Addictions

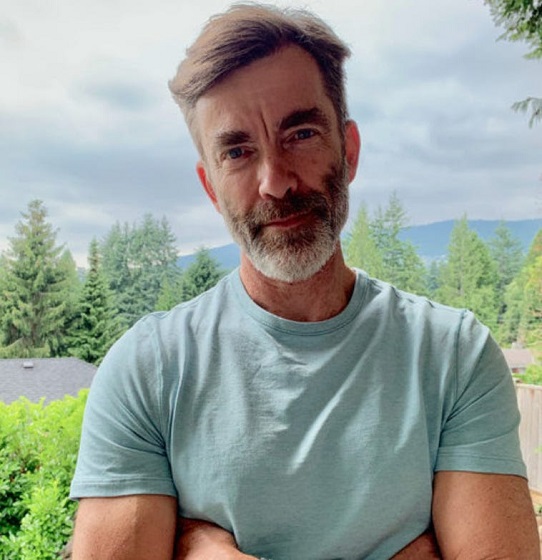

BC Addictions Expert Questions Ties Between Safer Supply Advocates and For-Profit Companies

By Liam Hunt

Canada’s safer supply programs are “selling people down the river,” says a leading medical expert in British Columbia. Dr. Julian Somers, director of the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction at Simon Fraser University, says that despite the thin evidence in support of these experimental programs, the BC government has aggressively expanded them—and retaliated against dissenting researchers.

Somers also, controversially, raises questions about doctors and former health officials who appear to have gravitated toward businesses involved in these programs. He notes that these connections warrant closer scrutiny to ensure public policies remain free from undue industry influence.

Safer supply programs claim to reduce overdoses and deaths by distributing free addictive drugs—typically 8-milligram tablets of hydromorphone, an opioid as potent as heroin—to dissuade addicts from accessing riskier street substances. Yet, a growing number of doctors say these programs are deeply misguided—and widely defrauded.

Ultimately, Somers argues, safer supply is exacerbating the country’s addiction crisis.

Somers opposed safer supply at its inception and openly criticized its nationwide expansion in 2020. He believes these programs perpetuate drug use and societal disconnection and fail to encourage users to make the mental and social changes needed to beat addiction. Worse yet, the safer supply movement seems rife with double standards that devalue the lives of poorer drug users. While working professionals are provided generous supports that prioritize recovery, disadvantaged Canadians are given “ineffective yet profitable” interventions, such as safer supply, that “convey no expectation that stopping substance use or overcoming addiction is a desirable or important goal.”

To better understand addiction, Somers created the Inter-Ministry Evaluation Database (IMED) in 2004, which, for the first time in BC’s history, connected disparate information—i.e. hospitalizations, incarceration rates—about vulnerable populations.

Throughout its existence, health experts used IMED’s data to create dozens of research projects and papers. It allowed Somers to conduct a multi-million-dollar randomized control trial (the “Vancouver at Home” study) that showed that scattering vulnerable people into regular apartments throughout the city, rather than warehousing them in a few buildings, leads to better outcomes at no additional cost.

In early 2021, Somers presented recommendations drawn from his analysis of the IMED to several leading officials in the B.C. government. He says that these officials gave a frosty reception to his ideas, which prioritized employment, rehabilitation, and social integration over easy access to drugs. Shortly afterwards, the government ordered him to immediately and permanently delete the IMED’s ministerial data.

Somers describes the order as a “devastating act of retaliation” and says that losing access to the IMED effectively ended his career as a researcher. “My lab can no longer do the research we were doing,” he noted, adding that public funding now goes exclusively toward projects sympathetic to safer supply. The B.C. government has since denied that its order was politically motivated.

In early 2022, the government of Alberta commissioned a team of researchers, led by Somers, to investigate the evidence base behind safer supply. They found that there was no empirical proof that the experiment works, and that harm reduction researchers often advocated for safer supply within their studies even if their data did not support such recommendations.

Somers says that, after these findings were published, his team was subjected to a smear campaign that was partially organized by the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU), a powerful pro-safer supply research organization with close ties to the B.C. government. The BCCSU has been instrumental in the expansion of safer supply and has produced studies and protocols in support of it, sometimes at the behest of the provincial government.

Somers is also concerned about the connections between some of safer supply’s key proponents and for-profit drug companies.

He notes that the BCCSU’s founding executive director, Dr. Evan Wood, became Chief Medical Officer at Numinus Wellness, a publicly traded psychedelic company, in 2020. Similarly, Dr. Perry Kendall, who also served as a BCCSU executive director, went on to found Fair Price Pharma, a now-defunct for-profit company that specializes in providing pharmaceutical heroin to high-risk drug users, the following year.

While these connections are not necessarily unethical, they do raise important questions about whether there is enough industry regulation to minimize potential conflicts of interest, whether they be real or perceived.

The BCCSU was also recently criticized in an editorial by Canadian Affairs, which noted that the organization had received funding from companies such as Shoppers Drug Mart and Tilray (a cannabis company). The editorial argued that influential addiction research organizations should not receive drug industry funding and reported that Alberta founded its own counterpart to the BCCSU in August, known as the Canadian Centre of Recovery Excellence, which is legally prohibited from accepting such sponsorships.

Already, private interests are betting on the likely expansion of safer supply programs. For instance, Safe Supply Streaming Co., a publicly traded venture capital firm, has advertised to potential investors that B.C.’s safer supply system could create a multi-billion-dollar annual market.

Somers believes that Canada needs more transparency regarding how for-profit companies may be directly or indirectly influencing policy makers: “We need to know exactly, to the dollar, how much of [harm reduction researchers’] operating budget is flowing from industry sources.”

Editor’s note: This story is published in syndication with Break The Needle and Western Standard.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Dr. Julian M. Somers is director of the Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction at Simon Fraser University. He was Director of the UBC Psychology Clinic, and past president of the BC Psychological Association. Liam Hunt is a contributing author to the Centre For Responsible Drug Policy in partnership with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Addictions

New RCMP program steering opioid addicted towards treatment and recovery

News release from Alberta RCMP

Virtual Opioid Dependency Program serves vulnerable population in Red Deer

Since April 2024, your Alberta RCMP’s Community Safety and Well-being Branch (CSWB) has been piloting the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program (VODP) program in Red Deer to assist those facing opioid dependency with initial-stage intervention services. VODP is a collaboration with the Government of Alberta, Recovery Alberta, and the Alberta RCMP, and was created to help address opioid addiction across the province.

Red Deer’s VODP consists of two teams, each consisting of a police officer and a paramedic. These teams cover the communities of Red Deer, Innisfail, Blackfalds and Sylvan Lake. The goal of the program is to have frontline points of contact that can assist opioid users by getting them access to treatment, counselling, and life-saving medication.

The Alberta RCMP’s role in VODP:

- Conducting outreach in the community, on foot, by vehicle, and even UTV, and interacting with vulnerable persons and talking with them about treatment options and making VODP referrals.

- Attending calls for service in which opioid use may be a factor, such as drug poisonings, open drug use in public, social diversion calls, etc.

- Administering medication such as Suboxone and Sublocade to opioid users who are arrested and lodged in RCMP cells and voluntarily wish to participate in VODP; these medications help with withdrawal symptoms and are the primary method for treating opioid addiction. Individuals may be provided ongoing treatment while in police custody or incarceration.

- Collaborating with agencies in the treatment and addiction space to work together on client care. Red Deer’s VODP chairs a quarterly Vulnerable Populations Working Group meeting consisting of a number of local stakeholders who come together to address both client and community needs.

While accountability for criminal actions is necessary, the Alberta RCMP recognizes that opioid addiction is part of larger social and health issues that require long-term supports. Often people facing addictions are among offenders who land in a cycle of criminality. As first responders, our officers are frequently in contact with these individuals. We are ideally placed to help connect those individuals with the VODP. The Alberta RCMP helps those individuals who wish to participate in the VODP by ensuring that they have access to necessary resources and receive the medical care they need, even while they are in police custody.

Since its start, the Red Deer program has made nearly 2,500 referrals and touchpoints with individuals, discussing VODP participation and treatment options. Some successes of the program include:

- In October 2024, Red Deer VODP assessed a 35-year-old male who was arrested and in police custody. The individual was put in contact with medical care and was prescribed and administered Suboxone. The team members did not have any contact with the male again until April 2025 when the individual visited the detachment to thank the team for treating him with care and dignity while in cells, and for getting him access to treatment. The individual stated he had been sober since, saying the treatment saved his life.

- In May 2025, the VODP team worked with a 14-year-old female who was arrested on warrants and lodged in RCMP cells. She had run away from home and was located downtown using opioids. The team spoke to the girl about treatment, was referred to VODP, and was administered Sublocade to treat her addiction. During follow-up, the team received positive feedback from both the family and the attending care providers.

The VODP provides same-day medication starts, opioid treatment transition services, and ongoing opioid dependency care to people anywhere in Alberta who are living with opioid addiction. Visit vodp.ca to learn more.

“This collaboration between Alberta’s Government, Recovery Alberta and the RCMP is a powerful example of how partnerships between health and public safety can change lives. The Virtual Opioid Dependency Program can be the first step in a person’s journey to recovery,” says Alberta’s Minister of Mental Health and Addiction Rick Wilson. “By connecting people to treatment when and where they need it most, we are helping build more paths to recovery and to a healthier Alberta.”

“Part of the Alberta RCMP’s CSWB mandate is the enhancement of public safety through community partnerships,” says Supt. Holly Glassford, Detachment Commander of Red Deer RCMP. “Through VODP, we are committed to building upon community partnerships with social and health agencies, so that we can increase accessibility to supports in our city and reduce crime in Red Deer. Together we are creating a stronger, safer Alberta.”

Addictions

Saskatchewan launches small fleet of wellness buses to expand addictions care

By Alexandra Keeler

Across Canada, mobile health models are increasingly being used to offer care to rural and underserved communities

Saskatchewan has launched a small fleet of mobile wellness buses to improve access to primary health care, mental health and addiction services in the province.

The first bus began operating in Regina on Feb. 12. Another followed in Prince Albert on March 21. Saskatoon’s bus was unveiled publicly on April 9. All three are former coach buses that have been retrofitted to provide health care to communities facing barriers to access.

“Mobile health units are proven to improve outcomes for people facing barriers to healthcare,” Kayla DeMong, the executive director of addiction treatment centre Prairie Harm Reduction, told Canadian Affairs in an email.

“We fully support this innovative approach and are excited to work alongside the health bus teams to ensure the people we support receive the care they need, when and where they need it.”

Wellness buses

Like all provinces, Saskatchewan has been grappling with the opioid crisis.

In 2023, an estimated 457 individuals died from overdoses in the province. In 2024, that number fell to 346. But the province continues to struggle with fatal and non-fatal overdoses.

In late February, Saskatoon firefighters responded to more than 25 overdoses in a single 24-hour period. Just over a week later, they responded to 37 overdoses within another 24-hour window.

Saskatchewan’s wellness buses are part of the province’s plan to address these problems. In April 2025, the province announced $2.4 million to purchase and retrofit three coach buses, plus $1.5 million in annual operating funds.

The buses operate on fixed schedules at designated locations around each city. Each bus is staffed with a nurse practitioner, nurse and assessor coordinator who offer services such as overdose reversal kits, addiction medicine and mental health referrals.

“By bringing services directly to where people are, the health buses foster safer, more welcoming spaces and help build trusting relationships between community members and care providers,” said DeMong, executive director of Prairie Harm Reduction.

Saskatoon-based Prairie Harm Reduction is one of the local organizations that partners with the buses to provide additional support services. Prairie Harm Reduction provides a range of family, youth and community supports, and also houses the province’s only fixed supervised consumption site.

The mobile model

Saskatchewan is not the only province using wellness buses. Across Canada, mobile health models are increasingly being used to expand access to care in rural and underserved communities.

In Kingston, Ont., the Street Health Centre operates a retrofitted RV called PORCH (Portable Outreach Care Hub) that serves individuals struggling with homelessness and addiction.

“Our outreach services are extremely popular with our clients and community partners,” Donna Glasspoole, manager at Street Health Centre, said in an emailed statement.

“PORCH hits the road two to three days/week and offers a variety of services, which are dependent on the health care providers and community partners aboard.”

Street Health Centre also has a shuttle service that picks up clients in shelters and brings them to medical clinics or addiction medicine clinics.

The PORCH vehicles are not supported by provincial funding, but instead rely on support from the United Way and other grants. Glasspoole says the centre’s permanent location — which does receive government funding — is more cost-effective to operate.

“The vehicles are expensive to operate and our RV is not great in winter months and requires indoor parking,” she said.

Politically palatable

Many mobile health models currently do not provide controversial services such as supervised drug consumption.

The Saskatchewan Health Authority told Canadian Affairs the province’s new wellness buses will not offer supervised consumption services or safer supply, where drug users are given prescribed opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs.

“There are no plans to provide supervised consumption services from the wellness buses,” Saskatchewan Health Authority spokesperson Courtney Markewich told Canadian Affairs in a phone call.

This limited scope may make mobile services more politically palatable in provinces that have resisted harm reduction measures.

In Ontario, some harm reduction programs have shifted to mobile models following Premier Doug Ford’s decision to suspend supervised consumption services located within 200 metres of schools and daycares.

In April, Toronto Public Health ended operations at its Victoria Street fixed consumption site, replacing it with street outreach and mobile vans.

The Ontario government’s decision to close the sites is part of a broader pivot away from harm reduction. The province is investing $378 million to transition suspended sites into 19 new “HART Hubs” that offer primary care, mental health, addictions treatment and other supports.

Glasspoole says that what matters most is not whether services are provided at fixed or mobile locations, but how care is delivered.

Models that “reduce barriers to care, [are] non-judgemental, and [are staffed by] trauma-informed providers” are what lead more people toward treatment and recovery, she said in her email.

In Saskatchewan, DeMong hopes the province’s new wellness buses help address persistent service gaps and build trust with underserved communities.

“This initiative is a vital step toward filling long-standing gaps in the continuum of care by providing low-barrier, community-based access to health-care services,” she said.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

-

Bruce Dowbiggin7 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin7 hours agoWhat Connor Should Say To Oilers: It’s Not You. It’s Me.

-

Business8 hours ago

Business8 hours agoFederal fiscal anchor gives appearance of prudence, fails to back it up

-

Business6 hours ago

Business6 hours agoThe Passage of Bill C-5 Leaves the Conventional Energy Sector With as Many Questions as Answers

-

Alberta4 hours ago

Alberta4 hours agoAlberta poll shows strong resistance to pornographic material in school libraries

-

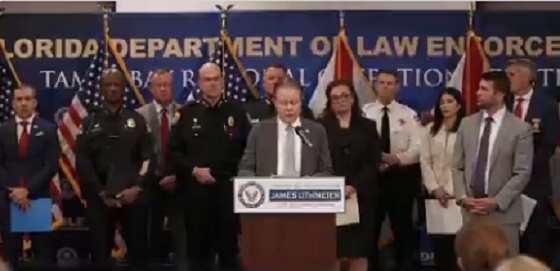

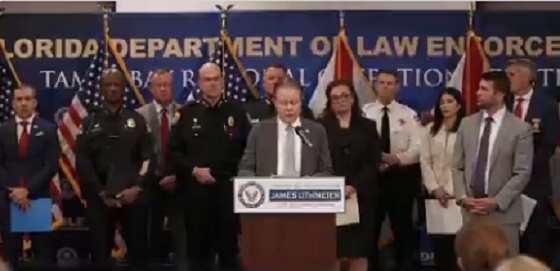

Crime3 hours ago

Crime3 hours agoFlorida rescues 60 missing kids in nation’s largest-ever operation

-

Business2 hours ago

Business2 hours agoCanada should already be an economic superpower. Why is Canada not doing better?

-

Banks5 hours ago

Banks5 hours agoScrapping net-zero commitments step in right direction for Canadian Pension Plan

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoBehind the latest CPI Numbers: Inflation Slows, But Living Costs Don’t