Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Global Warming Predictions of Doom Are Dubious

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

What if the scariest climate predictions are more fiction than fact?

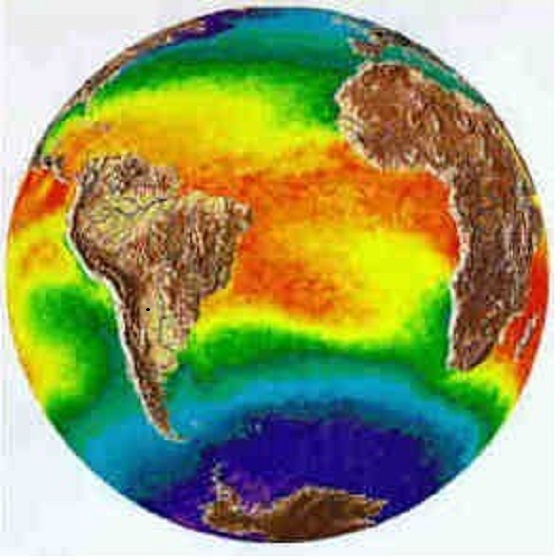

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) aims to highlight the urgent threats climate change poses. It projects severe consequences, including longer and more intense urban heat waves, as the World Resources Institute noted, along with increased storms, floods, and crop failures. IPCC claims that our current path leads to a temperature increase of at least three degrees Celsius above pre-industrial (circa 1750-1850) levels if the world does not drastically reduce carbon dioxide or just carbon emissions. However, this assessment and the attendant predictions are dubious.

The first uncertainty is the pre-industrial global temperatures. There were no precise thermometers at random sites or in major towns until late in the 19th century. Therefore, researchers use ice cores and lake and sea sediments as proxies. The U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration admits that pre-1880 data are limited. It provides many examples showing how even modern temperatures can be incomparable from region to region and from past to present and consequently are adjusted to approximate comparability.

What cannot be explained away is the Medieval Warm Period, which lasted from about 800 AD to around 1300 AD, and the subsequent cooling period that ‘bottomed’ about 1700 AD called the Little Ice Age. Human activity did not cause either one, and they were not merely regional phenomena confined to the North Atlantic and Western Europe. In the Middle Ages, Vikings settled in Greenland and were able to grow crops. The weather cooled dramatically, and they abandoned their colonies in the 15th century. During the Little Ice Age, there were many crop failures and famines in Europe, and the river Thames reliably froze over, with ice thick enough to hold winter fairs on.

Temperatures did not rise significantly until well into the 19th century. Suppose the recent temperature increase between one and one and one-half degrees Celsius is correct. This is only a third of the way toward a more tolerable (i.e., more livable, with less disease and fewer cold-related deaths) climate and cannot be termed “global boiling,” as the Secretary-General of the United Nations called it in 2023.

At three or more degrees of warming, IPCC researchers (“Climate Change 2023 Synthesis Report: Summary for Policymakers Sixth Assessment Report,” “AR6” pp. 15-16) have “high confidence” in more severe hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones; large floods; deadlier heatwaves and droughts; lower glacier-fed river flow; and lower crop yields.

Yet, their predictions are vague and generalized. So far, there are few signs that these calamities are increasing in frequency or intensity – hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons are not. Indeed, humanity is coping well: The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization observed that 2024 grain production was the second-highest on record.

Here are a few erroneous predictions the New American found: the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP)’s 2005 warning of 50 million climate refugees by 2010; the University of East Anglia’s 2000 prediction that the United Kingdom would rarely have snow in winter; and several early-2000s prognostications of the Arctic Ocean being ice-free in summer by 2016 – none has happened. A critique from May of 2020 of the thirty-eight models used to predict futures observed that the predictions of the amalgamated model used by the IPCC consistently and substantially overestimated actual warming.

Longer and hotter heat waves in cities are not the end of the world. They are unpleasant but manageable. Practical methods of urban cooling are spreading globally. Heat-related deaths are still far fewer than those from cold (by a ten-to-one ratio). If it gets hotter occasionally, humanity can and will survive.

Ian Madsen is the Senior Policy Analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Business

Ottawa Is Still Dodging The China Interference Threat

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lee Harding

Alarming claims out of P.E.I. point to deep foreign interference, and the federal government keeps stalling. Why?

Explosive new allegations of Chinese interference in Prince Edward Island show Canada’s institutions may already be compromised and Ottawa has been slow to respond.

The revelations came out in August in a book entitled “Canada Under Siege: How PEI Became a Forward Operating Base for the Chinese Communist Party.” It was co-authored by former national director of the RCMP’s proceeds of crime program Garry Clement, who conducted an investigation with CSIS intelligence officer Michel Juneau-Katsuya.

In a press conference in Ottawa on Oct. 8, Clement referred to millions of dollars in cash transactions, suspicious land transfers and a network of corporations that resembled organized crime structures. Taken together, these details point to a vulnerability in Canada’s immigration and financial systems that appears far deeper than most Canadians have been told.

P.E.I.’s Provincial Nominee Program allows provinces to recommend immigrants for permanent residence based on local economic needs. It seems the program was exploited by wealthy applicants linked to Beijing to gain permanent residence in exchange for investments that often never materialized. It was all part of “money laundering, corruption, and elite capture at the highest levels.”

Hundreds of thousands of dollars came in crisp hundred-dollar bills on given weekends, amounting to millions over time. A monastery called Blessed Wisdom had set up a network of “corporations, land transfers, land flips, and citizens being paid under the table, cash for residences and property,” as was often done by organized crime.

Clement even called the Chinese government “the largest transnational organized crime group in the history of the world.” If true, the allegation raises an obvious question: how much of this activity has gone unnoticed or unchallenged by Canadian authorities, and why?

Dean Baxendale, CEO of the China Democracy Fund and Optimum Publishing International, published the book after five years of investigations.

“We followed the money, we followed the networks, and we followed the silence,” Baxendale said. “What we found were clear signs of elite capture, failed oversight and infiltration of Canadian institutions and political parties at the municipal, provincial and federal levels by actors aligned with the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, the Ministry of State Security. In some cases, political donations have come from members of organized crime groups in our country and have certainly influenced political decision making over the years.”

For readers unfamiliar with them, the United Front Work Department is a Chinese Communist Party organization responsible for influence operations abroad, while the Ministry of State Security is China’s main civilian intelligence agency. Their involvement underscores the gravity of the allegations.

It is a troubling picture. Perhaps the reason Canada seems less and less like a democracy is that it has been compromised by foreign actors. And that same compromise appears to be hindering concrete actions in response.

One example Baxendale highlighted involved a PEI hotel. “We explore how a PEI hotel housed over 500 Chinese nationals, all allegedly trying to reclaim their $25,000 residency deposits, but who used a single hotel as their home address. The owner was charged by the CBSA, only to have the trial shut down by the federal government itself,” he said. The case became a key test of whether Canadian authorities were willing to pursue foreign interference through the courts.

The press conference came 476 days after Bill C-70 was passed to address foreign interference. The bill included the creation of Canada’s first foreign agent registry. Former MP Kevin Vuong rightly asked why the registry had not been authorized by cabinet. The delay raises doubts about Ottawa’s willingness to confront the problem directly.

“Why? What’s the reason for the delay?” Vuong asked.

Macdonald-Laurier Institute foreign policy director Christopher Coates called the revelations “beyond concerning” and warned, “The failures to adequately address our national security challenges threaten Canada’s relations with allies, impacting economic security and national prosperity.”

Former solicitor general of Canada and Prince Edward Island MP Wayne Easter called for a national inquiry into Beijing’s interference operations.

“There’s only one real way to get to the bottom of what is happening, and that would be a federal public inquiry,” Easter said. “We need a federal public inquiry that can subpoena witnesses, can trace bank accounts, can bring in people internationally, to get to the bottom of this issue.”

Baxendale called for “transparency, national scrutiny, and most of all for Canadians to wake up to the subtle siege under way.” This includes implementing a foreign influence transparency commissioner and a federal registry of beneficial owners.

If corruption runs as deeply as alleged, who will have the political will to properly respond? It will take more whistleblowers, changes in government and an insistent public to bring accountability. Without sustained pressure, the system that allowed these failures may also prevent their correction.

Lee Harding is a research fellow for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Tent Cities Were Rare Five Years Ago. Now They’re Everywhere

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canada’s homelessness crisis has intensified dramatically, with about 60,000 people homeless this Christmas and chronic homelessness becoming entrenched as shelters overflow and encampments spread. Policy failures in immigration, housing, monetary policy, shelters, harm reduction, and Indigenous governance have driven the crisis. Only reversing these policies can meaningfully address it.

Encampments that were meant to be temporary have become a permanent feature in our communities

As Canadians settle in for the holiday season, 60,000 people across this country will spend Christmas night in a tent, a doorway, or a shelter bed intended to be temporary. Some will have been there for months, perhaps years. The number has quadrupled in six years.

In October 2024, enumerators in 74 Canadian communities conducted the most comprehensive count of homelessness this country has attempted. They found 17,088 people sleeping without shelter on a single autumn night, and 4,982 of them living in encampments. The count excluded Quebec entirely. The real number is certainly higher.

In Ontario alone, homelessness increased 51 per cent between 2016 and 2024. Chronic homelessness has tripled. For the first time, more than half of all homelessness in that province is chronic. People are no longer moving through the system. They are becoming permanent fixtures within it.

Toronto’s homeless population more than doubled between April 2021 and October 2024, from 7,300 to 15,418. Tents now appear in places that were never seen a decade ago. The city has 9,594 people using its shelter system on any given night, yet 158 are turned away each evening because no beds are available.

Calgary recorded 436 homeless deaths in 2023, nearly double the previous year. The Ontario report projects that without significant policy changes, between 165,000 and 294,000 people could experience homelessness annually in that province alone by 2035.

The federal government announced in September 2024 that it would allocate $250 million over two years to address encampments. Ontario received $88 million for ten municipalities. The Association of Municipalities of Ontario calculated that ending chronic homelessness in their province would require $11 billion over ten years. The federal contribution represents less than one per cent of what is needed.

Yet the same federal government found $50 billion for automotive subsidies and battery plants. They borrow tonnes of money to help foreign car manufacturers with EVs, while tens of thousands are homeless. But money alone does not solve problems. Pouring billions into a bureaucratic system that has failed spectacularly without addressing the policies that created the crisis would be useless.

Five years ago, tent cities were virtually unknown in most Canadian communities. Recent policy choices fuelled it, and different choices can help unmake it.

Start with immigration policy. The federal government increased annual targets to over 500,000 without ensuring housing capacity existed. Between 2021 and 2024, refugees and asylum seekers experiencing chronic homelessness increased by 475 per cent. These are people invited to Canada under federal policy, then abandoned to municipal shelter systems already at capacity.

Then there is monetary policy. Pandemic spending drove inflation, which made housing unaffordable. Housing supply remains constrained by policy. Development charges, zoning restrictions, and approval processes spanning years prevent construction at the required scale. Municipal governments layer fees onto new developments, making projects uneconomical.

Shelter policy itself has become counterproductive. The average shelter stay increased from 39 days in 2015 to 56 days in 2022. There are no time limits, no requirements, no expectations. Meanwhile, restrictive rules around curfews, visitors, and pets drive 85 per cent of homeless people to avoid shelters entirely, preferring tents to institutional control.

The expansion of harm reduction programs has substituted enabling for treatment. Safe supply initiatives provide drugs to addicts without requiring participation in recovery programs. Sixty-one per cent cite substance use issues, yet the policy response is to make drug use safer rather than to make sobriety achievable. Treatment programs with accountability would serve dignity far better than an endless supply of free drugs.

Indigenous people account for 44.6 per cent of those experiencing chronic homelessness in Northern Ontario despite comprising less than three per cent of the general population. This overrepresentation is exacerbated by policies that fail to recognize Indigenous governance and self-determination as essential. Billions allocated to Indigenous communities are never scrutinized.

The question Canadians might ask this winter is whether charity can substitute for competent policy. The answer is empirically clear: it cannot. What is required before any meaningful solutions is a reversal of the policies that broke it.

Marco Navarro-Genie is vice-president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and co-author with Barry Cooper of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023).

-

Business20 hours ago

Business20 hours agoICYMI: Largest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Alberta12 hours ago

Alberta12 hours agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoUS Halts Construction of Five Offshore Wind Projects Due To National Security

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoWhile Western Nations Cling to Energy Transition, Pragmatic Nations Produce Energy and Wealth

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoBe Careful What You Wish For In 2026: Mark Carney With A Majority

-

Energy9 hours ago

Energy9 hours agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Energy11 hours ago

Energy11 hours agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade

-

Business10 hours ago

Business10 hours agoSocialism vs. Capitalism