Energy

Archaic Federal Law Keeps Alaskans From Using Abundant Natural Gas Reserves

Welcome to The Rattler, a Reason newsletter from me, J.D. Tuccille. If you care about government overreach and tangible threats to everyday liberty, you’re in the right place. Did someone forward this to you? You may freely choose to subscribe right here.

Alaska is an energy behemoth with massive reserves of oil, natural gas, and petroleum. It also, oddly, faces a looming natural gas shortage—not good for a state where half of electricity production depends on the stuff. The problem is that most natural gas deposits are far from population centers and pipelines to transport the gas don’t yet exist and may never be built. So, to get gas to Alaskans, you need to transport it by ship. But federal law requires that only U.S.-flagged liquid natural gas (LNG) carriers be used, and there aren’t any.

Vast Energy Reserves

Alaska really is a powerhouse. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the state’s “proved crude oil reserves—about 3.2 billion barrels at the beginning of 2022—are the fourth-largest in the nation.” It’s “recoverable coal reserves are estimated at 2.8 billion tons, about 1% of the U.S. total.” And, most impressively, Alaska’s “proved natural gas reserves—about 100 trillion cubic feet—rank third among the states.”

With that much natural gas to draw on, it’s no wonder the state gets about half of its total electricity from generators powered by natural gas, with roughly three-quarters of power to the main Railbelt grid coming from gas. Nevertheless, the lights could soon flicker—and a lot of people’s furnaces and stoves sputter—because of lack of access to the vast natural gas reserves.

“Alaska lawmakers are searching for solutions to a looming shortage of natural gas that threatens power and heating for much of the state’s population,” Alaska Public Media reported in February. “The state’s largest gas utility is warning that shortfalls could come as soon as next year – and imports are years off.”

But Not Where It’s Needed

It turns out that the gas Alaskans use comes not from the vast North Slope reserves, but from wells in the Cook Inlet. Most companies say it’s not worth their time to drill there, and so sold their leases to Hilcorp over 10 years ago. Hilcorp is a Texas-based company that specializes in getting the most out of declining oil and gas wells—and the existing Cook Inlet wells are decades old and long past their peak. The company expects to produce about 55 billion cubic feet of gas this year but predicts production will fall to 32 billion cubic feet in 2029.

If few companies want to drill more wells in the Cook Inlet, it makes sense to draw on the natural gas in another part of Alaska, the North Slope. In 2020, federal and state officials approved a pipeline to transport gas from the North Slope to the Kenai Peninsula for local use as well as export. But building another pipeline across rugged Alaska is a massive undertaking and the project has struggled to find backers. It won’t be ready for years, if ever.

That leaves transportation by sea. The gas could be transported from the North Slope by LNG carrier and offloaded in the populated areas where it’s needed. But there’s a hitch.

No Ships for You

A century ago, Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (better known as the Jones Act) to prop up the country’s shipping industry. The law “among other things, requires shipping between U.S. ports be conducted by US-flag ships,” according to Cornell Law Schools’s Legal Information Institute. The ships must also be built here. So, to move natural gas from one part of Alaska to another, you need American LNG carriers. And here we find another shortage.

“LNG carriers have not been built in the United States since before 1980, and no LNG carriers are currently registered under the U.S. flag,” the U.S. Government Accountability Office found in 2015. And while there’s lots of demand for more LNG carriers for the export market, not just for Alaska, “U.S. carriers would cost about two to three times as much as similar carriers built in Korean shipyards and would be more expensive to operate.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection did make an exception to let foreign LNG carriers transport U.S. natural gas to Puerto Rico earlier this year, but only because the gas was first piped to Mexico before being loaded onto ships. Isolated Alaska doesn’t have that option.

The feds are diligent about prosecuting Jones Act violations, too. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice imposed a $10 million penalty on an energy exploration and production company for transporting a drill rig from the Gulf of Mexico to Alaska’s Cook Inlet in a foreign-flagged vessel. That company’s intention was to bring more natural gas to market in Alaska.

Given the law’s strict terms and the government’s enthusiastic enforcement, “it will be perfectly legal for ships from other countries to pick up liquid natural gas from the new production facility in northern Alaska—as long as they don’t stop at any other American ports to unload,” Reason’s Eric Boehm noted in 2020.

When Boehm wrote, the century-old protectionist law contributed to high prices for Alaskans. Now it may actually precipitate a crisis by making it effectively illegal for energy companies to ship abundant natural gas from one part of the state to eager customers in another.

A Law In Need of Repeal or Relief

In 2018, the Cato Institute’s Colin Grabow, Inu Manak, and Daniel J. Ikenson delved into the damage done by the Jones Act in terms of higher costs and distorted markets, even as it fails to keep the domestic shipping industry from withering. The authors called for the law’s repeal. Failing that, they recommended the federal government “grant a permanent exemption of the Jones Act for Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Guam.” These isolated jurisdictions suffer the most from Jones Act protectionism and would benefit from greater leeway for foreign shipping.

Until that happens, Alaskans may suffer from a natural gas shortage while having plenty of the stuff to sell to the rest of the world.

– J.D.

Alberta

What are the odds of a pipeline through the American Pacific Northwest?

From Resource Works

Can we please just get on with building one through British Columbia instead?

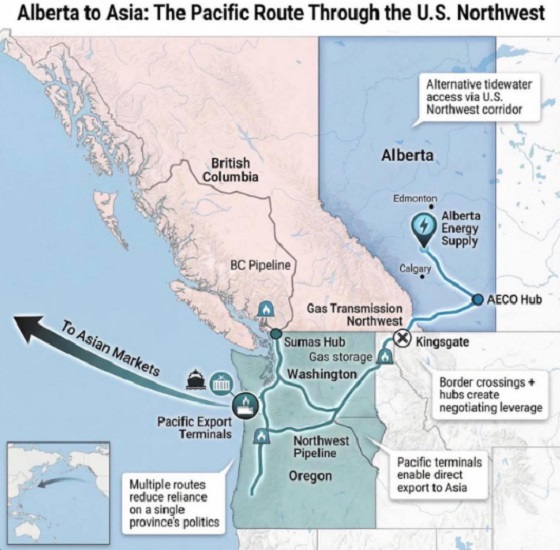

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is signalling she will look south if Canada cannot move quickly on a new pipeline, saying she is open to shipping oil to the Pacific via the U.S. Pacific Northwest. In a year-end interview, Smith said her “first preference” is still a new West Coast pipeline through northern British Columbia, but she is willing to look across the border if progress stalls.

“Anytime you can get to the West Coast it opens up markets to get to Asia,” she said. Smith also said her focus is building along “existing rights of way,” pointing to the shelved Northern Gateway corridor, and she said she would like a proposal submitted by May 2026.

Deadlines and strings attached

The timing matters because Ottawa and Edmonton have already signed a memorandum of understanding that backs a privately financed bitumen pipeline to a British Columbia port and sends it to the new Major Projects Office. The agreement envisages at least one million barrels a day and sets out a plan for Alberta to file an application by July 1, 2026, while governments aim to finish approvals within two years.

The bargain comes with strings. The MOU links the pipeline to the Pathways carbon capture network, and commits Alberta to strengthen its TIER system so the effective carbon credit price rises to at least 130 dollars a tonne, with details to be settled by April 1, 2026.

Shifting logistics

If Smith is floating an American outlet, it is partly because Pacific Northwest ports are already drawing Canadian exporters. Nutrien’s plan for a $1-billion terminal at Washington State’s Port of Longview highlighted how trade logistics can shift when proponents find receptive permitting lanes.

But the political terrain in Washington and Oregon is unforgiving for fossil fuel projects, even for natural gas. In 2023, federal regulators approved TC Energy’s GTN Xpress expansion over protests from environmental groups and senior officials in West Coast states, with opponents warning about safety and wildfire risk. The project would add about 150 million cubic feet per day of capacity.

A record of resistance

That decision sits inside a longer record of resistance. The anti-development activist website “DeSmog” eagerly estimated that more than 70 percent of proposed coal, oil, and gas projects in the Pacific Northwest since 2012 were defeated, often after sustained local organizing and legal challenges.

Even when a project clears regulators, economics can still kill it. Gas Outlook reported that GTN later said the expansion was “financially not viable” unless it could obtain rolled-in rates to spread costs onto other utilities, a request regulators rejected when they approved construction.

Policy direction is tightening too. Washington’s climate framework targets cutting climate pollution 95 percent by 2050, alongside “clean” transport, buildings, and power measures that push electrification. Recent state actions described by MRSC summaries and NRDC notes reinforce that direction, including moves to help utilities plan a transition away from gas.

Oregon is moving in the same direction. Gov. Tina Kotek issued an executive order directing agencies to move faster on clean energy permitting and grid connections, tied to targets of cutting emissions 50 percent by 2035 and 90 percent by 2050, the Capital Chronicle reported.

For Smith, the U.S. corridor talk may be leverage, but it also underscores a risk, the alternative could be tougher than the Canadian fight she is already waging. The surest way to snuff out speculation is to make it unnecessary by advancing a Canadian project now that the political deal is signed. As Resource Works argued after the MOU, the remaining uncertainty sits with private industry and whether it will finally build, rather than keep testing hypothetical routes.

Resource Works News

Business

The “Disruptor-in-Chief” places Canada in the crosshairs

Not for the first time, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Policymaker of the Year is not a Canadian.

In 2019, our laureate was Xi Jinping, leader of the People’s Republic of China, whose long arm reached far into many aspects of policymaking in our nation’s capital.

That helps to underline our intention in conferring this recognition. Policy influence can be used to Canada’s benefit or detriment. In naming our annual Policymaker of the Year, MLI does not endorse their policies; instead, we seek to draw to the attention of Canadians those people who have had the most influence on public policy in this country – for good or ill – in the past year.

And in 2025, who can deny that US President Donald Trump, the Disruptor-in-Chief, has exercised an outsized influence on Canadians – on their hopes and fears, on their political preferences, and, most importantly for our purposes, on the policies pursued by the Canadian government?

How has Donald Trump spurred policy change in Canada? Let us count the ways:

First, set aside for the moment any focus on specific policy areas and just think about the President’s style and strategy. Anyone who has read The Art of the Deal knows that Trump is quite straightforward in avowing that his dealmaking strategy sets out to frighten and intimidate the other party with a degree of unpredictability, bravado, and unwillingness to be bound by past assumptions that is sometimes just breathtaking to contemplate.

On the other hand, what on the surface appears to his opponents as simply irrational is in fact nothing of the sort. He sets out to frighten and intimidate, but he also sets out to get deals done, which cannot happen with negotiating partners paralyzed by fear. And in fact, the list of deals he has done in less than a year in office is impressive: NATO members have made big commitments to increase defence spending, the war in Gaza is paused by a (shaky) ceasefire of his design, trade deals have been struck with many partners, including the EU, the UK, Mexico, and even China … though notably, not with Canada.

Here at home, Trump has riled Canadians with his comments about annexation and disputed borders, laid a heavy finger on the 2025 electoral scales, and met repeatedly with Prime Minister Mark Carney – but equally repeatedly sent him on his way with little to show for the Prime Minister’s efforts as supplicant. Policies that seemed settled, like our purchase of the F-35 fighter jet, our deep integration with the US economy, and our feeble attempts at even-handedness in the conflict in the Middle East, all seem to have fallen victim to Ottawa’s ill-advised urge to stick a finger in Donald Trump’s eye, whatever the cost.

Like it or not, Trump has reminded Canadians in no uncertain terms that America is the elephant and we are, if not exactly a mouse, certainly a beast whose wellbeing depends on American forbearance and good will. The question of whether we can calm the rampaging elephant and charm him into a better humour or fall back on much less profitable relations with other countries far away is THE question that will preoccupy policymakers in Ottawa this year and for several years to come.

It is against this backdrop that several major dimensions of Canada-US relations have been thrust into the spotlight – none more dramatically than trade.

Weaponized Tariffs and Fractured Trade

Tim Sargent

For many Canadians, Donald Trump’s re-election on November 5, 2024, while not a cause for celebration, was also not an existential threat to our economy. After all, when Trump was first elected in 2016, his threats to tear up the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) ultimately came to nothing, and the new version of NAFTA that was negotiated by the US, Canada, and Mexico (we call it CUSMA, the Americans call it USMCA), was broadly similar to its predecessor, with almost all Canadian goods able to enter the US market tariff-free.

That complacency was almost immediately shattered when the President, even before his inauguration, announced his intent to slap a tariff of 25 per cent on Canadian (and Mexican exports), supposedly in response to Canada’s failure to stop fentanyl from crossing over the US border. The shock was rapid, and the implications unmistakable.

Once in office, Trump made good on his threat and imposed the 25 per cent tariff on all Canadian exports except energy, which was subject to “only” a 10 per cent tariff. The sheer interconnectedness of the North American economy forced Trump to partially back down and exempt CUSMA-compliant goods from the tariffs. However, because they raised input costs for US manufacturers, Trump opened another front by slapping tariffs on steel, aluminum, autos, copper, lumber, and furniture in the name of national security, overriding the CUSMA treaty that he had signed. While these tariffs apply to all countries, these are all commodities for which Canadian exporters are very dependent on the US market, and which are very important for the Canadian economy.

While trade disputes with the US have not been unknown since the signing of the original Canada-US Free Trade Agreement in 1988 – softwood lumber is the most obvious example – no one expected Trump to take aim at the whole Canada–US trading relationship, which accounts for almost a quarter of our GDP. This escalation marks a break not just with economic norms but with decades of strategic restraint.

None of this augers well for the negotiations for the renewal of CUSMA, which are supposed to conclude in the summer of 2026, or the broader Canada-US trading relationship. Indeed, it is not clear that the renewal document will be worth the paper it is written on, given that Trump has shown no compunction in violating the terms of the original agreement. Perhaps even more fundamentally, the President, reflecting a broader strand of America-first nationalism, simply does not see trade as a mutually beneficial activity; rather, it is a zero-sum game in which the only way for the US to win is for others to lose. The fact that basic economics says the opposite seems to be neither here nor there.

All this leaves Canadian policymakers with some unpleasant alternatives. While the Carney government originally attempted to retaliate by imposing tariffs of its own, the reality is that these are pinpricks to the US, for which Canadian exports are only a few percentage points of GDP. Furthermore, tariffs hurt Canadian consumers. The other alternative, which the government is now pursuing, is to diversify Canada’s trade away from the US. However, Canadian governments have been trying to reduce their reliance on the United States since at least the 1970s, with little success. Geography and economic gravity continue to dominate: the US will always be the most obvious market for our exports, even with tariffs.

Perhaps the most that Canadians can hope for is that Americans will, as has happened in the past, come to realize that a close and stable trading relationship with Canada is in their national interest just as much as it is in ours.

Trade Tensions Fuel Canadian Oil Revival

Heather Exner-Pirot

Donald Trump’s tariffs and threat to the Canadian economy have meaningfully shifted both the public understanding and attitude towards oil and gas. Perhaps in the past it could be seen simply as something Alberta produced, an embarrassing source of global emissions. After 2025, it became clear how essential oil production is both to our economic health and our global standing.

Oil is Canada’s largest export, and most of it goes to the United States. When Trump declared in January 2025 that “we don’t need their oil and gas. We have more than anybody,” it was a tell. Canadian oil and gas is precisely the thing we produce that the United States needs more than anything else. In fact, that same month the US imported a record amount of Canadian crude oil: 4.27 million barrels; the most any country has ever imported from another in the history of the world.

This newfound appreciation of oil and its geopolitical importance brought a long-dead idea back to life: an oil pipeline to the northwest coast of British Columbia, the value of which has always been in diversifying our market for heavy oil from the US to Asia. The source of hard fought culture wars in the 2010s before being approved in 2014, rejected by Trudeau in 2018, and handed the final indignity of a tanker ban in 2019, a Northern Gateway-type pipeline is now not only possible, but even likely. In every public opinion poll in 2025, such a pipeline has enjoyed majority support. It is the centrepiece of the landmark MOU between the federal and Alberta government that has as an explicit goal increasing oil and gas production.

Canada has always had the resources of an energy superpower. Trump’s threats have done more to give us the ambition of one than anyone or anything before him.

“Elbows up” and the New Anti-American Nationalism

Mark Reid

Donald Trump’s return to the White House drastically altered the course of Canadian politics. The ensuing fallout – fuelled by threats of tariffs and incendiary “51st state” rhetoric – became the key catalyst that propelled Mark Carney’s Liberals to victory on an “elbows up” platform.

This resurgent Canadian nationalism was defined by a sharp strain of anti-Americanism in general, and a profound dislike of Trump in particular.

As Trump slapped tariffs on Canada (and mused about annexing Greenland), the Prime Minister and provincial leaders promised a “Team Canada” approach to counter the President’s aggression. Canadian politicians from coast to coast earnestly vowed to remove interprovincial trade barriers, back major national projects, and present a common front.

That unity quickly faded.

Faced with new rounds of tariff threats, Carney’s government shifted to diplomatic conciliation, rolling back the Digital Sales Tax and offering border security concessions to avert economic disaster. Supporters called it pragmatism; critics called it a surrender.

Meanwhile, the Team Canada vision turned out to be a mirage. Interprovincial squabbles over a bitumen pipeline to tidewater in BC persists, while a multi-million-dollar Ontario anti-tariff ad, which aired on US television, infuriated Trump.

These internal divisions underscore a dangerous reality: Canada’s very sovereignty may be at risk. The US President’s recent “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine clearly articulates his vision of American hegemony over the Americas, with Canada, presumably, as a sort of vassal state. The federal government now faces an impossible task – buying time in the hope that the US political climate shifts, while protecting Canadian autonomy from an American president who sees it as negotiable.

Smashing the Overton Window on social policy

Peter Copeland

Donald Trump is polarizing for good reason. He is rude, crude, lewd, and norm-breaking to an extraordinary degree: a former Manhattan Democrat and social liberal whose transgressiveness and contempt for precedent embody many of the very cultural tendencies the left has long celebrated. His impulsiveness seems to threaten alliances and raise geopolitical risks by the day – yet he now leads the most effective conservative movement in decades.

He also possesses unusual strengths. His entrepreneurial instinct has allowed him to see the gap created by an oblivious, or unwilling, left- and right- establishment political class on trade, immigration, cultural and social decline – and to seize the opportunity. His unfiltered political style contrasts sharply with the scripted, risk-averse habits of career politicians and the professional-managerial class. He seeks no validation from the Davos set or the media-academic establishment, making him unafraid to challenge orthodoxy. Trump’s rise is a sharp indictment of liberal elites on both sides of the political spectrum, who proved incapable of addressing the deep social and economic issues that he foregrounded from the outset of his presidency.

On issues like gender identity, DEI, and mass migration, rooted in an extreme open-society ideology of hyper-individualism and autonomy, establishment leaders had long been unwilling even to acknowledge the problems. Then Trump came along and threw open the Overton window on just about every issue.

For Canada, Trump’s impact is mixed. He expanded the envelope of the politically possible on topics thought untouchable just years ago, but his abrasive style has made Canadian elites – whose defining characteristic is anti-Americanism – more reluctant to pursue parallel reforms. On immigration, borders and defence, Ottawa is now moving; on gender, DEI, and education, it is retreating behind “Trump did it, so we won’t.”

Shredding Canada’s US security blanket

Richard Shimooka

President Trump’s successful upending of American foreign policy in 2025 has had profound and potentially long-term consequences, but few are as acutely felt as the changes he has forced upon the Canada-US security relationship. Trump’s actions have effectively ended the decades-long expectation that the United States would forever underwrite Canada’s defence and security, forcing a sea-change in Ottawa’s strategic calculus.

Since the Second World War, the foundation of the Canada-US security and economic relationship has been an interlocking system of security guarantees through alliances and free trade blocs. This synergistic mix, which bound states like Canada to a rules and values based international order conceived in Washington, allowed Canada to maintain a relatively small defence footprint, relying instead on overwhelming American firepower to deter its enemies.

However, Trump’s skepticism towards this foundation, evident since his first term, consolidated into decisive policy changes in his second term. By launching a devastatingly counterproductive trade war against Canada and other major trading partners and directly questioning the value of major alliances like NATO, he effectively declared America’s security commitments are no longer unconditional.

For Canada, this has meant a new urgency to foot a larger portion of the bill for continental security, a renewed focus on securing both the Canada-US border and the Arctic, and for finally meeting long-standing pledges to spend two per cent of GDP on NATO.

Ironically, while Trump’s pressure tactics have succeeding in pushing Canada (and other allies like Japan and Germany) to increase defence spending and become more self-sufficient, it comes at the cost of America’s ability to lead like-minded states. As US leverage wanes, Trump’s strategy may end up pushing America’s allies into the arms of strategic rivals like China.

Without American global leadership, states may prioritize a narrower brand of self-interest – one that is counterproductive to America’s overall strategic ends. Observe how Canada is now looking to rebuild its economic relationship with the People’s Republic of China, not merely for trade, but as a deliberate economic counterweight to its highly integrated trade relationship with the United States.

This impulse will likely be shared by many US allies. Indeed, allied nations in Southeast Asia may begin to doubt Washington’s commitment to the current geopolitical alignment and seek to balance their relationship with China. Some may even fall further into Beijing’s grasp, becoming the 21st-century equivalent of tributary states.

“Trump the Peacemaker” and the Politics of Force

Casey Babb

Donald Trump’s bold and fearless foreign policy decisions – especially regarding Israel’s war in Gaza and the broader Middle East – make him one of the most consequential and transformative political leaders in a generation. His combination of disruption, recalibration, and strategic risk-taking sought to redirect the trajectory of the Middle East in ways few leaders have attempted.

Some of these changes began during Trump’s first administration. The Abraham Accords, which normalized relations between Israel and several Arab states, reflected a shift toward open regional co-operation against shared security concerns. His decisions, like recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and cutting aid to Palestinian institutions, were commonsense corrections to what he viewed as unnecessary diplomatic ambiguities.

However, his most transformative actions in the Middle East happened in the aftermath of the October 7, 2023, Hamas terror attacks on Israel. From his 20-point plan for peace in Gaza and his efforts to bring home hostages, to the “12 Day War” between Israel and Iran, Trump made it clear that America’s support for Israel remains unwavering – signalling that Washington is willing to take decisive action in the Middle East to protect US and allied security.

Beyond the Middle East, Trump’s approach to China marked a sharp departure from previous presidents. Replacing engagement tactics with tariffs, export controls, and the framing of China as a key rival, Trump pushed for a shift in US policy that continues in his second term in office.

In Europe, Trump’s record on the Russia-Ukraine war is mixed. The President has pressured NATO allies to carry a greater load in terms of supporting Ukraine, and the US has continued to provide Kyiv with lethal military aid. However, critics worry about Trump’s personal relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin: as the peace negotiations continue, will Ukraine eventually be sacrificed for American expediency?

Conclusion

Trump’s legacy remains unwritten. It may destabilize Western institutions, or it may be the jolt needed to shake a complacent boomer establishment out of its decadent, dogmatic slumbers.

Trump has clearly shifted the geopolitical landscape in both Canada and around the world – in ways no conventional figure could have. It is worth asking: would Europe have increased defence spending without American pressure? Would Canada have taken border security, immigration, defence, or energy policy seriously?

Even conservative governments – often differing little from liberal ones in practice – have lacked the capital or resolve to confront entrenched bureaucracies, and it remains doubtful whether any old-school Canadian libertarian-oriented fusionist, or a typical Wall Street Republican in the US, would have had what it took to win, yet alone enact the needed the reforms.

Trump was, and is, very much the man for the moment. Whether this shift leads to renewal or decline, only time will tell. Those same disruptive instincts have defined his approach to the world stage as well, reshaping geopolitics in ways Canadians cannot ignore.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Tim Sargent is a senior fellow and the director of Domestic Policy at MLI.

Heather Exner-Pirot is a senior fellow and MLI’s director of Energy, Natural Resources, and the Environment.

Mark Reid is the senior editor at MLI.

Peter Copeland is the deputy director of Domestic Policy at MLI.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at MLI.

Casey Babb is the director of MLI’s The Promised Land program.

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoWhy is Canada paying for dairy ‘losses’ during a boom?

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoFord’s EV Fiasco Fallout Hits Hard

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoTop constitutional lawyer warns against Liberal bills that could turn Canada into ‘police state’

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMortgaging Canada’s energy future — the hidden costs of the Carney-Smith pipeline deal

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoAustralian PM booed at Bondi vigil as crowd screams “shame!”

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoEnd Supply Management—For the Sake of Canadian Consumers

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoCanada’s EV gamble is starting to backfire