David Clinton

Are We Winning the Patient-to-Doctor Ratio War?

The fact that millions of Canadians lack primary healthcare providers is a big deal. The grand promise of universal healthcare rings hollow for families forced to spend six hours waiting in a hospital emergency room for a simple ear infection diagnosis.

Just how big a deal is it? Statistics Canada data from 2021 ranks provinces by their ability to provide primary health providers. As you can see from the chart, New Brunswick and Ontario were doing the best, with doctors for nearly 90 percent of their residents. Quebec, able to find providers for just 78.4 percent of their population, landed at the bottom. But even just 10-15 percent without proper coverage is a serious systemic failure.

Since healthcare is administered by the provinces, it makes sense to assume that provincial policies will influence results. So comparing access to primary care practice results over time might help us understand what’s working and what isn’t.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To that end, I pulled Statistics Canada data tracking total employment in offices of physicians (NAICS code 621111) by province. The data covers all employees (including nurses, office managers, and receptionists) in all non-hospital medical offices providing services that don’t include mental health.

I originally searched unsuccessfully for usable data specific to doctors. But as it turns out, such data would have included surgeons and other hospital-based specialties when I’m really looking for general (family) care providers. So I think what we got will actually act as a better proxy for primary care access.

Do keep in mind that staffing levels in the sector represent just one of many statistical signals we could use to understand the healthcare universe. And it’s just a proxy that’s not necessarily a perfect map to reality.

In any case, I adjusted the numbers by provincial populations so they’d make statistical sense. The chart below contains ratios representing how many residents there are per worker between 2010 and 2023:

You might notice that PEI is missing from that chart. That’s because the reported numbers fell below Statistics Canada’s privacy threshold for most of the covered years.

Alberta, with a ratio of just 282:1 is the current champion, while Newfoundland (438:1) has the worst record. But changes over time are where things get interesting. BC’s performance declined by more than 11 percent. And Quebec improved by more than 40 percent!

As you can see for yourself in that chart, Quebec’s most dramatic growth took place between 2016 and 2019. What was going on around that time? Well, both Bill 10 and Bill 20 were introduced in 2015.

- Bill 10 restructured the healthcare system by reducing the number of administrative regions and centralizing governance to streamline services and improve efficiency.

- Bill 20 established patient quotas for doctors, mandating a minimum number of patients they were required to see. Physicians who did not meet these quotas faced penalties, such as reduced compensation.

I don’t need to speak French to assume that those measures must have inspired an awful lot of anger and push back from within the medical profession. But the results speak for themselves.

Or do they? You see there’s something else about Quebec we can’t ignore: Chaoulli v. Quebec (2005). That’s the Supreme Court of Canada case where the Canada Health Act’s ban on private delivery of healthcare was ruled unconstitutional (for Quebec, at any rate).

As a direct result of that decision, there are now more than 50 procedures that can be performed in private surgical clinics in the province. The number of private clinics nearly doubled between 2014 and 2023.

Predictably, wait times for surgeries fell significantly over that time. But the numbers of non-hospital employees would probably have climbed at the same rate. That could possibly go further to explain Quebec’s steady and consistent improvements in our data.

What about the other provinces? There have been structural changes to delivery policies in recent years, but they’re mostly too new to have produced a measurable impact. But here’s a brief overview of what’s being tried:

- This Toronto Star piece describes efforts in both Ontario and BC involving plans among some smaller municipalities to build and manage family health practices and pay their doctors as employees. The idea is that many doctors will prefer to avoid the headaches of starting and running their own businesses and would prefer instead to work for someone else. The obvious goal is to attract new doctors to underserved communities. It’s still way too soon to know whether they’ll be successful in the desperate race for the shrinking pool of family physicians.

- Both Ontario and Alberta have championed Family Health Groups (FHGs), where physicians receive additional incentives for providing comprehensive care. Ontario’s Family Health Networks (FHN) and Family Health Organizations (FHO) also compensate physicians based on the number and demographics of enrolled patients.

- British Columbia and Nova Scotia have implemented variations of a Longitudinal Family Physician (LFP) Payment Model. LFPs compensate family physicians based on factors like time spent with patients, patient panel size, and the complexity of care. They claim to promote team-based, patient-partnered care.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Business

Why Does Canada “Lead” the World in Funding Racist Indoctrination?

Artificial Intelligence

When A.I. Investments Make (No) Sense

Based mostly on their 2024 budget, the federal government has promised $2.4 billion in support of artificial intelligence (A.I.) innovation and research. Given the potential importance of the A.I. sector and the universal expectation that modern governments should support private business development, this doesn’t sound all that crazy.

But does this particular implementation of that role actually make sense? After all, the global A.I. industry is currently suffering existential convulsions, with hundreds of billions of dollars worth of sector dominance regularly shifting back and forth between the big corporate players. And I’m not sure any major provider has yet built a demonstrably profitable model. Is Canada in a realistic position to compete on this playing field and, if we are, should we really want to?

First of all, it’s worth examining the planned spending itself.

- $2 billion over five years was committed to the Canadian Sovereign A.I. Compute Strategy, which targets public and private infrastructure for increasing A.I. compute capacity, including public supercomputing facilities.

- $200 million has been earmarked for the Regional Artificial Intelligence Initiative (RAII) via Regional Development Agencies intended to boost A.I. startups.

- $100 million to boost productivity is going to the National Research Council Canada’s A.I. Assist Program

- The Canadian A.I. Safety Institute will receive $50 million

In their goals, the $300 million going to those RAII and NRC programs don’t seem substantially different from existing industry support programs like SR&ED. So there’s really nothing much to say about them.

And I wish the poor folk at the Canadian A.I. Safety Institute the best of luck. Their goals might (or might not) be laudable, but I personally don’t see any chance they’ll be successful. Once A.I. models come on line, it’s only a matter of time before users will figure out how to make them do whatever they want.

But I’m really interested in that $2 billion for infrastructure and compute capacity. The first red flag here has to be our access to sufficient power generation.

Canada currently generates more electrical power than we need, but that’s changing fast. To increase capacity to meet government EV mandates, decarbonization goals, and population growth could require doubling our capacity. And that’s before we try to bring A.I. super computers online. Just for context, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Oracle all have plans to build their own nuclear reactors to power their data centers. These things require an enormous amount of power.

I’m not sure I see a path to success here. Plowing money into A.I. compute infrastructure while promoting zero emissions policies that’ll ensure your infrastructure can never be powered isn’t smart.

However, the larger problem here may be the current state of the A.I. industry itself. All the frantic scrambling we’re seeing among investors and governments desperate to buy into the current gold rush is mostly focused on the astronomical investment returns that are possible.

There’s nothing wrong with that in principle. But “astronomical investment returns” are also possible by betting on extreme long shots at the race track or shorting equity positions in the Big Five Canadian banks. Not every “possible” investment is appropriate for government policymakers.

Right now the big players (OpenAI, Anthropic, etc.) are struggling to turn a profit. Sure, they regularly manage to build new models that drop the cost of an inference token by ten times. But those new models consume ten or a hundred times more tokens responding to each request. And flat-rate monthly customers regularly increase the volume and complexity of their requests. At this point, there’s apparently no easy way out of this trap.

Since business customers and power users – the most profitable parts of the market – insist on using only the newest and most powerful models while resisting pay-as-you-go contracts, profit margins aren’t scaling. Reportedly, OpenAI is betting on commoditizing its chat services and making its money from advertising. But it’s also working to drive Anthropic and the others out of business by competing head-to-head for the enterprise API business with low prices.

In other words, this is a highly volatile and competitive industry where it’s nearly impossible to visualize what success might even look like with confidence.

Is A.I. potentially world-changing? Yes it is. Could building A.I. compute infrastructure make some investors wildly wealthy? Yes it could. But is it the kind of gamble that’s suitable for public funds?

Perhaps not.

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

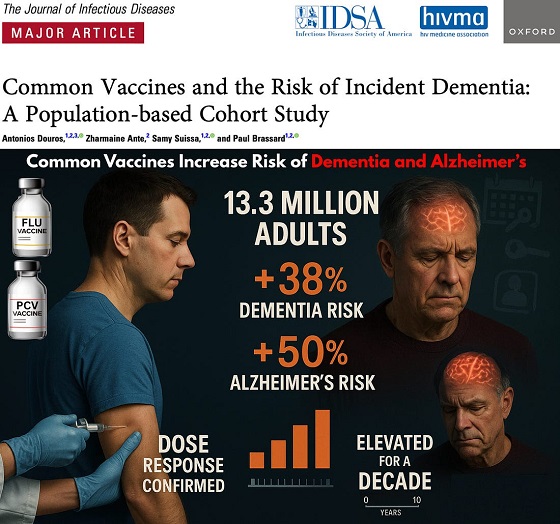

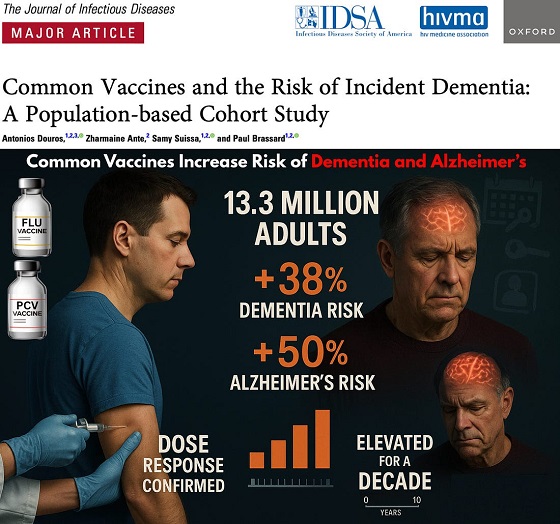

Focal Points1 day ago

Focal Points1 day agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s

-

Automotive24 hours ago

Automotive24 hours agoThe $50 Billion Question: EVs Never Delivered What Ottawa Promised

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoThe Data That Doesn’t Exist

-

Economy2 days ago

Economy2 days agoAffordable housing out of reach everywhere in Canada

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoStorm clouds of uncertainty as BC courts deal another blow to industry and investment

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoThe Climate-Risk Industrial Complex and the Manufactured Insurance Crisis

By

By