Agriculture

The History of Evolution: from Darwin to DNA

The Malthus Problem

Almost everyone reading this will have had somewhere between a great grandparent or great great great grandparent who was alive when Darwin went on his legendary trip to The Galapagos Islands in 1831. Many people believe that Darwin came up with the idea for evolution on that trip, but the reality is that the theory predated his birth. What Darwin is famous for is a revolutionary new way of thinking about that idea.

In 1798, Thomas Malthus (of Malthusianism fame), figured out that the productivity of agriculture also meant a rise in the birthrate. On a finite planet, he could see no way that our food supplies would be able to keep up with our increase in population. The more we had to eat the more we had children and the math was not adding up to good news.

Humanity hitting a wall of that sort was a surprise at the time, because people back then saw the world the same way a lot of people still see it today. They believed that nature was growing toward a kind of perfection, like a tree reaching for the light –with humans, like a star, right at the top. But what did it mean if food security –humanity’s greatest success– was also our greatest threat? What did it mean to be successful if success could kill you? Just what light was this tree of nature striving toward?

It was in answering that question that Darwin had his big realization.

Darwin’s Genius

Most people saw evolution the same way most people today understand the idea of so-called pesticide-resistant ‘superweeds.” Most people imagine those weeds as the product of nature actively mutating around our efforts to control them. They imagine the plants intentionally changing in pursuit of survival, which means they imagined that the phrase survival of the fittest meant the ‘survival of the smartest and strongest.’

Darwin saw it for what it really was: animals and plant species sought life, but they weren’t striving to survive –they cannot imagine their future. Their subtle variances simply meant that some simply do survive. Having no foresight, all plants just do what they do, and are what they are. Sometimes their conditions are favourable to their survival and other times they are not, which is why 99.9% of species that have ever existed have gone extinct. With every species, time eventually wins.

A thirsty plant during a drought will not see its genes go forward, nor will a plant that prefers dry soils do well during rainy periods. So rather than nature being a tree, striving upward in search of ever and ever brighter light, Darwin’s big insight was that nature is simply a huge collection of lottery tickets where at least some forms of life are bound to win. And humans are not outside of that fact of nature.

While we’re all enormously alike, parents are always mixing DNA that has never been mixed before. Sometimes mutations –or the mixes themselves– create diseases or weaknesses that weaken or kill us. Other times, we are one of the few genetically lucky lottery winners to survive something like The Spanish Influenza –or, if we’re a weed, survive a farmer’s herbicide. In fact there are no super-weeds, or super-people, there are simply weeds and people that best suit the conditions they happen to be in. In the case of the aforementioned flu, the young and the old were the ones spared while often times it was those in the prime of their lives that did not survive.

Of course, winning this genetic lottery means that the surviving DNA gets to breed more of the subsequent generations. Taking that idea in the opposite direction; Darwin realized that it meant that every living thing was somehow derived from a common ancestor. This was a revolutionary idea at the time.

The churches at the time found these ideas threatening because they created a scientific form of slow-motion creation over which the church had no authority. But for science it was a slowly-evolving eureka moment. To them Darwin’s notion wasn’t dispelling creation, it was seeing it more deeply: fifty percent of the human genome is shared with bananas. That fact does feel like a miracle, and it adds a whole new meaning to the phrase, ‘we are what we eat.’

Of course none of this explained the mechanism by which nature accomplished these variations, nor could we know that the answer might resolve Malthus’s concerns about population.

The Discovery of Genes

Fortunately, in the 1840’s, not long after Darwin’s trip to the Galapagos, a meticulous scientist and monk (which was common at the time), was in the Czech Republic breeding pea plants. Mendel painstakingly crossbred tens of thousands of carefully prepared plants and then just as carefully studied the results. Over time and repetition he realized that there were both dominant and recessive traits that he could predict in subsequent generations.

Mendel was the first person to even imply the idea of genes –the mechanism by which Darwin’s lottery could be held.

By 1869 we had invented technologies that would allow us to look at living things more closely. That’s when a Swiss scientist named Miescher saw something in the nuclei of cells. He even wondered if it could explain Mendel’s heredity mechanism, but at the time no one saw much value in what would come to be known as DNA and RNA.

DNA was pretty simple stuff, made from a nucleotide alphabet of only four letters. But each of our cells contains about two meters of it and we have over ten thousand trillion cells. That’s literally about 20 million kilometers or 12½ million miles of DNA in each of us! If nature’s bothering to create all of that, there’s a reason. But what? It’s only made of four nucleotides. What could you possibly create with a four letter alphabet?

The Colour of Chromosomes

Chromosomes were discovered in 1888, primarily by a German named, Boveri. They got their name because they were really good at absorbing dyes, which makes them easy to see under a microscope (when a cell is dividing). Boveri linked them to the idea of heredity but it was the 1900’s before anyone else really studied them in an effective way.

Thomas Morgan is the reason why so many people associate fruit flies with science experiments. The flies bred so quickly that they were perfect for studying how chromosomes might be affecting heredity. Morgan did for the flies what Mendel did for the peas. And thanks to a mutated fly with the wrong coloured eyes, he was able to track inheritance to the point where many scientists were prepared to work from the assumption that chromosomes and DNA were in fact somehow involved in heredity.

Morgan won a Nobel Prize for his work with the flies, but even 30 years later there were still a lot of people who did not believe genes existed, or that DNA was all that important.

It was about 110 years after Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle, near the end of WWII in the 1940’s, before a brilliant Canadian named Oswald Avery managed to change a bacterium by intentionally introducing a trait from a different bacteria’s DNA. It was that experiment that very cleverly proved to everyone that DNA did in fact explain heredity –and it was so ingenious that there were many who felt Avery deserved two Nobel’s for proving it.

The Shape of Things to Come

With Avery’s discovery made, the race was on to explain DNA’s structure and to understand how it does what it does. If they could figure out the shape of a DNA molecule then science had a better chance of figuring out what it was doing. At the time, it was like trying to figure out how the pieces bolted together to make a bio-machine that made…us.

Many expected the brilliant Linus Pauling to be first the one to figure it out, but maybe knowledge acted as a form of blindness in that case. The people who did find it were fairly unlikely –they had come from a background of working on military weapons. Crick of the famous Watson and Crick didn’t even have a doctorate at the time, although his effort to get one would play a key role in their discovery.

Watson was like a Doogie Howser character –a child genius who had played a role on a popular radio game show. The problem was, he wasn’t very familiar with chemistry. Yet he and Watson’s found themselves trying to figure out how that little four-letter alphabet could be assembled into life. It’s why their discovery was as surprising as it was incredible.

Maurice Wilkins shares the Nobel Prize with Watson and Crick. He is the often-forgotten New Zealander who did a lot of the less glamorous work in developing X-Ray Crystallography that lead to the ability to take images of DNA. That was clearly going to help because, at the time, everyone was following Pauling’s lead –so they were working from the assumption that the DNA molecule’s shape was a triple helix.

The Woman Who Saw Things Clearly

Rosalind Franklin was the woman who figured how to actually take the pictures that Wilkins had theorized, but it was actually a student of hers (named Ray Gosling) who took the now-famous Photo 51. Gosling ended up being moved to work with Wilkins, who many feel shouldn’t have unilaterally showed Franklin’s images to Watson and Crick. But, having seen the image, they could now get their G’s C’s T’s and A’s into a double helix that led Watson and Crick to entirely re-think what they were doing.

Soon after, Franklin wrote a report on an even more detailed photo. That got passed from group leader to group leader at Cambridge until it eventually found its way to Watson and Crick. Using some impressively complex math developed for Crick’s PhD thesis, the two men now used Franklin’s measurements (without her knowledge), and they got the ‘ladder’ of the DNA lined up in such a way that it did produce the proteins that combine to form every living thing. This was an enormous eureka moment, as they say.

(You can actually help science by playing an on-line game called Fold it where you fold those resulting proteins in ways that can help science and humanity. The gamers who do so even get their work into respectable Journals like Nature.)

The reason Franklin went unmentioned for the Nobel was because applying complex math to a photo is easier than creating the complex math to apply to a photo. But had Watson, Crick and Wilkins not beat her to the solution she would have got the answer shortly thereafter, and she was the first person to realize that our DNA forms the subtle variances required to ensure our unique genetic codes.

There was a lot of sexism at the time and that likely played a role Franklin being overlooked but, in the end, even Watson –who had treated her quite badly– admitted so, and regretted that she had died shortly thereafter, preventing him from making proper amends. And of course the Nobel Prize is not given posthumously….

As for the DNA itself, once it was solved it looked easy. The verticals on the DNA ladder are a sugar, and the rungs are the nucleobases we need to make the proteins that fold together to make us. (Drug-based gene therapy is when a drug re-folds an improperly folded protein.) The rungs always have G with C, and T is always with A (unless it’s RNA, then the T is replaced with a U). It’s quite simple chemistry –if you’re a chemist.

In a much more recent development, in the spring of 2018 science was able to confirm a 1990’s theoretical discovery, meaning we also now know there is also i-motif DNA, which is a four strand knot or loop of (C)ytosine to (C)ytosine rungs. (There’s also A, Z, Triplex, Cruciform and G4 DNA shapes, but even scientists don’t know much about what’s going on with those yet, so if you can’t comprehend those you’re in extremely good company.)

After Crick, Watson, Wilkins and Franklin, the next most significant person in our understanding of DNA was the South African, Brenner. In 1960 he figured out that gene DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA in a process called transcription. The translated mRNA transports the genetic information from the cell nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it guides the production of the proteins.

By 1972 a Belgian named Walter Fiers figured out that the parts of our DNA that make the proteins are the genes, and the genes are the sections that organize the proteins to combine into everything a human being is. Shortly thereafter, Herbert Boyer, Stanley Norman Cohen and Paul Berg were the first people to intentionally transfer a gene. Their process got a bacteria to create foreign protein, essentially proving that genetic engineering was possible.

Soon after that, Marc Van Montagu and Jeff Schell found a little circular piece of DNA outside the chromosome of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. In nature it’s a bacteria that put tumors on trees, but they suspected it could also facilitate gene transfer between species in nature. By the early 80’s they had worked the Americans and the French to create the first genetically engineered plant –a variety of tobacco.

In 1974 Rudolph Jaenisch had engineered a mammal, creating the first mouse. That in turn incited a huge shift in medical research because that discovery made it possible to do experiments on exactly the same mouse over and over, which is obviously very helpful in scientific research.

Then, almost miraculously, in 1977, Carl Woese (and George E. Fox) made possibly the least-known yet most important discovery since Darwin himself, when they disproved Darwin’s notion of nature as a ‘tree of life.’ This later set Woese on a path that demonstrated the significance of Horizontal Gene Transfer. That discovery effectively saw Darwin’s ‘tree’ suddenly evolve into a bush –which demonstrated that, just as modern GMOs do, nature did and does move genes from one species to another, with the Sweet potato being a popular example. (Later, our human genome was found to be 8% virus.)

Enter Craig Venter in 2000. He and his team are the first to map the entire human genome. That same technology is now being used to map the genomes of countless plants and animals. It is through these processes that some diseases are discovered that relate to mistakes in copying the DNA code, and that lead to things like cancers.

By 2012, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, only the second and third woman in the bunch, make maybe the most practical discovery in genetics when they figure out how to use a technology called CRISPR to get nature itself to edit or patch genetic code. This process is so natural that if we use it to create a new food it isn’t even considered genetically modified because it comes about the very same way that nature does it.

That takes us to where science is today. But this begs the question, how does DNA actually work?

Cell Splits, DNA Snips and Cancer

When our cells split our 2 meters of DNA comes unzipped down the middle of the ‘ladder.’ But because it’s a code where Cs always link to G’s and T’s always link to A’s, it only takes about a second and nature has made a new piece of matching DNA and you have a whole new ‘ladder.’

We do this unzipping and recreating a lot with our colon cells because they only survive a few days; skin cells maybe a month; and like pretty much all cells, the liver cells get replaced constantly. But each individual one only replicates about once every 11-17 months. This explains why we’re often tired when we’re recovering from surgery. On top of any damage we have to repair, we have about 50-100 trillion cells and about 300 million die every minute, so it’s easy to see that our bodies are very busy.

For the most part these processes go extremely well, but it is possible to have a split go slightly wrong –that’s when a wrong letter gets in the wrong place. Biochemists call that a snip. Snips are how we get mutations that can sometimes give us cancer, and that’s why older people get more cancer. They’ve simply had more cell divisions –or more time for more splits and snips. This also explains why cancers will grow much faster in some parts of the body than in others –it depends on the rate of cell replacement.

Despite the fact that they sometimes can lead to cancer, snips are also what makes each of us just unique enough that some of us survive The Spanish Influenza pandemic while others do not. If you saw the film GATTACA, (so-named for the four nucleotides in DNA), a snip was Ethan Hawke’s advantage in the film.

Too much snipping and we die. Too little and we never evolve. Our existence literally balances between those two opposing concepts, hence our interest in genetic engineering –it’s like tipping the balance in our favour. And now we also tip it in nature’s favour too, which is why we don’t need baby cows for rennet, horseshoe crabs for the antibodies in their blood, or pigs for insulin. And, as an example, if we can get more ears of corn on a single plant, then we can leave more wild spaces for nature.

Conscious Modification

Once we understood that the genes were made of chunks of DNA that simply coded for proteins, we realized that the Natives who turned teosinte grass into modern corn –about 10,000 years ago– were actually doing a valuable yet blindfolded form of genetic engineering.

On a modern level, despite the fact that Darwin had pointed out that we are all descended from one species (about 3.8 billion years ago), scientists were still surprised when they started noticing that the genes that made a mouse eye for a mouse would amazingly make a fly’s eye on a fly. Before they knew it the scientists realized they –and we– share about 60% of our code with flies! We even have the genes for a tail, that gene just isn’t switched on. It’s both unifying and humbling in a way. All life shares the same interchangeable LEGO, we just build different things with it.

Today, with the help of supercomputers, we can map out the genome of things very quickly. We can also imagine what would be created if you mixed things that haven’t mixed yet because we know what the codes actually do in the plants we improve. This means the beneficial changes created by genetic engineering could have happened in nature, but our advantage is that we do it intentionally, when otherwise a growing population could easily starve while waiting for nature to stumble onto the answers that will feed a future world.

Today’s accurate computer models also allow scientists to avoid wasting time on crops that they can figure out won’t survive, or that may be allergenic, etc. That gives them more time to develop the plants that are fit to be food. If any of these changes seems unnatural, remember, Darwin didn’t actually use the term survival of the fittest to describe evolutionary success –he simply described it as, descent through modification. Genetic engineering is merely conscious, intentional modification.

Working With Nature

When a scientist makes a crop that has an insecticide ‘inside it,’ the insecticide is BT, or bacillus thuringiensis. Much like a bacteria created a sweet potato by inserting its genes into a potato, BT is a bacteria commonly found in soil that is deadly to certain bugs. It’s the very same BT that organic farmers spray on their crops because their rules mean they are barred from using the GMO BT strains that have the DNA coding to create the BT within the plant itself.

The BT in a GMO is still normal BT, but it’s a part of nature that makes very specific bug’s guts –which are alkaline, not acidic like ours– explode. That’s not dangerous for mammals for much the same reason that your mother doesn’t have to be afraid of Tiger Lilies but she should keep them away from her cat. As with dogs and chocolate, what can kill one species can be irrelevant to another. But both the BT and Tiger Lillies are natural, and BT is a great example of how science can use genetic engineering to protect beneficial insects.

Can humans make mistakes? Yes. They do so quite regularly. But on important things we do a lot of double checking, and our food has never undergone more testing, whereas nature creates random things like poisonous mushrooms etc. Fortunately, genetic engineering has been precise enough for long enough that it is now proving it can generate substantial gains for humans and our environment.

Far from being afraid of the manipulation of DNA, we should see nature as Darwin’s lottery, where nature produces mostly losing tickets. In contrast, genetic engineering permits the wildness of nature to exist while also allowing us to recognize and define the traits that farmers will need when it comes to growing the crops that will sustainably feed a growing world.

Which brings us back to Malthus and his math problem.

Malthus Meets the Green Revolution

What Malthus could or did not include in his calculations were human things like genetically precise plant breeding, mechanization, The Green Revolution (created by plant hybrids and nitrogen fertilizer), as well as advances in soil science, genetic engineering, and satellite-aided precision agriculture. He also didn’t know that education would lower birthrates, which means the population will actually start dropping to a sustainable level starting somewhere between 2050 and 2100.

As recently as 1968 people like Paul Ehrlich were writing best-selling books that made Malthusian predictions that hundreds of millions of people would be starving every year by the 1980’s. That obviously didn’t happen, thanks in large part to genetic science. In fact, there are fewer starving people today than ever before, and most of those are due to war, not any failings of agriculture.

A Rationally Optimistic Future

Humans cannot move forward using ignorance and fear. Our future depends on us proceeding forward with the inventiveness implied by Rational Optimism. We must be realistic, and yet at the same time we must take what we learn about nature and use it to help both ourselves and nature.

We cannot do our best for the environment, for our nutrition, or for feeding the world if we don’t use all of the tools that science has discovered on its march through time. That can be as simple as a Native American putting a fish for nitrogen on a corn seed 5,000 years ago, or a geneticist helping a plant develop drought tolerance in a lab.

In agriculture, and in life in general, humans are simply using what we know in the most productive ways we can find. Our knowledge of DNA, coupled with the love of nature that lead to the existence of the sciences, will be absolutely key to us succeeding in sustainably feeding a growing planet.

Note: If you would like a short shareable video version of this article it can be found here.

Agriculture

End Supply Management—For the Sake of Canadian Consumers

This is a special preview article from the:

U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade policy is often chaotic and punitive. But on one point, he is right: Canada’s agricultural supply management system has to go. Not because it is unfair to the United States, though it clearly is, but because it punishes Canadians. Supply management is a government-enforced price-fixing scheme that limits consumer choice, inflates grocery bills, wastes food, and shields a small, politically powerful group of producers from competition—at the direct expense of millions of households.

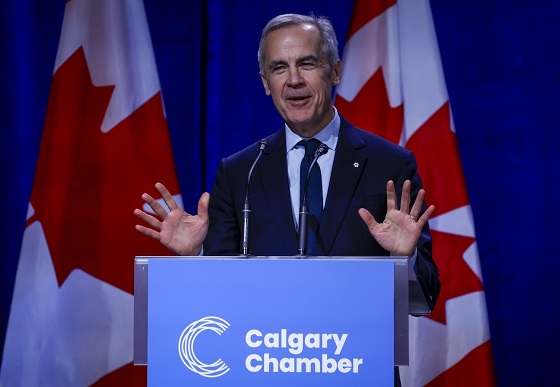

And yet Ottawa continues to support this socialist shakedown. Last week, Prime Minister Mark Carney told reporters supply management was “not on the table” in negotiations for a renewed United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, despite U.S. negotiators citing it as a roadblock to a new deal.

Supply management relies on a web of production quotas, fixed farmgate prices, strict import limits, and punitive tariffs that can approach 300 percent. Bureaucrats decide how much milk, chicken, eggs, and poultry Canadians farmers produce and which farmers can produce how much. When officials misjudge demand—as they recently did with chicken and eggs—farmers are legally barred from responding. The result is predictable: shortages, soaring prices, and frustrated consumers staring at emptier shelves and higher bills.

This is not a theoretical problem. Canada’s most recent chicken production cycle, ending in May 2025, produced one of the worst supply shortfalls in decades. Demand rose unexpectedly, but quotas froze supply in place. Canadian farmers could not increase production. Instead, consumers paid more for scarce domestic poultry while last-minute imports filled the gap at premium prices. Eggs followed a similar pattern, with shortages triggering a convoluted “allocation” system that opened the door to massive foreign imports rather than empowering Canadian farmers to respond.

Over a century of global experience has shown that central economic planning fails. Governments are simply not good at “matching” supply with demand. There is no reason to believe Ottawa’s attempts to manage a handful of food categories should fare any better. And yet supply management persists, even as its costs mount.

Those costs fall squarely on consumers. According to a Fraser Institute estimate, supply management adds roughly $375 a year to the average Canadian household’s grocery bill. Because lower-income families spend a much higher proportion of their income on food, the burden falls most heavily on them.

The system also strangles consumer choice. European countries produce thousands of varieties of high-quality cheeses at prices far below what Canadians pay for largely industrial domestic products. But our import quotas are tiny, and anything above them is hit with tariffs exceeding 245 percent. As a result, imported cheeses can cost $60 per kilogram or more in Canadian grocery stores. In Switzerland, one of the world’s most eye-poppingly expensive countries, where a thimble-sized coffee will set you back $9, premium cheeses are barely half the price you’ll find at Loblaw or Safeway.

Canada’s supply-managed farmers defend their monopoly by insisting it provides a “fair return” for famers, guarantees Canadians have access to “homegrown food” and assures the “right amount of food is produced to meet Canadian needs.” Is there a shred of evidence Canadians are being denied the “right amount” of bread, tuna, asparagus or applesauce? Of course not; the market readily supplies all these and many thousands of other non-supply-managed foods.

Like all price-fixing systems, Canada’s supply management provides only the illusion of stability and security. We’ve seen above what happens when production falls short. But perversely, if a farmer manages to get more milk out of his cows than his quota, there’s no reward: the excess must be

dumped. Last year alone, enough milk was discarded to feed 4.2 million people.

Over time, supply management has become less about farming and more about quota ownership. Artificial scarcity has turned quotas into highly valuable assets, locking out young farmers and rewarding incumbents.

Why does such a dysfunctional system persist? The answer is politics. Supply management is of outsized importance in Quebec, where producers hold a disproportionate share of quotas and are numerous enough to swing election results in key ridings. Federal parties of all stripes have learned the cost of crossing this lobby. That political cowardice now collides with reality. The USMCA is heading toward mandatory renegotiation, and supply management is squarely in Washington’s sights. Canada depends on tariff-free access to the U.S. market for hundreds of billions of dollars in exports. Trading away a deeply-flawed system to secure that access would make economic sense.

Instead, Ottawa has doubled down. Not just with Carney’s remarks last week but with Bill C-202, which makes it illegal for Canadian ministers to reduce tariffs or expand quotas on supply-managed goods in future trade talks. Formally signalling that Canada’s negotiating position is hostage to a tiny domestic lobby group is reckless, and weakens Canada’s hand before talks even begin.

Food prices continue to rise faster than inflation. Forecasts suggest the average family will spend $1,000 more on groceries next year alone. Supply management is not the only cause, but it remains a major one. Ending it would lower prices, expand choice, reduce waste, and reward entrepreneurial farmers willing to compete.

If Donald Trump can succeed in forcing supply management onto the negotiating table, he will be doing Canadian consumers—and Canadian agriculture—a favour our own political class has long refused to deliver.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal. Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Agriculture

The Climate Argument Against Livestock Doesn’t Add Up

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Livestock contribute far less to emissions than activists claim, and eliminating them would weaken nutrition, resilience and food security

The war on livestock pushed by Net Zero ideologues is not environmental science; it’s a dangerous, misguided campaign that threatens global food security.

The priests of Net Zero 2050 have declared war on the cow, the pig and the chicken. From glass towers in London, Brussels and Ottawa, they argue that cutting animal protein, shrinking herds and pushing people toward lentils and lab-grown alternatives will save the climate from a steer’s burp.

This is not science. It is an urban belief that billions of people can be pushed toward a diet promoted by some policymakers who have never worked a field or heard a rooster at dawn. Eliminating or sharply reducing livestock would destabilize food systems and increase global hunger. In Canada, livestock account for about three per cent of total greenhouse gas emissions, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Activists speak as if livestock suddenly appeared in the last century, belching fossil carbon into the air. In reality, the relationship between humans and the animals we raise is older than agriculture. It is part of how our species developed.

Two million years ago, early humans ate meat and marrow, mastered fire and developed larger brains. The expensive-tissue hypothesis, a theory that explains how early humans traded gut size for brain growth, is not ideology; it is basic anthropology. Animal fat and protein helped build the human brain and the societies that followed.

Domestication deepened that relationship. When humans raised cattle, sheep, pigs and chickens, we created a long partnership that shaped both species. Wolves became dogs. Aurochs, the wild ancestors of modern cattle, became domesticated animals. Junglefowl became chickens that could lay eggs reliably. These animals lived with us because it increased their chances of survival.

In return, they received protection, veterinary care and steady food during drought and winter. More than 70,000 Canadian farms raise cattle, hogs, poultry or sheep, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs across the supply chain.

Livestock also protected people from climate extremes. When crops failed, grasslands still produced forage, and herds converted that into food. During the Little Ice Age, millions in Europe starved because grain crops collapsed. Pastoral communities, which lived from herding livestock rather than crops, survived because their herds could still graze. Removing livestock would offer little climate benefit, yet it would eliminate one of humanity’s most reliable protections against environmental shocks.

Today, a Maasai child in Kenya or northern Tanzania drinking milk from a cow grazing on dry land has a steadier food source than a vegan in a Berlin apartment relying on global shipping. Modern genetics and nutrition have pushed this relationship further. For the first time, the poorest billion people have access to complete protein and key nutrients such as iron, zinc, B12 and retinol, a form of vitamin A, that plants cannot supply without industrial processing or fortification. Canada also imports significant volumes of soy-based and other plant-protein products, making many urban vegan diets more dependent on long-distance supply chains than people assume. The war on livestock is not a war on carbon; it is a war on the most successful anti-poverty tool ever created.

And what about the animals? Remove humans tomorrow and most commercial chickens would die of exposure, merino sheep would overheat under their own wool and dairy cattle would suffer from untreated mastitis (a bacterial infection of the udder). These species are fully domesticated. Without us, they would disappear.

Net Zero 2050 is a climate target adopted by federal and provincial governments, but debates continue over whether it requires reducing livestock herds or simply improving farm practices. Net Zero advocates look at a pasture and see methane. Farmers see land producing food from nothing more than sunlight, rain and grass.

So the question is not technical. It is about how we see ourselves. Does the Net Zero vision treat humans as part of the natural world, or as a threat that must be contained by forcing diets and erasing long-standing food systems? Eliminating livestock sends the message that human presence itself is an environmental problem, not a participant in a functioning ecosystem.

The cow is not the enemy of the planet. Pasture is not a problem to fix. It is a solution our ancestors discovered long before anyone used the word “sustainable.” We abandon it at our peril and at theirs.

Dr. Joseph Fournier is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. An accomplished scientist and former energy executive, he holds graduate training in chemical physics and has written more than 100 articles on energy, environment and climate science.

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoICYMI: Largest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Alberta9 hours ago

Alberta9 hours agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoWhile Western Nations Cling to Energy Transition, Pragmatic Nations Produce Energy and Wealth

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoUS Halts Construction of Five Offshore Wind Projects Due To National Security

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoBe Careful What You Wish For In 2026: Mark Carney With A Majority

-

Energy6 hours ago

Energy6 hours agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Energy8 hours ago

Energy8 hours agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade