MacDonald Laurier Institute

Weaponizing human rights tribunals

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By Stéphane Sérafin for Inside Policy

If adopted, Bill C-63 could unleash a wave of “hate speech” complaints that persecute – and prosecute – citizens, businesses, or organizations while stifling online expression.

Much has already been written on Bill C-63, the Trudeau government’s controversial Bill proposing among other things to give the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal jurisdiction to adjudicate “hate speech” complaints arising from comments made on social media. As opponents have noted, the introduction of these new measures presents a significant risk to free expression on many issues that ought to be open to robust public debate.

Proponents, for their part, have tended to downplay these concerns by pointing to the congruence between these new proposed measures and the existing prohibition contained in the Criminal Code. In their view, the fact that the definition of “hate speech” provided by Bill C-63 is identical to that already found in the Criminal Code means that these proposed measures hardly justify the concerns expressed.

This response to critics of Bill C-63 largely misses the point. Certainly, the existing Criminal Code prohibitions on “hate speech” have and continue to raise difficult issues from the standpoint of free expression. However, the real problem with Bill C-63 is not that it adopts the Criminal Code definition, but that it grants the jurisdiction to adjudicate complaints arising under this definition to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

Established in 1977, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal is a federal administrative tribunal based on a model first implemented in Ontario in 1962 and since copied in every other Canadian province and territory. There is a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, just as there is an Ontario Human Rights Tribunal and a British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal, among others. Although these are separate institutions with different jurisdictions, their decisions proceed from similar starting points embedded in nearly identical legislation. In the case of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, that legislation is the Canadian Human Rights Act.

Tribunals such as the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal are administrative bodies, not courts. They are part of the executive branch, alongside the prime minister, Cabinet, and the public service. This has at least three implications for the way the Tribunal is likely to approach the “hate speech” measures that Bill C-63 contemplates. Each of these presents significant risks for freedom of expression that do not arise, or do not arise to the same extent, under the existing Criminal Code provisions.

The first implication is procedural. As an administrative body, the Tribunal is not subject to the same stringent requirements for the presentation of evidence that are used before proper courts, and certainly not subject to the evidentiary standard applied in the criminal law context. But more importantly still, the structure of the Canadian Human Rights Act is one that contemplates a form of hybrid public-private prosecution, in which the decision to bring a complaint falls to a given individual, while its prosecution is taken up by another administrative body, called the Human Rights Commission.

This model differs from both the criminal law context, where both the decision to file charges and prosecute them rest with the Crown, and from the civil litigation context, where the plaintiff decides to bring a claim but must personally bear the cost and effort of doing so. With respect to complaints brought before the Tribunal, it is the complainant who chooses to file a complaint, and the Human Rights Commission that then takes up the burden of proof and the costs of prosecution.

In the context of the existing complaints process, which deals mainly with discriminatory practices in employment and the provision of services, this model is intended to alleviate burdens that might deter individuals from bringing otherwise valid discrimination complaints before the Tribunal. Whatever the actual merits of this approach, however, it presents a very real risk of being weaponized under Bill C-63. Notably, the fact that complainants are not expected to prosecute their own complaints means that there is little to discourage individuals (or activist groups acting through individuals) from filing “hate speech” complaints against anyone expressing opinions with which they disagree.

This feature alone is likely to create a significant chilling effect on online expression. Whether a complaint is ultimately substantiated or not, the model under which the Tribunal operates dispenses complainants from the burden of prosecution but does not dispense defendants from the burden of defending themselves against the complaint in question. Again, this approach may or may not be sensible under existing anti-discrimination measures, which are primarily aimed at businesses with generally greater means. But it becomes obviously one-sided in relation to the “hate speech” measures contemplated by Bill C-63, which instead target anyone engaging in public commentary using online platforms. Anyone who provides public commentary, no matter how measured or nuanced, will thus have to risk personally bearing the cost and effort of defending against a complaint as a condition of online participation. Meanwhile, no such costs exist for those who might want to file complaints.

A second implication arising from the Tribunal’s status as an administrative body with significant implications for Bill C-63 is that its decisions attract “deference” on appeal. By this, I mean that its decisions are given a certain latitude by reviewing courts that appeal courts do not generally give to decisions from lower tribunals, including in criminal matters. “Deference” of this kind is consistent with the broad discretion that legislation confers upon administrative decision-makers such as the Tribunal. However, it also raises significant concerns in relation to Bill C-63 that its proponents have failed to properly address.

In particular, the deference granted to the Tribunal means that proponents of Bill C-63 have been wrong to argue that the congruence between its proposed definition of “hate speech” and existing provisions of the Criminal Code provides sufficient safeguards against threats to freedom of expression.

Deference means that it is possible, and indeed likely, that the Tribunal will develop an interpretation of “hate speech” that diverges significantly from that applied under the Criminal Code. Even if the language used in Bill C-63 is identical to the language found in the Criminal Code, the Tribunal possesses a wide latitude in interpreting what these provisions mean and is not bound by the interpretation that courts give to the Criminal Code. It may even develop an interpretation that is far more draconian than the Criminal Code standard, and reviewing courts are likely to accept that interpretation despite the fact that it diverges from their own.

This problem is exacerbated by the deferential approach that reviewing courts have lately taken towards the application of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to administrative bodies such as the Tribunal. This approach contrasts to the direct application of the Charter that remains characteristic of decisions involving the Criminal Code, including its “hate speech” provisions. It also contrasts with the approach previously applied to provincial Human Rights Tribunal decisions dealing with the distribution of print publications that were found to amount to “hate speech” under provincial human rights laws. Decisions such as these have frequently been criticized for not taking sufficiently seriously the Charter right to freedom of expression. However, they at least involve a direct application of the Charter, including a requirement that the government justify any infringement of the Charter right to free expression as a reasonable limit in a “free and democratic society.”

Under the approach now favoured by Canadian courts, these same courts now extend the deference paradigm to administrative decision-makers, such as the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, even where the Charter is potentially engaged. In practice, this means that instead of asking whether a rights infringement is justified in a “free and democratic society,” courts ask whether administrative-decision makers have properly “balanced” even explicitly enumerated Charter rights such as the right to freedom of expression against competing “Charter values” whenever a particular administrative decision is challenged.

This approach to Charter-compliance has led to a number of highly questionable decisions in which the Charter rights at issue have at best been treated as a secondary concern. Notably, it led the Supreme Court of Canada to affirm the denial of the accreditation of a new law school at a Christian university in British Columbia, on the basis that this university imposed a covenant on students requiring them to not engage in extra-marital sexual relations that was deemed discriminatory against non-heterosexual students. Four of the nine Supreme Court of Canada judges would have applied a similar approach to uphold a finding by the Quebec Human Rights Tribunal that a Quebec comedian had engaged in discriminatory conduct because of a routine in which he made jokes at the expense of a disabled child who had cultivated a public image. (With recent changes to the composition of the court, that minority would now likely be a majority). This approach to Charter-compliance only increases the likelihood that the proposed online hate speech provisions will develop in a manner that is different from, and more repressive than, the existing Criminal Code standard.

Finally, the third and potentially most consequential difference to arise from the Tribunal’s status as an administrative rather than judicial body concerns the remedies that the Tribunal can order if a particular complaint is substantiated. Notably, the monetary awards that the Tribunal can impose – currently capped at $20,000 – are often imposed on the basis of standards that are more flexible than those applicable to civil claims brought before judicial bodies. An equivalent monetary remedy is contemplated for the new online “hate speech” provisions. This remedy is in addition to the possibility, also currently contemplated by Bill C-63, of ordering a defendant to pay a non-compensatory penalty (in effect, a fine payable to the complainant, rather than the state) of up to $50,000. This last remedy especially adds to the incentives created by the Commission model for individuals (and activist groups) to file complaints wherever possible.

That said, the monetary remedies contemplated by Bill C-63 are perhaps not the most concerning remedies as far as freedom of expression is concerned. Bill C-63 also provides the Tribunal with the power to issue “an order to cease the discriminatory practice and take measures, in consultation with the Commission on the general purposes of the measures, to redress the practice or to prevent the same or a similar practice from recurring.” This remedy brings to mind the Tribunal’s existing power to under the anti-discrimination provisions of the Canadian Human Rights Act.

It is not entirely clear how this kind of directed remedy will be applied in the context of Bill C-63. The Bill provides for a number of exemptions to the application of the new “hate speech” measures, most notably to social media platforms, which may limit their scope of application to some extent. Nonetheless, it is not inconceivable that remedies might be sought against other kinds of online content distributors in an effort to have them engage in proactive censorship or otherwise set general policy with little or no democratic oversight. This possibility is certainly heightened by the way in which the existing directed remedies for anti-discrimination have been used to date.

A prominent example of directed remedies being implemented in a way that circumvents democratic oversight is provided by the Canada Research Chairs (“CRC”) program endowed by the federal government at various Canadian universities. That program has recently come under scrutiny due to the on appointments under the CRC program. In reality, those implementing the quotas are merely proceeding in accordance with a settlement agreement entered into by the federal government following a complaint made by individuals alleging discrimination in CRC appointments. That complaint was brought before the Tribunal and sought precisely the kind of redress to which the government eventually consented.

Whatever the merits of the settlement reached in the CRC case, the results achieved by the complainants through their complaint to the Tribunal were far more politically consequential than the kinds of monetary awards that have been the focus of most discussion in the Bill C-63 context. As with the one-sidedness of the procedural incentives to file complaints and the deference that courts show to Tribunal decisions, the true scope of the Tribunal’s remedial jurisdiction presents significant risks to freedom of expression that simply have no equivalent under the Criminal Code. These issues must be kept in mind when addressing the content of that Bill, which in its current form risks being weaponized by politically motivated individuals and activist groups to stifle online expression with little to no democratic oversight.

Stéphane Sérafin is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and assistant professor in the Common Law Section of the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa. He holds a Bachelor of Social Science, Juris Doctor, and Licentiate in Law from the University of Ottawa and completed his Master of Laws at the University of Toronto. He is a member of the Law Society of Ontario and the Barreau du Québec.

Business

Canada must address its birth tourism problem

By Sergio R. Karas for Inside Policy

One of the most effective solutions would be to amend the Citizenship Act, making automatic citizenship conditional upon at least one parent being a Canadian citizen or permanent resident.

Amid rising concerns about the prevalence of birth tourism, many Western democracies are taking steps to curb the practice. Canada should take note and reconsider its own policies in this area.

Birth tourism occurs when pregnant women travel to a country that grants automatic citizenship to all individuals born on its soil. There is increasing concern that birthright citizenship is being abused by actors linked to authoritarian regimes, who use the child’s citizenship as an anchor or escape route if the conditions in their country deteriorate.

Canada grants automatic citizenship by birth, subject to very few exceptions, such as when a child is born to foreign diplomats, consular officials, or international representatives. The principle known as jus soli in Latin for “right of the soil” is enshrined in Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act.

Unlike many other developed countries, Canada’s legislation does not consider the immigration or residency status of the parents for the child to be a citizen. Individuals who are in Canada illegally or have had refugee claims rejected may be taking advantage of birthright citizenship to delay their deportation. For example, consider the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling in Baker v. Canada. The court held that the deportation decision for a Jamaican woman – who did not have legal status in Canada but had Canadian-born children – must consider the best interests of the Canadian-born children.

There is mounting evidence of organized birth tourism among individuals from the People’s Republic of China, particularly in British Columbia. According to a January 29 news report in Business in Vancouver, an estimated 22–23 per cent of births at Richmond Hospital in 2019–20 were to non-resident mothers, and the majority were Chinese nationals. The expectant mothers often utilize “baby houses” and maternity packages, which provide private residences and a comprehensive bundle of services to facilitate the mother’s experience, so that their Canadian-born child can benefit from free education and social and health services, and even sponsor their parents for immigration to Canada in the future. The financial and logistical infrastructure supporting this practice has grown, with reports of dozens of birth houses in British Columbia catering to a Chinese clientele.

Unconditional birthright citizenship has attracted expectant mothers from countries including Nigeria and India. Many arrive on tourist visas to give birth in Canada. The number of babies born in Canada to non-resident mothers – a metric often used to measure birth tourism – dropped sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic but has quickly rebounded since. A December 2023 report in Policy Options found that non-resident births constituted about 1.6 per cent of all 2019 births in Canada. That number fell to 0.7 per cent in 2020–2021 due to travel restrictions, but by 2022 it rebounded to one per cent of total births. That year, there were 3,575 births to non-residents – 53 per cent more than during the pandemic. Experts believe that about half of these were from women who travelled to Canada specifically for the purpose of giving birth. According to the report, about 50 per cent of non-resident births are estimated to be the result of birth tourism. The upward trend continued into 2023–24, with 5,219 non-resident births across Canada.

Some hospitals have seen more of these cases than others. For example, B.C.’s Richmond Hospital had 24 per cent of its births from non-residents in 2019–20, but that dropped to just 4 per cent by 2022. In contrast, Toronto’s Humber River Hospital and Montreal’s St. Mary’s Hospital had the highest rates in 2022–23, with 10.5 per cent and 9.4 per cent of births from non-residents, respectively.

Several developed countries have moved away from unconditional birthright citizenship in recent years, implementing more restrictive measures to prevent exploitation of their immigration systems. In the United Kingdom, the British Nationality Act abolished jus soli in its unconditional form. Now, a child born in the UK is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is a British citizen or has settled status. This change was introduced to prevent misuse of the immigration and nationality framework. Similarly, Germany follows a conditional form of jus soli. According to its Nationality Act, a child born in Germany acquires citizenship only if at least one parent has legally resided in the country for a minimum of eight years and holds a permanent residence permit. Australia also eliminated automatic birthright citizenship. Under the Australian Citizenship Act, a child born on Australian soil is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is an Australian citizen or permanent resident. Alternatively, if the child lives in Australia continuously for ten years, they may become eligible for citizenship through residency. These policies illustrate a global trend toward limiting automatic citizenship by birth to discourage birth tourism.

In the United States, Section 1 of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution prescribes that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The Trump administration has launched a policy and legal challenge to the longstanding interpretation that every person born in the US is automatically a citizen. It argues that the current interpretation incentivizes illegal immigration and results in widespread abuse of the system.

On January 20, 2025, President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 14156: Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship, aimed at ending birthright citizenship for children of undocumented migrants and those with lawful but temporary status in the United States. The executive order stated that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause “rightly repudiated” the Supreme Court’s “shameful decision” in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, which dealt with the denial of citizenship to black former slaves. The administration argues that the Fourteenth Amendment “has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to anyone born within the United States.” The executive order claims that the Fourteenth Amendment has “always excluded from birthright citizenship persons who were born in the United States but not subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The order outlines two categories of individuals that it claims are not subject to United States jurisdiction and thus not automatically entitled to citizenship: a child of an undocumented mother and father who are not citizens or lawful permanent residents; and a child of a mother who is a temporary visitor and of a father who is not a citizen or lawful permanent resident. The executive order attempts to make ancestry a criterion for automatic citizenship. It requires children born on US soil to have at least one parent who has US citizenship or lawful permanent residency.

On June 27, 2025, the US Supreme Court in Trump v. CASA, Inc. held that lower federal courts exceed their constitutional authority when issuing broad, nationwide injunctions to prevent the Trump administration from enforcing the executive order. Such relief should be limited to the specific plaintiffs involved in the case. The Court did not address whether the order is constitutional, and that will be decided in the future. However, this decision removes a major legal obstacle, allowing the administration to enforce the policy in areas not covered by narrower injunctions. Since the order could affect over 150,000 newborns each year, future decisions on the merits of the order are still an especially important legal and social issue.

In addition to the executive order, the Ban Birth Tourism Act – introduced in the United States Congress in May 2025 – aims to prevent women from entering the country on visitor visas solely to give birth, citing an annual 33,000 births to tourist mothers. Simultaneously, the State Department instructed US consulates abroad to deny visas to applicants suspected of “birth tourism,” reinforcing a sharp policy pivot.

In light of these developments, Canada should be wary. It may see an increase in birth tourism as expectant mothers look for alternative destinations where their children can acquire citizenship by birth.

Canadian immigration law does not prevent women from entering the country on a visitor visa to give birth. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the associated regulations do not include any provisions that allow immigration officials or Canada Border Services officers to deny visas or entry based on pregnancy. Section 22 of the IRPA, which deals with temporary residents, could be amended. However, making changes to regulations or policy would be difficult and could lead to inconsistent decisions and a flurry of litigation. For example, adding questions about pregnancy to visa application forms or allowing officers to request pregnancy tests in certain high-risk cases could result in legal challenges on the grounds of privacy and discrimination.

In a 2019 Angus Reid Institute survey, 64 per cent of Canadians said they would support changing the law to stop granting citizenship to babies born in Canada to parents who are only on tourist visas. One of the most effective solutions would be to amend Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act, making it mandatory that at least one parent be a Canadian citizen or permanent resident for a child born in Canada to automatically receive citizenship. Such a model would align with citizenship legislation in countries like the UK, Germany, and Australia, where jus soli is conditional on parental status. Making this change would close the current loophole that allows birth tourism, without placing additional pressure on visa officers or requiring new restrictions on tourist visas. It would retain Canada’s inclusive citizenship framework while aligning with practices in other democratic nations.

Canada currently lacks a proper and consistent system for collecting data on non-resident births. This gap poses challenges in understanding the scale and impact of birth tourism. Since health care is under provincial jurisdiction, the responsibility for tracking and managing such data falls primarily on the provinces. However, there is no national framework or requirement for provinces or hospitals to report the number of births by non-residents, leading to fragmented and incomplete information across the country. One notable example is BC’s Richmond Hospital, which has become a well-known birth tourism destination. In the 2017–18 fiscal year alone, 22 per cent of all births at Richmond Hospital were to non-resident mothers. These births generated approximately $6.2 million in maternity fees, out of which $1.1 million remained unpaid. This example highlights not only the prevalence of the practice but also the financial burden it places on the provincial health care programs. To better address the issue, provinces should implement more robust data collection practices. Information should include the mother’s residency or visa status, the total cost of care provided, payment outcomes (including outstanding balances), and any necessary medical follow-ups.

Reliable and transparent data is essential for policymakers to accurately assess the scope of birth tourism and develop effective responses. Provinces should strengthen data collection practices and consider introducing policies that require security deposits or proof of adequate medical insurance coverage for expectant mothers who are not covered by provincial healthcare plans.

Canada does not currently record the immigration or residency status of parents on birth certificates, making it difficult to determine how many children are born to non-resident or temporary resident parents. Including this information at the time of birth registration would significantly improve data accuracy and support more informed policy decisions. By improving data collection, increasing transparency, and adopting preventive financial safeguards, provinces can more effectively manage the challenges posed by birth tourism, and the federal government can implement legislative reforms to deal with the problem.

Sergio R. Karas, principal of Karas Immigration Law Professional Corporation, is a certified specialist in Canadian citizenship and immigration law by the Law Society of Ontario. He is co-chair of the ABA International Law Section Immigration and Naturalization Committee, past chair of the Ontario Bar Association Citizenship and Immigration Section, past chair of the International Bar Association Immigration and Nationality Committee, and a fellow of the American Bar Foundation. He can be reached at [email protected]. The author is grateful for the contribution to this article by Jhanvi Katariya, student-at-law.

Alberta

‘Far too serious for such uninformed, careless journalism’: Complaint filed against Globe and Mail article challenging Alberta’s gender surgery law

Macdonald Laurier Institute challenges Globe article on gender medicine

The complaint, now endorsed by 41 physicians, was filed in response to an article about Alberta’s law restricting gender surgery and hormones for minors.

On June 9, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute submitted a formal complaint to The Globe and Mail regarding its May 29 Morning Update by Danielle Groen, which reported on the Canadian Medical Association’s legal challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26.

Written by MLI Senior Fellow Mia Hughes and signed by 34 Canadian medical professionals at the time of submission to the Globe, the complaint stated that the Morning Update was misleading, ideologically slanted, and in violation the Globe’s own editorial standards of accuracy, fairness, and balance. It objected to the article’s repetition of discredited claims—that puberty blockers are reversible, that they “buy time to think,” and that denying access could lead to suicide—all assertions that have been thoroughly debunked in recent years.

Given the article’s reliance on the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the complaint detailed the collapse of WPATH’s credibility, citing unsealed discovery documents from an Alabama court case and the Cass Review’s conclusion that WPATH’s guidelines—and those based on them—lack developmental rigour. It also noted the newsletter’s failure to mention the growing international shift away from paediatric medical transition in countries such as the UK, Sweden, and Finland. MLI called for the article to be corrected and urged the Globe to uphold its commitment to balanced, evidence-based journalism on this critical issue.

On June 18, Globe and Mail Standards Editor Sandra Martin responded, defending the article as a brief summary that provided a variety of links to offer further context. However, the three Globe and Mail news stories linked to in the article likewise lacked the necessary balance and context. Martin also pointed to a Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) statement linked to in the newsletter. She argued it provided “sufficient context and qualification”—despite the fact that the CPS itself relies on WPATH’s discredited guidelines. Notwithstanding, Martin claimed the article met editorial standards and that brevity justified the lack of balance.

MLI responded that brevity does not excuse misinformation, particularly on a matter as serious as paediatric medical care, and reiterated the need for the Globe to address the scientific inaccuracies directly. MLI again called for the article to be corrected and for the unsupported suicide claim to be removed. As of this writing, the Globe has not responded.

Letter of complaint

June 9, 2025

To: The Globe and Mail

Attn: Sandra Martin, standards editor

CC: Caroline Alphonso, health editor; Mark Iype, deputy national editor and Alberta bureau chief

To the editors;

Your May 29 Morning Update: The Politics of Care by Danielle Groen, covering the Canadian Medical Association’s legal challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26, was misleading and ideologically slanted. It is journalistically irresponsible to report on contested medical claims as undisputed fact.

This issue is far too serious for such uninformed, careless journalism lacking vital perspectives and scientific context. At stake is the health and future of vulnerable children, and your reporting risks misleading parents into consenting to irreversible interventions based on misinformation.

According to The Globe and Mail’s own Journalistic Principles outlined in its Editorial Code of Conduct, the credibility of your reporting rests on “solid research, clear, intelligent writing, and maintaining a reputation for honesty, accuracy, fairness, balance and transparency.” Moreover, your principles go on to state that The Globe will “seek to provide reasonable accounts of competing views in any controversy.” The May 29 update violated these principles. There is, as I will show, a widely available body of scientific information that directly contests the claims and perspectives presented in your article. Yet this information is completely absent from your reporting.

The collapse of WPATH’s credibility

The article’s claim that Alberta’s law “falls well outside established medical practice” and could pose the “greatest threat” to transgender youth is both false and inflammatory. There is no global medical consensus on how to treat gender-distressed young people. In fact, in North America, guidelines are based on the Standards of Care developed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)—an organization now indisputably shown to place ideology above evidence.

For example, in a U.S. legal case over Alabama’s youth transition ban, WPATH was forced to disclose over two million internal emails. These revealed the organization commissioned independent evidence reviews for its latest Standards of Care (SOC8)—then suppressed those reviews when they found overwhelmingly low-quality evidence. Yet WPATH proceeded to publish the SOC8 as if it were evidence-based. This is not science. It is fraudulent and unethical conduct.

These emails also showed Admiral Rachel Levine—then-assistant secretary for Health in the Biden administration—pressured WPATH to remove all lower age recommendations from the guidelines—not on scientific grounds, but to avoid undermining ongoing legal cases at the state level. This is politics, not sound medical practice.

The U.K.’s Cass Review, a major multi-year investigation, included a systematic review of the guidelines in gender medicine. A systematic review is considered the gold standard because it assesses and synthesizes all the available research in a field, thereby reducing bias and providing a large comprehensive set of data upon which to reach findings. The systematic review of gender medicine guidelines concluded that WPATH’s standards of care “lack developmental rigour” and should not be used as a basis for clinical practice. The Cass Review also exposed citation laundering where medical associations endlessly recycled weak evidence across interlocking guidelines to fabricate a false consensus. This led Cass to suggest that “the circularity of this approach may explain why there has been an apparent consensus on key areas of practice despite the evidence being poor.”

Countries like Sweden, Finland, and the U.K. have now abandoned WPATH and limited or halted medicalized youth transitions in favour of a therapy-first approach. In Norway, UKOM, an independent government health agency, has made similar recommendations. This shows the direction of global practice is moving away from WPATH’s medicalized approach—not toward it. As part of any serious effort to “provide reasonable accounts of competing views,” your reporting should acknowledge these developments.

Any journalist who cites WPATH as a credible authority on paediatric gender medicine—especially in the absence of contextualizing or competing views—signals a lack of due diligence and a fundamental misunderstanding of the field. It demonstrates that either no independent research was undertaken, or it was ignored despite your editorial standards.

Puberty blockers don’t ‘buy time’ and are not reversible

Your article repeats a widely debunked claim: that puberty blockers are a harmless pause to allow young people time to explore their identity. In fact, studies have consistently shown that between 98 per cent and 100 per cent of children placed on puberty blockers go on to take cross-sex hormones. Before puberty blockers, most children desisted and reconciled with their birth sex during or after puberty. Now, virtually none do.

This strongly suggests that blocking puberty in fact prevents the natural resolution of gender distress. Therefore, the most accurate and up-to-date understanding is that puberty blockers function not as a pause, but as the first step in a treatment continuum involving irreversible cross-sex hormones. Indeed, a 2022 paper found that while puberty suppression had been “justified by claims that it was reversible … these claims are increasingly implausible.” Again, adherence to the Globe’s own editorial guidelines would require, at minimum, the acknowledgement of the above findings alongside the claims your May 29 article makes.

Moreover, it is categorically false to describe puberty blockers as “completely reversible.” Besides locking youth into a pathway of further medicalization, puberty blockers pose serious physical risks: loss of bone density, impaired sexual development, stunted fertility, and psychosocial harm from being developmentally out of sync with peers. There are no long-term safety studies. These drugs are being prescribed to children despite glaring gaps in our understanding of their long-term effects.

Given the Globe’s stated editorial commitment to principles such as “accuracy,” the crucial information from the studies linked above should be provided in any article discussing puberty blockers. At a bare minimum, in adherence to the Globe’s commitment to “balance,” this information should be included alongside the contentious and disputed claims the article makes that these treatments are reversible.

No proof of suicide prevention

The most irresponsible and dangerous claim in your article is that denying access to puberty blockers could lead to “depression, self-harm and suicide.” There is no robust evidence supporting this transition-or-suicide narrative, and in fact, the findings of the highest-quality study conducted to date found no evidence that puberty suppression reduces suicide risk.

Suicide is complex and attributing it to a single cause is not only false—it violates all established suicide reporting guidelines. Sensationalized claims like this risk creating contagion effects and fuelling panic. In the public interest, reporting on the topic of suicide must be held to the most rigorous standards, and provide the most high-quality and accurate information.

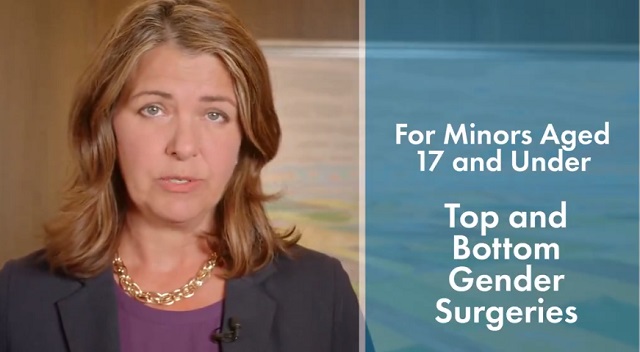

Euphemism hides medical harm

Your use of euphemistic language obscures the extreme nature of the medical interventions being performed in gender clinics. Calling double mastectomies for teenage girls “paediatric breast surgeries for gender-affirming reasons” sanitizes the medically unnecessary removal of a child’s healthy organs. Referring to phalloplasty and vaginoplasty as “gender-affirming surgeries on lower body parts” conceals the fact that these are extreme operations involving permanent disfigurement, high complication rates, and often requiring multiple revisions.

Honest journalism should not hide these facts behind comforting language. Your reporting denies youth, their parents, and the general public the necessary information to understand the nature of these interventions. Members of the general public rely greatly on the news media to equip them with such information, and your own editorial standards claim you will fulfill this core responsibility.

Your responsibility to the public

As a flagship Canadian news outlet, your responsibility is not to amplify activist messaging, but to report the truth with integrity. On a subject as medically and ethically fraught as paediatric gender medicine, accuracy is not optional. The public depends on you to scrutinize claims, not echo ideology. Parents may make irreversible decisions on behalf of their children based on the narratives you promote. When reporting is false or ideologically distorted, the cost is measured in real-world harm to some of our society’s most vulnerable young people.

I encourage the Globe and Mail to publish an updated version on this article in order to correct the public record with the relevant information discussed above, and to modify your reporting practices on this matter going forward—by meeting your own journalistic standards—so that the public receives balanced, correct, and reliable information on this vital topic.

Trustworthy journalism is a cornerstone of public health—and on the issue of paediatric gender medicine, the stakes could not be higher.

Sincerely,

Mia Hughes

Senior Fellow, Macdonald-Laurier Institute

Author of The WPATH Files

The following 41 physicians have signed to endorse this letter:

Dr. Mike Ackermann, MD

Dr. Duncan Veasey, Psy MD

Dr. Rick Gibson, MD

Dr. Benjamin Turner, MD, FRCSC

Dr. J.N. Mahy, MD, FRCSC, FACS

Dr. Khai T. Phan, MD, CCFP

Dr. Martha Fulford, MD

Dr. J. Edward Les, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Darrell Palmer, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Jane Cassie, MD, FRCPC

Dr. David Lowen, MD, FCFP

Dr. Shawn Whatley, MD, FCFP (EM)

Dr. David Zitner, MD

Dr. Leonora Regenstreif, MD, CCFP(AM), FCFP

Dr. Gregory Chan, MD

Dr. Alanna Fitzpatrick, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Chris Millburn, MD, CCFP

Dr. Julie Curwin, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Roy Eappen, MD, MDCM, FRCP (c)

Dr. York N. Hsiang, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Dion Davidson, MD, FRCSC, FACS

Dr. Kevin Sclater, MD, CCFP (PC)

Dr. Theresa Szezepaniak, MB, ChB, DRCOG

Dr. Sofia Bayfield, MD, CCFP

Dr. Elizabeth Henry, MD, CCFP

Dr. Stephen Malthouse, MD

Dr. Darrell Hamm, MD, CCFP

Dr. Dale Classen, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Adam T. Gorner, MD, CCFP

Dr. Wesley B. Steed, MD

Dr. Timothy Ehmann, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Ryan Torrie, MD

Dr. Zachary Heinricks, MD, CCFP

Dr. Jessica Shintani, MD, CCFP

Dr. Mark D’Souza, MD, CCFP(EM), FCFP*

Dr. Joanne Sinai, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. Jane Batt, MD*

Dr. Brent McGrath, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. Leslie MacMillan MD FRCPC (emeritus)*

Dr. Ian Mitchell, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. John Cunnington, MD

*Indicates physician who signed following the letter’s June 9 submission to the Globe and Mail, but in advance of this letter being published on the MLI website.

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoCanada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoCharity Campaigns vs. Charity Donations

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

-

Red Deer1 day ago

Red Deer1 day agoWesterner Days Attraction pass and New Experiences!