Addictions

Alberta and opioids III: You can’t always just stop

Monty Ghosh at Highlevel Diner, May 30. Photo: Paul Wells

By Paul Wells

This is the concluding installment in a series on drugs in Alberta. Previously:

i. “Worse Than I’ve Ever Seen,” June 4

ii. “Alberta’s System Builder,” June 7

To support ambitious reporting on important issues, please consider a paid subscription:

A matter of expectations

Street family

My tour guide for much of my visit to Edmonton was Dr. Monty Ghosh, a clinician who’s on faculty at the University of Calgary and the University of Edmonton. He seems to talk to everybody who works with substance users in Alberta, from his own patients to front-line clinicians to the Alberta government. His relations with the latter go up and down, but he urged me to talk to Marshall Smith, the chief of staff to premier Danielle Smith.

On my first night in Edmonton Ghosh walked me around a neighbourhood that included the George Spady Society supervised-consumption site, the Hope Mission’s Herb Jamieson Centre, and the Royal Alexandra Hospital, which has a supervised-consumption service on its premises.

A lot of people use the services these places provide. Other people don’t. Shelters in particular are tricky: they’re usually for single people who arrive alone. “The Hope, the Herb, the Navigation Centre, offering the world,” one Edmonton Police Service officer told me. “But all these places have one thing in common: rules.” If you have a spouse or a pet, you want to keep your drug supply or you want to stay close to your “street family” — the community spirit in neighbourhoods like this is striking, and might be surprising to people who prefer to stay away — a shelter’s probably not for you.

Several of the places we visited weren’t ready to welcome us when we showed up unannounced. To say the least, they’re busy. That was the case at Radius Community Health and Healing, an institutional building in a more residential part of the neighbourhood. Radius is a drop-in clinic and, as we’ll see, quite a bit more.

On a sunny weekday afternoon, more than a dozen people stood, sat or lay on the building’s front steps and truncated lawn. One lay on his back, shirtless, not moving visibly. Ghosh asked the man whether he was all right, asked again, finally nudged him. The man stirred, looked around. Ghosh apologized mildly for bothering him, then checked in on two other people who also weren’t moving. They turned out to be all right too.

Francesco Mosaico, Radius’s medical director, was on his way home for the day when we arrived, but we made plans to talk the next day. When I returned, I met Mosaico and Radius’s executive director, Tricia Smith, in her office.

I think it’s important to hear them out, because when drug use becomes the object of political debate, it’s natural to talk as though policy decisions are the main thing keeping people from getting well. This can lead to a lot of blame on one hand, and to excessive optimism on the other. In fact the biggest thing that keeps people from getting well is often the entire sum of their lives until now, compounded by the influence of drugs that are more potent than anything earlier generations had to deal with.

The most complex patients

Radius offers primary care to people “experiencing multiple barriers,” Smith said. That can include homelessness, addiction, severe mental health problems, criminal records. The centre’s team includes 12 family physicians and three psychiatrists. They currently see about 3,000 patients.

Radius has Western Canada’s only non-profit dental clinic. The centre runs a respite program for people who are not sick enough to be in acute care but are too sick to be managing independently on their own. It has a program for pregnant women experiencing homelessness. It runs on a harm-reduction model, so they don’t need to be drug-free to go into the program. It has an interdisciplinary Assertive Community Treatment team to help people with mental-health and substance problems find and stay in market apartments, with frequent assistance. There’s a supervised consumption site in the basement.

“In fact,” Smith said, “we actually have an exemption from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta to filter out and keep the most complex patients. The least complex, we refer elsewhere.” I couldn’t get care in Radius if I tried; they’d politely refer me elsewhere. They’re for the people who need the most help.

After my visit, Smith wrote to me to add another program to the list: Kindred House, which for more than 25 yearss has supported women and Trans women sex workers. “The women we see are from age 18 to 50, predominantly Indigenous, have intergenerational trauma, past/current trauma, substance use issues, often houseless or couch surfing,” Smith wrote.

Smith has been at Radius for three and a half years. While I was there, I asked her how work at Radius is going. “It’s going fabulously, honestly,” she said. She arrived early in the COVID pandemic, after eight years in Alberta government departments — which in turn followed 20 years as a Canadian Forces army nurse, including in combat zones. “I’m in the right place,” she said of Radius. “It felt like coming home.”

How come? “The staff, the team, the work, the dedication. It just feels like family. I missed that. Being in the military was a big thing. This work that this group does is just really amazing. The team is amazing and it’s hard, but it’s good work.”

And how’s the workload evolving? “Unfortunately, for this population, the struggles are only increasing, and the number of individuals that are experiencing those challenges is not getting less,” she said. “The workload isn’t going anywhere. It’s getting more difficult.”

Paul Wells is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“Especially in the last couple years, I don’t think things have ever been worse for the vulnerable population,” Mosaico, Radius’s medical director, added. The same housing crunch that has made homes less affordable for everyone has put thousands of the most vulnerable on the street. Results: more frequent frostbite or burns from lamps lit to keep from freezing. Body lice. Trauma from watching friends die. And to Mosaico’s astonishment, frequent shigella outbreaks.

“Shigella’s a bacteria that causes torrential bloody diarrhea. It can be treated with a single dose of antibiotics. But if you’re homeless and you don’t have a place to take care of yourself… 70 percent of the cases have had to be hospitalized in the last two years…. I mean, they’re talking about potentially calling it an endemic disease, and it’s a disease of destitution. You see it in refugee camps in developing countries, not in the capital of Alberta, you know?”

Ten thousand times deadlier

Radius also works closely with the Alberta government to integrate its services with the “recovery-oriented system of care” that I told you about last week. There are two Radius staffers working at the Integrated Care Centre the police set up to replace the old, passive holding cells for overnight detention. There are two more at the Navigation Centre, which steers people toward social and government services. If there’s an Alberta model, they’re part of it. So I was fascinated by the response when I asked my hosts the basic question that sent me to Alberta: Why are so many people dying?

“I think it’s the nature of the drugs,” Mosaico said. “You know, people used to overdose and die. But I’ve been here 17 years. I think in the first 10 or 11 years it wasn’t very common to hear about overdoses by opioids. Every once in a while you’d hear about it, but it wasn’t a daily thing. Whereas now with fentanyl and carfentanil, it’s really dangerous.”

Carfentanil is 10,000 times more potent than morphine, 100 times more than fentanyl. The Edmonton Police won’t return stolen cars they recover until they’ve scrubbed them thoroughly, because even trace amounts of these drugs are too dangerous. “We’re finding clients who use methamphetamines and swear up and down they’re not taking opioids,” Mosaico said. “And then we do urine tests and it’s there. We think their dealers are lacing methamphetamine with fentanyl because it increases the addiction.”

The other big thing on his mind, Mosaico said, is that any program to guide users into recovery will bump up against the fact that different people have often lived starkly different lives.

93% 4+

“I don’t know if you’re familiar with Adverse Childhood Experiences — the ACEs study,” Mosaico said. I was, barely, but I needed a refresher.

The original study began in 1985 in San Diego, under Vincent Felitti, who ran an obesity clinic, and Rob Anda from the Centres for Disease Control. (If you want to learn more about the study, this article and this speech on Youtube are good places to start.)

“They surveyed 17,000 people,” Mosaico said. “They found, you know, if people had developmental trauma — so, trauma between the ages of 0 and 18 — and there are 10 different forms of trauma that the study bore out as being detrimental. Things like physical, emotional, sexual abuse; physical, emotional neglect; substance use in the family; untreated mental illness in the family; separation from biological parents; maternal figure being treated violently; and a household member going to jail.

“If those things occurred, you would just tally up the number of types of trauma and you’d get a score out of 10. What they found was, if you scored four or greater, that there seem to be adverse health effects in adulthood. And it wasn’t just the presence of addictions or mental illness. It was lung disease, heart disease, liver disease, certain forms of cancer, diabetes, obesity.” This is almost folk wisdom today, but at the time, Felitti and Anda were amazed at the strength of the correlations between childhood trauma and adult physical and mental health.

The original test has been widely replicated, and it usually finds that the proportion of people in a sample who’ve had four or more adverse childhood experiences is about 12%. So something like every eighth person you meet had a really difficult childhood, and while you can’t predict for individuals from statistical trends, there’s a good chance they’re still living with the fallout.

The team at Radius surveyed a large sample of the population under their care. The prevalence of high-risk ACE scores was about 93 percent, compared to 12 in the general population,” Mosaico said.

“Harvard has a center on the developing child, which has pulled together a lot of the science that explains the neurobiological link between the adverse trauma and the adverse health effects. They talk about limitations in the development of executive function, of decision-making, emotional regulation. Impulse control is underdeveloped, neuroanatomically in the brain. And instead what over-develops is the fight-or-flight response.

“So you’re dealing with a population that, because of their experiences, isn’t the same as the general population . And then that’s compounded by the fact that a high percentage of those clients who have high ACE scores also have traumatic brain injuries from living rough on the street. They also have adult trauma that compounds the childhood trauma. They have [fetal alcohol spectrum disorder], which impairs executive function even further.

“I hear these success stories and I think they’re wonderful, when you hear about people who have a difficult life and then they straighten up. And then, you know, they go back to their jobs and their families and they become leaders in their communities. But this is a population which is over-represented in every aspect of society, negatively as it were. In the prisons and child family welfare services. In the health system, you know, prevalence of HIV, tuberculosis, Hepatitis C, STIs, all that.

“And you look at them and you think, even if they managed to wait, you know, six months to get into an addiction recovery bed, after waiting for weeks to get into detox and they go through the program, what do they go back to? Most of them had to drop out of school. They have criminal records, which makes it hard to get a job. They’re disconnected and estranged from their families. They haven’t learned social skills.

“I had a client who lived in dumpsters for two and a half years. The fact that he just stayed housed — on income support — for the rest of his life was a huge win, right? It was important for his dignity, his quality of life. It’s just a matter of adjusting your expectations of what might actually be realistic.”

Thank you for reading Paul Wells. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Dr. Larson writes

The idea for these stories goes back to February, when it first became clear to me that 2023 would be Alberta’s worst year for overdose fatalities. I asked the communications team at the University of Calgary for names of people to talk to. Many weeks went by, because sometimes it’s ridiculous how hard it is to extract myself from Ottawa routine. After I published the second article in this series, the one where Marshall Smith showed me all the stuff Alberta is building, I received an email from Dr. Bonnie R. Larson, who’s on faculty at the University of Calgary. She thought I should have talked to her, and she thought I was too credulous in reporting the Alberta government’s side. I asked if I could publish part of her email. Here it is.

What cannot be taken for granted is Mr. Smith’s view that his goals are different, somehow nobler, than those of us on the front line. Smith paints a picture that front line providers’ priorities are at odds with his own. His perspective is at once undemocratic, insulting, and arrogant, belittling those who are doing the hard work of keeping people alive every day.

I will not have Smith speak for me in his suggestion that front liners lack system knowledge and that is why we support harm reduction. This ignores the excellent evidence supporting harm reduction interventions at the population level. Smith seems to think he knows from whence I “enter this conversation”. If so, why does he not engage me and my expert colleagues? Where I “enter this conversation” is at 20 years of working with the affected community and 13 years of post-secondary education. The only reason I am what Smith likes to dismiss as a “radical harm reduction activist”, is because the UCP, immediately upon taking office, set out to destroy harm reduction in Alberta. Nobody would have ever needed to fight this soul-destroying battle in the first place if Smith hadn’t put Alberta squarely on its current path of destruction. Yes, we should hope for a better tomorrow but that doesn’t excuse ignoring the past and present.

I would ask you to think about several additional factors that your analysis appears to ignore, including who actually benefits, in power and wealth, from Smiths’ system of so-called care? DId you consider the other ways that the UCP policy direction is moving the entire publicly-funded system steadily towards profit? Gunn (McCullough Centre) was a wonderful non-profit facility that helped many of my patients find their way to recovery from substance use disorders. While I agree that people should not have to pay for treatment, the question remains: in whose pockets do those tax dollars ultimately land?

You report that Smith indicates that they are “monitoring” the entire system. Where is the data from that monitoring? They have had five years now to show some outcomes, but who am I, just a lowly street doctor, to ask for population data? What I do know is that if deaths begin to decline, it is because so many are already gone. You should ask to see the data about which Smith so proudly boasts.

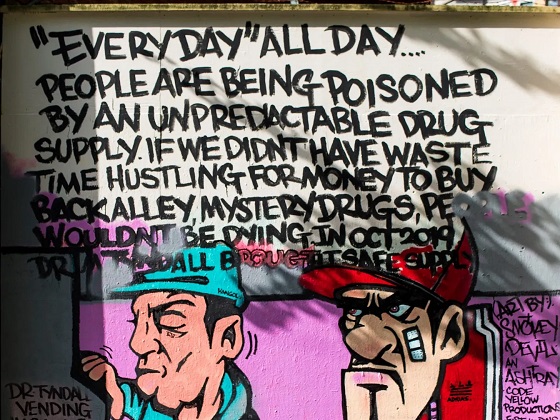

Smith’s entire premise that he is fixing the ‘addiction crisis’ is a fallacy. Addictions are not increasing. Deaths by drug poisonings are, however, and Smith’s circus is only making that worse. Allow me to spell it out for you: harm reduction addresses the drug poisoning crisis that is, no question, taking a horrific toll in Alberta and nationally. Smith’s ROSC, in contrast, addresses a figmentary addictions crisis.

One last tip. Medications used for opioid agonist treatment are not harm reduction, they are treatment. Nobody here is against treatment or recovery. But Marshall Smith is against harm reduction. Why can’t we just have the full spectrum of care??? Polarization is created by politicians to benefit politicians.

I don’t endorse everything Dr. Larson writes here. The data, or a lot of it, seems to me to be publicly available on the province’s impressive dashboard website. Use the tabs at the top of the page to navigate. And indeed, the story the dashboard tells is alarming, which, as I explained in this series’ first instalment, is why I flew west. But Larson’s years of front-line work has earned her, at the very least, a right of rebuttal.

Synthesis

On my last day in Edmonton, I met Monty Ghosh at Highlevel Diner, at the outer edge of the hip Strathcona neighbourhood on the south of the North Saskatchewan River. Highlevel is famous for its cinnamon buns, which, if I’m going to be honest, are noteworthy mostly for being large.

If the Alberta government and its most vociferous critics are thesis and antithesis, Ghosh tries to provide synthesis. He helped design the National Overdose Response Service, or NORS, which provides some of the emergency-response capability supervised consumption sites offer to people who aren’t near such a site or can’t use it for other reasons. He’s been critical of the Alberta government, but both sides keep lines of communication open.

I asked him about diverted safe supply — the idea that pharmaceutical opioids used in safe-supply programs in BC, principally hydromorphone tablets, are being sold or distributed away from their intended use. “I know it happens,” Ghosh said. “We sometimes get clients from British Columbia who come to Alberta to try to escape BC, because they’re looking for a fresh start. They’re looking for support and they’ll tell me themselves that they’ve diverted their safe supply.”

But what are the quantities? Trivial so far, Ghosh maintains. “Have I seen hydromorphone come into our province? Not at all, not yet.” This is the same thing I heard from Warren Driechel, the Edmonton deputy police chief.

Why do people divert their prescribed safe supply anyway? The answer Ghosh gave me was the answer I heard from everyone I asked. “They never used it. It just was not effective. The potency of the hydromorphone that they’re getting was nowhere near touching the fentanyl that they were using. It wasn’t dealing with the cravings, it wasn’t dealing with withdrawals, they felt it was useless. So what did they do? They sold it. They’re incredibly poor, they cannot afford their substance-use concerns and so therefore they supplement with revenue from hydromorphone.”

Before I flew to Edmonton, when Ghosh and I were trying to gauge on the phone what each of us thought of this infernal crisis, he figured out that I was interested in the differences between government policy in British Columbia and Alberta. “I’m not sure you want to hear this,” he said, “but I think it’s going to be bad everywhere.” I said that’s what I think too. Perhaps I surprised him.

I don’t know what happens next. Maybe things just stop getting worse everywhere on their own, for big complex reasons that resist easy analysis. Overdose deaths were lower last year in the United States, the capital of this hellscape, than the year before.

If not… well, we shall see. I wonder what happens in year six or seven of the effort the Alberta government is building. Is there resentment among people in ordinary hospitals and correctional facilities, who don’t have access to bespoke programs and personal attention? Does the ROSC system become bureaucratized after the first generation of administrators moves on?

Or does it start to win converts? David Eby, the NDP premier of British Columbia, has started putting distance between himself and his public-health advisors on legalization and safe supply. A new appointment in BC is being closely watched in Edmonton.

Or, conversely, does the Alberta recovery effort bump up against the limits imposed by the substances involved and by human nature? Reported recovery rates from addiction vary widely, depending in part on how you measure them. This paper puts the rate at less than 30%. If you even manage to double it, that still leaves a large cohort who aren’t getting better. Would their neighbours see them as people who “failed recovery” or “blew their chance?”

I won’t claim to know. I do hope that in the year ahead, more Canadians check their assumptions and stow their cheap certainties. Especially those who aspire to positions of leadership.

For the full experience subscribe to Paul Wells.

2025 Federal Election

Study links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

By Alexandra Keeler

A study links B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization to more opioid hospitalizations, but experts note its limitations

A new study says B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may have failed to reduce overdoses. Furthermore, the very policies designed to help drug users may have actually increased hospitalizations.

“Neither the safer opioid supply policy nor the decriminalization of drug possession appeared to mitigate the opioid crisis, and both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations,” the study says.

The study has sparked debate, with some pointing to it as proof that B.C.’s drug policies failed. Others have questioned the study’s methodology and conclusions.

“The question we want to know the answer to [but cannot] is how many opioid hospitalizations would have occurred had the policy not have been implemented,” said Michael Wallace, a biostatistician and associate professor at the University of Waterloo.

“We can never come up with truly definitive conclusions in cases such as this, no matter what data we have, short of being able to magically duplicate B.C.”

Jumping to conclusions

B.C.’s controversial safer supply policies provide drug users with prescription opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs. Its decriminalization policy permitted drug users to possess otherwise illegal substances for personal use.

The peer-reviewed study was led by health economist Hai Nguyen and conducted by researchers from Memorial University in Newfoundland, the University of Manitoba and Weill Cornell Medicine, a medical school in New York City. It was published in the medical journal JAMA Health Forum on March 21.

The researchers used a statistical method to create a “synthetic” comparison group, since there is no ideal control group. The researchers then compared B.C. to other provinces to assess the impact of certain drug policies.

Examining data from 2016 to 2023, the study links B.C.’s safer supply policies to a 33 per cent rise in opioid hospitalizations.

The study says the province’s decriminalization policies further drove up hospitalizations by 58 per cent.

“Neither the safer supply policy nor the subsequent decriminalization of drug possession appeared to alleviate the opioid crisis,” the study concludes. “Instead, both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations.”

The B.C. government rolled back decriminalization in April 2024 in response to widespread concerns over public drug use. This February, the province also officially acknowledged that diversion of safer supply drugs does occur.

The study did not conclusively determine whether the increase in hospital visits was due to diverted safer supply opioids, the toxic illicit supply, or other factors.

“There was insufficient evidence to conclusively attribute an increase in opioid overdose deaths to these policy changes,” the study says.

Nguyen’s team had published an earlier, 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine that also linked safer supply to increased hospitalizations. However, it failed to control for key confounders such as employment rates and naloxone access. Their 2025 study better accounts for these variables using the synthetic comparison group method.

The study’s authors did not respond to Canadian Affairs’ requests for comment.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Correlation vs. causation

Chris Perlman, a health data and addiction expert at the University of Waterloo, says more studies are needed.

He believes the findings are weak, as they show correlation but not causation.

“The study provides a small signal that the rates of hospitalization have changed, but I wouldn’t conclude that it can be solely attributed to the safer supply and decrim[inalization] policy decisions,” said Perlman.

He also noted the rise in hospitalizations doesn’t necessarily mean more overdoses. Rather, more people may be reaching hospitals in time for treatment.

“Given that the [overdose] rate may have gone down, I wonder if we’re simply seeing an effect where more persons survive an overdose and actually receive treatment in hospital where they would have died in the pre-policy time period,” he said.

The Nguyen study acknowledges this possibility.

“The observed increase in opioid hospitalizations, without a corresponding increase in opioid deaths, may reflect greater willingness to seek medical assistance because decriminalization could reduce the stigma associated with drug use,” it says.

“However, it is also possible that reduced stigma and removal of criminal penalties facilitated the diversion of safer opioids, contributing to increased hospitalizations.”

Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, is more critical.

“The [study’s] findings do not warrant the conclusion that these policies are causally associated with increased hospitalization or overdose,” said Urbanoski, who also holds the Canada Research Chair in Substance Use, Addictions and Health Services.

Her team published a study in November 2023 that measured safer supply’s impact on mortality and acute care visits. It found safer supply opioids did reduce overdose deaths.

Critics, however, raised concerns that her study misrepresented its underlying data and showed no statistically significant reduction in deaths after accounting for confounding factors.

The Nguyen study differs from Urbanoski’s. While Urbanoski’s team focused on individual-level outcomes, the Nguyen study analyzed broader, population-level effects, including diversion.

Wallace, the biostatistician, agrees more individual-level data could strengthen analysis, but does not believe it undermines the study’s conclusions. Wallace thinks the researchers did their best with the available data they had.

“We do not have a ‘copy’ of B.C. where the policies weren’t implemented to compare with,” said Wallace.

B.C.’s overdose rate of 775 per 100,000 is well above the national average of 533.

Elenore Sturko, a Conservative MLA for Surrey-Cloverdale, has been a vocal critic of B.C.’s decriminalization and safer supply policies.

“If the government doesn’t want to believe this study, well then I invite them to do a similar study,” she told reporters on March 27.

“Show us the evidence that they have failed to show us since 2020,” she added, referring to the year B.C. implemented safer supply.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoThe Federal Brief That Should Sink Carney

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

Media10 hours ago

Media10 hours agoCBC retracts false claims about residential schools after accusing Rebel News of ‘misinformation’

-

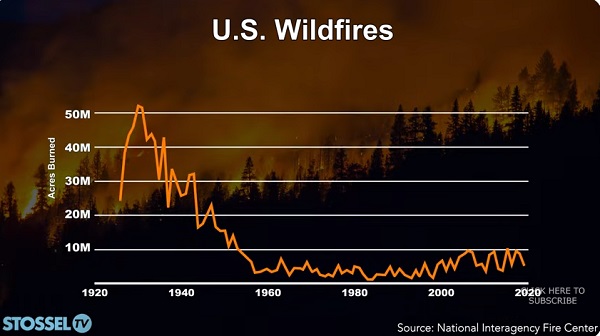

John Stossel1 day ago

John Stossel1 day agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoNearly Half of “COVID-19 Deaths” Were Not Due to COVID-19 – Scientific Reports Journal

-

Bjorn Lomborg9 hours ago

Bjorn Lomborg9 hours agoNet zero’s cost-benefit ratio is CRAZY high