Aristotle Foundation

At Toronto Metropolitan University medical school, some students are more equal than others

READ THE REALITY CHECK

By Bruce Pardy

A new Aristotle Foundation Reality Check from Queen’s University law professor Bruce Pardy details how Canada’s courts reinterpreted even the clear equality clause in the constitution to read in anti-individual “equity.” That hollowed out a founding Canadian principle of equality before the law.

|

|

|

Aristotle Foundation

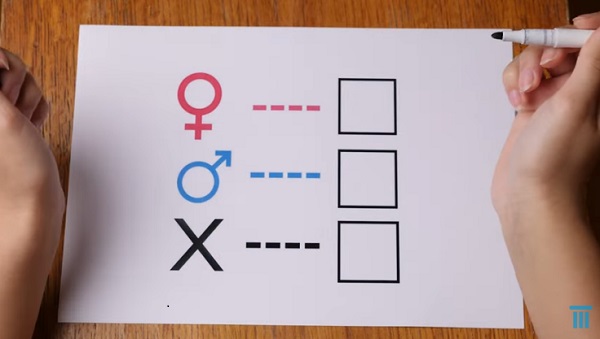

Canada has the world’s MOST relaxed gender policy for minors

Are Canada and the United States out-of-step on gender policy for minors?

READ the new study by the Aristotle Foundation and Do No Harm: https://aristotlefoundation.org/study…

|

Aristotle Foundation

Toronto cancels history, again: The irony and injustice of renaming Yonge-Dundas Square to Sankofa Square

From the Aristotle Foundation

By

In 2022, Torontonians renamed Ryerson University to Toronto Metropolitan University, “to address the legacy of Egerton Ryerson.”1 Rather than remember him as the founder of Ontario’s system of “free” public schools and libraries, Ryerson was “cancelled” for his suggestions regarding the curriculum for the Indian residential schools that were then being proposed. However, the schools themselves were not built until some 30 years later, after Ryerson was dead. Further, modern complaints about the schools are generally misconceived and have little to do with the curriculum.2

In 2024, Toronto is at it again. This time, the historical figure targeted for cancellation is abolitionist Henry Dundas, as city officials seek to wipe his name from Yonge-Dundas Square. The square is a notable city landmark and one of Canada’s most popular tourist destinations. Filled with brightly lit electronic advertisement billboards, the square serves as an iconic social hub and venue for events connected to Toronto’s cultural festivals. The city’s former mayor, John Tory, summarized the case for renaming the famous square – based on a report from city hall – as follows:

An objective reading of the history, the significance of this street which crosses our city, the fact that Mr. Dundas had virtually no connection to Toronto and our strong commitment to equity, inclusion and reconciliation make this a unique and symbolically important change.3

The new name, “Sankofa Square,” is taken not from anything Torontonian, Ontarian, or even Canadian – but from the Akan people of West Africa.

Ironically, city officials not only appear ignorant of Henry Dundas’ many contributions to Canada, and to the abolition of slavery, but are also blissfully unaware that the Akan people of Africa were notorious slave traders responsible for capturing and selling one to two million of their fellow Africans into slavery.4

The man: Who was Henry Dundas?

Henry Dundas was a Scottish lawyer, politician, and one of British Prime Minister William Pitt’s most trusted and powerful ministers who served during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars.

Critically, Dundas was also a staunch abolitionist, committed to ending slavery as an institution in the British Empire and elsewhere in the world.

As early as 1777, when he was in his thirties, Dundas publicly established his abolitionist position on slavery. When Joseph Knight, a slave from Jamaica, was taken to Scotland by his owner, he challenged his status as a slave under Scottish law. Dundas, then Lord Advocate (principal legal advisor to the government), took on Knight’s case in his private capacity as a lawyer. On the final appeal before Scotland’s highest court, Dundas argued passionately, and with some humour, against the inhumanity of slavery:

We may possibly see the master chastising his slave as he does his ox or his horse. Perhaps, too, he may shoot him when he turns old […]

[But] [h]uman nature, my Lords, spurns at the thought of slavery among any part of our species.5

The court agreed and declared that no slave could remain a slave once they arrived on Scottish soil.6

A decade later, a religiously-inspired Christian abolition movement began in Britain (most famously personified by William Wilberforce) with the goal of ending the Atlantic slave trade. Dundas was a supporter of the movement, but urged that its members go further and challenge not just the Atlantic slave trade but seek the abolition of slavery itself – a much bigger challenge since at that time slavery was practiced on every inhabited continent.

During the 300 or more years the transatlantic slave trade existed, estimates are that 10 million to 12 million Africans were captured, enslaved, and sold by their fellow Africans. The purchasers were largely British, Portuguese, and French traders who acted as intermediaries in shipping slaves to the Americas for re-sale. The destination for 50 percent of the slaves was South America, 45 percent went to the West Indies, and about four percent went to what would become the United States.7,8 Dundas understood that, unless slavery itself was ended – with its unrelenting violence, forced labour, and premature death – slavery as an institution would continue for generations, since legally the children of slaves were considered chattel (like livestock) and were thus also slaves like their parents.

The controversy: Did Dundas’ abolitionism go far enough?

Dundas is criticized today for amending a motion in Britain’s Parliament in 1792.9 His original motion called for the immediate end to the slave trade. But outright abolition was unrealistic at the time, and thus historians agree that Dundas’ original motion would surely have failed.10 Moreover, Britain’s competitors – especially the Portuguese and French – would have simply picked up where Britain left off. Realizing this, Dundas made a strategic pivot and called for a gradual end to the slave trade. His strategy worked, and his amended motion succeeded with a significant majority.11

Change would take time. Only about one percent of the adult population had the right to vote,12 and many had at least an indirect financial interest in West Indian plantations (as did numerous Members of Parliament), and trade with the plantations generated income for businesses in England and tariff revenue for the Crown. Surmounting such entrenched interests would not happen overnight.

And this is why Dundas’ successful motion was key: it shifted the tenor of the public discourse. For the first time, ending the slave trade was up for debate. The British empire at this time was nearing its peak as the largest empire in history, with enormous influence, and thus this step was significant in the eventual abolition of slavery worldwide.

The Toronto connection: Dundas the humanitarian

For his role in abolishing slavery, Dundas ought to be celebrated. The same is true of his major influence on the colonies that would become Canada and, in particular, on what would become the province of Ontario and the city of Toronto. Importantly, that influence was wielded in support of issues that, today, would be described as relating to equity, inclusion, and reconciliation—ironically, the exact criteria (“commitments”) justifying the city’s condemnation of him.

Appointing Simcoe, the empire’s first legislator to outlaw slavery

Dundas was a close friend of John Graves Simcoe (another staunch abolitionist), and he appointed Simcoe as the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada in 1791. It was Simcoe who, two years later, would introduce the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada, the very first legislation in the entire British empire to limit slavery.14

The legislation passed, beginning the abolition of slavery in the province. Although the legislation did not free slaves already present, it freed the children of such slaves at age 25, and made Upper Canada a safe haven for slaves fleeing the United States.15 Like the precedent Dundas set in Scotland, no slave could remain a slave on Upper Canadian soil. Over the next seven decades, more than 40,000 black men and women would risk their lives to escape slavery and find freedom in Upper Canada.

When Dundas appointed Simcoe, he knew about Simcoe’s abolitionist sympathies—and almost certainly anticipated the legislation he would propose.16 And thus, Dundas made possible what became known as the Underground Railroad.

Honouring black soldiers

Dundas also ordered the governors of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to honour Britain’s promise of land grants to 4,000 former slaves who had fought for the British against the American Revolution, and to offer free passage – courtesy of the British navy – to any who preferred to return to Africa.17

Initiating official bilingualism

Upon the division of the then-province of Quebec into Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) and Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) in 1791, Dundas instructed the English governor of Lower Canada to allow French-speaking parliamentarians to pass laws in French.18 This was a serious point of disagreement in the newly formed legislative assembly, as the (powerful) English minority insisted all British subjects be governed in English. Dundas solved the impasse by ordering that legislation be passed in both languages, in what is the first example of official bilingualism in Canadian history. (For context, this occurred only months after England and France were, once again, at war; and thus this act was truly magnanimous.)19

Defending indigenous peoples

Finally, following American Independence, Yankee incursions into Canadian territory were a very real and constant threat. Dundas, as secretary of state for Home Affairs, instructed the Canadian governor Sir Guy Carleton to intervene against the Americans and protect the interests of the “Indian Nations”:

…securing to them the peaceable and quiet possession of the Lands which they have hitherto occupied as their hunting Grounds, and such others as may enable them to procure a comfortable subsistence for themselves and their families.20

The irony: Replacing the abolitionist with slave traders

Given the evidence, Toronto city council’s treatment of Dundas is clearly not only ahistorical but shameful. Regrettably, so is their adoption of the replacement, the term “Sankofa” from the Akan language. Little needs to be said here, other than this: The Akan peoples of West Africa were notorious slave traders. During the transatlantic slave trade, the Akan captured, enslaved, and sold one to two million fellow Africans into slavery. In other words, the Akan were the source of 10 to 20 percent of all transatlantic slaves.

Conclusion

The Toronto city council narrative surrounding the renaming of Yonge-Dundas Square flies in the face of historical fact. Dundas was demonstrably ahead of his time as a humanitarian. And as a politician, he was not only principled and morally courageous but effective. Dundas was one of the key figures in abolishing the slave trade, opening up the Underground Railroad, and protecting minorities of various backgrounds—black, French, and indigenous. If the city really wants to promote the act of “reflecting on and reclaiming teachings from the past,”21 as it claims, it might do well to start with the truth about Henry Dundas’ legacy. There may be times to rename a place or landmark, but this is not one of them.

Endnotes

About the author

Greg Piasetzki is a Toronto-based intellectual property lawyer, a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, and a citizen of the Métis Nation of Ontario.

About the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

-

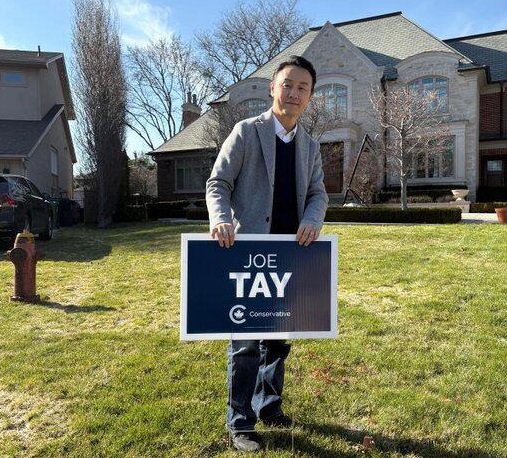

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoTrump Has Driven Canadians Crazy. This Is How Crazy.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoThe Anhui Convergence: Chinese United Front Network Surfaces in Australian and Canadian Elections

-

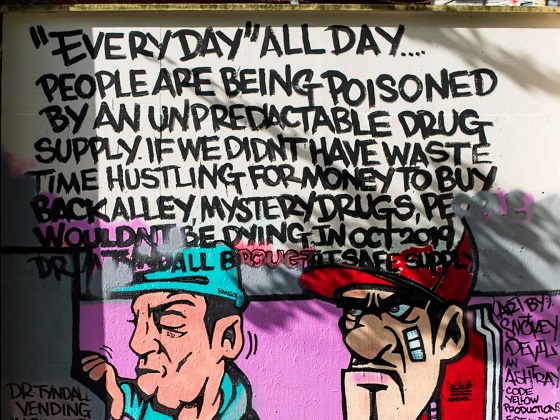

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoStudy links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoHyundai moves SUV production to U.S.

-

Entertainment1 day ago

Entertainment1 day agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoWhen it comes to pipelines, Carney’s words flow both ways

-

2025 Federal Election22 hours ago

2025 Federal Election22 hours agoAs PM Poilievre would cancel summer holidays for MP’s so Ottawa can finally get back to work

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPolls say Canadians will give Trump what he wants, a Carney victory.