National

Alexandra Mendès becomes first Liberal MP to publicly call on Trudeau to resign

From LifeSiteNews

The House of Commons assistant deputy speaker said he has heard from multiple constituents that the current prime minister is no longer the right man for the job.

A Liberal MP who serves as the assistant deputy speaker of the House of Commons has become the first in the party to publicly call for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to resign, saying directly that he is not the “right leader” for the party.

The call for Trudeau to step down came from Liberal MP Alexandra Mendès, who is from Quebec’s Brossard-St. Lambert riding. In an interview with Radio Canada on Monday, Mendès said directly, “My constituents do not see Mr. Trudeau as the person who should carry the Party into the next election and that’s the message that I carry.”

“I didn’t hear from two, three people. I heard it from dozens and dozens of people. He is no longer the right leader,” she said.

Mendès said that as she listens to her constituents, which is what “supposedly what we’re meant to do,” then “yes, I have to say we would have to change leadership.”

The Trudeau resignation call comes amid dismal polling numbers for Trudeau as well as losing support from the socialist New Democratic Party (NDP) to keep him in power. NDP leader Jagmeet Singh pulled his official support for Trudeau’s Liberals last week.

Late last month, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre called on Singh to pull his support for Trudeau’s Liberals in order for an election to be held.

Recent polls show that the Conservatives under Poilievre would win a majority government in a landslide were an election held today. Singh’s NDP and Trudeau’s Liberals would lose a massive number of seats.

As for Trudeau, his woes continue to mount. LifeSiteNews recently reported how the national elections campaign director for Canada’s federal Liberal Party announced he was stepping down because, according to sources close to the party, he does not think Trudeau can with a fourth consecutive election.

2025 Federal Election

Allegations of ethical misconduct by the Prime Minister and Government of Canada during the current federal election campaign

Preston Manning

Preston Manning

A letter to the Ethics Commissioner sent April 9th, 2025

On April 4, 2025, during the current federal election period, in which employees of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) report on all aspects of the election, the unelected Prime Minister, without any consultation with or authorization by parliament but apparently with the concurrence of the Minister of Heritage, promised an increase of $150 million in the budget of the CBC on top of its $1.38 billion budget for the current fiscal year.

The CBC consistently and for obvious reasons tends to share the ideological orientation of the governing Liberal Party and its political allies, and supports many of their policy positions. It tends to ignore or oppose those of the Conservative Official Opposition which proposes dismantling the CBC.

The unelected Liberal Prime Minister promising a $150 million bonus to the CBC in the middle of an election campaign would thus strike any objective observer as unethical, damaging to public confidence in our democratic institutions, and deserving of investigation and commentary by your office.

In particular, it is respectfully requested that you address the following questions:

1. Has the Prime Minister acted unethically by promising the state owned broadcasting corporation, sympathetic to the governing party, a $150 million increase in its budget, during a federal election campaign?

2. Is the promise of a $150 million increase in the budget of the CBC, during an election period in which the CBC is expected to give objective coverage to the campaign, in effect a defacto bribe and contrary to the spirit and the letter of the Conflict of Interest Code and Act?

In addition, on April 7, 2025, again during the current election period, the Prime Minister has announced that the federal government will distribute approximately $4 billion in carbon rebate payments directly to approximately 13 million Canadians, many of whom are eligible voters, and will do so prior to the election day of April 28.

This naturally raises the following questions which it is again respectfully requested that you address:

3. Has the Prime Minister and the federal government acted unethically by authorizing the distribution, prior to election day, of almost $4 billion in rebate payments to approximately 13 million Canadians, many of whom are voters, and doing so with the suspected intent of winning the support of those voters?

4. Is the promise and delivery, prior to election day, of almost $4 billion in rebate payments to approximately 13 million Canadians, many of whom are voters, in effect a defacto attempt to bribe those voters with their own money, and contrary to the spirit and the letter of the Conflict of Interest Code and Act?

To assist in the consideration of these allegations, suppose the UN were to ask Canada to supervise a national election in a third world country where democracy is frail and elections subject to abuse by those in authority. Suppose further that the unelected president of that country, during the election campaign period, endeavored to secure:

· The support of the state broadcasting corporation by promising it a huge increase in its budget, and,

· The support of millions of voters by ensuring that they received a generous personal payment from his government just prior to election day.

In such a situation, would not the Canadian monitoring authority be obliged to strongly censure such behaviors and report to the UN that such behavior calls into question the democratic legitimacy of the election subjected to such abuses?

If we as Canadians would consider such political behaviors anti-democratic and unacceptable if practiced in a foreign country, ought we not to come to the same conclusion even more quickly and certainly when they are regrettably practiced in our own?

Please respond to questions 1-4 above prior to April 25, 2025 and please ensure that your responses are made public prior to that date.

Thanking you for your service and your commitment to safeguarding public confidence in Canada’s democratic institutions and processes.

Your sincerely,

Preston Manning PC CC AOE

2025 Federal Election

BREAKING from THE BUREAU: Pro-Beijing Group That Pushed Erin O’Toole’s Exit Warns Chinese Canadians to “Vote Carefully”

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

As polls tighten in Canada’s high-stakes federal election—one increasingly defined by reports of Chinese state interference—a controversial Toronto diaspora group tied to past efforts to topple former Conservative leader Erin O’Toole has resurfaced, decrying what it calls a disregard for favoured Chinese Canadian voices in candidate selection.

At a press conference in Markham yesterday, the Chinese Canadian Conservative Association (CCCA) accused both the Liberal and Conservative parties of bypassing diaspora input and “directly appointing candidates without consulting community groups or even party members.”

In what reads as a carefully coded message to the Chinese diaspora across Canada, Mandarin-language reports covering the event stated that the group “stressed at the media meeting that people should think rationally and vote carefully,” and urged “all Chinese people to actively participate and vote for the candidate they approve of—rather than the party.”

The CCCA’s latest press conference—surprising in both tone and timing—came just weeks after political pressure forced the resignation of Liberal MP Paul Chiang, following reports that he had allegedly threatened his Conservative opponent, Joseph Tay—now the party’s candidate in Don Valley North—and suggested to Chinese-language journalists that Tay could be handed over to the Toronto consulate for a bounty.

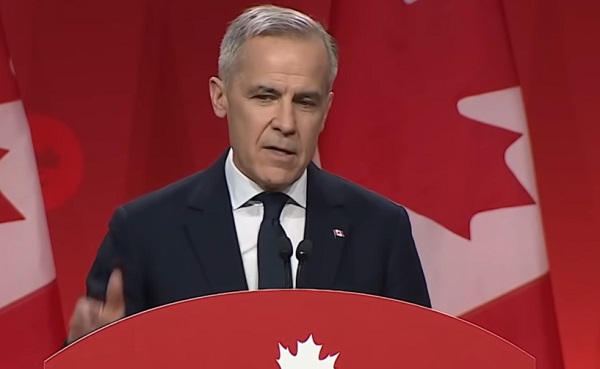

Chiang, who had been backed by Prime Minister Mark Carney, stepped down amid growing concern from international NGOs and an RCMP review.

One of the CCCA’s leading voices is a Markham city councillor who campaigned for Paul Chiang in 2021 against the Conservatives, and later sought the Conservative nomination in Markham against Joseph Tay. While the group claims to represent Conservative-aligned diaspora interests, public records and media coverage show that it backed Paul Chiang again in 2025 and is currently campaigning for Shaun Chen, the Liberal candidate in the adjacent Scarborough North riding.

The Toronto Sun reported today that new polling by Leger for Postmedia shows Mark Carney’s Liberals polling at 47 percent in the Greater Toronto Area—just three points ahead of Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives at 44 percent. In most Canadian elections, this densely populated region proves decisive in determining who forms government in Ottawa.

In a statement that appeared to subtly align with Beijing’s strategic messaging, the group warned voters:

“At today’s press conference, we called on all Canadian voters: please think rationally and vote carefully. Do not support parties or candidates that attempt to divide society, launch attacks or undermine important international relations, especially against countries such as India and China that have important global influence.”

In a 2024 review of foreign interference, the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) warned that nomination contests in Canada remain highly vulnerable to manipulation by state-backed diaspora networks, particularly those run by Chinese and Indian diplomats.

The report found that these networks have “directed or influenced Canadian political candidates,” with efforts targeting riding-level nominations seen as a strategic entry point for foreign influence.

The Chinese Canadian Conservative Association first attracted national attention in the wake of the 2021 federal election, when it held a press conference blaming then-Conservative leader Erin O’Toole’s “anti-China rhetoric” for the party’s poor showing in ridings with large Chinese Canadian populations.

At that event, CCCA’s lead spokesperson—a York Region councillor and three-time former Conservative candidate—openly defended Beijing’s position on Taiwan and Canada’s diplomatic crisis over the “two Michaels,” claiming China’s detention of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor only occurred because “Canada started the war.”

The councillor also criticized Canada’s condemnation of China’s human rights abuses, saying such statements “alienate Chinese voters.”

The group’s views—repeatedly echoed in Chinese-language media outlets close to the PRC—resonate with talking points promoted by the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, a political influence operation run by Beijing that seeks to mobilize ethnic Chinese communities abroad in support of Party objectives.

Shortly after denouncing O’Toole’s China policy, the CCCA publicly endorsed Brampton Mayor Patrick Brown to replace him—a candidate known for cultivating strong relationships with United Front-linked groups. Brown gave a speech in 2022 at an event co-organized by the Confederation of Toronto Chinese Canadian Organizations (CTCCO)—a group repeatedly cited in Canadian national security reporting for its alignment with PRC political messaging and its close working relationship with the Chinese consulate in Toronto.

CTCCO also maintains ties with Peter Yuen, a former Toronto Police Deputy Chief who was selected as Mark Carney’s Liberal candidate in the riding of Markham–Unionville. As first revealed by The Bureau, Yuen joined a 2015 Ontario delegation to Beijing to attend a massive military parade hosted by President Xi Jinping and the People’s Liberation Army, commemorating the CCP’s victory over Japan in the Second World War. The delegation included senior CTCCO leaders and Ontario political figures who, in 2017, helped advocate for the establishment of Nanjing Massacre Memorial Day and a monument in Toronto—a movement widely promoted by the Chinese consulate and supported by figures from CTCCO and the Chinese Freemasons of Toronto, both of which have been cited in United Front reporting.

Yuen also performed in 2017 at diaspora events affiliated with the United Front Work Department, standing beside CTCCO leader Wei Cheng Yi while singing a patriotic song about his dedication to China—as the Chinese Consul General looked on.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoRCMP Whistleblowers Accuse Members of Mark Carney’s Inner Circle of Security Breaches and Surveillance

-

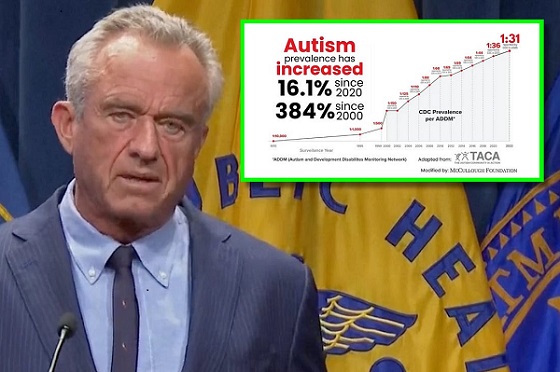

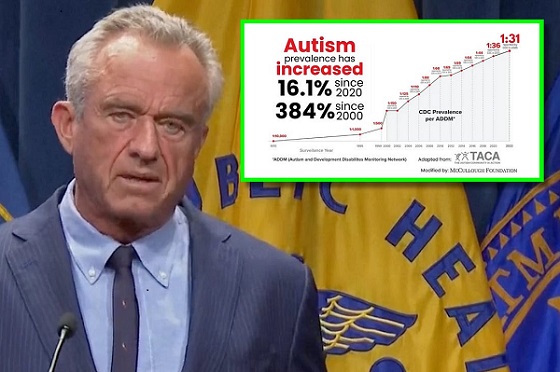

Autism2 days ago

Autism2 days agoAutism Rates Reach Unprecedented Highs: 1 in 12 Boys at Age 4 in California, 1 in 31 Nationally

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoTrump admin directs NIH to study ‘regret and detransition’ after chemical, surgical gender transitioning

-

Also Interesting1 day ago

Also Interesting1 day agoBetFury Review: Is It the Best Crypto Casino?

-

Autism1 day ago

Autism1 day agoRFK Jr. Exposes a Chilling New Autism Reality

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoCanadian student denied religious exemption for COVID jab takes tech school to court

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoBureau Exclusive: Chinese Election Interference Network Tied to Senate Breach Investigation

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoUK Supreme Court rules ‘woman’ means biological female