I care about sea turtles, I really do. But as I poked that flimsy thing through the lid and took a sip, it was not sweet enjoyment I was experiencing. It was bitter disappointment. Almost immediately the straw started to soften and it soon collapsed upon itself. It was like trying to drink through a soaked napkin. Frustrated, I tossed the straw aside and drank straight from the cup, hoping that I wouldn’t end up with bright green latte all over my laptop or sweater. Yet another small indulgence ruined by Ottawa.

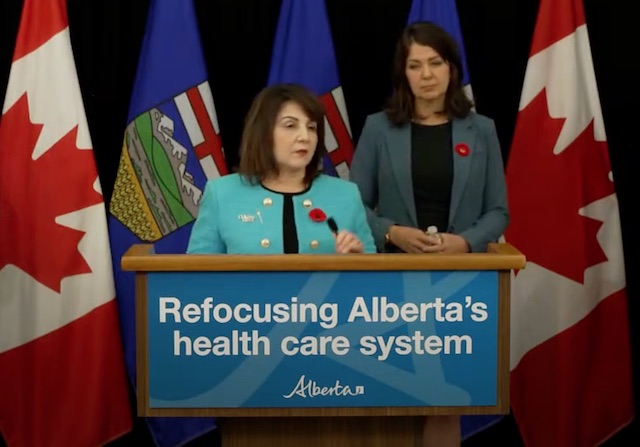

Small indulgences, ruined. Across the country, Canadians are growing frustrated with a single-use plastics ban that has given them useless paper straws and taken away useful items such as plastic bags. (Source of right photo: CTV News)

Small indulgences, ruined. Across the country, Canadians are growing frustrated with a single-use plastics ban that has given them useless paper straws and taken away useful items such as plastic bags. (Source of right photo: CTV News)

I’m not alone. Across the country Canadians are griping about dissolving cardboard straws, berating themselves for forgetting their reusable shopping bags (made of a much thicker and unrecyclable plastic) and wondering exactly how they’re supposed to eat their takeout meal without a fork. Life is stressful enough with inflation, rising public drug use, street protests, overseas wars and other major calamities. Now even the tiniest details of our lives – like enjoying a cold drink on a hot day – have been imperilled as well. And yet a soggy, useless straw is not just a lousy way to start your workday. It’s also another worrisome example of the Justin Trudeau government’s relentless intrusions into provincial and local jurisdictions.

There is hope, however. In November 2023, a Federal Court judge struck down the government’s regulatory efforts against certain plastic items as “unreasonable and unconstitutional”. The ban, however, continues to remain in force while Ottawa appeals that ruling. The appeal will be heard later this month; and the legal charity I work for, the Canadian Constitution Foundation (CCF), will be an intervenor because we think this is a very important case. At stake are the very foundations of Canada’s Constitution. And a chance to get some straws that actually work.

Canada’s Plastics Ban 101

It’s easy to understand the desire to reduce plastic waste. Images of masses of trash floating in the Pacific Ocean or videos of sea turtles and birds choked by ring-carriers and bags have a visceral impact on many people. We all want a clean environment that is safe for wildlife and humans alike.

Ottawa knows best: While many Canadian cities, including Edmonton (shown at left), were experimenting with various regulations for single-use plastics, the federal government usurped their jurisdiction by announcing a nation-wide ban on six common plastic items to take effect in 2022. At right, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau unveils the federal plastics ban at a press conference in Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Que., 2019. (Source of right photo: The Canadian Press/Paul Chiasson)

Ottawa knows best: While many Canadian cities, including Edmonton (shown at left), were experimenting with various regulations for single-use plastics, the federal government usurped their jurisdiction by announcing a nation-wide ban on six common plastic items to take effect in 2022. At right, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau unveils the federal plastics ban at a press conference in Mont-Saint-Hilaire, Que., 2019. (Source of right photo: The Canadian Press/Paul Chiasson)

And it is for these reasons that reducing plastic waste has been a policy goal for governments across Canada for many years. Numerous cities and towns have experimented with different approaches. Vancouver, Edmonton, Montreal and Guelph, for example, have all imposed some type of ban on what are termed “single-use” plastics. Toronto has not done so, but recently introduced a bylaw requiring businesses to ask customers if they’d like a single-use item and requiring them to accept reusable bags and cups. In early 2024, Calgary introduced a single-use plastic bylaw prohibiting businesses from giving customers single-use straws and food-ware unless they specifically asked, and requiring a 15¢ charge for single-use bags. Calgarians immediately went ballistic, however, forcing City Council to repeal the measure just weeks after coming into effect.

Despite these many diverse local innovations, in 2022 the federal government imposed its own vision on the country with a sweeping attempt to eradicate or severely curtail the use of six single-use plastic items: straws, cutlery, takeout containers, stir sticks, plastic bags and ring-carriers. These banned items would need to be replaced by substitutes made of other material, such as paper, wood, ceramic or metal.

As environmental policy, the federal plastics ban has some very large problems. As this C2C Journal article pointed out, Canadian plastic waste comprises a perishingly small share (0.02 percent to 0.03 percent) of total ocean plastic pollution. Almost all plastic waste in Canada is either recycled, incinerated or landfilled; it is not polluting the environment. The federal government’s own analysis also revealed that eliminating single-use plastics would actually increase overall waste generation rather than reduce it. While the goal is to remove approximately 1.6 million tonnes of plastic waste from 2023 to 2032, the amount of other waste streams is expected to grow by 3.2 million tonnes. This is because substitutes tend to be heavier than the plastic items they replace.

Sea turtles are safe with us: Despite widespread concern over the effect of plastic pollution on ocean life, the overwhelming majority of plastic garbage in Canada is either recycled, landfilled or incinerated; Canada’s share of plastic ocean pollution is estimated at between 0.02 percent and 0.03 percent. (Sources: (photo) Shutterstock; (chart) Greenpeace)

Sea turtles are safe with us: Despite widespread concern over the effect of plastic pollution on ocean life, the overwhelming majority of plastic garbage in Canada is either recycled, landfilled or incinerated; Canada’s share of plastic ocean pollution is estimated at between 0.02 percent and 0.03 percent. (Sources: (photo) Shutterstock; (chart) Greenpeace)

It gets worse. According to the government’s Strategic Environmental Assessment, substitutes for plastic products, such as paper bags, “typically have higher climate change impacts” including higher greenhouse gas emissions and a reduction in air quality. By banning plastic bags, straws and so on, we will end up with not only more garbage, but also a dirtier environment.

An Order-in-Council signed in April 2021 brazenly declared every product made from plastic to be a threat to human health. This includes everything from children’s toys, water pipes, health-care devices and protective helmets to car parts and computer keyboards.

The plastics ban fails on basic economics as well. A cost/benefit analysis prepared by the federal government puts the ten-year monetary benefits arising from a reduction in plastic garbage across Canada at $616 million. On the other side of the ledger, the costs – including the impact on businesses required to replace perfectly useful plastic items with lower-quality substitutes that are generally more expensive – comes in at $1.9 billion. By the federal government’s own reckoning, its policy thus entails a net loss of $1.3 billion. In sum, the plastics ban does nothing to reduce worldwide ocean pollution, creates twice as much garbage as it saves and imposes costs exceeding its benefits by a substantial margin. Based on these rational measures alone, we should bin the ban. But the biggest reason to oppose it is constitutional.

Ottawa Takes Charge

Waste management is a provincial matter which provinces typical delegate to municipalities. This process is working well, as evidenced by all the experimentation in plastic waste policies described above. Yet the Trudeau government desperately wanted to be seen as a leader on this issue. And to get around the fact Ottawa has no clear authority to do so, the Liberals had to get creative.

Their solution was to add all “plastic manufactured items” to the list of toxic substances maintained under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Thus an Order-in-Council signed in April 2021 brazenly declared all products made from plastic to be a threat to human health. This includes everything from children’s toys, water pipes, health-care devices and protective helmets to car parts and computer keyboards. Items that are indispensable to our daily lives instantly became “toxic” as the result of a single federal Cabinet order. The policy took effect at the end of 2022.

Toxic, every last one. As a result of a 2021 Order-in-Council, the entirety of “plastic manufactured items” – including everything from children’s toys to life-saving medical devices – was declared hazardous to human health under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. (Source of bottom photos: Pexels)

Toxic, every last one. As a result of a 2021 Order-in-Council, the entirety of “plastic manufactured items” – including everything from children’s toys to life-saving medical devices – was declared hazardous to human health under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. (Source of bottom photos: Pexels)

In response to this obvious absurdity, a group of plastic industry companies called the Responsible Plastic Use Coalition demanded a judicial review, arguing the federal order made no practical or scientific sense. Faced with the prospect of defending its decision to declare, among other things, a wide variety of life-saving and medically-necessary devices as officially toxic, the federal government claimed it only intended to restrict the use of plastics that posed a real risk to the environment. Despite categorizing all plastic as deadly, Ottawa said it was only looking to regulate the harmful bits, like straws and plastic bags. Bureaucrats, using the new authority granted them by Cabinet, would later decide which was which.

The federal government tried a similar line of argument when defending another piece of controversial environmental legislation, the Impact Assessment Act. This act purported to subject proposed new infrastructure projects to review across a vast range of economic, social, health, environmental and even gender-related impacts. The law was challenged in court by Alberta on the grounds that it intruded into provincial jurisdiction. In court, Ottawa argued that it only intended to regulate projects with environmental impacts of significant national concern. The Alberta Court of Appeal was unmoved by this attempted rationale, finding the Act unconstitutional, and last October a 5-2 majority of the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the lower court’s findings. Chief Justice Richard Wagner wrote for the majority that Parliament “plainly overstepped their constitutional competence” by purporting to regulate projects that would otherwise fall within provincial jurisdiction. The vast majority of the Act was found to be unconstitutional.

Calling out an absurdity: Responsible Plastic Use Coalition, an industry lobby group, challenged the Trudeau government’s declaration that all plastic is toxic in the Federal Court of Canada.

Calling out an absurdity: Responsible Plastic Use Coalition, an industry lobby group, challenged the Trudeau government’s declaration that all plastic is toxic in the Federal Court of Canada.

A similar thing happened with the plastics ban. In November 2023, Federal Court of Canada Justice Angela Furlanetto sided with the plastics coalition and struck down the law, calling the government’s sweeping attempt at banning plastics as “outside their authority.”

In her ruling, Justice Furlanetto shredded the government’s tortuous logic defining every form of plastic to be a threat to human health, observing that “plastic manufactured items” is far too broad a category to include on a list of toxic substances; the government provided no evidence to establish that every product listed was actually harmful. “The broad and all-encompassing nature of the category of [plastic manufactured items] poses a threat to the balance of federalism as it does not restrict regulation to only those [items] that truly have the potential to cause harm to the environment,” she wrote. She also noted that “for a chemical substance to be toxic it must be administered to an organism or enter the environment at a rate (or dose) that causes a high enough concentration to trigger a harmful effect. In this instance, the reverse logic appears to be applied…”

As Justice Furlanetto held in her 2023 Federal Court decision, ‘The machinery of criminal law cannot be used to assume control over something that is not within Parliament’s authority.’

Justice Furlanetto also held that the Cabinet order extended far beyond the federal government’s ability to regulate the environment through the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. As a result, she ordered the ban quashed and declared invalid and unlawful. Ottawa immediately appealed this ruling, with the case to be heard at the Federal Court of Appeal on June 24 and 25. Alberta and Saskatchewan are both intervenors and will argue that the Federal Court ruling should be upheld. British Columbia is intervening to support the federal government’s position that the order is within federal jurisdiction. There are other public interest interveners as well, including the CCF, EcoJustice, and Animal Justice.

The Bogus Fight Against Plastic Criminality

“Unreasonable and unconstitutional”: In her November 2023 ruling, Federal Court of Canada Justice Angela Furlanetto found that Ottawa overstepped its jurisdiction in classifying all plastic goods as toxic. Ottawa is now appealing her ruling. (Source of photo: @FedCourt_CAN_en/X)

“Unreasonable and unconstitutional”: In her November 2023 ruling, Federal Court of Canada Justice Angela Furlanetto found that Ottawa overstepped its jurisdiction in classifying all plastic goods as toxic. Ottawa is now appealing her ruling. (Source of photo: @FedCourt_CAN_en/X)

One of the main issues at the appeal will be the role of the federal government’s criminal law power. Section 91(27) of the Constitution Act grants the federal government exclusive authority to make criminal law. And previous court rulings have found and affirmed that prohibiting truly toxic substances, like lead and mercury, under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act is a legitimate expression of that power.

But it is no magic wand. Ottawa cannot simply claim a need to invoke its “criminal law power” and instantly transform any issue into an area it can regulate. As Justice Furlanetto held in her 2023 Federal Court decision, “The machinery of criminal law cannot be used to assume control over something that is not within Parliament’s authority.” In this case, criminal law power should not be allowed to justify the sweeping inclusion of every imaginable plastic product on the list of “toxic” substances and therefore place them all under the umbrella of federal authority. This is what lawyers call ultra vires – Latin for “outside the power”, in this case, of a government.

Criminal law powers should be applied cautiously. To claim authority to regulate something based on this authority, Parliament must clearly demonstrate the criminal aspect of the targeted activities. The federal government cannot assume control over an entire area which is not, in itself, harmful or dangerous. This is particularly important when Parliament has asserted control and jurisdiction over an amorphous subject matter prone to overlapping jurisdictions, like environmental regulation.

“Harm should be real”: According to University of Alberta law professor Eric Adams, the federal government’s criminal law power must only be used when there is a real threat of criminal behaviour. Fretting about plastic pollution does not meet such a test. (Source of photo: University of Alberta)

“Harm should be real”: According to University of Alberta law professor Eric Adams, the federal government’s criminal law power must only be used when there is a real threat of criminal behaviour. Fretting about plastic pollution does not meet such a test. (Source of photo: University of Alberta)

When the framers of Canada’s original Constitution in the 1860s decided that the federal government and not the provinces should control criminal law, this was premised on Parliament using its authority to prevent actual harm. University of Alberta law professor Eric Adams has written that criminal law power rests on the notion that “harm should be real in the sense that Parliament has a ‘rational basis’ for seeking to suppress it with prohibitions” and that it can be “demonstrated with evidence.” Accordingly, federal criminal law power must be focused, justified and rationally connected to a real criminal threat to the area in question, in this case the environment. Deeming every single imaginable plastic manufactured item “toxic” does not meet this test.

Hardly Incidental

The federal government will be defending the Cabinet order listing non-harmful plastics as toxic by arguing that any intrusion into provincial jurisdiction is merely “incidental” and not worth worrying about. There is, indeed, an aspect of Canadian constitutional law called the “incidental effects doctrine” which recognizes that it is practically impossible for one level of government to legislate without touching on the powers of another level of government in some way.

Negotiating the application of the incidental effects doctrine requires a flexible approach to federalism that permits collateral and secondary effects on another jurisdiction without threatening the main intent of the originating jurisdiction’s legislation. This concept was crystallized in the 2007 Supreme Court ruling in Canadian Western Bank v. Alberta that found Alberta was within its constitutional right to regulate the sale of insurance (a provincial responsibility) at banks in the province, even if the banking sector itself fell under federal jurisdiction.

Hardly incidental: Ottawa argues its intrusion into provincial jurisdiction over plastics is merely “incidental” and should be allowed to stand. In previous rulings, however, the courts have rejected such arguments when the outcome would make an “otherwise unconstitutional law valid”. In 2019, the B.C. Court of Appeal struck down a proposed B.C. law intended to stop the federally-regulated Trans Mountain pipeline (shown) on similar grounds. (Source of photo: Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Hardly incidental: Ottawa argues its intrusion into provincial jurisdiction over plastics is merely “incidental” and should be allowed to stand. In previous rulings, however, the courts have rejected such arguments when the outcome would make an “otherwise unconstitutional law valid”. In 2019, the B.C. Court of Appeal struck down a proposed B.C. law intended to stop the federally-regulated Trans Mountain pipeline (shown) on similar grounds. (Source of photo: Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

But such incidental effects cannot be limitless; they must indeed be incidental. Courts have repeatedly emphasized in other cases that a flexible approach to federalism must not “erode the constitutional balance” inherent in Canada’s division of powers and cannot make an “otherwise unconstitutional law valid”, as a 2019 B.C. Court of Appeal ruling stated in striking down a proposed B.C. law intended to stop the Trans Mountain pipeline, a federally-regulated endeavour. The classification of effects as incidental or consequential must be made with clarity and rigour.

The Trudeau government’s Cabinet order that all plastics are “toxic” clearly crosses the dividing line between incidental effects and intrusion into provincial jurisdiction. Plastic is ubiquitous in modern society and most matters requiring the regulation of plastic materials properly fall under provincial jurisdiction. By listing all imaginable types of plastics as toxic, without regard to whether they actually cause any harm, the federal government sought to greatly expand its jurisdiction across an exceedingly broad subject area. Like criminal law powers, the incidental effects doctrine should not be misused to cloak far-reaching legal effects from constitutional scrutiny.

The Bigger Threat

The brilliance of Canadian federalism is that it prevents the concentration of power within any single institution or level of government and creates laboratories of democracy across Canada where different jurisdictions can tailor different policy solutions and test what works best. Canada’s constitutional division of powers is thus a pathway to better policies that lead to a freer Canada. It also acts as a restraint on government overreach. It deserves to be protected.

But in numerous recent court cases and policies, the Trudeau government has demonstrated its extreme ambivalence – if not outright hostility – to Canada’s constitutional federal structure. In examples including the Greenhouse Gas Emission Pricing Act Reference, the Impact Assessment Act Reference and now the Cabinet order on plastics, the mechanism, if not the intent itself, is to grab additional authority from other levels of government in order to impose national policies that violate the founding structure of our country. This is why the plastics case has implications far beyond saving Canadians from soggy straws.

Ottawa would essentially become the master of all environmental policy in the country; and since so many other policy areas have an environmental dimension, the federal government could gradually come to rule them all.

The CCF will argue in the Federal Court of Appeal that federal environmental regulation poses a unique challenge to the division of powers, particularly where the purported federal target is submerged in a sea of local and provincial jurisdiction. Accordingly, federal statutes must be tightly focused on federal targets and not allowed to wander deeply into provincial jurisdiction.

If plastics of all kinds are confirmed as toxic substances, and Parliament is given authority to regulate them, this could trigger a whole host of other regulatory environmental mechanisms in the areas of licensing, regulation of substitutes and offset mechanisms that would further encroach on provincial jurisdiction. It is widely discussed, for example, that the federal government will seek to uphold its planned cap on oil and gas emissions, as well as its Clean Electricity Regulations (both currently in draft form) through similar listings under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. It would also likely use its criminal law power to get a foothold into the regulation of methane, carbon dioxide and other substances in order to control them in a detailed manner. And there is reasonable concern the federal government could also attempt to regulate things like electricity markets and other technologies under these newfound powers. Ottawa would essentially become the master of all environmental policy in the country; and since so many other policy areas have an environmental dimension, the federal government could gradually come to rule them all. The only thing necessary for each new intrusion will be for the Liberals – or some other future activist federal government – to whisper the magic phrases “criminal law power” and “incidental effects” and it becomes so.

Where will it end? According to the Canadian Constitution Foundation, allowing the federal government to get away with labelling all plastic products as toxic will inevitably encourage further intrusions into local and provincial jurisdiction, allowing Ottawa to set itself up as the master of all environmental policy. Shown, protesters gather outside the Federal Court in Toronto during the initial plastic-ban hearings in 2023. (Source of photo: Michael Cole/CBC)

Where will it end? According to the Canadian Constitution Foundation, allowing the federal government to get away with labelling all plastic products as toxic will inevitably encourage further intrusions into local and provincial jurisdiction, allowing Ottawa to set itself up as the master of all environmental policy. Shown, protesters gather outside the Federal Court in Toronto during the initial plastic-ban hearings in 2023. (Source of photo: Michael Cole/CBC)

If the division of powers under Canada’s Constitution means anything, the Federal Court of Appeal must find the Trudeau government’s plastics ban unconstitutional. My struggle to drink my straw-free iced latte is thus a small part of a much larger struggle for balance and respect in Canada’s foundational framework. I am slurping with purpose.

Christine Van Geyn is litigation director of the Canadian Constitution Foundation.

Impossible dream: With fossil fuels currently meeting 73 percent of Canada’s overall energy requirements and fulfilling critical needs from heating to medical services, getting to “net zero” emissions anytime soon seems delusional. (Sources of photos: (top two) Pexels; (bottom two) Unsplash)

Impossible dream: With fossil fuels currently meeting 73 percent of Canada’s overall energy requirements and fulfilling critical needs from heating to medical services, getting to “net zero” emissions anytime soon seems delusional. (Sources of photos: (top two) Pexels; (bottom two) Unsplash) “Axe the Tax” has its limits: Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre (top) has pledged to get rid of the hated consumer carbon tax and eliminate comprehensive electric vehicle mandates, but he’s expected to maintain the pricey “producer” carbon tax on industrial emitters. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Paul Daly; (middle)

“Axe the Tax” has its limits: Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre (top) has pledged to get rid of the hated consumer carbon tax and eliminate comprehensive electric vehicle mandates, but he’s expected to maintain the pricey “producer” carbon tax on industrial emitters. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Paul Daly; (middle)  A better way: Founded by Danish environmentalist Bjorn Lomborg, the Copenhagen Consensus Center uses rational economic analysis to advance global welfare in areas from battling disease to addressing climate change. (Source of left photo:

A better way: Founded by Danish environmentalist Bjorn Lomborg, the Copenhagen Consensus Center uses rational economic analysis to advance global welfare in areas from battling disease to addressing climate change. (Source of left photo:  “Arbitrary targets”: Applying Copenhagen Consensus rational analysis would mean abandoning or postponing Canada’s “Net-Zero by 2050” goal and focusing instead on practical environmental improvement projects. Shown at bottom, the Gold Bar Wastewater Treatment Plant in Edmonton, Alberta. (Sources of photos: (top) JessicaGirvan/Shutterstock; (bottom)

“Arbitrary targets”: Applying Copenhagen Consensus rational analysis would mean abandoning or postponing Canada’s “Net-Zero by 2050” goal and focusing instead on practical environmental improvement projects. Shown at bottom, the Gold Bar Wastewater Treatment Plant in Edmonton, Alberta. (Sources of photos: (top) JessicaGirvan/Shutterstock; (bottom)  The steep cost of compliance: The Justin Trudeau government’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan will add an estimated $55,000 to the average price of a new home, pointing to the need to eliminate costly and pointless regulation. (Source of photo:

The steep cost of compliance: The Justin Trudeau government’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan will add an estimated $55,000 to the average price of a new home, pointing to the need to eliminate costly and pointless regulation. (Source of photo:  A common-sense climate change policy would also streamline, limit the scope of and quicken the currently often 10-year-long environmental assessment process. Shown, the LNG Canada project in Kitimat, B.C. under construction, January 2024. (Source of screenshot:

A common-sense climate change policy would also streamline, limit the scope of and quicken the currently often 10-year-long environmental assessment process. Shown, the LNG Canada project in Kitimat, B.C. under construction, January 2024. (Source of screenshot:  Focus on harmony: To promote more efficient cross-border trade, Canada’s regulatory standards should align with those of the U.S. The incoming Donald Trump Administration is likely to discard electric vehicle mandates and “clean” fuel standards, policy shifts that will affect Canada. (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Evan Vucc; (bottom) Sundry Photography/Shutterstock)

Focus on harmony: To promote more efficient cross-border trade, Canada’s regulatory standards should align with those of the U.S. The incoming Donald Trump Administration is likely to discard electric vehicle mandates and “clean” fuel standards, policy shifts that will affect Canada. (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Evan Vucc; (bottom) Sundry Photography/Shutterstock) A new climate change policy should include measures to increase the resilience of Canadian infrastructure and the economy to future climate changes. Shown, (at top) a storm in coastal Nova Scotia; (at bottom) flooding in B.C.’s Lower Mainland. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Andrew Vaughan; (bottom) The Canadian Press/Jonathan Hayward)

A new climate change policy should include measures to increase the resilience of Canadian infrastructure and the economy to future climate changes. Shown, (at top) a storm in coastal Nova Scotia; (at bottom) flooding in B.C.’s Lower Mainland. (Sources of photos: (top) The Canadian Press/Andrew Vaughan; (bottom) The Canadian Press/Jonathan Hayward)

To your health: The “J-Curve” plots the well-documented relationship between moderate social drinking and a long lifespan, revealing the healthiest level to be around one drink per day, what the new CCSA standards call “high risk”.

To your health: The “J-Curve” plots the well-documented relationship between moderate social drinking and a long lifespan, revealing the healthiest level to be around one drink per day, what the new CCSA standards call “high risk”. “The opposite of good public health advice”: According to Dan Malleck, chair of Brock University’s Department of Health Sciences, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction’s (CCSA) 2023 guidelines suggesting alcohol in any amount is a health hazard are unrealistic. (Source of photo:

“The opposite of good public health advice”: According to Dan Malleck, chair of Brock University’s Department of Health Sciences, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction’s (CCSA) 2023 guidelines suggesting alcohol in any amount is a health hazard are unrealistic. (Source of photo:  Too strict even for the Liberals: Federal Mental Health and Addictions Minister Ya’ara Saks has chosen not to adopt the CCSA’s 2023 drinking guidelines as official policy – yet Statistics Canada insists on using them to measure Canadians’ drinking habits. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld)

Too strict even for the Liberals: Federal Mental Health and Addictions Minister Ya’ara Saks has chosen not to adopt the CCSA’s 2023 drinking guidelines as official policy – yet Statistics Canada insists on using them to measure Canadians’ drinking habits. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld)

Canada’s native community has struggled with alcohol abuse ever since white settlement began. Many federal policies have attempted to address this, including the creation of Canada’s North West Mounted Police (NWMP) in 1873. Shown, NWMP officer with members of the Blackfoot First Nation outside Fort Calgary, 1878.

Canada’s native community has struggled with alcohol abuse ever since white settlement began. Many federal policies have attempted to address this, including the creation of Canada’s North West Mounted Police (NWMP) in 1873. Shown, NWMP officer with members of the Blackfoot First Nation outside Fort Calgary, 1878. Habs fans at work: While Statcan appears unwilling to publish data revealing that Indigenous Canadians are among the biggest drinkers in Canada, it has no such qualms about identifying Quebec as Canada’s thirstiest province. (Source of photo:

Habs fans at work: While Statcan appears unwilling to publish data revealing that Indigenous Canadians are among the biggest drinkers in Canada, it has no such qualms about identifying Quebec as Canada’s thirstiest province. (Source of photo:  Ottawa’s $172 million Disaggregated Data Action Plan (DDAP), unveiled in 2021, is meant to collect and distribute more detailed data on targeted groups including women, Indigenous people and the disabled. It doesn’t always work as promised.

Ottawa’s $172 million Disaggregated Data Action Plan (DDAP), unveiled in 2021, is meant to collect and distribute more detailed data on targeted groups including women, Indigenous people and the disabled. It doesn’t always work as promised. Anti-scientific: As a result of the DDAP, Statcan now randomly distributes responses from people who self-identify as transgender or non-binary into its Men+ and Women+ categories, making a mockery of good statistical practice. (Source of photo: Shutterstock)

Anti-scientific: As a result of the DDAP, Statcan now randomly distributes responses from people who self-identify as transgender or non-binary into its Men+ and Women+ categories, making a mockery of good statistical practice. (Source of photo: Shutterstock) This party can’t last forever: Statcan’s recent survey on Canadians’ drinking habits reveals the many ways in which the statistical agency is becoming increasingly ideological in how it collects (and hides) data. If left unchecked, this will eventually lead to its irrelevance as a source of reliable information. (Source of photo:

This party can’t last forever: Statcan’s recent survey on Canadians’ drinking habits reveals the many ways in which the statistical agency is becoming increasingly ideological in how it collects (and hides) data. If left unchecked, this will eventually lead to its irrelevance as a source of reliable information. (Source of photo: