National

Trudeau gov’t considered using term ‘heat-flation’ to link rising costs with ‘climate change’

From LifeSiteNews

Recently revealed documents show that members of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s cabinet were looking to associate rising inflation in Canada with “climate change” by using the term “heat-flation,” but abandoned the idea after negative feedback from polls.

The documents show that Trudeau’s own Privy Council Office in an April 24 report said it had commissioned its own “in-house” research on the “concepts of ‘climate-flation’ and ‘heat-flation’” to see Canadians take on the terms.

Predictably, the bid to try and convince Canadians that the rising costs of living was the result of so-called “climate change” did not go over well with those polled as nobody had even heard of the term “heat-flation.”

The information regarding the poll was gleaned from a report titled Continuous Qualitative Data Collection Of Canadians’ Views, as noted by Blacklock’s Reporter, and asked if Canadians had heard of these “terms before” with “none indicated they had.”

“Describing what they believed these terms referred to, many expected they were likely connected to the issue of climate change and rising economic costs of its effect as well as efforts to mitigate its impacts going forward,” noted the report.

“To clarify, participants were informed ‘heat-flation’ is when extreme heat caused by climate change makes food and other items more expensive, and that ‘climate-flation’ was a broader term that encompassed all of the ways in which climate change can cause prices to go up including but not limited to extreme heat.”

The report noted that while some of the people polled thought “climate change” might have had some effect on inflation, many other issues were seen as the cause.

The report noted that “All believed climate change was having at least some impact on the price of food” but not in the way the government narrative asserts.

The report found that some Canadians “felt that in addition to extreme heat and drought making it more difficult for farmers to protect their crops and livestock, extreme weather events could also cause damage to vital roadways and infrastructure making it more difficult to transport food products across the country. A few also expressed that in addition to impacting Canadian food production climate change could also make it more expensive to import food.”

Others, however, “expressed the opinion the federal government needed to reduce its spending, believing that growing deficits in recent years had contributed to rising inflation.”

Of note is that no Canadian government has balanced the budget since 2007, and many critics have pointed to this ever-increasing debt-load to the reason inflation has rocked the country.

When it came to the carbon tax, many expressed the view that the “carbon pricing system had served to further increase the rate of inflation.”

Whether its inflation, the carbon tax or other factors, it remains true that Canada’s poverty rate is on the rise.

As reported by LifeSiteNews, a July survey found that nearly half of Canadians are just $200 away from financial ruin as the costs of housing, food and other necessities has gone up massively since Trudeau took power in 2015.

Critics argue that instead of addressing these issues, the Trudeau government has instead used the “climate change” agenda to justify applying a punitive carbon tax on Canadians.

However, polls indicate that most Canadians are not as concerned with “climate change” as they are with other issues, and many do not buy into the alarmist government narrative. Many critics have also accused government officials of being hypocrites, as they punish Canadians via the carbon tax and other measures while themselves taking advantage of frequent flights at the expense of taxpayers.

Despite the rising unpopularity of such policies, the Trudeau government has continued to push a radical environmental agenda similar to those endorsed by globalist groups like the World Economic Forum and the United Nations.

Energy

The Trickster Politics of the Tanker Ban are Hiding a Much Bigger Reckoning for B.C.

From Energy Now

By Stewart Muir

For years, a conservation NGO supported by major foreign foundations has taken on the guise of Indigenous governance authority on British Columbia’s north coast. Meanwhile, rights-holding First Nations with an economic agenda are reshaping the region, yet their equal weight is overlooked. A clash of values has resulted.

For more than a decade, British Columbians have been told — mostly by well-meaning journalists and various pressure groups — that an organization called Coastal First Nations speaks with authority for the entire coast. The name sounds official. It sounds governmental. It sounds like a coalition of Indigenous governments with jurisdiction over marine waters.

It isn’t any of those things.

Coastal First Nations (CFN) is a non-governmental organization, incorporated under the BC Societies Act as The Great Bear Initiative Society. It doesn’t hold Indigenous rights or title. It has no legislated role to provide benefits or services to First Nations members. It has no jurisdiction over shipping, marine safety, forestry, fisheries, energy development, or environmental regulation. Yet its statements are frequently treated as if they carry the weight of sovereign authority.

It’s time to say out loud what many leaders — municipal, Indigenous, and industry — already know: CFN is an advocacy group, not a government. Case in point, a recent news story with the following lede: “B.C.’s Coastal First Nations say they will use ‘every tool in their toolbox’ to keep oil tankers out of the northern coastal waters.” A spokesperson claimed to represent “the Rights and Title Holders of the Central and North Coast and Haida Gwaii,” yet notwithstanding the rights of any individual First Nation, CFN does not hold any formal authority.

Here’s why this matters. The truth is, Alberta has already struck its grand bargain with the rest of Canada. Now it’s time to confront the uncomfortable truth that the country is still one bargain short of a functioning national deal.

In 2026, with Canadians increasingly alert to who is shaping national conversations, there is a reasonable expectation that debates affecting our economic future should be led and conducted by Canadians — not by foreign foundations, not by out-of-country campaign strategists, and not by NGOs built to advance someone else’s policy objectives.

Where the confusion came from

CFN’s rise in public visibility traces back to the “Great Bear Rainforest” era, when U.S. philanthropic foundations poured large sums of money into environmental campaigns in British Columbia. A Senate of Canada committee document notes that the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation alone provided approximately $25 million directly to Coastal First Nations, delivered as twenty-five nearly $1 million installments.

CFN also played a central role in the Great Bear Rainforest negotiations, which were financed by a coalition of foreign philanthropies including the Packard Foundation, Hewlett Foundation, Wilburforce Foundation, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Nature Conservancy/Nature United, and Tides Canada Foundation. These foundations collectively contributed tens of millions of dollars to the “conservation financing” model that anchored CFN’s operating environment.

This history isn’t speculative. It’s well documented in foundation reports, Canadian Parliamentary evidence, and the publicly disclosed financial architecture behind the Great Bear Rainforest. For a generation, well-funded U.S. environmental campaigns have worked to make Canadians afraid of their own shadow by seeding doubt, stoking paralysis, and teaching a resource nation to second-guess the very wealth that built it.

Between 2010 and 2018, an independent forensic accounting review by Deloitte Forensic (backed by the Alberta government) found that foreign foundations provided roughly $788.1 million in grants for Canadian environmental initiatives. The largest single category — by a wide margin — was marine-based initiatives, totalling $297.2 million. In Deloitte’s categorization, “marine-based” overwhelmingly refers to coastal campaigns: Great Bear Rainforest–related advocacy, anti-tanker/shipping activism, marine-use regulation campaigns, marine ecological programs, and other coastal political work.

Land-based initiatives were the second-largest category ($191 million), followed by wildlife preservation ($173 million).

The forensic review also showed that of the $427.2 million that physically entered Canada, 82% — approximately $350.3 million — was spent in British Columbia, with the dominant share directed specifically toward coastal and marine initiatives.

Taken together, these findings confirm that foreign-funded environmental activity in Canada has been geographically concentrated in British Columbia and thematically concentrated on the coast – exactly the domain where CFN has been positioned as a public-facing authority.

The real authority lies with the nations themselves

If British Columbians want to understand who truly governs the coast, they should look to the Indigenous governments that hold rights, title, citizens, and accountability — not NGOs that comment from the sidelines. That means not overlooking:

- Haisla Nation, leaders of Cedar LNG

- Nisga’a Nation, co-developers of Ksi Lisims LNG

- Gitxaala Nation, asserting legal and territorial authority

- Kitselas and Kitsumkalum, both shaping regional development

These governments are also coastal First Nations. They negotiate major economic partnerships, steward lands and waters, and make decisions grounded in their own legal orders. Moreover, representation is the key measure of accountability in a democracy: First Nations governing councils are elected by their members. The CFN is not elected. The nations are accountable to their own people — not to U.S. philanthropies or to the strategic objectives of foreign-backed environmental campaigns.

The Haisla Nation once belonged to CFN, but quit in protest in 2012 when the body opposed LNG. The Haisla council went on to fully embrace economic development via liquefied natural gas and own the upcoming Cedar LNG project.

Meanwhile, the central and northern coastal regions where CFN has opposed numerous economic opportunities continue to suffer the worst child poverty in British Columbia.

In the delicate politics of the region’s First Nations alliances, relationships are constantly in motion and governed by inviolable traditions of mutual respect. From these threads, it has to be said that the CFN’s strategy of weaving the appearance of unanimity is truly a fabrication. In point of fact, CFN represents just one half of the story. My data source tells the story, by drawing together the latest available economic and demographic information for 216 British Columbia First Nations:

- Status Indian residents of CFN communities on the north coast number 5,484, with a total membership near and far of 20,447.

- The pro-development group noted earlier numbers 5,505 living local out of a total membership of 16,830.

In other words, virtually equal. Hence it’s obvious that any media report citing CFN as the singular authority for local First Nations interests is a misleading one. CFN speaks for only a slice of the North Coast, not the whole, and the numbers make that impossible to ignore.

When a CFN motion opposing responsible resource development was adopted by the Assembly of First Nations (see Dec. 2 news), it was further evidence that the deck is stacked against First Nations that are accountable and position themselves as having broad responsibilities, including but not limited to raising the standard of living of their members.

The future belongs to the nations

The politics of LNG on the North Coast can’t be grasped without staring directly at the tanker ban — not as scripture, but as the political curiosity it has become. Anyone who knows these waters understands it’s mostly theatre: it doesn’t question letting Alaska oil tanker ships transit our exclusive economic zone when we cannot, and it doesn’t touch the real risks coastal people actually worry about. Yet waving it away is naïve. The ban behaves like a trickster spirit in our public life — capricious, emotionally loaded, and capable of turning a routine policy debate into a cultural conflagration with barely a flick of its tail.

This is why Coastal First Nations retain such gravitational pull. For years, the ban has served as the moral architecture of their Great Bear Sea campaign. CFN represents a long-game strategy — build legitimacy, occupy the moral high ground, and shape the destiny of a nation by holding the symbolic centre. Their concerns seem genuine and rooted in lived stewardship – yet were shaped by Madison Avenue minds hired by American philanthropists to affect our politics. But a near equal number of coastal nation residents unified by a different outlook also have skin in the game. They are charting futures grounded in prosperity, environmental care, and sovereignty on their own terms, and their authority is the real thing — born of title, law, and accountability to their own people.

And here is the irony worth heeding: the tanker ban’s pageantry masks a solution. It is dragging into daylight a conversation the province has avoided for decades — a conversation that will soon prove inevitable as court rulings unsettle the very foundation of property rights in British Columbia. This is the hinge that the moment turns on.

Canada cannot resolve its growing national contradictions without moving its energy to global markets. Alberta has already made its grand bargain with the country. Now British Columbia must craft its own — harnessing the prosperity of energy development to discharge political debts and finally settle the title question that has defined the province’s modern era.

Stewart Muir

Energy

A look inside the ‘floatel’ housing B.C.’s LNG workforce

From Resource Works

Innovative housing solution minimizes community impact while supporting the massive labour force needed for the Woodfibre LNG project.

The Woodfibre LNG project — a national leader in Indigenous partnerships and a cornerstone of global energy security — relies on a large construction workforce that drives economic prosperity across the region. For many of these workers, “home” is a ship.

Refitted from a cruise liner into a dedicated accommodation vessel, or “floatel,” this innovative solution houses up to 600 workers near Squamish, B.C., while keeping pressure off local housing and minimizing the project’s community footprint.

These exclusive images, captured a year ago, offer a rare retrospective look inside the original floatel. MV Isabelle X. With a second accommodation ship, the MV Saga X, recently arrived, this photo essay gives a timely, ground-level view of life aboard: individual cabins, a full-service dining hall, recreation spaces and custom laundry facilities. It’s a glimpse into the offshore dormitory that anchors daily life for the crew bringing this vital energy project to completion.

An arcade room is seen on a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

A dining area is seen on a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

A cabin is seen on a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

Bridgemans Services Group president Brian Grange stands at the stern on a renovated cruise ship known as a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

A custom built heat pump unit that allows the ship to avoid using diesel while docked and at anchor is seen on a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

The main entry and exit area for workers is seen on a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, during a media tour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

A renovated cruise ship known as a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, is seen at anchor in the harbour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

A tugboat and water taxi are seen docked at a renovated cruise ship known as a “floatel” that Woodfibre LNG plans to use to house 600 construction workers at a liquefied natural gas export facility being built near Squamish, at anchor in the harbour in Vancouver, on Thursday, May 9, 2024. The ship arrived in B.C. waters in January after a 40-day journey from Estonia, where it had sheltered Ukrainian refugees, but the District of Squamish council voted three to four against a one-year permit for its use last week.

All photos credited to THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Resource Works News

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Alberta2 days ago

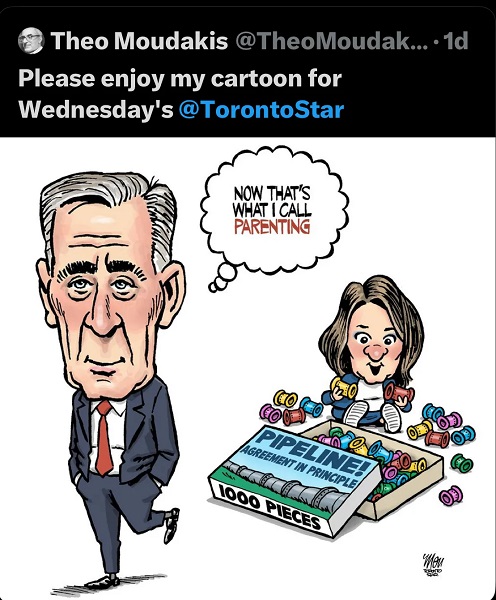

Alberta2 days agoCarney’s pipeline deal hits a wall in B.C.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Sports Hall of Fame Announces Class of 2026 Inductees

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis slams Liberal plan targeting religious exemption in hate speech bil

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoIs Carney Falling Into The Same Fiscal Traps As Trudeau?

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada’s climate agenda hit business hard but barely cut emissions

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoNews RFK Jr.’s vaccine committee to vote on ending Hepatitis B shot recommendation for newborns