Alberta

IN CASE OF EMERGENCY, READ THIS! Alberta’s COVID-19 Report

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Barry Cooper

The report calls for emergency management experts – not doctors or health care bureaucrats – to be in charge when such disasters strike, with politicians who are accountable to the people making the key decisions. Most important, the report demands much stronger protection for the individual freedoms that panic-stricken governments and overbearing professional organizations so readily quashed.

Nobody needs reminding that the Covid-19 pandemic – and the official responses to it – left hardly a person, group or country unaffected. From the lost learning of school closures to the crushed businesses and ruined lives, to the recurring social separation, to the physical toll itself, the wreckage came to resemble recession, social disintegration, war and the ravages of disease all in one. Yet the governments and organizations that designed and oversaw the emergency’s “management” have proved decidedly incurious about delving into whether they actually did a good job of it: what went right, what went wrong, who was responsible for which concepts and policies, who told the truth and who didn’t, and what might be done better next time. Few countries are performing any such formal evaluation (the UK and Sweden being prominent exceptions).

In Canada, the Justin Trudeau government has rebuffed calls for a public inquiry (perhaps a small mercy, as it is hard to envision this prime minister not politicizing such an exercise). Nearly every Canadian province is also ignoring the matter. The sole exception is Alberta, which in January created the Public Health Emergencies Governance Review Panel to, as its terms of reference state, “review the legislation and governance practices typically used by the Government of Alberta during the management of public health emergencies and other emergencies to recommend changes which, in the view of the Panel, are necessary to improve the Government of Alberta’s response to future emergencies.” The Panel’s inquiry fulfilled a promise made by Premier Danielle Smith when she was running for the leadership of the United Conservative Party.

These terms of reference need to be understood because they greatly influenced what followed – both the restrictions on the Review Panel’s inquiries and the broad scope of its recommendations, released in a densely written Final Report (367 pages including appendices) on November 15. The Panel was chaired by Preston Manning, Leader of the Official Opposition in Ottawa some 25 years ago but who more recently became a prominent voice of skepticism regarding the pandemic response, particularly the dismissive treatment of Canadians’ rights and liberties. With this report Manning has driven and led not one but two major pandemic-related reviews, as he was also central in the non-governmental National Citizens Inquiry on Canada’s Response to the Pandemic, which heard wrenching personal testimony.

Despite working under limitations, Manning and his colleagues have rendered valuable and, indeed, unparalleled public services with each effort. Here one must note whom Manning requested for Alberta’s Review Panel. They are in alphabetical order: Martha Fulford, an academic pediatrician at McMaster University with numerous scholarly articles to her credit; Michel Kelly-Gagnon, a businessman and President Emeritus of the Montreal Economic Institute; John C. Major, a former Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada; Jack Mintz, arguably Canada’s most distinguished living economist; and Rob Tanguay, a Calgary-based clinical psychiatrist specializing in treating addiction, depression and pain. Additional specialists prepared several of the report’s 11 appendices.

This is important because the response of Alberta’s NDP and its left-wing media helpers has been to accuse the Panel of mongering conspiracy theories and attempting to legitimize quack pseudo-science. They are using Manning, the founder and longtime leader of the Reform Party of Canada, as a convenient whipping boy. But they are effectively calling the entire panel – including a former member of the nation’s highest court who stood out for his calm and measured approach – a bunch of nutters if not worse. These critics seem to have emitted not one positive thought about any aspect of the Panel Report. That tells you a great deal about them, including that they probably didn’t even read it.

The report also prompted some balanced to favourable coverage, including from several journalists who previously were pro-lockdown, pro-masking and/or pro-vaccine. Edmonton Sun columnist Lorne Gunter, for example, termed the report “sensible and moderate,” noting that it calls for following “all of the credible science.” Gunter’s use of “all” is significant for, he notes, “a lot of what was pitched to the public as definitive scientific knowledge, such as the vitalness of mask and vaccine mandates, school closures, event cancellations and lockdowns was questioned by solid, reputable scientists (not just streetcorner anti-vaxxers and ‘I did my own research’ social-media experts).” Calgary Herald columnist Don Braid, a habitual UCP critic, also sounded impressed.

Alberta had a thoroughly designed, tested and previously deployed emergency plan. It just chose not to use it against Covid-19. This bizarre and gravely damaging decision has still not been explained.

So what is actually in the report? Chapter 1’s review of the Panel’s purpose notes it was set up to review the procedures Alberta has to respond to “any public emergency, including a public health emergency,” and how its preparations could be improved, including by broadening and deepening “the role of science in coping with future emergencies.” Its purpose was not to criticize Alberta’s actual responses to the Covid-19 event. While the Covid-19 public health emergency was the initial reason the panel was established, its recommendations would apply more broadly. And while science should be considered central to good public policy, science should not be regarded as consisting of a single narrative. Accordingly, “alternative perspectives” (Report, p. 5) should also be considered.

Alberta Emergency Management Agency

The spring 2020 spectacle of wildly shifting statements from public health officials and political leaders, its blizzard of decrees and edicts, proliferating “mandates,” haphazard changes of direction, imposition of seemingly arbitrary rules, public chaos, and sheer aura of panic – sweat-drenched faces, bulging eyes – might lead any citizen to believe that governments had never planned for or faced an emergency. The promiscuous use of “unprecedented” to describe Covid-19 only added to this feeling. In fact, Alberta had a thoroughly designed, tested and previously deployed emergency plan. It just chose not to use it against Covid-19. This bizarre and gravely damaging decision has still not been explained.

The Final Report’s largely overlooked Chapter 2 discusses improvements to the Alberta Emergency Management Agency (AEMA), making it important on several levels. The Panel recommends AEMA be adequately funded and remain the lead agency in dealing with any future emergency, including any future medical emergency. This alone is huge and hugely welcome. To ensure that individuals who are capable of dealing with emergencies and not just apprehended medical crises are in fact in charge, the Panel recommends several legislative changes to the Emergency Management Act and Public Health Act. Even better.

This sound recommendation rests upon the distinction between emergency management and normal policy decisions made by bureaucrats. The original Alberta emergency plan was developed in 2005 to deal with an anticipated influenza pandemic, and was in turn based on planning initiated across North America following the 9/11 terror atrocity. Alberta’s plan was similar to the approach followed by Sweden in 2020, which despite widespread initial condemnation proved highly successful. Its essential feature was that it was written and was to be implemented by individuals who specialize in emergencies, not by individuals with alleged expertise in the specific attributes of an anticipated emergency such as influenza or Covid-19, what the Panel on page 25 refers to as “subject-matter experts” (a more extensive quote is below).

By way of analogy, societies well-prepared to deal with emergencies do not put a limnologist in charge of an emergency response when riverbanks are unexpectedly breached and cause catastrophic flooding. Nor do they scramble to place a vulcanologist in charge when a volcano erupts and threatens lives and livelihoods. The purpose of putting highly trained emergency professionals in the lead during difficult situations is to remove as much as possible the shock effect from the surprises that emergencies typically bring, especially to normal politicians and conventional bureaucrats who expect normalcy to last forever and who panic when it doesn’t.

The emergency plan Alberta had going into 2020 was designed by David Redman, a former senior Canadian Forces officer whose 27 years of service included combat experience, a vocation that typically deals with unexpected surprises. The problem as the pandemic began was not in any lacunae that the Alberta emergency plan may have contained. Rather, as Redman, who at the time was director of Community Programs for Emergency Management (i.e., coordinating local responses), told C2C Journal in an interview in late 2020, “Governments took every plan they had ever written and threw them all out the window. No one followed the process. [The politicians] panicked, put the doctors in charge, and hid for three months.”

Redman was also emphatic on the question of fear, which is inevitably transmitted by panicked officials. He spent countless hours during the pandemic trying to warn every Canadian premier and many federal politicians that discarding emergency management principles and giving healthcare bureaucrats unprecedented authority was dangerous and would likely lead to disaster. Specifically, he urged healthcare officials and politicians to avoid expressing fear. Instead, he sadly noted in an interview with the Western Standard last week, “They used fear as a weapon. In emergency management you never use fear. You use confidence. You show confidence that the emergency can be handled and present a plan to show how this will be achieved.”

The Government of Alberta made a catastrophic and, as said, never-explained mistake when it turned the province over to a narrowly focused, unimaginative career bureaucrat credentialed only with an M.D. To be fair, this was probably too much for any one person, and Chief Medical Officer of Health Deena Hinshaw was placed in a near-impossible position. The consequences of this decision led to the removal of Premier Jason Kenney, and it is also why nearly the first thing his successor did was fire Hinshaw. That is also why the Manning Panel was commissioned.

So let us agree that the Panel’s recommendations to strengthen AEMA would improve emergency management the next time it is needed. That said, the Panel ignored the fact (or at least declined to state) that, had existing procedures been followed in 2020, things would have turned out much better.

Making Proper Use of Science – and Avoiding the Dictatorship of “Experts”

Chapter 3 deals with the place of “science” in public policy. It was self-evident to the Panel that science could help fashion sound public policy responses but could also be used for “political expedience and ideology.” Here the Panel was half-right. On the one hand it advanced a notion of “the scientific method” that dominated science classes a couple of generations ago. According to this account, a researcher develops testable hypotheses that can be modified in light of experimental results. Such was the philosophy of science that I was taught in grade 7 physics.

Its great defect is that it takes no account of what we now call conflicting paradigms or of what German Enlightenment-era philosopher Immanuel Kant called the power of judgment. A pandemic, for example, is not a “fact” but the product of somebody’s judgement. On the other hand, the Panel showed great clarity in asserting that “science is open to the consideration and investigation of alternative hypotheses…and is subject to some degree of uncertainty as an ever-present characteristic of scientific deliberations.” (Report, p. 24)

Before considering how it elaborated the problems of conflicting and alternative hypotheses and of uncertainty, one should note how opponents to both the Panel and UCP government responded to its commonsensical observations. According to NDP Leader Rachel Notley, they were “incredibly irresponsible.” Indeed, she asserted, “What you see is an invitation to normalize conspiracy theories and pseudo-science at the expense of evidence-based medical care.” Notley and CTV went on to attack Premier Smith for embracing “fringe views” – including those found in the October 2020 Great Barrington Declaration, a document written by three of the world’s most respected epidemiologists and subsequently endorsed by, at last count, 939,000 fellow scientists.

One of the Panel-endorsed “fringe views” was that “the number one priority” when a pandemic event is declared should be “protection of the most vulnerable,” (Report, p. 25) which is to say not everybody. Should a particular pandemic’s impact subsequently spread to other social, political and economic relationships, this priority may be modified and adjusted. That sounds eminently responsible, but the NDP wants everybody locked down right from the start.

Still the real question is: who would order the adjustments? The Panel’s answer is forthright, much to the consternation of scientific “experts”: “That a clear and conscious decision be made by elected officials as to the scope of the scientific advice to be sought and that this decision not be left entirely to the subject-matter agency, given that it may have a narrower perspective than that actually required.” (Report, p. 25, emphasis added) As Manning later said: “Political people have to be responsible for the overall direction and management because they’re the people that the public can hold accountable.”

Manning’s determination to avoid having a democracy become a dictatorship of “experts” also reflects a critical aspect of pandemic response: that there are issues far beyond medicine in play, and that the associated decisions are not scientific ones. Weighing risks, for example, is an exercise in logic (a branch of philosophy) and judgment, which depends on inductive reasoning. Assessing costs and benefits of various possible actions is economic in nature. And then, deciding just how much risk to take on and what costs to bear in the pursuit of benefits are questions of ethics. Such things should be undertaken by politicians because, if the people as a whole have a different view of such matters, they can vote in a different government (or, as happened in Alberta, select a decidedly different leader from the same party).

To the experts and their spokespersons, this was an anathema. Lorian Hardcastle, an associate professor in the University of Calgary’s law school and medical school, warned: “We would see ideologically driven response to a public health emergency” that would make it difficult “to keep people alive.” We can characterize the Hardcastle position, which was endorsed strongly during the pandemic by legacy media, the NDP, the “expert” class and the health care bureaucracy, as the “orthodox” doctrine. A health care emergency must be left to the so-called health care experts. Everyone else (including presidents, prime ministers and premiers) should defer to their expertise and do as they are told. The public “conversation” is entirely one-way.

In reality, however, public health does not involve just a single disease but all aspects of the health of a population. Thus, focussing on illness stemming from the SARS-CoV-2 virus was not enough even for so-called specialists because such a focus meant that, for instance, cancer screening was postponed so hospitals would be empty enough to accept the (incorrectly) projected tsunami of Covid-19 patients. Yet cancer is also part of public health, as was the collateral damage from the economic and social effects of lockdowns, school closures and social distancing, none of which the orthodox doctrine considers. Skeptics pointed out all of this throughout the pandemic – and were shouted down as granny-killers.

Alberta

Premier Smith: Canadians support agreement between Alberta and Ottawa and the major economic opportunities it could unlock for the benefit of all

From Energy Now

By Premier Danielle Smith

Get the Latest Canadian Focused Energy News Delivered to You! It’s FREE: Quick Sign-Up Here

If Canada wants to lead global energy security efforts, build out sovereign AI infrastructure, increase funding to social programs and national defence and expand trade to new markets, we must unleash the full potential of our vast natural resources and embrace our role as a global energy superpower.

The Alberta-Ottawa Energy agreement is the first step in accomplishing all of these critical objectives.

Recent polling shows that a majority of Canadians are supportive of this agreement and the major economic opportunities it could unlock for the benefit of all Canadians.

As a nation we must embrace two important realities: First, global demand for oil is increasing and second, Canada needs to generate more revenue to address its fiscal challenges.

Nations around the world — including Korea, Japan, India, Taiwan and China in Asia as well as various European nations — continue to ask for Canadian energy. We are perfectly positioned to meet those needs and lead global energy security efforts.

Our heavy oil is not only abundant, it’s responsibly developed, geopolitically stable and backed by decades of proven supply.

If we want to pay down our debt, increase funding to social programs and meet our NATO defence spending commitments, then we need to generate more revenue. And the best way to do so is to leverage our vast natural resources.

At today’s prices, Alberta’s proven oil and gas reserves represent trillions in value.

It’s not just a number; it’s a generational opportunity for Alberta and Canada to secure prosperity and invest in the future of our communities. But to unlock the full potential of this resource, we need the infrastructure to match our ambition.

There is one nation-building project that stands above all others in its ability to deliver economic benefits to Canada — a new bitumen pipeline to Asian markets.

The energy agreement signed on Nov. 27 includes a clear path to the construction of a one-million-plus barrel-per-day bitumen pipeline, with Indigenous co-ownership, that can ensure our province and country are no longer dependent on just one customer to buy our most valuable resource.

Indigenous co-ownership also provide millions in revenue to communities along the route of the project to the northwest coast, contributing toward long-lasting prosperity for their people.

The agreement also recognizes that we can increase oil and gas production while reducing our emissions.

The removal of the oil and gas emissions cap will allow our energy producers to grow and thrive again and the suspension of the federal net-zero power regulations in Alberta will open to doors to major AI data-centre investment.

It also means that Alberta will be a world leader in the development and implementation of emissions-reduction infrastructure — particularly in carbon capture utilization and storage.

The agreement will see Alberta work together with our federal partners and the Pathways companies to commence and complete the world’s largest carbon capture, utilization and storage infrastructure project.

This would make Alberta heavy oil the lowest intensity barrel on the market and displace millions of barrels of heavier-emitting fuels around the globe.

We’re sending a clear message to investors across the world: Alberta and Canada are leaders, not just in oil and gas, but in the innovation and technologies that are cutting per barrel emissions even as we ramp up production.

Where we are going — and where we intend to go with more frequency — is east, west, north and south, across oceans and around the globe. We have the energy other countries need, and will continue to need, for decades to come.

However, this agreement is just the first step in this journey. There is much hard work ahead of us. Trust must be built and earned in this partnership as we move through the next steps of this process.

But it’s very encouraging that Prime Minister Mark Carney has made it clear he is willing to work with Alberta’s government to accomplish our shared goal of making Canada an energy superpower.

That is something we have not seen from a Canadian prime minister in more than a decade.

Together, in good faith, Alberta and Ottawa have taken the first step towards making Canada a global energy superpower for benefit of all Canadians.

Danielle Smith is the Premier of Alberta

Alberta

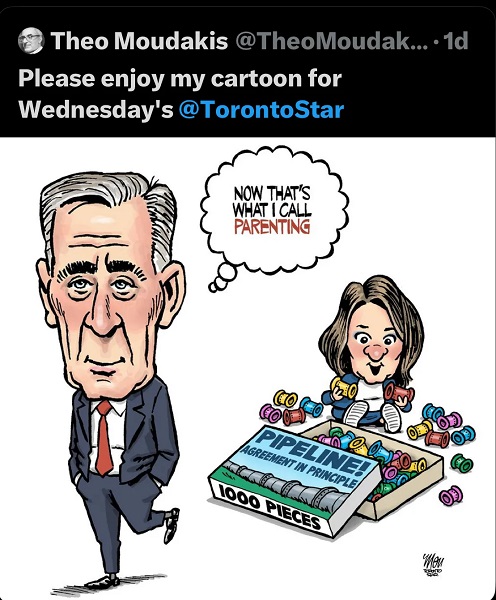

A Memorandum of Understanding that no Canadian can understand

From the Fraser Institute

The federal and Alberta governments recently released their much-anticipated Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) outlining what it will take to build a pipeline from Alberta, through British Columbia, to tidewater to get more of our oil to markets beyond the United States.

This was great news, according to most in the media: “Ottawa-Alberta deal clears hurdles for West Coast pipeline,” was the top headline on the Globe and Mail’s website, “Carney inks new energy deal with Alberta, paving way to new pipeline” according to the National Post.

And the reaction from the political class? Well, former federal environment minister Steven Guilbeault resigned from Prime Minister Carney’s cabinet, perhaps positively indicating that this agreement might actually produce a new pipeline. Jason Kenney, a former Alberta premier and Harper government cabinet minister, congratulated Prime Minister Carney and Premier Smith on an “historic agreement.” Even Alberta NDP Leader Naheed Nenshi called the MOU “a positive step for our energy future.”

Finally, as Prime Minister Carney promised, Canada might build critical infrastructure “at a speed and scale not seen in generations.”

Given this seemingly great news, I eagerly read the six-page Memorandum of Understanding. Then I read it again and again. Each time, my enthusiasm and understanding diminished rapidly. By the fourth reading, the only objective conclusion I could reach was not that a pipeline would finally be built, but rather that only governments could write an MOU that no Canadian could understand.

The MOU is utterly incoherent. Go ahead, read it for yourself online. It’s only six pages. Here are a few examples.

The agreement states that, “Canada and Alberta agree that the approval, commencement and continued construction of the bitumen pipeline is a prerequisite to the Pathways project.” Then on the next line, “Canada and Alberta agree that the Pathways Project is also a prerequisite to the approval, commencement and continued construction of the bitumen pipeline.”

Two things, of course, cannot logically be prerequisites for each other.

But worry not, under the MOU, Alberta and Ottawa will appoint an “Implementation Committee” to deliver “outcomes” (this is from a federal government that just created the “Major Project Office” to get major projects approved and constructed) including “Determining the means by which Alberta can submit its pipeline application to the Major Projects Office on or before July 1, 2026.”

What does “Determining the means” even mean?

What’s worse is that under the MOU, the application for this pipeline project must be “ready to submit to the Major Projects Office on or before July 1, 2026.” Then it could be another two years (or until 2028) before Ottawa approves the pipeline project. But the MOU states the Pathways Project is to be built in stages, starting in 2027. And that takes us back to the circular reasoning of the prerequisites noted above.

Other conditions needed to move forward include:

The private sector must construct and finance the pipeline. Serious question: which private-sector firm would take this risk? And does the Alberta government plan to indemnify the company against these risks?

Indigenous Peoples must co-own the pipeline project.

Alberta must collaborate with B.C. to ensure British Columbians get a cut or “share substantial economic and financial benefits of the proposed pipeline” in MOU speak.

None of this, of course, addresses the major issue in our country—that is, investors lack clarity on timelines and certainty about project approvals. The Carney government established the Major Project Office to fast-track project approvals and provide greater certainty. Of the 11 project “winners” the federal government has already picked, most either already had approvals or are already at an advanced stage in the process. And one of the most important nation-building projects—a pipeline to get our oil to tidewater—hasn’t even been referred to the Major Project Office.

What message does all this send to the investment community? Have we made it easier to get projects approved? No. Have we made things clearer? No. Business investment in Canada has fallen off a cliff and is down 25 per cent per worker since 2014. We’ve seen a massive outflow of capital from the country, more than $388 billion since 2014.

To change this, Canada needs clear rules and certain timelines for project approvals. Not an opaque Memorandum of Understanding.

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoFrom Exception to Routine. Why Canada’s State-Assisted Suicide Regime Demands a Human-Rights Review

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoPower Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoUnceded is uncertain

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoNew Chevy ad celebrates marriage, raising children

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa’s gun ‘buyback’ program will cost billions—and for no good reason

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat’s Going On With Global Affairs Canada and Their $392 Million Spending Trip to Brazil?

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoA Democracy That Can’t Take A Joke Won’t Tolerate Dissent