Alberta

ASIRT clears two Edmonton Police officers in death of suspect in custody

From the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT)

EPS officers acted reasonably in fatality

On Aug. 18, 2016, the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT) was directed to investigate the circumstances surrounding an encounter with the Edmonton Police Service (EPS), resulting in the death of a 34-year-old man that same day in Edmonton, Alberta.

As the death occurred during an encounter with police, the man’s death was deemed to be an in-custody death, and the investigation was assigned to ASIRT.

At 8:50 p.m. on that day, EPS received a call from Alberta Hospital regarding the man, who was a resident of Alberta Hospital with a history of violence and weapons offences. The man had been released from the hospital on a pass but was not complying with his conditions and failed to return to the hospital. A warrant was issued for his arrest. EPS was advised that the man was at a family residence causing a disturbance and was believed to be intoxicated by some form of drug, “freaking out,” and sweating profusely. The man was not described as being violent, but there was concern that he may become violent.

Two EPS officers responded to the residence, which was an apartment on the 14th floor. As the officers entered the suite, they immediately spoke with the man in an attempt to calm him. The man was initially compliant, but then attempted to exit onto the balcony and appeared to throw an object over the railing. Given his intoxication and behaviour, it was determined that permitting him onto the balcony was unsafe. As a result, when he failed to comply with verbal directions, the officers tried to take him into custody. Officers told the man that he was under arrest, and each officer tried to take control of one of the man’s arms. The man immediately became aggressive and resisted, and was ultimately taken to the ground by the two officers, where he continued to struggle against being placed into handcuffs. No blows were delivered. A wrist-lock, used as a pain-compliance technique, had no impact on the man. Following a struggle, the man was fully restrained and still able to speak.

The officers notified dispatch that the man was in custody and requested the assistance of Emergency Medical Services (EMS). At this point, the man was breathing and responsive, but was described as pale and sweaty. Prior to the arrival of EMS, the man’s condition deteriorated, and he exhibited difficulty breathing and failed to respond to verbal commands. One of the officers contacted dispatch to request that EMS be expedited, while members removed the restraints and placed the man in the recovery position. While awaiting EMS, the man stopped breathing. Officers alternated performing chest compressions on the man until EMS arrived. EMS transported the man to the University of Alberta Hospital where he was pronounced dead.

A small plastic bag of methamphetamine was recovered from the man’s person, along with a bottle containing 40 yellow pills of unknown origin.

The cause of death was attributed to “excited delirium syndrome secondary to methamphetamine toxicity.” The struggle with police and subsequent restraint was noted as a contributing factor. A toxicology report confirmed the presence of methamphetamine and its metabolites, as well as a small amount of oxycodone.

The man had been staying in a hotel room since leaving Alberta Hospital, and a search of that room revealed few personal effects but clear evidence of drug use, including methamphetamine as well as used and unused syringes. The room was in complete disarray with clothing on the floor and syringes throughout the room.

Under S.25 of the Criminal Code, a police officer is permitted to use as much force as is reasonably necessary in the lawful execution of their duties. Given the fact that they had been called to the residence for assistance and the fact that there was an outstanding warrant for the arrest of the man, the officers had both the lawful ability and duty to arrest him, and were permitted to use reasonably necessary force to do so.

When the man’s behaviour escalated, some use of force was necessary both to ensure the safety of the man, but also to detain him. To allow a mentally ill and intoxicated man access to the balcony would have been both irresponsible and highly dangerous. The force used by the two officers was brief, and was used only for the purpose of gaining control of the man, who had become non-compliant and was physically resistant. No weapons were used by the officers, and the use of force ceased immediately upon the man being restrained. Once the man was restrained and when a concern emerged regarding the man’s physical condition, police called EMS, removed the restraints, and attempted first aid.

While police and medical efforts were unfortunately unsuccessful in saving the life of the man, there is no basis to suggest any degree of negligence in failing to care for the man while in medical distress, and the force used to arrest him was no more than was reasonably necessary in the circumstances.

Having reviewed the matter, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that either officer committed any Criminal Code offence while dealing with the man. While his death was tragic, the actions of the officers were not only reasonable and lawful in the circumstances, they were necessary. A failure to take custody of the man would have left him in a position where he presented a serious risk to himself, the family members who were present, and the officers.

This was a terrible event for all involved. Notwithstanding his mental health and drug issues, the man had a family who loved him and wanted him to be safe and well. The officers attended with the intention of providing assistance to both the man and his family, to ensure everyone’s safety, and to have the man returned to Alberta Hospital so he could be properly treated. The outcome was one that no one present wanted and is an example of a situation when officers attempt to do everything correctly but there is still a tragic outcome. ASIRT extends its most sincere condolences to the family of the man.

Alberta

Alberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail, Mackenzie Moir and Lauren Asaad

In October, Alberta’s provincial government announced forthcoming legislative changes that will allow patients to pay out-of-pocket for any diagnostic test they want, and without a physician referral. The policy, according to the Smith government, is designed to help improve the availability of preventative care and increase testing capacity by attracting additional private sector investment in diagnostic technology and facilities.

Unsurprisingly, the policy has attracted Ottawa’s attention, with discussions now taking place around the details of the proposed changes and whether this proposal is deemed to be in line with the Canada Health Act (CHA) and the federal government’s interpretations. A determination that it is not, will have both political consequences by being labeled “non-compliant” and financial consequences for the province through reductions to its Canada Health Transfer (CHT) in coming years.

This raises an interesting question: While the ultimate decision rests with Ottawa, does the Smith government’s new policy comply with the literal text of the CHA and the revised rules released in written federal interpretations?

According to the CHA, when a patient pays out of pocket for a medically necessary and insured physician or hospital (including diagnostic procedures) service, the federal health minister shall reduce the CHT on a dollar-for-dollar basis matching the amount charged to patients. In 2018, Ottawa introduced the Diagnostic Services Policy (DSP), which clarified that the insured status of a diagnostic service does not change when it’s offered inside a private clinic as opposed to a hospital. As a result, any levying of patient charges for medically necessary diagnostic tests are considered a violation of the CHA.

Ottawa has been no slouch in wielding this new policy, deducting some $76.5 million from transfers to seven provinces in 2023 and another $72.4 million in 2024. Deductions for Alberta, based on Health Canada’s estimates of patient charges, totaled some $34 million over those two years.

Alberta has been paid back some of those dollars under the new Reimbursement Program introduced in 2018, which created a pathway for provinces to be paid back some or all of the transfers previously withheld on a dollar-for-dollar basis by Ottawa for CHA infractions. The Reimbursement Program requires provinces to resolve the circumstances which led to patient charges for medically necessary services, including filing a Reimbursement Action Plan for doing so developed in concert with Health Canada. In total, Alberta was reimbursed $20.5 million after Health Canada determined the provincial government had “successfully” implemented elements of its approved plan.

Perhaps in response to the risk of further deductions, or taking a lesson from the Reimbursement Action Plan accepted by Health Canada, the province has gone out of its way to make clear that these new privately funded scans will be self-referred, that any patient paying for tests privately will be reimbursed if that test reveals a serious or life-threatening condition, and that physician referred tests will continue to be provided within the public system and be given priority in both public and private facilities.

Indeed, the provincial government has stated they do not expect to lose additional federal health care transfers under this new policy, based on their success in arguing back previous deductions.

This is where language matters: Health Canada in their latest CHA annual report specifically states the “medical necessity” of any diagnostic test is “determined when a patient receives a referral or requisition from a medical practitioner.” According to the logic of Ottawa’s own stated policy, an unreferred test should, in theory, be no longer considered one that is medically necessary or needs to be insured and thus could be paid for privately.

It would appear then that allowing private purchase of services not referred by physicians does pass the written standard for CHA compliance, including compliance with the latest federal interpretation for diagnostic services.

But of course, there is no actual certainty here. The federal government of the day maintains sole and final authority for interpretation of the CHA and is free to revise and adjust interpretations at any time it sees fit in response to provincial health policy innovations. So while the letter of the CHA appears to have been met, there is still a very real possibility that Alberta will be found to have violated the Act and its interpretations regardless.

In the end, no one really knows with any certainty if a policy change will be deemed by Ottawa to run afoul of the CHA. On the one hand, the provincial government seems to have set the rules around private purchase deliberately and narrowly to avoid a clear violation of federal requirements as they are currently written. On the other hand, Health Canada’s attention has been aroused and they are now “engaging” with officials from Alberta to “better understand” the new policy, leaving open the possibility that the rules of the game may change once again. And even then, a decision that the policy is permissible today is not permanent and can be reversed by the federal government tomorrow if its interpretive whims shift again.

The sad reality of the provincial-federal health-care relationship in Canada is that it has no fixed rules. Indeed, it may be pointless to ask whether a policy will be CHA compliant before Ottawa decides whether or not it is. But it can be said, at least for now, that the Smith government’s new privately paid diagnostic testing policy appears to have met the currently written standard for CHA compliance.

Lauren Asaad

Policy Analyst, Fraser Institute

Alberta

Housing in Calgary and Edmonton remains expensive but more affordable than other cities

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Austin Thompson

In cities across the country, modest homes have become unaffordable for typical families. Calgary and Edmonton have not been immune to this trend, but they’ve weathered it better than most—largely by making it easier to build homes.

Specifically, faster permit approvals, lower municipal fees and fewer restrictions on homebuilders have helped both cities maintain an affordability edge in an era of runaway prices. To preserve that edge, they must stick with—and strengthen—their pro-growth approach.

First, the bad news. Buying a home remains a formidable challenge for many families in Calgary and Edmonton.

For example, in 2023 (the latest year of available data), a typical family earning the local median after-tax income—$73,420 in Calgary and $70,650 in Edmonton—had to save the equivalent of 17.5 months of income in Calgary ($107,300) or 12.5 months in Edmonton ($73,820) for a 20 per cent down payment on a typical home (single-detached house, semi-detached unit or condominium).

Even after managing such a substantial down payment, the financial strain would continue. Mortgage payments on the remaining 80 per cent of the home’s price would have required a large—and financially risky—share of the family’s after-tax income: 45.1 per cent in Calgary (about $2,757 per month) and 32.2 per cent in Edmonton (about $1,897 per month).

Clearly, unless the typical family already owns property or receives help from family, buying a typical home is extremely challenging. And yet, housing in Calgary and Edmonton remains far more affordable than in most other Canadian cities.

In 2023, out of 36 major Canadian cities, Edmonton and Calgary ranked 8th and 14th, respectively, for housing affordability (relative to the median after-tax family income). That’s a marked improvement from a decade earlier in 2014 when Edmonton ranked 20th and Calgary ranked 30th. And from 2014 to 2023, Edmonton was one of only four Canadian cities where median after-tax family income grew faster than the price of a typical home (in Calgary, home prices rose faster than incomes but by much less than in most Canadian cities). As a result, in 2023 typical homes in Edmonton cost about half as much (again, relative to the local median after-tax family income) as in mid-sized cities such as Windsor and Kelowna—and roughly one-third as much as in Toronto and Vancouver.

To be clear, much of Calgary and Edmonton’s improved rank in affordability is due to other cities becoming less and less affordable. Indeed, mortgage payments (as a share of local after-tax median income) also increased since 2014 in both Calgary and Edmonton.

But the relative success of Alberta’s two largest cities shows what’s possible when you prioritize homebuilding. Their approach—lower municipal fees, faster permit approvals and fewer building restrictions—has made it easier to build homes and helped contain costs for homebuyers. In fact, homebuilding has been accelerating in Calgary and Edmonton, in contrast to a sharp contraction in Vancouver and Toronto. That’s a boon to Albertans who’ve been spared the worst excesses of the national housing crisis. It’s also a demographic and economic boost for the province as residents from across Canada move to Alberta to take advantage of the housing market—in stark contrast to the experience of British Columbia and Ontario, which are hemorrhaging residents.

Alberta’s big cities have shown that when governments let homebuilders build, families benefit. To keep that advantage, policymakers in Calgary and Edmonton must stay the course.

-

Automotive13 hours ago

Automotive13 hours agoPoliticians should be honest about environmental pros and cons of electric vehicles

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Hits the Brakes on Population

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘Almost Sounds Made Up’: Jeffrey Epstein Was Bill Clinton Plus-One At Moroccan King’s Wedding, Per Report

-

Crime2 days ago

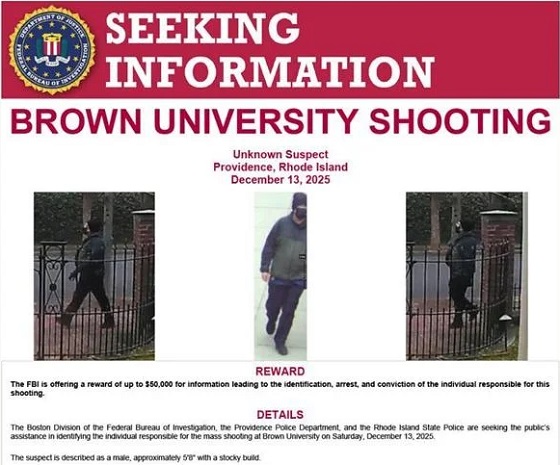

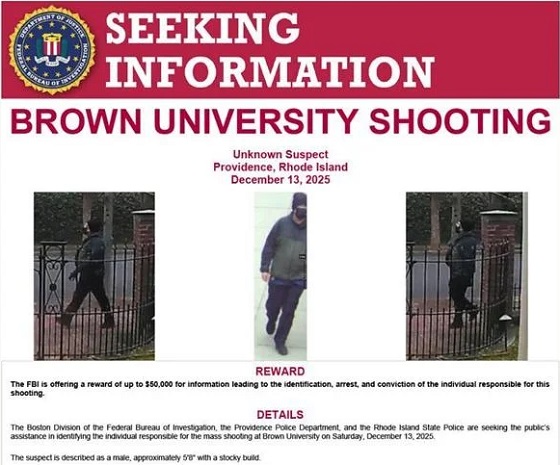

Crime2 days agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours agoHunting Poilievre Covers For Upcoming Demographic Collapse After Boomers

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump signs order reclassifying marijuana as Schedule III drug

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoHousing in Calgary and Edmonton remains expensive but more affordable than other cities