Business

My European Favourites – Emilia-Romagna, Italy

My European Favourites – Emilia-Romagna, Italy

When people think of Italy, the first places that usually come to mind are Rome, Venice, Milan and the region of Tuscany, which includes Florence and Pisa. I would go to any of these places in a heartbeat. I love them all, but a region that many tourists overlook is Emilia-Romagna. The region’s name might not be well known, but its exceptional agricultural, automotive and mechanical sectors are known the world over.

Much of the gastronomy we associate with Italian cuisine has its roots in Emilia-Romagna. The region is famous for Parmigiano Reggiano (Parmesan cheese), Modena balsamic vinegar, Parma ham (prosciutto), and various types of pasta, just to name a few items. If you are a wine lover, Sangiovese and Lambrusco are two of their well-known “vinos” for their unique taste and quality.

If you are a motor sport buff, Ducati motorcycles and luxury car manufacturers Lamborghini, Maserati and Ferrari all have their roots in the area. With this racing heritage, it’s only natural that two major circuits are located in the region. The motorcycle racing Misano World Circuit Marco Simoncelli is located near Misano Adriatico and is named after a local rider who died during a race in Malaysia in 2011. The Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari located in Imola, which has been used for Formula 1 Grand Prix races, is named after Ferrari’s founder and his son. The track is sadly the location where three time World Champion Ayrton Senna of Brazil died in 1994.

It is best to do these tours with Parma as your base in Emilia-Romagna, but I enjoy its capital and largest city, Bologna. The city is Italy’s seventh largest with about 400,000 people, and it is famous for its medieval towers, churches, colonnades and historical city centre. The University of Bologna, which was established in 1088 AD, is the oldest university in the Western world. I love exploring the narrow city centre streets and browsing the food markets and shops with fresh produce, cured meats, fish, breads, pastas and regional products. I’m no chef, but I imagine that it would be sensory overload for any culinary expert. The small restaurants with street front patios make some of the best dishes you will eat in all of Italy. You have to go there.

Bologna’s medieval towers, a colonnade, a street full of restaurants and the Neptune Fountain.

Parmigiano Reggiano

We depart in the morning from our hotel in central Bologna to a family cheese making operation that produces the “king of cheeses,” Parmigiano Reggiano. The just over an hour drive brings us to a farm and factory near the town of Parma. They are members of the consortium that designates and controls authentic Parmigiano Reggiano production. Under law, the designation Parmigiano Reggiano is protected as a PDO (Protected Designations of Origin) and can be used only by certified producers from this area, so consumers know they have the real deal.

Around 1000 AD, monks reclaimed the marshy lands in the Po valley. The fertile land was plowed and worked by the monks using cows. With numerous cows, the monks had to invent a method to preserve the large quantities of high-quality milk they produced into a product that could be stored and used over time. The monks eventually developed a technique to produce a distinctive cheese in large boilers. The large round Parmigiano Reggiano is still made the same way today.

The Minardi family own and operate the Borgo del Gazzano farm factory that we are visiting. As an organic farm, they pay close attention to the entire local supply chain process to ensure the highest quality of ingredients. We arrive as they are reaching their final steps of the boiler process that was perfected by the monks long ago. Two men collect the curd from the boiler using muslin cloth and place it in large round molds. The cheese is left to set for a day or two then the mold will be removed to add a plastic wrap that has the imprint of the famous Parmigiano Reggiano stamp along with the date and the producer’s number. The mold is then reattached over the plastic wrap and tightened. The imprint from the wrap will solidify as a permanent mark on the rind over the next day. The wrap and mold are then removed and the cheese is placed in a rectangular vessel filled with a brine mixture for 20-25 days so that the cheese can absorb salt.

Production boilers, collecting the curd, the cheese freshly set in a mold and the brine bath.

Finally, the cheese is placed on a shelf in the warehouse to age for 12 months. Prepare to be astounded to see row after row of these shelves that are over 20 cheeses high and at least 80 cheeses long per side. It feels like a library made of cheese! Do you hear a mechanical sound coming from the next aisle? It is a machine working its way up, down and across the shelves. Its job is to grab one heavy cheese off the shelf at a time, spin it around so it can brush off the excess bits, flip the cheese, then place it safely back on the shelf, before automatically moving on to the next one. I guess now we know where they get the parmesan cheese shavings for the cheese shakers we buy at our local grocery store.

We will step outside to the barn area to see the cows and dairy operation before moving to the tasting area and shop. Tasting the celebrated “fromaggio,” with its distinctive texture and sharp flavour, at the very place where it is produced is really something special. This is not to be mistaken with the cheese we often get at home, as outside of Europe, companies can only use the word “Parmesan” to describe their cheese. To get the real deal, you have to make sure that it is clearly sold as, or even better, see it stamped as Parmigiano Reggiano.

Parmigiano shelves, the stamp on the rind, the cleaning machine and me with Alfonso Minardi.

Parma Ham (Prosciutto)

Just 30 minutes from the Borgo del Gazzano is a producer that makes another iconic food. The Lanfranchi family are specialists in the making of a cured meat known the world over as Raw Parma Ham (Prosciutto Crudo di Parma). For 20 years, they have been selecting the finest raw materials and using their traditional methods and expertise to produce the finest and tastiest prosciutto, salamis, pancetta, culatello and coppa di parma. Like the Parmigiano Reggiano cheese producers, the Parma Ham producers are also part of a consortium, and as such, must adhere to high standards and follow precise rules of production.

We will get an introduction of the prosciutto making process. Our tour starts with the trimming of the excess fat and rind of the pork thigh to give the ham its rounded shape and to assist in the salting process. The rind is treated with wet salt while the lean parts are sprinkled with dry salt. During a three week period, the ham is salted twice and placed in walk-in freezers with different temperatures. During this period, it slowly absorbs salt, loses moisture, and loses about 4% of its weight.

Our guide explaining the production process, the ham cellar and the “5 point crown” stamp.

In the next stage, the ham’s residual salt is removed and it is placed in a special room with controlled humidity and temperature for just over two months. While in this room, the salt penetrates even deeper and it is reduced by another 8-10%. We continue into a room with windows that are opened for the ham to dry over the next few months in natural process that will result in another weight loss of 8-10%.

The ham’s final move is to the cellar on the seventh month. In the cellar, important biochemical and enzymatic processes occur. Here it loses another 5% of weight but gains the distinct aroma and taste of the Param Ham.

The finished La Perla Prosciutto, a mixed plate of their products and me with Mr. Lafranchi.

At the end of the curing process, the ham is penetrated by a horse bone needle by experts who can verify its quality with a trained sense of smell. Finally, after a twelve month journey, the ham is inspected by the Parma Quality Institute and branded with the “5 pointed crown” as a guarantee to the consumer that the product is of the highest quality.

The tour gives us a great appreciation for the care that goes into making these products, and underscores why they are highly sought after. We move to the La Perla tasting room where we can try some of the local wines while enjoying lunch, which of course, includes pasta, cured meats, prosciutto, Parmesan cheese, bread and a dessert. It is always tough to get a group to leave because the Lafranchi family are great hosts who love to meet people from around the world. But we must leave, as one hour away, is a mecca for car enthusiasts.

The red arch at the Ferrari Museum entrance, the Ferrari 330 P3 and the AF Corse # 51.

Ferrari Museum

As we arrive at Maranello, we are greeted by a traffic circle that has a familiar silver prancing horse in the middle. This is undeniably, the home of Ferrari. Founded by Enzo Ferrari in 1929 as Scuderia Ferrari, the company sponsored drivers and manufactured race cars before moving into production of street-legal vehicles as Ferrari S.p.A. in 1947.

As we arrive to the Museum, we see a F1 race car in what looks like scaffolding and a welcoming bright red arch. Ferrari is the most successful Formula 1 team in history and has millions of loyal and exuberant fans worldwide. The motorsports cars in the museum are dedicated to the 90 years of Ferrari racing heritage. The cars will take your breath away.

The “Prancing Horse” logo, a 1950’s vintage race car and a classic Ferrari.

My favourite area of the museum is the Michael Schumacher exhibition dedicated to his 11 years of racing with Ferrari. The room has some of his F1 race cars on display in an awe-inspiring semi-circle with a video wall in the background playing highlights of his career. On the other side of the room is a lower wall dedicated to Ferarri champion drivers and an upper wall full of shiny trophies.

A few F1 cars from the Michael Schumacher exhibition, Ferrari champions and the trophies.

In addition to the racing automobiles, the museum also displays its most famous street cars through history, including the iconic Ferrari Testarossa. The Ferrari shop is full of items with the iconic item emblazoned on them, but like the high performance cars, they are pricey.

A Ferrari Portofino, a LaFerrari Aperta, and the Ferrari 5999 HY-KERS test “MULOTIPO.”

With your adrenalin pumping from being surrounded by automotive power, you will be ready to try a couple of unique experiences. If you are mechanically inclined, you will love the Pit Stop Experience, where they time you as you make a front tire change on a Formula 1 car. Those that “feel the need for speed” will drool at the sight of the unbelievable Scuderia Ferrari F1 simulators. After you climb into the pilot’s cockpit, you are given a brief explanation of how to use the paddles behind the steering wheel and the gear box. They can set up the simulator for regular driver or in a more advanced mode for “professionals.” You even get to choose one of the famous F1 tracks for your race experience. The simulator lets you feel the track surface including rubbing strips feel the breaking and throttle forces.

If you are interested, you can combine the museum ticket with a tour of the Ferrari track and factory. For the duration of the tour, you must remain on the company’s shuttle buses and no photos or video are allowed. The factory entrance has been kept the same as it was in 1947 and the track is where all of Ferrari’s competition and road cars have been tested since 1972.

Those that want to get behind the wheel can go to the nearby Autodromo di Modena race circuit and drive a Ferrari for 15 minutes or longer. The experience includes track information and safety protocols from a professional driver.

The tire changing Ferrari Pit Stop Experience and the Formula 1 racing simulators.

Balsamic Vinegar

After the heart racing Ferrari experience, we make a short early evening drive to a Balsamic Vinegar producer or “Acetaia” that was founded in the 1800s. The Paltrinieri Acetaia, established in 1845, maintains the family tradition and replenishes over 1000 barrels of balsamic using the experience handed down generation after generation. Adhering to the strict regulations and using local ingredients from the Trebiano and Lambrusco vineyards, Guido Paltrinieri guides the production of the vinegar must.

The company harvests 160,000 kilograms of grapes on their 25 acre farm, which produces 15,000 litres of balsamic vinegar. We will visit the warehouse attic to see the medium sized barrels made from durmast, chestnut, mulberry, cherry, acacia, ash and precious juniper wood.

The flavour garnered from the barrels, along with the aging process, result in the unique scent and flavour of the balsamic. In the tasting room, we try a range of balsamic they produce, and it is amazing how varied the taste can be in terms of the sweet and sour tones. They also vary in density. The denser the vinegar, the more of a syrupy texture it has. Mind you, this is not the balsamic you find at your local grocery store. A high quality Modena balsamic in a 100 ml bottle, and aged up to 25 years, can cost hundreds of dollars. The company also produces balsamic based products like Balsamotto, Acet-Up, Dulcia and Saba which are great for use in cooking or as a condiment, including on ice cream!

The Acetaia’s barrel sign, processing equipment, barrels of balsamic and the tasting room.

One of my favourite meals in Italy is at the Acetaia Paltrinieri restaurant. After our balsamic tasting and tour, we head across the courtyard to the rustic farm house restaurant. Just before we arrive to the restaurant doors, we are greeted with a glass of Pignoletto sparkling wine and crumbled Parmigiano Reggiano drizzled with DOP Modena Balsamic Vinegar. The balsamic and the cheese go so well together.

The Acetaia’s courtyard, restaurant entrance, Parmigiano with balsamic and their products.

Once inside, we are greeted with bottles of Lambrusco wine on the table, which everyone is quick to spot and partake in. Soon, a plate of a local flatbread called “tigelle” similar to an English muffin, and served warm, arrives with a spread. They are so good!

I have had two different first courses, and I’m not sure which I love more. One is a creamy risotto made with “riserva” balsamic vinegar, and the other is a pasta called Strozzapreti or “choke the priest” pasta. The name always makes me laugh, but the pasta, which also contains balsamic, is absolutely fantastic.

The second course is a meat course which is served with vegetables or salad. During my previous visits, I’ve enjoyed stuffed roast pig, chicken with ham or Balsamotto roast beef, with each dish including balsamic as an ingredient. Even my ice cream dessert contains balsamic. After a glass of a special local walnut liqueur called “nocino” or a nice espresso, we are on our way back to Bologna. It will be a late return to our hotel in Bologna but I’m sure we will venture out to find a nice place in the historic city centre to have a glass of wine and to talk about our amazing day in Emilia-Romagna.

Explore Europe With Us

Azorcan Global Sport, School and Sightseeing Tours have taken thousands to Europe on their custom group tours since 1994. Visit azorcan.net to see all our custom tour possibilities for your group of 26 or more. Individuals can join our “open” signature sport, sightseeing and sport fan tours including our popular Canada hockey fan tours to the World Juniors. At azorcan.net/media you can read our newsletters and listen to our podcasts.

Images compliments of Paul Almeida and Azorcan Tours.

Click here to read more of Paul’s travel series on Europe.

Business

Some Of The Wackiest Things Featured In Rand Paul’s New Report Alleging $1,639,135,969,608 In Gov’t Waste

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

Republican Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul released the latest edition of his annual “Festivus” report Tuesday detailing over $1 trillion in alleged wasteful spending in the U.S. government throughout 2025.

The newly released report found an estimated $1,639,135,969,608 total in government waste over the past year. Paul, a prominent fiscal hawk who serves as the chairman of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, said in a statement that “no matter how much taxpayer money Washington burns through, politicians can’t help but demand more.”

“Fiscal responsibility may not be the most crowded road, but it’s one I’ve walked year after year — and this holiday season will be no different,” Paul continued. “So, before we get to the Feats of Strength, it’s time for my Airing of (Spending) Grievances.”

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

The 2025 “Festivus” report highlighted a spate of instances of wasteful spending from the federal government, including the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) spent $1.5 million on an “innovative multilevel strategy” to reduce drug use in “Latinx” communities through celebrity influencer campaigns, and also dished out $1.9 million on a “hybrid mobile phone family intervention” aiming to reduce childhood obesity among Latino families living in Los Angeles County.

The report also mentions that HHS spent more than $40 million on influencers to promote getting vaccinated against COVID-19 for racial and ethnic minority groups.

The State Department doled out $244,252 to Stand for Peace in Islamabad to produce a television cartoon series that teaches children in Pakistan how to combat climate change and also spent $1.5 million to promote American films, television shows and video games abroad, according to the report.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) spent more than $1,079,360 teaching teenage ferrets to binge drink alcohol this year, according to Paul’s report.

The report found that the National Science Foundation (NSF) shelled out $497,200 on a “Video Game Challenge” for kids. The NSF and other federal agencies also paid $14,643,280 to make monkeys play a video game in the style of the “Price Is Right,” the report states.

Paul’s 2024 “Festivus” report similarly featured several instances of wasteful federal government spending, such as a Las Vegas pickleball complex and a cabaret show on ice.

The Trump administration has been attempting to uproot wasteful government spending and reduce the federal workforce this year. The administration’s cuts have shrunk the federal workforce to the smallest level in more than a decade, according to recent economic data.

Festivus is a humorous holiday observed annually on Dec. 23, dating back to a popular 1997 episode of the sitcom “Seinfeld.” Observance of the holiday notably includes an “airing of grievances,” per the “Seinfeld” episode of its origin.

Alberta

A Christmas wish list for health-care reform

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail and Mackenzie Moir

It’s an exciting time in Canadian health-care policy. But even the slew of new reforms in Alberta only go part of the way to using all the policy tools employed by high performing universal health-care systems.

For 2026, for the sake of Canadian patients, let’s hope Alberta stays the path on changes to how hospitals are paid and allowing some private purchases of health care, and that other provinces start to catch up.

While Alberta’s new reforms were welcome news this year, it’s clear Canada’s health-care system continued to struggle. Canadians were reminded by our annual comparison of health care systems that they pay for one of the developed world’s most expensive universal health-care systems, yet have some of the fewest physicians and hospital beds, while waiting in some of the longest queues.

And speaking of queues, wait times across Canada for non-emergency care reached the second-highest level ever measured at 28.6 weeks from general practitioner referral to actual treatment. That’s more than triple the wait of the early 1990s despite decades of government promises and spending commitments. Other work found that at least 23,746 patients died while waiting for care, and nearly 1.3 million Canadians left our overcrowded emergency rooms without being treated.

At least one province has shown a genuine willingness to do something about these problems.

The Smith government in Alberta announced early in the year that it would move towards paying hospitals per-patient treated as opposed to a fixed annual budget, a policy approach that Quebec has been working on for years. Albertans will also soon be able purchase, at least in a limited way, some diagnostic and surgical services for themselves, which is again already possible in Quebec. Alberta has also gone a step further by allowing physicians to work in both public and private settings.

While controversial in Canada, these approaches simply mirror what is being done in all of the developed world’s top-performing universal health-care systems. Australia, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland all pay their hospitals per patient treated, and allow patients the opportunity to purchase care privately if they wish. They all also have better and faster universally accessible health care than Canada’s provinces provide, while spending a little more (Switzerland) or less (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands) than we do.

While these reforms are clearly a step in the right direction, there’s more to be done.

Even if we include Alberta’s reforms, these countries still do some very important things differently.

Critically, all of these countries expect patients to pay a small amount for their universally accessible services. The reasoning is straightforward: we all spend our own money more carefully than we spend someone else’s, and patients will make more informed decisions about when and where it’s best to access the health-care system when they have to pay a little out of pocket.

The evidence around this policy is clear—with appropriate safeguards to protect the very ill and exemptions for lower-income and other vulnerable populations, the demand for outpatient healthcare services falls, reducing delays and freeing up resources for others.

Charging patients even small amounts for care would of course violate the Canada Health Act, but it would also emulate the approach of 100 per cent of the developed world’s top-performing health-care systems. In this case, violating outdated federal policy means better universal health care for Canadians.

These top-performing countries also see the private sector and innovative entrepreneurs as partners in delivering universal health care. A relationship that is far different from the limited individual contracts some provinces have with private clinics and surgical centres to provide care in Canada. In these other countries, even full-service hospitals are operated by private providers. Importantly, partnering with innovative private providers, even hospitals, to deliver universal health care does not violate the Canada Health Act.

So, while Alberta has made strides this past year moving towards the well-established higher performance policy approach followed elsewhere, the Smith government remains at least a couple steps short of truly adopting a more Australian or European approach for health care. And other provinces have yet to even get to where Alberta will soon be.

Let’s hope in 2026 that Alberta keeps moving towards a truly world class universal health-care experience for patients, and that the other provinces catch up.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoHunting Poilievre Covers For Upcoming Demographic Collapse After Boomers

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoState of the Canadian Economy: Number of publicly listed companies in Canada down 32.7% since 2010

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoCanadian university censors free speech advocate who spoke out against Indigenous ‘mass grave’ hoax

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoHousing in Calgary and Edmonton remains expensive but more affordable than other cities

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoJudge Declares Mistrial in Landmark New York PRC Foreign-Agent Case

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe “Disruptor-in-Chief” places Canada in the crosshairs

-

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoUK Police Pilot AI System to Track “Suspicious” Driver Journeys

-

Alberta1 day ago

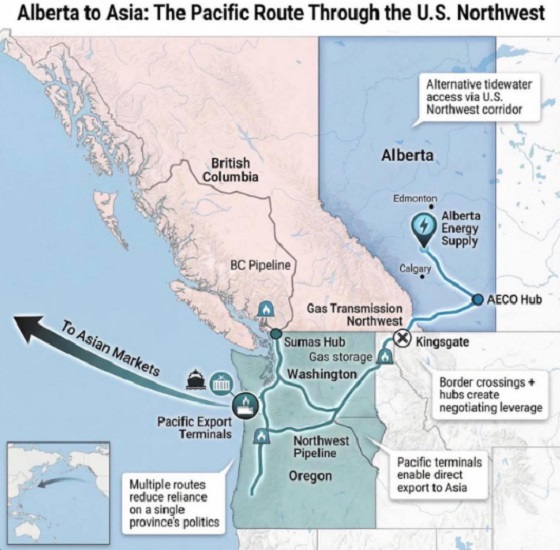

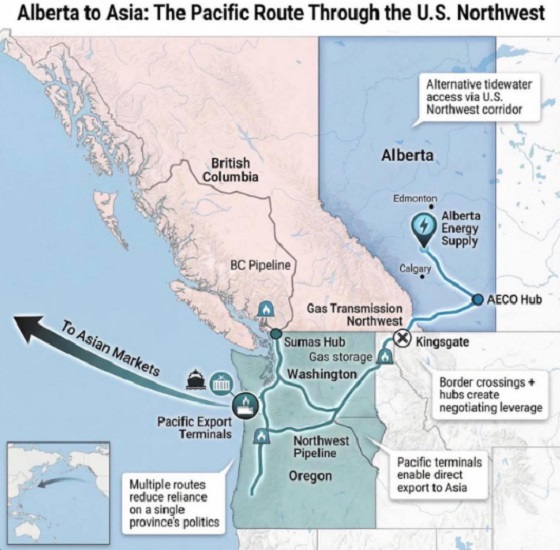

Alberta1 day agoWhat are the odds of a pipeline through the American Pacific Northwest?