Indigenous

There are no Indian Residential School denialists, so why criminalize them?

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Rodney A. Clifton, professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. (He was a former Senior Boys’ Supervisor in Stringer Hall, the Anglican residence in Inuvik.)

” both sides agree that Indian Residential Schools existed, and that some children were harmed. But they disagree on the evidence needed to prove whether children were murdered and buried unceremoniously in residential schoolyards. “

In a recent Canadian Press story, Kimberly Murray, the government’s special interlocutor on unmarked graves of missing Indigenous children from residential schools, is reported as saying: “We could … make it an offense to incite hate and promote hate against Indigenous people by … denying that residential (schools) happened or downplaying what happened in the institutions.” Not surprisingly, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is sympathetic to the special interlocutor’s call to action.

Ms. Murray says that Indigenous leaders across the country support her call for legislation. The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), for example, asked the Justice Minister, Arif Virani, to amend the criminal code to criminalize denialism. AMC Grand Chief Cathy Merrick said that enacting such a law would provide “an opportunity for Canada to demonstrate an honest commitment to reconciliation…. to deny the existence of these institutions is a form of violence.”

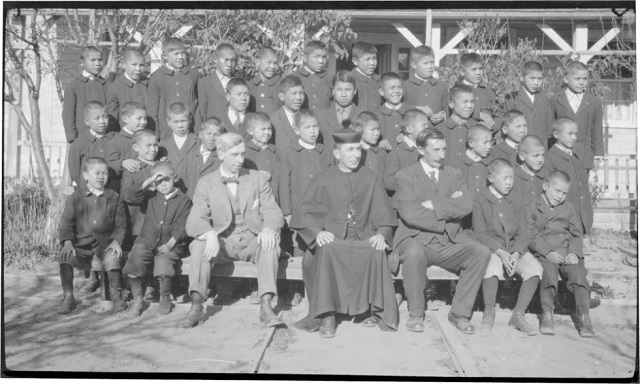

The focus on missing and murdered Indigenous children at residential schools became a national disgrace at the end of May 2021 when the Kamloops First Nation announced that stories from Knowledge Keepers and evidence from ground-penetrating radar (GPR) had “discovered” the graves of 215 children in the schoolyard of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Since that announcement, first nations across the country have discovered many more “graves,” also relying on Knowledge Keepers stories and GPR evidence. But so far, no bodies of IRS students have been exhumed from the schoolyards, even though the Chief TRC Commissioner, Justice Murry Sinclair, told CBC Radio host Matt Galloway a couple of years ago that as many as 15,000 to 25,000 Indian Residential School students are missing.

Surprisingly, these claims are not included in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Report. In fact, only one story of a murdered child is reported in the TRC Report, and it is the unverified story told by Doris Young about seeing a child’s murder at the Anglican Elkhorn Indian Residential School in Manitoba. The Commission reported this alleged murder but did not investigate the claim. Indeed, the Commission spent $60 million over six years and did not report any evidence, other than the Doris Young’s claim, of the murder of Indigenous children at residential schools.

What does this mean for criminalizing denialism?

There are at least three problems with potential legislation to criminalize denialism. First, Canada already has legislation on hate speech, and so new legislation is unnecessary.

Second, the definition of “denialism,” as reported above, is so vague that it would be almost impossible to convict anyone.

Finally, and most importantly, from what can be gathered from both Ms. Murray’s interim report and recent news items, practically no Canadians deny that Indian Residential Schools existed or that some children were harmed at those schools.

What Canadians seem to disagree on is the evidence that is needed to prove that IRS students were murdered, and their bodies were unceremoniously buried in unmarked graves in residential schoolyards.

On Ms. Murray’s side, supporters’ reason that “hear-say” evidence from Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and shadows on GPR screens are adequate to prove the claim. On the other side, the so-called “deniers” reason that forensic evidence from exhumed bodies is needed.

So, both sides agree that Indian Residential Schools existed, and that some children were harmed. But they disagree on the evidence needed to prove whether children were murdered and buried unceremoniously in residential schoolyards.

The Canadian law enforcement and justice system is the proper agency for an impartial investigation of this claim, and if evidence is obtained, to criminally charge those Indigenous and non-Indigenous IRS employees responsible and to report their names and crimes if they are deceased.

Surely Canadians would support such an impartial investigation leading to possible criminal charges. Till that happens, there is no reason to demonize the so-called “deniers” by those who disagree with the evidence they think is necessary to answer this important question. Without an independent investigation along with a public report, Canada cannot reach a fair and just reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

Indeed, many people are wondering why such a rigorous, systematic, investigation has not yet been conducted. It is the time to settle this issue so that both sides—indeed all Canadians—can move on from being pitted against each other over an issue that can be easily resolved with an independent investigation by competent justice officials.

Rodney A. Clifton is a is a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. He lived for four months in Old Sun, the Anglican Residential School on the Blackfoot (Siksika) First Nation, and was the Senior Boys’ Supervisor in Stringer Hall, the Anglican residence in Inuvik. Rodney Clifton and Mard DeWolf are the editors of From Truth Comes Reconciliation: An Assessment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (Frontier Centre for Public Policy, 2021). A second and expanded edition of this book will be published in 2024.

Business

Storm clouds of uncertainty as BC courts deal another blow to industry and investment

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Jason Clemens

Recent court decision adds to growing uncertainty in B.C.

A recent decision by the B.C. Court of Appeal further clouds private property rights and undermines investment in the province. Specifically, the court determined British Columbia’s mineral claims system did not follow the province’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA), which incorporated the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into law.

DRIPA (2019) requires the B.C. provincial government to “take all measures necessary to ensure the laws of British Columbia are consistent with the Declaration,” meaning that all legislation in B.C. must conform to the principles outlined in the UNDRIP, which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.” The court’s ruling that the provincial government is not abiding by its own legislation (DRIPA) is the latest hit for the province in terms of ongoing uncertainty regarding property rights across the province, which will impose massive economic costs on all British Columbians until it’s resolved.

Consider the Cowichan First Nations legal case. The B.C. Supreme Court recently granted Aboriginal title to over 800 acres of land in Richmond valued at $2.5 billion, and where such aboriginal title is determined to exist, the court ruled that it is “prior and senior right” to other property interests. Put simply, the case puts private property at risk in BC.

The Eby government is appealing the case, yet it’s simultaneously negotiating bilateral agreements that similarly give First Nations priority rights over land swaths in B.C.

Consider Haida Gwaii, an archipelago on Canada’s west coast where around 5,000 people live—half of which are non-Haida. In April 2024, the Eby government granted Haida Aboriginal title over the land as part of a bilateral agreement. And while the agreement says private property must be honoured, private property rights are incompatible with communal Aboriginal title and it’s unclear how this conflict will be resolved.

Moreover, the Eby government attempted to pass legislation that effectively gives First Nations veto power over public land use in B.C. in 2024. While the legislation was rescinded after significant public backlash, the Eby’s government’s continued bilateral negotiations and proposed changes to other laws indicate it’s supportive of the general move towards Aboriginal title over significant parts of the province.

UNDRIP was adopted by the United Nations in 2007 and the B.C. Legislature adopted DRIPA in 2019. DRIPA requires that the government must secure “free, prior and informed consent” before approving projects on claimed land. Premier Eby is directly tied to DRIPA since he was the attorney general and actually drafted the interpretation memo.

The recent case centres around mineral exploration. Two First Nations groups—the Gitxaala Nation and the Ehattesaht First Nation—claimed the duty to consult was not adequately met and that granting mineral claims in their land “harms their cultural, spiritual, economic, and governance rights over their traditional territories,” which is inconsistent with DRIPA.

According to a 2024 survey of mining executives, more uncertainty is the last thing B.C. needs. Indeed, 76 per cent of respondents for B.C. said uncertainty around protected land and disputed land claims deters investment compared to only 29 per cent and 44 per cent (respectively) for Saskatchewan.

This series of developments have and will continue to fuel uncertainty in B.C. Who would move to or invest in B.C. when their private property, business, and investment is potentially at risk?

It’s no wonder British Columbians are leaving the province in droves. According to the B.C. Business Council, nearly 70,000 residents left B.C. for other parts of Canada last year. Similarly, business investment (inflation-adjusted) fell by nearly 5 per cent last year, exports and housing starts were down, and living standards in the province (as measured by per-person GDP) contracted in both 2023 and 2024.

B.C.’s recent developments will only worsen uncertainty in the province, deterring investment and leading to stagnant or even declining living standards for British Columbians. The Eby government should do its part to reaffirm private property rights, rather than continue fuelling uncertainty.

C2C Journal

Wisdom of Our Elders: The Contempt for Memory in Canadian Indigenous Policy

By Peter Best

What do children owe their parents? Love, honour and respect are a good start. But what about parents who were once political figures – does the younger generation owe a duty of care to the beliefs of their forebears?

Two recent cases in Canada highlight the inter-generational conflict at play in Canada over Indigenous politics. One concerns Prime Minister Mark Carney and his father Robert. The other, a recent book on the life of noted aboriginal thinker William Wuttunee edited by his daughter Wanda. In each case, the current generation has let its ancestors down – and left all of Canada worse off.

William Wuttunee was born in 1928 in a one-room log cabin on a reserve in Saskatchewan, where he endured a childhood of poverty and hardship. Education was his release, and he went on to become the first aboriginal to practice law in Western Canada; he also served as the inaugural president of the National Indian Council in 1961.

Wuttunee rose to prominence with his controversial 1971 book Ruffled Feathers, that argued for an end to Canadian’s Indian Reserve system, which he believed trapped his people in poverty and despair. He dreamed of a Canada where Indigenous people lived side-by-side all other Canadians and enjoyed the same rights and benefits.

Such an argument for true racial equality put Wuttunee at odds with the illiberal elite of Canada’s native community, who still believe in a segregated, race-based relationship between Indigenous people and the rest of Canada. For telling truth to power, Wuttunee was ostracized from the native political community and banned from his own reserve. He died in 2015.

This year, William’s daughter Wanda had the opportunity to rectify the past mistreatment of her father. In the new book Still Ruffling Feathers – Let Us Put Our Minds Together, Wanda, an academic at the University of Manitoba, and several other contributors claim to “fearlessly engage” with her father’s ideas. Unfortunately, the authors mostly seek to bury, rather than

praise, Wuttunee’s vision of one Canada for all.

Wanda claims her father’s desire for a treaty-free, reserve-free Canada would be problematic today because it would have required giving up all the financial and legal goodies that have since been showered upon Indigenous groups. But there is a counterfactual to consider. What if Indigenous Canadians had simply enjoyed the same incremental gains in income, health and other social indicators as the rest of the country during this time?

Ample evidence on the massive and longstanding gap between native and non-native Canadians across a wide variety of socio-economic indicators suggest that integration would have been the better bet. The life expectancy for Indigenous Albertans, for example, is a shocking 19 years shorter than for a non-native Albertans. William Wuttunee was right all along about the damage done by the reserve system. And yet nearly all of the contributors to Wanda’s new book refuse to admit this fact.

The other current example concerns Robert Carney, who had a long and distinguished career in aboriginal education. When the future prime minister was a young boy, Robert was the principal of a Catholic day school in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories; he later became a government administrator and a professor of education. What he experienced throughout his

lifetime led the elder Carney to become an outspoken defender of Canada’s now-controversial residential schools.

When the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) attacked the legacy of residential schools, Carney penned a sharp critique. He pointed out that the schools were not jails despite frequent claims that students were there against their will; in fact, parents had to sign an application form to enroll their children in a residential school. Carney also bristled at

the lack of context in the RCAP report, noting that the schools performed a key social welfare function in caring for “sick, dying, abandoned and orphaned children.”

In the midst of the 2025 federal election campaign, Mark Carney was asked if he agreed with his father’s positive take on residential schools. “I love my father, but I don’t share those views,” he answered. Some Indigenous activists have subsequently accused Robert Carney of residential school “denialism” and “complicity” in the alleged horrors of Canada’s colonial education system.

Like Wanda Wuttunee, Mark Carney let his father down by distancing himself from his legacy for reasons of political expediency. He had an opportunity to offer Canadians a courageous and fact-based perspective on a subject of great current public interest by drawing upon his intimate connection with an expert in the field. Instead, Mark Carney caved to the

requirements of groupthink. As a result, his father now stands accused of complicity in a phony genocide.

As for William Wuttunee, he wanted all Canadians – native and non-native alike – to be free from political constraints. He rejected racial segregation, discrimination and identity politics in all forms. And yet in “honouring” his life’s work, his daughter misrepresents his legacy by sidestepping the core truths of his central belief.

No one doubts that Wanda Wuttunee and Mark Carney each loved their dads, as any son or daughter should. And there is no requirement that a younger generation must accept without question whatever their parents thought. But in the case of Wuttunee and Carney, both offspring have deliberately chosen to tarnish their fathers’ legacies in obedience to a poisonous

ideology that promotes the entirely un-Canadian ideal of permanent racial segregation and inequity. And all of Canada is the poorer for it.

Peter Best is a retired lawyer living in Sudbury, Ontario. The original, longer version of this story first appeared in C2CJournal.ca.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

Focal Points20 hours ago

Focal Points20 hours agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoThe day the ‘King of rock ‘n’ roll saved the Arizona memorial

-

Automotive10 hours ago

Automotive10 hours agoThe $50 Billion Question: EVs Never Delivered What Ottawa Promised

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoCanada’s air quality among the best in the world

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

-

Health18 hours ago

Health18 hours agoThe Data That Doesn’t Exist