Fraser Institute

Australia’s universal health-care system outperforms Canada on key measures including wait times, costs less and includes large role for private hospitals

The Role of Private Hospitals in Australia’s Universal Health Care System

From the Fraser Institute

by Mackenzie Moir and Bacchus Barua

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial governments across Canada relied on private

clinics in order to deliver a limited number of publicly funded surgeries in a bid to clear unprecedented

surgical backlogs. Subsequently, surveys indicated that 78% of Canadians support allowing more

surgeries and tests performed in private clinics while 40% only support this policy to clear the

surgical backlog. While a majority of Canadians are either supportive (or at the very least curious)

about these arrangements, the use of private clinics continues to be controversial and raise questions

around their compatibility with the provision of universal care.

The reality is that private hospitals play a key role in delivering care to patients in other countries with universal health care. Canada is only one of 30 high-income countries with universal care and many of these countries involve the private-sector in their health-care systems to a wide extent while performing better than Canada.

Australia is one of these countries and routinely outperforms Canada on key indicators of health-care performance while spending at a similar or lower level. Like Canada, Australia ranked

in the top ten for health-care spending (as a percentage of GDP and per capita) in 2020. However, after adjusting for the age of the population, it outperforms Canada on 33 (of 36) measures of performance.

Importantly, Australia outperformed Canada on a number of key measures such as the availability of physicians, nurses, hospital beds, CT scanners, and MRI machines. Australia also outperformed

Canada on every indicator of timely access to care, including ease of access to after-hours care, same-day primary care appointments, and, crucially, timely access to elective surgical care and specialist appointments.

Australia’s universal system is also characterized by a deep integration between the public and private sectors in the financing and delivery of care. Universal health-insurance coverage is provided through its public system known as Medicare. However, Australia also has a large private health-care sector that also finances and delivers medical services. Around half of the Australian population (55.2% in 2021/22) benefit from private health-insurance coverage provided by 33 registered not-for-profit and for-profit private insurance companies.

Private hospitals (for profit and not for profit) made up nearly half (48.5%) of all Australian hospitals in 2016 and contain a third of all care beds. These hospitals are a major partner in the delivery of care in Australia. For example, in 2021/22 41% of all recorded episodes of hospital care occurred in private hospitals. While delivering a small minority of emergency care (8.2%), private hospitals delivered the majority of recorded elective care (58.6%) and 70.3% of elective admissions involving surgery.

Private hospitals primarily deliver care to fully funded public patients in two ways. The first is contracted

care, either through ad hoc inter-hospital contracts or formal programs. Fully publicly funded episodes of care occurring in private hospitals made up 6.4% of all care in private hospitals, while representing 2.6% of all recorded care. The second way is privately delivered care paid for through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. A full 73.5% of care paid for by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs occurred in private hospitals.

It would be easy, however, to underestimate the significance of this public-private partnership by examining only the delivery of care that is fully publicly funded. Privately insured care is also partially subsidized by the government, at a rate of 75% of the public fee. Therefore, in order to understand the full extent of publicly funded or subsidized care in private hospitals, it is helpful to examine private hospital expenditures by the source of funds. In 2019/20, 32.8% of private hospital expenditures came from government sources, 18.2% of which came from private health-insurance rebates. This means that a full

third of private hospital expenditure comes from a range of public sources, including the federal government.

Overall, private hospitals are important partners in the delivery of care within the Australian universal healthcare system. The Australian system outranks Canada’s on a range of performance indicators, while spending less as a percentage of GDP. Further, the integration of private hospitals into the delivery of care, including public care, occurs while maintaining universal access for residents.

Authors:

More from this study

2025 Federal Election

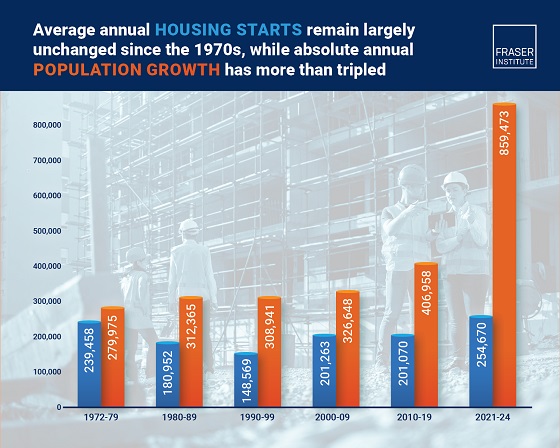

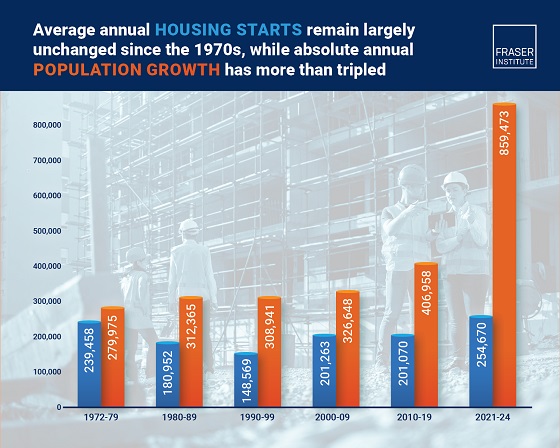

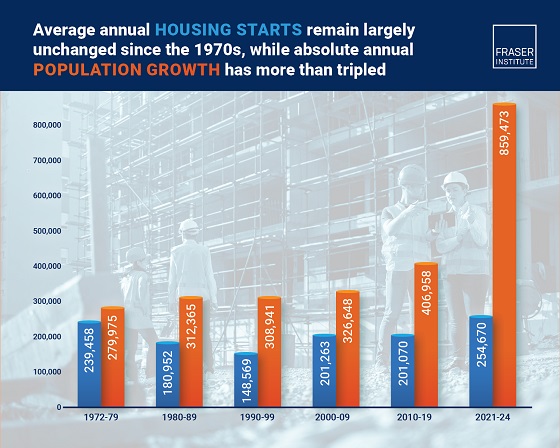

Housing starts unchanged since 1970s, while Canadian population growth has more than tripled

From the Fraser Institute

By: Austin Thompson and Steven Globerman

The annual number of new homes being built in Canada in recent years is virtually the same as it was in the 1970s, despite annual population growth

now being three times higher, finds a new study published today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think tank.

“Despite unprecedented levels of immigration-driven population growth following the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada has failed to ramp up homebuilding sufficiently to meet housing demand,” said Steven Globerman, Fraser Institute senior fellow and co-author of The Crisis in Housing Affordability: Population Growth and Housing Starts 1972–2024.

Between 2021 and 2024, Canada’s population grew by an average of 859,473 people per year, while only 254,670 new housing units were started annually. From 1972 to 1979, a similar number of new housing units were built—239,458—despite the population only growing by 279,975 people a year.

As a result, more new residents are competing for each new home than in the past, which is driving up housing costs.

“The evidence is clear—population growth has been outpacing housing construction for decades, with predictable results,” Globerman said.

“Unless there is a substantial acceleration in homebuilding, a slowdown in population growth, or both, Canada’s housing affordability crisis is unlikely to improve.”

The Crisis in Housing Affordability: Population Growth and Housing Starts 1972–2024

- Canada experienced unprecedented population growth following the COVID-19 pandemic without a commensurately large increase in new homebuilding.

- The imbalance between population growth and new housing construction is reflected in a significant gap between housing demand and supply, which is driving up housing costs.

- Canada’s population grew by a record 1.23 million new residents in 2023 almost entirely due to immigration. That growth was more than double the pre-pandemic record set in 2019.

- Population growth slowed to 951,517 in 2024, still well above any year before 2023.

- Nationally, construction began on about 245,367 new housing units in 2024, down from a recent high of 271,198 starts in 2021—Canada’s annual number of housing starts peaked at 273,203 in 1976.

- Canada’s annual number of housing starts regularly exceeded 200,000 in past decades, when absolute population growth was much lower.

- In 2023, Canada added 5.1 new residents for every housing unit started, which was the highest ratio over the study’s timeframe and well above the average rate of 1.9 residents for every unit started observed over the study period (1972–2024).

- This ratio improved modestly in 2024, with 3.9 new residents added per housing start. However, the ratio remains far higher than at any point prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- These national trends are broadly mirrored across all 10 provinces, where annual population growth relative to housing starts is, to varying degrees, elevated when compared to long-run averages.

- Without an acceleration in homebuilding, a slowdown in population growth, or both, Canada’s housing affordability crisis will likely persist.

Austin Thompson

Education

Schools should focus on falling math and reading grades—not environmental activism

From the Fraser Institute

In 2019 Toronto District School Board (TDSB) trustees passed a “climate emergency” resolution and promised to develop a climate action plan. Not only does the TDSB now have an entire department in their central office focused on this goal, but it also publishes an annual climate action report.

Imagine you were to ask a random group of Canadian parents to describe the primary mission of schools. Most parents would say something along the lines of ensuring that all students learn basic academic skills such as reading, writing and mathematics.

Fewer parents are likely to say that schools should focus on reducing their environmental footprints, push students to engage in environmental activism, or lobby for Canada to meet the 2016 Paris Agreement’s emission-reduction targets.

And yet, plenty of school boards across Canada are doing exactly that. For example, the Seven Oaks School Division in Winnipeg is currently conducting a comprehensive audit of its environmental footprint and intends to develop a climate action plan to reduce its footprint. Not only does Seven Oaks have a senior administrator assigned to this responsibility, but each of its 28 schools has a designated climate action leader.

Other school boards have gone even further. In 2019 Toronto District School Board (TDSB) trustees passed a “climate emergency” resolution and promised to develop a climate action plan. Not only does the TDSB now have an entire department in their central office focused on this goal, but it also publishes an annual climate action report. The most recent report is 58 pages long and covers everything from promoting electric school buses to encouraging schools to gain EcoSchools certification.

Not to be outdone, the Vancouver School District (VSD) recently published its Environmental Sustainability Plan, which highlights the many green initiatives in its schools. This plan states that the VSD should be the “greenest, most sustainable school district in North America.”

Some trustees want to go even further. Earlier this year, the British Columbia School Trustees Association released its Climate Action Working Group report that calls on all B.C. school districts to “prioritize climate change mitigation and adopt sustainable, impactful strategies.” It also says that taking climate action must be a “core part” of school board governance in every one of these districts.

Apparently, many trustees and school board administrators think that engaging in climate action is more important than providing students with a solid academic education. This is an unfortunate example of misplaced priorities.

There’s an old saying that when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority. Organizations have finite resources and can only do a limited number of things. When schools focus on carbon footprint audits, climate action plans and EcoSchools certification, they invariably spend less time on the nuts and bolts of academic instruction.

This might be less of a concern if the academic basics were already understood by students. But they aren’t. According to the most recent data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the math skills of Ontario students declined by the equivalent of nearly two grade levels over the last 20 years while reading skills went down by about half a grade level. The downward trajectory was even sharper in B.C., with a more than two grade level decline in math skills and a full grade level decline in reading skills.

If any school board wants to declare an emergency, it should declare an academic emergency and then take concrete steps to rectify it. The core mandate of school boards must be the education of their students.

For starters, school boards should promote instructional methods that improve student academic achievement. This includes using phonics to teach reading, requiring all students to memorize basic math facts such as the times table, and encouraging teachers to immerse students in a knowledge-rich learning environment.

School boards should also crack down on student violence and enforce strict behaviour codes. Instead of kicking police officers out of schools for ideological reasons, school boards should establish productive partnerships with the police. No significant learning will take place in a school where students and teachers are unsafe.

Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with school boards ensuring that their buildings are energy efficient or teachers encouraging students to take care of the environment. The problem arises when trustees, administrators and teachers lose sight of their primary mission. In the end, schools should focus on academics, not environmental activism.

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoCOVID virus, vaccines are driving explosion in cancer, billionaire scientist tells Tucker Carlson

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoIs HNIC Ready For The Winnipeg Jets To Be Canada’s Heroes?

-

Dr. Robert Malone2 days ago

Dr. Robert Malone2 days agoThe West Texas Measles Outbreak as a Societal and Political Mirror

-

illegal immigration1 day ago

illegal immigration1 day agoDespite court rulings, the Trump Administration shows no interest in helping Abrego Garcia return to the U.S.

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoHorrific and Deadly Effects of Antidepressants

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis warns Canadian voters of Liberal plan to penalize religious charities

-

Education1 day ago

Education1 day agoSchools should focus on falling math and reading grades—not environmental activism

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHousing starts unchanged since 1970s, while Canadian population growth has more than tripled