, Eby ordered a review of this initiative, leading to a suspension of the machines until the review is complete.

The BC NDP party did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story by press time.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

Conservative alternatives

The BC Conservatives have positioned themselves as champions of “common sense” solutions to the drug crisis. In response to requests for comment for this story, the BC Conservatives referred Canadian Affairs to its Sept. 15 media release.

Rustad has said that safe supply programs and decriminalization have been policy failures. The party’s platform pledges to “end heroin hand-outs” and to “reverse decriminalization of hard drugs.” Rustad has also criticized harm-reduction vending machines, accusing Eby of “encouraging the proliferation of hard drug use across the province.”

“I know that they [BC Conservatives] are very much on board for more recovery models versus drug decriminalization,” said William Yoachim, a Nanaimo city council member and member of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. Yoachim says he is cautiously optimistic there could be a significant policy change under a new government.

“My only concern with what a Conservative government’s approach would be is their leader. I’m not sure how committed he would be towards the Indigenous recovery.”

The BC Conservatives have said they would develop a new public health strategy focused on addressing “the root causes of drug addiction that prioritizes treatment and not free drugs.”

They have also proposed stricter penalties for drug smuggling and enhanced border security.

Before suspending its electoral campaign, the BC United Party had pledged to introduce free, accessible mental health and addiction services and longer treatment stays. It had also advocated for people with lived experience of addiction, homelessness and mental illness to be involved in designing recovery-oriented housing.

It remains unclear whether the BC Conservatives — which now includes some former BC United candidates — will adopt any of these policies.

Sarah Blyth, a frontline harm-reduction worker with the Vancouver Overdose Prevention Society, says she is frustrated by how polarizing the issue of drug policy has become.

“People are becoming really dogmatic on either side of it,” she said. “We should be looking at each other to see what unique, creative approaches we’re taking … and figure out what’s working where, and do our best.”

Blyth says she plans to keep her head down through this election. “Let them fight it out.”

“Let this be over, and then let’s get back to work.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Four new studies show link between heavy cannabis use, serious health risks

Cannabis products purchased in Ontario and B.C., including gummies, pre-rolled joints, chocolates and dried flower; April 11, 2025. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

By Alexandra Keeler

New Canadian research shows a connection between heavy cannabis use and dementia, heart attacks, schizophrenia and even death

Six months ago, doctors in Boston began noticing a concerning trend: young patients were showing up in emergency rooms with atypical symptoms and being diagnosed with heart attacks.

“The link between them was that they were heavy cannabis users,” Dr. Ahmed Mahmoud, a cardiovascular researcher and physician in Boston, told Canadian Affairs in an interview.

These frontline observations mirror emerging evidence by Canadian researchers showing heavy cannabis use is associated with significant adverse health impacts, including heart attacks, schizophrenia and dementia.

Sources warn public health measures are not keeping pace with rapid changes to cannabis products as the market is commercialized.

“The irony of this moment is that society’s risk perception of cannabis is at an all-time low, at the exact moment that the substance is probably having increasingly negative health impacts,” said Dr. Daniel Myran, a physician and Canada Research Chair at the University of Ottawa. Myran was lead researcher on three new Canadian studies on cannabis’ negative health impacts.

Legalization

Canada was the first G7 country to create a commercial cannabis market when it legalized the production and sale of cannabis in 2018.

The drug is now widely used in Canada.

In the 2024 Canadian Cannabis Survey, an annual government survey of cannabis trends, 26 per cent of respondents said they used cannabis for non-medical purposes in the past year, up from 22 per cent in 2018. Among youth, that number was 41 per cent.

Health Canada’s website warns that cannabis use can lower blood pressure and raise heart rates, which can increase the risk of a heart attack. But the warnings on cannabis product labels vary. Some mention risks of anxiety or effects on memory and concentration, but make no mention of cardiovascular risks.

The annual cannabis survey also shows a significant percentage of Canadians remain unaware of cannabis’ health risks.

In the survey, only 70 per cent of respondents said they had enough reliable information to make informed decisions about cannabis use. And 50 per cent of respondents said they had not seen any education campaigns or public health messages about cannabis.

At the same time, researchers are finding mounting evidence that cannabis use is associated with health risks.

A 2023 study by researchers at the University of Calgary, the University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services found that adults with cannabis use disorder faced a 60 per cent higher risk of experiencing adverse cardiovascular events — including heart attacks. Cannabis use disorder is marked by the inability to stop using cannabis despite negative consequences, such as work, social, legal or health issues.

Between February and April of this year, three other Canadian studies linked frequent cannabis use to elevated risks of developing schizophrenia, dementia and mortality. These studies were primarily conducted by researchers at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and ICES uOttawa (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences).

“These results suggest that individuals who require hospital-based care for a [cannabis use disorder] may be at increased risk of premature death,” said the study linking cannabis-related hospital visits with increased mortality rates.

The three 2024 studies all examined the impacts of severe cannabis use, suggesting more moderate users may face lower risks. The researchers also cautioned that their research shows a correlation between heavy cannabis use and adverse health effects, but does not establish causality.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Budtenders

Health experts say they are troubled by the widespread perception that cannabis is entirely benign.

“It has some benefits, it has some side effects,” said Mahmoud, the Boston cardiovascular researcher. “We need to raise awareness about the side effects as well as the benefits.”

Some also expressed concern that the commercialization of cannabis products in Canada has created a race to produce products with elevated levels of THC, the main psychoactive compound that produces a “high.”

THC levels have more than doubled since legalization, yet even products with high THC levels are marketed as harmless.

“The products that are on the market are evolving in ways that are concerning,” Myran said. “Higher THC products are associated with considerably more risk.”

Myran views cannabis decriminalization as a public health success, because it keeps young people out of the criminal justice system and reduces inequities faced by Indigenous and racialized groups.

“[But] I do not think that you need to create a commercial cannabis market or industry in order to achieve those public health benefits,” he said.

Since decriminalization, the provinces have taken different approaches to regulating cannabis. But even in provinces where governments control cannabis distribution, such as New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, products with high THC levels dominate retail shelves and online storefronts.

In Myran’s view, federal and provincial governments should instead be focused on curbing harmful use patterns, rather than promoting cannabis sales.

Ian Culbert, executive director of the Canadian Public Health Association, thinks governments’ financial interest in the cannabis industry creates a conflict of interest.

“[As with] all regulated substances, governments are addicted to the revenue they create,” he said. “But they also have a responsibility to safeguard the well-being of citizens.”

Culbert believes cannabis retailers should be required to educate customers about health risks — just as bartenders are required to undergo Smart Serve training and lottery corporations are required to mitigate risks of gambling addiction.

“Give ‘budtenders’ the training around potential health risks,” he said.

“While cannabis may not be the cause of some of these negative health events … it is the intersection at which an intervention can take place through the transaction of sales. So is there something we can do there that can change the trajectory of a person’s life?”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

2025 Federal Election

Study links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

By Alexandra Keeler

A study links B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization to more opioid hospitalizations, but experts note its limitations

A new study says B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may have failed to reduce overdoses. Furthermore, the very policies designed to help drug users may have actually increased hospitalizations.

“Neither the safer opioid supply policy nor the decriminalization of drug possession appeared to mitigate the opioid crisis, and both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations,” the study says.

The study has sparked debate, with some pointing to it as proof that B.C.’s drug policies failed. Others have questioned the study’s methodology and conclusions.

“The question we want to know the answer to [but cannot] is how many opioid hospitalizations would have occurred had the policy not have been implemented,” said Michael Wallace, a biostatistician and associate professor at the University of Waterloo.

“We can never come up with truly definitive conclusions in cases such as this, no matter what data we have, short of being able to magically duplicate B.C.”

Jumping to conclusions

B.C.’s controversial safer supply policies provide drug users with prescription opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs. Its decriminalization policy permitted drug users to possess otherwise illegal substances for personal use.

The peer-reviewed study was led by health economist Hai Nguyen and conducted by researchers from Memorial University in Newfoundland, the University of Manitoba and Weill Cornell Medicine, a medical school in New York City. It was published in the medical journal JAMA Health Forum on March 21.

The researchers used a statistical method to create a “synthetic” comparison group, since there is no ideal control group. The researchers then compared B.C. to other provinces to assess the impact of certain drug policies.

Examining data from 2016 to 2023, the study links B.C.’s safer supply policies to a 33 per cent rise in opioid hospitalizations.

The study says the province’s decriminalization policies further drove up hospitalizations by 58 per cent.

“Neither the safer supply policy nor the subsequent decriminalization of drug possession appeared to alleviate the opioid crisis,” the study concludes. “Instead, both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations.”

The B.C. government rolled back decriminalization in April 2024 in response to widespread concerns over public drug use. This February, the province also officially acknowledged that diversion of safer supply drugs does occur.

The study did not conclusively determine whether the increase in hospital visits was due to diverted safer supply opioids, the toxic illicit supply, or other factors.

“There was insufficient evidence to conclusively attribute an increase in opioid overdose deaths to these policy changes,” the study says.

Nguyen’s team had published an earlier, 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine that also linked safer supply to increased hospitalizations. However, it failed to control for key confounders such as employment rates and naloxone access. Their 2025 study better accounts for these variables using the synthetic comparison group method.

The study’s authors did not respond to Canadian Affairs’ requests for comment.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Correlation vs. causation

Chris Perlman, a health data and addiction expert at the University of Waterloo, says more studies are needed.

He believes the findings are weak, as they show correlation but not causation.

“The study provides a small signal that the rates of hospitalization have changed, but I wouldn’t conclude that it can be solely attributed to the safer supply and decrim[inalization] policy decisions,” said Perlman.

He also noted the rise in hospitalizations doesn’t necessarily mean more overdoses. Rather, more people may be reaching hospitals in time for treatment.

“Given that the [overdose] rate may have gone down, I wonder if we’re simply seeing an effect where more persons survive an overdose and actually receive treatment in hospital where they would have died in the pre-policy time period,” he said.

The Nguyen study acknowledges this possibility.

“The observed increase in opioid hospitalizations, without a corresponding increase in opioid deaths, may reflect greater willingness to seek medical assistance because decriminalization could reduce the stigma associated with drug use,” it says.

“However, it is also possible that reduced stigma and removal of criminal penalties facilitated the diversion of safer opioids, contributing to increased hospitalizations.”

Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, is more critical.

“The [study’s] findings do not warrant the conclusion that these policies are causally associated with increased hospitalization or overdose,” said Urbanoski, who also holds the Canada Research Chair in Substance Use, Addictions and Health Services.

Her team published a study in November 2023 that measured safer supply’s impact on mortality and acute care visits. It found safer supply opioids did reduce overdose deaths.

Critics, however, raised concerns that her study misrepresented its underlying data and showed no statistically significant reduction in deaths after accounting for confounding factors.

The Nguyen study differs from Urbanoski’s. While Urbanoski’s team focused on individual-level outcomes, the Nguyen study analyzed broader, population-level effects, including diversion.

Wallace, the biostatistician, agrees more individual-level data could strengthen analysis, but does not believe it undermines the study’s conclusions. Wallace thinks the researchers did their best with the available data they had.

“We do not have a ‘copy’ of B.C. where the policies weren’t implemented to compare with,” said Wallace.

B.C.’s overdose rate of 775 per 100,000 is well above the national average of 533.

Elenore Sturko, a Conservative MLA for Surrey-Cloverdale, has been a vocal critic of B.C.’s decriminalization and safer supply policies.

“If the government doesn’t want to believe this study, well then I invite them to do a similar study,” she told reporters on March 27.

“Show us the evidence that they have failed to show us since 2020,” she added, referring to the year B.C. implemented safer supply.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMark Carney: Our Number-One Alberta Separatist

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoNine Dead After SUV Plows Into Vancouver Festival Crowd, Raising Election-Eve Concerns Over Public Safety

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoJeffrey Epstein accuser Virginia Giuffre reportedly dies by suicide

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoColumnist warns Carney Liberals will consider a home equity tax on primary residences

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCanada is squandering the greatest oil opportunity on Earth

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoU.S. Army names new long-range hypersonic weapon ‘Dark Eagle’

-

Autism21 hours ago

Autism21 hours agoUK plans to test children with gender confusion for autism

-

COVID-1920 hours ago

COVID-1920 hours agoFormer Australian state premier accused of lying about justification for COVID lockdowns