Christopher Rufo

America’s Verdict

What the Daniel Penny acquittal means for America

A New York City courtroom Monday issued a stunning verdict: Daniel Penny, a veteran US marine who restrained a threatening homeless subway rider named Jordan Neely, who later died in police custody, is not guilty of negligent homicide. And the verdict was not just about Penny. Make no mistake: the Black Lives Matter era of “restorative justice” is over and the real spirit of justice is returning to America.

Penny’s trial captured public attention because it dramatically emblematized this critical cultural faultline. Most immediately, it symbolized a recurrent theme in New York City about the failures of law enforcement, and the appropriate response to criminality. But it was also a story that the Left sought to turn into a racial morality play by repeating the BLM playbook they applied to the death of George Floyd, to Trayvon Martin, to Michael Brown and countless others.

In this story, Daniel Penny (“the white man” in the loaded description of the prosecutor Dafna Yoran) was a racist white man, who cruelly hunted down and killed an innocent black man (a “Micheal Jackson impersonator”) who was peacefully riding the subway. In this telling, neither man is an individual; rather, each is a symbol of a system of racist white supremacy, organized around enacting violence on black bodies, for no reason, in the United States, and across the world.

The first imperative of restorative justice is to recognize this crucial ideological context; a point which Penny’s hyper-ideological prosecutor Dafna Yoran made explicit in a widely circulated video in which she boasted of reducing a felony murder charge in a previous trial to a manslaughter charge because she “felt sorry” for the trauma which the African-American killer had endured.

Daniel Penny, naturally, received no such considerations. In his case, the restorative task was to scapegoat “the white man” in the service of advancing a radical pro-crime agenda, consistent with defunding the police and turning the US criminal justice system into a politically organized system of justice comparable to the two-tier justice system that now exists in the UK.

This was a task that was pursued both inside and outside the courtroom. As with the trial of Derek Chauvin in Minneapolis following the death of George Floyd, professional activists were mobilized to protest on the street outside the trial with the intention to manipulate proceedings: witnesses reported that the shouting of the activists were audible inside the courtroom. But this time, the jury did not surrender to pressure.

Jordan Neely was, in fact, like George Floyd: both were violent criminals with a long record of antisocial behavioral problems who suffered from drug problems, and eventually died under troubling circumstances. But Derek Chauvin’s jury failed in its duty to separate the facts from ideological myths, and failed to stand up to political pressure. Chauvin was convicted by a jury frightened into complicity, and effectively thrown to the mob.

By contrast, in New York Monday, another conception of justice prevailed. Despite the activists ringing the courtroom, a hostile media chumming the waters, and a highly irregular legal procedure which saw the prosecution withdrawing one of Penny’s charges on Friday in order to avoid a mistrial and seek conviction on a lesser charge, the jurors retained their composure, and stuck to the facts and the law. Whatever fear they may have felt, they overcame it, and Penny was correctly found not guilty.

What will happen next? My own suspicion is that the verdict will not generate anything like the violence, riots, and disorder that followed the death of George Floyd. Americans are finished with the failed regime of the Left. The past four years have clarified what “social justice” really means and exhausted all remaining patience for granting activists the benefit of the doubt. The extraordinary shamelessness of Jordan Neely’s father in launching a civil suit against Penny over the death of a son he didn’t raise exemplifies the moral emptiness that was formerly, by many, mistaken for social justice.

In reality, “social justice” was never about justice: it was about the political subversion of justice to achieve pathological and ideological ends. The contrast with Penny himself could not be more striking. Penny is not merely not guilty, he is an unambiguous hero, who correctly understood and carried out his duty, with great courage, in a dangerous situation. He believed that it was his duty to use his training to protect women and children from a violent individual with a previous record of subway assault, and he was right to do so.

Today’s verdict marks the end of an era. BLM, which seemed unstoppable four years ago, is finished. Its activists are discredited, and its grip on the public imagination is broken. No doubt the violent spirit of the movement will seek to resurface in the future, but a brutal and stupid decade of moral and judicial corruption has come to a close.

With its passing, the opportunity returns to truly confront the problems that have plagued American cities for a generation. Penny’s heroism should never have been necessary because Jordan Neely should never have been riding that train. Neely himself was failed by BLM and the ideology of social justice, just as Penny was persecuted by it: it was also social justice which, from misguided ideas of compassion, stopped Neely from getting the treatment he needed.

The correct moral attitude, as well as the right social policy, is to dismantle this system entirely—in academia and media, where it generates its alibis, but above all in criminal justice. That means holding the attorneys responsible for this shameful prosecution accountable, returning to the system of “broken windows” policing that made New York under Giuliani the safest big city in America—and extending that system across the rest of the United States.

This article has been provided free of charge but it takes a lot of effort to produce journalism of this quality. We are grateful for those who consider supporting these important journalistic efforts. Thank you for considering a free or paid subscription.

This article was originally published in IM—1776.

Christopher Rufo

The “No Kings” Protest Is Pure Fantasy

Christopher F. Rufo

Christopher F. Rufo

The underlying theory is that Donald Trump is an authoritarian leader on the cusp of becoming king.

I spent Father’s Day weekend in Hood River, Oregon, and stumbled upon the local “No Kings” anti-Trump protest. The crowd was populated mostly by Baby Boomers, who appeared to be living out a political fantasy, in which they could “stop fascism” by reenacting the protest movements of their youth. One sign, typical of the genre, derided Trump as a “felon, rapist, con man”; another riffed on Mary Poppins, reading “super callous, fragile, racist, sexist, Nazi POTUS.”

The underlying theory of this protest, which reportedly drew upward of 5 million demonstrators nationwide, is that Donald Trump is an authoritarian leader on the cusp of becoming king. The only way to stop him is to flood the streets and persuade the American people that Trump is a rotten character with despotic ambitions.

The theory, of course, is nonsense. Trump is a duly elected president. He is working with Congress on the budget. His deportation policy, which lent momentum to the weekend’s demonstrations, is predicated on enforcing existing law. Though President Trump contested the results of his first reelection campaign, he ultimately relented and peacefully transferred power to President Joe Biden—hardly the behavior of a tyrant.

Yet the protests are not without utility for the Left. They are not intended to grapple with the reality of the Trump presidency but to submerge reality in fantasy. The first step in entrenching the Left’s fictions in the public mind is to cultivate a sense of hysteria. In the president’s first term, crowds wore vagina-shaped hats and marched in the bitter cold. The tone of the “No Kings” protest was no less absurd, with women in Handmaid’s Tale costumes warning that Trump would reduce them to sex slaves.

The next step is to turn public energy into a threat. As seen in Los Angeles earlier this month, the Left’s more aggressive factions can operate alongside “mostly peaceful protests,” aiming to provoke law enforcement into overreacting. During Trump’s first term, leftist activists often played a double game—promoting “nonviolent” demonstrations for women’s rights or racial justice while allowing more confrontational elements to intimidate Trump supporters.

This time, immigration is the flash point. Trump has tied his presidency to mass deportations. The Left believes it can stop him by carefully shaping public opinion. That means highlighting emotional—if sometimes misleading—stories of deportation victims and sympathetic portrayals of protesters clashing with National Guard troops. These narratives are designed to paint Trump as an authoritarian and the Left as the resistance, with the aim of driving his approval ratings low enough to weaken his presidency.

The irony is that Trump does not have the power of a king—or, arguably, even the full power of the presidency, as established in Article II of the Constitution. District courts have blocked many of his policies down to the most minute detail, sometimes within hours of their adoption. A federal judge even prohibited the administration from removing gender-related content from government websites.

At the Hood River protest, I noticed a generational divide. The Baby Boomers were the most gullible, engaging in 1960s protest nostalgia and genuinely believing that America was under threat of incipient fascism. The younger generation, which came to political consciousness during the Trump era, seemed more skeptical. At the edge of the protest, I saw a group of teenage boys holding signs that read “Ban Onions” and “Ban Scratchy Blankets.” They seemed to see through the fiction of “No Kings,” viewing left-wing Baby Boomers, rather than Trump, as the rightful targets of satire and rebellion.

I hope that this attitude prevails. For 60 years, the Boomers have held a grip on the American political narrative; it has not been a story that conduced to national well-being. America elected Trump, in part, to demolish the remaining fantasies of the 1968 generation. Yes, no kings—and no more lies.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Business

Washington Got the Better of Elon Musk

The tech tycoon’s Department of Government Efficiency was prevented from achieving its full reform agenda.

It seems that the postmodern world is a conspiracy against great men. Bureaucracy now favors the firm over the founder, and the culture views those who accumulate too much power with suspicion. The twentieth century taught us to fear such men rather than admire them.

Elon Musk—who has revolutionized payments, automobiles, robotics, rockets, communications, and artificial intelligence—may be the closest thing we have to a “great man” today. He is the nearest analogue to the robber barons of the last century or the space barons of science fiction. Yet even our most accomplished entrepreneur appears no match for the managerial bureaucracy of the American state.

Musk will step down from his position leading the Department of Government Efficiency at the end of May. At the outset, the tech tycoon was ebullient, promising that DOGE would reduce the budget deficit by $2 trillion, modernize Washington, and curb waste, fraud, and abuse. His marketing plan consisted of memes and social media posts. Indeed, the DOGE brand itself was an ironic blend of memes, Bitcoin, and Internet humor.

Three months later, however, Musk is chastened. Though DOGE succeeded in dismantling USAID, modernizing the federal retirement system, and improving the Treasury Department’s payment security, the initiative as a whole has fallen short. Savings, even by DOGE’s fallible math, will be closer to $100 billion than $2 trillion. Washington is marginally more efficient today than it was before DOGE began, but the department failed to overcome the general tendency of governmental inertia.

Musk’s marketing strategy ran into difficulties, too. His Internet-inflected language was too strange for the average citizen. And the Left, as it always does, countered proposed cuts with sob stories and personal narratives, paired with a coordinated character-assassination attempt portraying Musk as a greedy billionaire eager to eliminate essential services and children’s cancer research.

However meretricious these attacks were, they worked. Musk’s popularity has declined rapidly, and the terror campaign against Tesla drew blood: the company’s stock has slumped in 2025—down around 20 percent—and the board has demanded that Musk return to the helm.

But the deeper problem is that DOGE has always been a confused effort. It promised to cut the federal budget by roughly a third; deliver technocratic improvements to make government efficient; and eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse. As I warned last year, no viable path existed for DOGE to implement these reforms. Further, these promises distracted from what should have been the department’s primary purpose: an ideological purge.

Ironically, this was the one area where DOGE made major progress. In just a few months, the department managed to dismantle one of the most progressive federal agencies, USAID; defund left-wing NGOs, including cutting over $1 billion in grants from the Department of Education; and advance a theory of executive power that enabled the president to slash Washington’s DEI bureaucracy.

Musk also correctly identified the two keys to the kingdom: human resources and payments. DOGE terminated the employment of President Trump’s ideological opponents within the federal workforce and halted payments to the most corrupted institutions, setting the precedent for Trump to withhold funds from the Ivy League universities. At its best, DOGE functioned as a method of targeted de-wokification that forced some activist elements of the Left into recession—a much-needed program, though not exactly what was originally promised.

Ultimately, DOGE succeeded where it could and failed where it could not. Musk’s project expanded presidential power but did not fundamentally change the budget, which still requires congressional approval. Washington’s fiscal crisis is not, at its core, an efficiency problem; it’s a political one. When DOGE was first announced, many Republican congressmen cheered Musk on, declaring, “It’s time for DOGE!” But this was little more than an abdication of responsibility, shifting the burden—and ultimately the blame—onto Musk for Congress’s ongoing failure to take on the politically unpopular task of controlling spending.

With Musk heading back to his companies, it remains to be seen who, if anyone, will take up the mantle of budget reform in Congress. Unfortunately, the most likely outcome is that Republicans will revert to old habits: promising to balance the budget during campaign season and blowing it up as soon as the legislature convenes.

The end of Musk’s tenure at DOGE reminds us that Washington can get the best even of great men. The fight for fiscal restraint is not over, but the illusion that it can be won through efficiency and memes has been dispelled. Our fate lies in the hands of Congress—and that should make Americans pessimistic.

Subscribe to Christopher F. Rufo.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoBefore Trudeau average annual immigration was 617,800. Under Trudeau number skyrocketted to 1.4 million annually

-

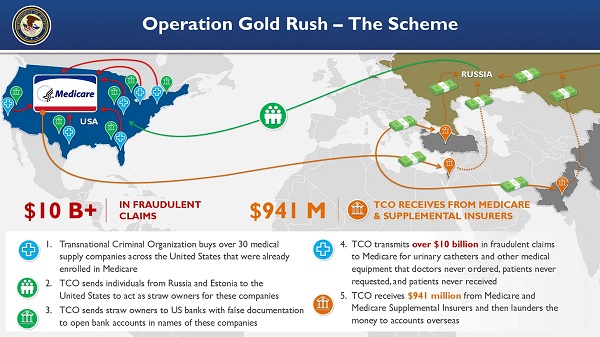

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days ago“This is a total fucking disaster”

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘I Know How These People Operate’: Fmr CIA Officer Calls BS On FBI’s New Epstein Intel

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoCanada’s euthanasia regime is already killing the disabled. It’s about to get worse

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoBlackouts Coming If America Continues With Biden-Era Green Frenzy, Trump Admin Warns

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day agoNew Book Warns The Decline In Marriage Comes At A High Cost

-

Red Deer2 days ago

Red Deer2 days agoJoin SPARC in spreading kindness by July 14th

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoPrime minister can make good on campaign promise by reforming Canada Health Act