Addictions

Alberta closing Red Deer’s only overdose prevention site in favor of recovery model

Alberta’s Minister of Mental Health and Addiction, Dan Williams, at the Alberta Legislature in Edmonton on Sept. 11 2024. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Alberta’s Minister of Mental Health and Addiction explains the shift from overdose prevention to recovery amid community concerns

On Sept. 23, Alberta announced the city of Red Deer would be closing the community’s only overdose prevention site by spring 2025. The closure will mark the first time an Alberta community completely eliminates its supervised consumption services.

The decision to close the site was taken by the city — not the province. But it aligns with Alberta’s decision to prioritize recovery-focused approaches to addiction and mental health over harm-reduction strategies.

“The whole idea of the Alberta Recovery Model is that unless you create off-ramps [from] addiction, you’re barreling ahead towards a brick wall, and that’s going to be devastating,” Alberta Minister of Mental Health and Addiction Dan Williams told Canadian Affairs in an interview in September.

However, the closure — which parallels similar moves by other provinces — has sparked debate over whether recovery-oriented models adequately meet the needs of at-risk populations.

The Alberta Recovery Model

The Alberta Recovery Model, which was first introduced by Alberta’s UCP government in November 2023, emphasizes prevention, early intervention, treatment and recovery.

It is informed by recommendations from Alberta’s Mental Health and Addiction Advisory Council and research from the Stanford Lancet Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis.

“Alberta, in our continuum of care, has everything from low entry, low barriers, and zero cost [for] detox, to treatment, to virtual opioid dependency, to outreach teams working with shelters,” said Williams.

Williams said that Alberta intends to continue funding safe consumption sites as short-term harm-reduction measures. But it views them as temporary components in the continuum of care.

This is not without controversy.

At the Feb. 15 Red Deer council meeting where councillors voted 5-2 to close the city’s safe consumption site, some councillors noted that safe consumption sites play an essential role in the continuum of care.

“Each individual is at a different stage of addiction … the overdose prevention site does play a role in the treatment spectrum,” said Coun. Dianne Wyntjes, who voted against the closure.

While Red Deer is home to Alberta’s first provincially funded addiction treatment facility, Wyntjes noted there had been reports within the community of the facility lacking capacity to meet demand.

She pointed to Lethbridge’s experience in 2020, where overdose deaths spiked after its consumption site was replaced with mobile services.

The Ontario government’s recent decision to close 10 safe consumption sites located near schools and daycares has prompted similar concerns.

In August, Ontario Health Minister Sylvia Jones told reporters that the province plans to “very quickly” replace the closed sites with Homelessness and Addiction Recovery Treatment (HART) hubs that prioritize community safety, treatment and recovery. But critics — including site workers, NDP MPPs and harm-reduction advocates — have warned these shutdowns will lead to an increase in fatal overdoses.

It is possible that Alberta, Ontario and other jurisdictions will make other moves in tandem in the coming months and years.

In April, Alberta announced it was partnering with Ontario and Saskatchewan to build recovery-focused care systems. The partnerships include sharing of best practices and advocating for recovery-focused policies and investments at the federal level.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

‘Mandatory treatment’

Another controversial component of Alberta — and other provinces’ — recovery-oriented strategy is involuntary care.

The UCP government has said it plans to introduce “compassionate intervention” legislation next year that will enable family members, doctors or police officers to seek court orders mandating treatment for individuals with substance use disorders who pose a risk to themselves or others.

“If someone is a danger to themselves or others in the most extreme circumstances because of their addiction, then we as a society have an obligation to intervene, and that might include mandatory treatment,” said Williams.

Critics have raised concerns about increasing reliance on involuntary care options.

“Over the last two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in reliance on involuntary services [such as psychiatric admissions and treatment orders], while voluntary services have not kept up with demand,” the B.C. division of the Canadian Mental Health Association said in a Sept. 18 statement published on their website.

The statement followed an announcement by B.C. Premier David Eby — who was recently reelected — to expand involuntary care in that province.

Research from Yale University’s School of Public Health indicates involuntary interventions for substance use are generally no more effective than voluntary treatment, and can in some cases cause more harm than good. The research notes that “involuntary centers often serve as venues for abuse.”

A 2023 McMaster University study that synthesized the research on involuntary treatment from international jurisdictions similarly found inconclusive outcomes. It recommended expanding voluntary care options to minimize reliance on involuntary measures.

Williams emphasized that the province’s involuntary care legislation would target “a very small group of people for whom all else has failed … those at the far end of the addiction spectrum with very serious and devastating addictions.”

‘Off-ramps from addiction’

Over the past six years, Alberta has incrementally increased its mental health and addiction budget from an initial $50 million to a cumulative total of $1.5 billion.

The funding boost has enabled Alberta to eliminate a $40 daily user fee for some detox and recovery services, add 10,000 publicly funded addiction treatment spaces, and expand access to its Virtual Opioid Dependency Program, which offers same-day access to life-saving medications.

To support addiction prevention, Williams said Alberta is expanding CASA Classrooms in schools. These offer mental health support and therapy to Grade 4-12 students who have ongoing mental health challenges, and equip school staff and caregivers to support these students.

“Mental health and addiction needs to be as connected to the emergency room as it is to the classroom,” Williams said. “We need to be able to understand low-acuity chronic mental health challenges as they begin to manifest [in the community].”

The province is also in the process of establishing 11 residential recovery communities across the province. These centres provide free, extended treatment averaging four months — which is longer than most recovery programs.

Oct. 23 marked the one-year anniversary of one such centre, the Lethbridge Recovery Community. The $19-million, 50-bed facility served more than 110 clients in its first year and expects to serve about 200 individuals in 2025.

“I’m coming to see that entering treatment is only the start,” said Sean P., a client of Lethbridge Recovery Community, in a government press release celebrating the anniversary.

“With the support of the staff and the community here, I’m beginning to face my past and make real changes. Recovery is giving me the tools I need for this journey, and I’m genuinely excited to keep growing and moving forward with their help.”

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

2025 Federal Election

Poilievre to invest in recovery, cut off federal funding for opioids and defund drug dens

From Conservative Party Communications

Poilievre will Make Recovery a Reality for 50,000 Canadians

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pledged he will bring the hope that our vulnerable Canadians need by expanding drug recovery programs, creating 50,000 new opportunities for Canadians seeking freedom from addiction. At the same time, he will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and ensure that any remaining sites do not operate within 500 meters of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks and seniors’ homes, and comply with strict new oversight rules that focus on pathways to treatment.

More than 50,000 people have lost their lives to fentanyl since 2015—more Canadians than died in the Second World War. Poilievre pledged to open a path to recovery while cracking down on the radical Liberal experiment with free access to illegal drugs that has made the crisis worse and brought disorder to local communities.

Specifically, Poilievre will:

- Fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians. A new Conservative government will fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians in treatment centres with a proven record of success at getting people off drugs. This includes successful models like the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre, which helps people recover and reunite with their families, communities, and culture. To ensure the best outcomes, funding will follow results. Where spaces in good treatment programs exist, we will use them, and where they need to expand, these funds will allow that.

- Ban drug dens from being located within 500 metres of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks, and seniors’ homes and impose strict new oversight rules. Poilievre also pledged to crack down on the Liberals’ reckless experiments with free access to illegal drugs that allow provinces to operate drug sites with no oversight, while pausing any new federal exemptions until evidence justifies they support recovery. Existing federal sites will be required to operate away from residential communities and places where families and children frequent and will now also have to focus on connecting users with treatment, meet stricter regulatory standards or be shut down. He will also end the exemption for fly-by-night provincially-regulated sites.

“After the Lost Liberal Decade, Canada’s addiction crisis has spiralled out of control,” said Poilievre. “Families have been torn apart while children have to witness open drug use and walk through dangerous encampments to get to school. Canadians deserve better than the endless Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death.”

Since the Liberals were first elected in 2015, our once-safe communities have become sordid and disordered, while more and more Canadians have been lost to the dangerous drugs the Liberals have flooded into our streets. In British Columbia, where the Liberals decriminalized dangerous drugs like fentanyl and meth, drug overdose deaths increased by 200 percent.

The Liberals also pursued a radical experiment of taxpayer-funded hard drugs, which are often diverted and resold to children and other vulnerable Canadians. The Vancouver Police Department has said that roughly half of all hydromorphone seizures were diverted from this hard drugs program, while the Waterloo Regional Police Service and Niagara Regional Police Service said that hydromorphone seizures had exploded by 1,090% and 1,577%, respectively.

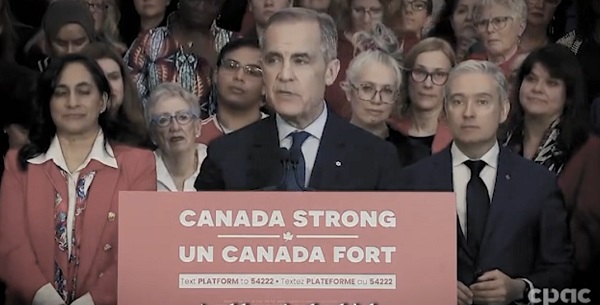

Despite the death and despair that is now common on our streets, bizarrely Mark Carney told a room of Liberal supporters that 50,000 fentanyl deaths in Canada is not “a crisis.” He also hand-picked a Liberal candidate who said the Liberals “would be smart to lean into drug decriminalization” and another who said “legalizing all drugs would be good for Canada.”

Carney’s star candidate Gregor Robertson, an early advocate of decriminalization and so-called safe supply, wanted drug dens imposed on communities without any consultation or public safety considerations. During his disastrous tenure as Vancouver Mayor, overdoses increased by 600%.

Alberta has pioneered an approach that offers real hope by adopting a recovery-focused model of care, leading to a nearly 40 percent reduction in drug-poisoning deaths since 2023—three times the decrease seen in British Columbia. However, we must also end the Liberal drug policies that have worsened the crisis and harmed countless lives and families.

To fund this policy, a Conservative government will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and sue the opioid manufacturers and consulting companies who created this crisis in the first place.

“Canadians deserve better than the Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death,” said Poilievre. “We will treat addiction with compassion and accountability—not with more taxpayer-funded poison. We will turn hurt into hope by shutting down drug dens, restoring order in our communities, funding real recovery, and bringing our loved ones home drug-free.”

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoProvince to expand services provided by Alberta Sheriffs: New policing option for municipalities

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCSIS Warned Beijing Would Brand Conservatives as Trumpian. Now Carney’s Campaign Is Doing It.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoIs HNIC Ready For The Winnipeg Jets To Be Canada’s Heroes?

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoMade in Alberta! Province makes it easier to support local products with Buy Local program

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoNo Matter The Winner – My Canada Is Gone

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoHorrific and Deadly Effects of Antidepressants

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCampaign 2025 : The Liberal Costed Platform – Taxpayer Funded Fiction

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoA Perfect Storm of Corruption, Foreign Interference, and National Security Failures